By way of an opening, in 1957 a pink lady in a pink dress with her hair in a period updo walks into a pink room with pretty pink curtains and wallpaper and a few fancy pink chairs and cushions scattered around an art deco fireplace. “Hmm…” she muses. “Now why did I come in here again?”

It takes a second of brainwork to read the pink lady whose distracted murmur opens Richard McGuire’s magnum opus Here as a stand-in for the author himself, a sober fellow staring piercingly out from the back flap of the book jacket, but there’s no denying the line fits. Here’s moment of conception was 25 years ago, when the germ of this book appeared as six pages in an issue of Francoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman’s RAW anthology before undergoing a gestation period long enough to bring thirteen elephants to term and finally coming fully formed as an understated, novel-sized Pantheon hardcover. Given the wealth of art both in and outside the comics medium that McGuire’s dished up between the two incarnations of Here, it’s impossible to imagine that he spent all of that twenty-five-year stretch working on this book (though it does weigh in at a seriously impressive 304 pages), so one can imagine the pink lady’s sentiments were the author’s own at some point during the book’s creation. Why bother to dress up a decades-old anthology short in the sequined bookstore drag of a “graphic novel?"

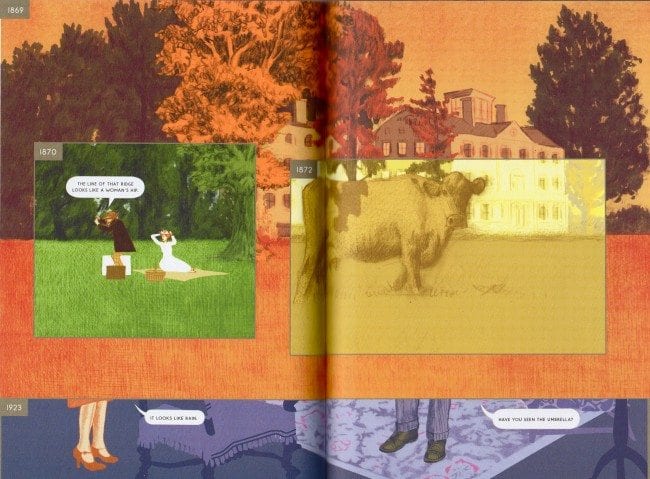

Of course, the answer is that the original “Here” is no ordinary decades-old anthology short, but one that belongs with Krigstein’s “Master Race” and Moriarty’s “Jack Survives” pieces in the, uh, pantheon of comics short stories that managed to move the needle of the art form in a specific direction. The conceit of “Here”, which is carried over to Here, is a simple, ruthlessly effective one: every panel of the story depicts the exact same piece of land, while undergoing wild jumps forward and back in time, transforming a suburban New Jersey living room into a pastoral meadow into a stegosaurus’s stomping grounds and back again, using the potentialities of comics to elide and rebuild thousands of years of historical development in a few pen lines. Not content to stop here, McGuire opens up smaller panels within his panels, little insets showing how a cat in 1999 will pace the selfsame floorboards trod by New Year’s revelers in 1940. There’s not a lot more to the original “Here” than that: the exhibition of a neat new formal trick to be used in comics and a musing on history and the concreteness of what we view as the unimpeachable present. Chris Ware, among other luminaries, was flabbergasted, and the impassioned talking-up of “Here” that occurred subsequent to its original appearance gave it quite the reputation in art comics circles.

For my part, I never really rated the original “Here”, having seen it alongside the more advanced work that Ware, along with Frank Quitely and Olivier Schrauwen (among others) produced after being shown the way by McGuire’s example. For me, anyway, “Here” the anthology short belongs with things like “A Trip to the Moon” and Naked Lunch - formally audacious, narratively light works of serious historical import that were inevitably superseded as the new ideas they brought to the table were absorbed into the mainstream. So when I learned a few years ago that Here the book was in the offing, I was pretty skeptical. It sounded like a cash-in, or maybe a failure of imagination - 300 pages of that old thing? Especially given that McGuire had made far more interesting work since 1989, it seemed a waste, so I wrote it off.

It took one look at a single spread from the new book to convince me I might have made a mistake - in the past twenty-five years, McGuire’s presentation of his concept has managed to expand as much as the comics form itself has. Where the original “Here” suffers from the young McGuire’s uncertain figuration, the new book sets down each human (and animal) form with the casual certainty of a veteran illustrator. Where the original’s black and white printing pushes the reader back, reducing one’s participation in the story to remote appreciation, the new book is alive with a veritable encyclopedia of beautifully considered color schemes designed to draw the eye into the pictures, leaving the world outside its pages behind. Where the rigid six-panel grid of the original has a claustrophobic, staccato feel no matter what size it’s printed (especially once McGuire starts in with the insets), the new book splashes each “master” image across a whole double-page spread, allowing juxtaposed windows into different times to breathe and roll into one another, like nouns in a line of poetry. All the space is necessary -- from the start, Here the book has the cast of an epic about it, and an epic is exactly what McGuire delivers.

Chronologically, this is what happens in Here. Life inches forth from the neon nothingness of the planet’s surface circa 3 billion BCE. Dinosaurs are followed by prehistoric mammals in sporadic wanderings past the stationary camera McGuire has set down on his little piece of earth. Ice ages come and go. Bodies of water form, dry up, reappear. Entirely different phyla of plant life take root, flourish, and are replaced. 1352 AD sees the first appearance of humanity, as a beautiful Indian maiden dives silently into a pool and slips quickly out of sight. A Lenni Lenape tribe takes up residence in what has become a thick forest. A few centuries later Dutch explorers appear. Ben Franklin’s kinfolk clear some trees and build a palatial estate, which burns to the ground some years later. Farms, then a town slowly spring up. In 1907, a house is built surrounding McGuire’s vantage point, and successive generations live out their lives in it. (Our viewpoint is placed in the living room, so we see a lot of socializing, some playing, some relaxing, a little sleeping, and no eating or sex.) A hundred years from now, rising tides break through the windows, and for silent decades water closes over the little patch of land we are observing. In the 23rd century the house’s former site has become a stop on a computer-guided tour of the wetlands that used to be a city, and in the 24th century some kind of nuclear disaster seems to have occurred. In a glimpse of the year 22,175, a few hummingbirds, a fish, and some kind of Loch Ness Monster/horse hybrid thing are seemingly having a pretty dope time among tropical plants and beautiful flowers. And that’s it, though of course it isn’t. The plot is everything. The characters are everyone. The marvel of Here is how many times the tiny moments McGuire captures in a single panel, at most two or three, manage to put across the familiar, the hilarious, the emotionally wrenching, or the beautifully strange unknown; and how they all blend with one another across the decades and centuries he has placed between them. It’s a game of Chinese whispers constructed with the elegance of a bottled ship.

Chronologically, this is what happens in Here. Life inches forth from the neon nothingness of the planet’s surface circa 3 billion BCE. Dinosaurs are followed by prehistoric mammals in sporadic wanderings past the stationary camera McGuire has set down on his little piece of earth. Ice ages come and go. Bodies of water form, dry up, reappear. Entirely different phyla of plant life take root, flourish, and are replaced. 1352 AD sees the first appearance of humanity, as a beautiful Indian maiden dives silently into a pool and slips quickly out of sight. A Lenni Lenape tribe takes up residence in what has become a thick forest. A few centuries later Dutch explorers appear. Ben Franklin’s kinfolk clear some trees and build a palatial estate, which burns to the ground some years later. Farms, then a town slowly spring up. In 1907, a house is built surrounding McGuire’s vantage point, and successive generations live out their lives in it. (Our viewpoint is placed in the living room, so we see a lot of socializing, some playing, some relaxing, a little sleeping, and no eating or sex.) A hundred years from now, rising tides break through the windows, and for silent decades water closes over the little patch of land we are observing. In the 23rd century the house’s former site has become a stop on a computer-guided tour of the wetlands that used to be a city, and in the 24th century some kind of nuclear disaster seems to have occurred. In a glimpse of the year 22,175, a few hummingbirds, a fish, and some kind of Loch Ness Monster/horse hybrid thing are seemingly having a pretty dope time among tropical plants and beautiful flowers. And that’s it, though of course it isn’t. The plot is everything. The characters are everyone. The marvel of Here is how many times the tiny moments McGuire captures in a single panel, at most two or three, manage to put across the familiar, the hilarious, the emotionally wrenching, or the beautifully strange unknown; and how they all blend with one another across the decades and centuries he has placed between them. It’s a game of Chinese whispers constructed with the elegance of a bottled ship.

McGuire obviously has no qualms about loading up his readers’ plates, especially in a book that begs to be knocked back in a single sitting. I tend to think of it as a comics truism that the shorter way is always, always the best way to tell a story, but maybe Here, six pages that became hundreds, is the exception that proves the rule. By patiently teasing out a more or less complete historical and poetic context for the patch of land he sets his story down on, returning to characters and scenes again and again while simultaneously showing us the circumstances that brought them forth, McGuire transcends the quick, “gotcha!” feel of the original short and turns a formal exercise into something as rich with character and anecdote and forward motion as any more traditional novel. The amount of ground he manages to satisfyingly cover is immense: films like Samsara or Koyaanisqatsi have a comparable reach, but are forced to restrict themselves to what can be captured on tape in the here and now, while the generational sagas of the great Russian novelists seem rather anthropocentric in comparison to Here. So combine those two things with a heaping stack of beautiful visual art and you’ve got the triple triumph contained in McGuire’s book: a gorgeously realized, documentary-style chronicle of a million millennia, condensed into a little book and put together not as educational material, but for maximum poetic and dramatic effect.

It’s hard to think of another comic that’s taken aim this high, let alone one that’s been so successful in doing so. In large part, that success is because the maximalist tendencies of Here are matched by an equally powerful sense of restraint. McGuire spends over 300 pages exploring one formal technique, one property exclusive to comics, and comes away with something as specific to the medium, as unachievable anywhere else, as any other artist has managed to. Contrast this with the last two big Great American Graphic Novel-y books Pantheon put out, Asterios Polyp and Building Stories. In their books Mazzucchelli and Ware, so intent on showing off the potential of the comics medium as they’ve imagined it, throw everything but the kitchen sink at the reader in dizzying, virtuoso displays of talent and craft that only obfuscate (maybe even downright contradict) the humble, quotidian stories they’re trying so desperately to impress us with.

With the example of Here as contrast, that approach just seems way too much by comparison, like a Frank Capra movie scored with unceasing Wagner (or Skrillex). McGuire earns his book’s epic status with its content, not formal razzle dazzle; despite being experimentally audacious enough for ten comics, it’s so readable and obvious that anyone who understands the concept of numbered years can jump right in and go without pausing. Thanks to the easy readability McGuire establishes, this book is a page turner without being a potboiler. No protracted melodramas occur between the cosmic whirl of Here’s panels, no heartbreak or gunfights or family betrayal.

Still, like every comic, Here must live or die on the strength of its art, and McGuire acquits himself every bit as strongly with his visuals as he does with his story. If the book is more a compendium of events than a single narrative, it is also more a compendium of artistic approaches than a vehicle for any single one. Some of this is no doubt due to the assistance of Min Choi, Maelle Doliveux, and Keren Katz, credited on the book’s final page as “Team Here” - but with or without other cooks in the kitchen, McGuire’s ability to differentiate time and substance with different artistic media is hugely impressive. Scenes of cold or watery landscapes are often indicated with a few smears of watercolor, while the interior shots of the home are made up of solid blocks of digital color, with the organic forms of the people living there indicated by scratchy colored pencil lines. Some forms are demarcated with a smoothly rigid precision, as easily pieced together as a children’s puzzle, while other seem to shimmer and vibrate with the evidence of the human hand behind them. But most noticeable, and impressive, are the colors. McGuire pitches each individual image (of which there are a dizzying number) with a color scheme all its own, an overriding flavor that is then mixed into the whole of the book with the precision and foresight of a master chef engaged in preparing a multi-course meal. Each page’s colorway is distinct from the last but feels unmistakably of a piece, whether it’s a muted pastel accumulation of the kind we’re used to seeing from Chris Ware or a starkly Impressionist vista straight out of Kokoschka. Color more than any other tool available to the cartoonist has the ability to reach out and touch the audience on the arm, to communicate not just a specific place but a specific feeling, the reasoning behind the pictures -- and with a facility that borders on the telepathic, McGuire’s colors place us again and again within whatever bubble his story dictates we find ourselves in, whether the curry-yellow mid-1970s or the ice-blue ice age or the alpine green of a pre-Columbian spring.

And yet describing the art, even after describing the story, doesn’t get you much closer to the substance of the thing, because Here (whether in print or ebook form) more than pretty much anything else I’ve ever read constructs itself as a comic, making its points with compositions and transitions and juxtapositions more than words and pictures. What makes this one special is how every page turn takes you to a new visualization of something only the comics form can achieve -- more split screens and faster than the movies, more beautiful drawings in less space than any gallery exhibition, more time covered than any novel can manage no matter how small the words are printed -- and it still all makes such simple and glorious sense, is put into such seamless rhythm by the little numbered dates McGuire leaves in the panels’ top right corners and nothing more. Any single spread is a picture of something that cannot be done anywhere but here, something native to comics. See an arrow fly inch by inch, spread after spread, while the panels around it shuttle us across thousands of millennia using the same amount of space. See events separated by decades refer to each other as simultaneously as two people saying the same thing to one another at the same time -- five twentieth-century mothers dandle their newborn babies in the same room against five different wallpaper patterns, which we can see both the installation and the disposal of if we turn a few pages. See an old man cough himself to death in a comfortable suburban living room as the smoke of Ben Franklin’s house fire billows around him from less than a hundred yards and more than two hundred years away. Perhaps if we could simultaneously hear every different interpretation of the same symphony ever staged, the effect would be similar. But we have this book.

My favorite sequence -- it is subtle, so persuasive is the flow of the book, but there are orchestrated segments, like scene changes in a dance performance -- begins with a hilarious line straight out of a Michael DeForge-style absurdist laff comic. “My own father is becoming a terrorist!” fumes Ben Franklin’s son, hours before a carriage carries the old man and his grandson back home and into an explosive political argument, which tumbles into a montage of every insult ever hurled in McGuire’s house over the centuries, every glass or plate or mirror ever broken, every item lost, every intimation of approaching infirmity or insanity -- before humanity’s grip on the narrative breaks, like a singer’s voice failing him, and we are left with spread after single-image spread of the book’s landscape centuries human life ever touched it, beautiful forms and colors advancing and interlocking in the kind of harmony that, glimpsed in real life, leaves one struggling to doubt intelligent design. Slowly, the Lenni Lenape Indians appear on the scene, and a sexual encounter between a young brave and maiden is interrupted by a bird crashing through a window into the house built on the ground they paw hundreds of years after the fact.

By this time we’ve long since known that the house will give way to the elements within another century and change. The triumph of entropy is total, as anyone alive to the gorgeous visions of the natural world McGuire provides throughout Here can plainly see. But rather than painting humanity’s brief ballet before his viewpoint as something perverse and separate from nature, McGuire finds a beauty in us that is indistinguishable from the beauty in the rest of his book. In Here, we are a particularly fascinating species of flourishing fauna, a force as elemental in our time as the sun or the ocean. We’ve never seemed so small or so big, so important or so meaningless. Neither have comics. The pink lady remembers why she came in here again, and picks up a small hardcover book.