A number of the criticisms levied at Craig Thompson's highly ambitious new work, Habibi, have been aimed at political byproducts of the book rather than the story itself. The most prevalent brickbat has been that of Orientalism, the Western tendency to tell stories set in Asia or the Middle East and imbue them with a sense of mystery that is based on cliché and stereotype. Whether or not the charge of Orientalism is intended as a slight, there's no question that the artist is adopting (usually in a surface manner) tropes belonging to the Other in order to bring a sense of exoticism to the story. Other criticisms of the book include accusations that it contains racist and sexist imagery. These are all issues that deserve consideration and discussion, but to a large degree, they are also beside the point. The question I would ask is: Did Thompson succeed in what he set out to do? While Thompson created a great deal of interesting comics art and many memorable passages, the answer ultimately has to be "no."

A number of critics have commented on the book's overstuffed feel; it feels less like a single coherent work than a multi-volume series smashed into a single text. The jarring chapter breaks certainly don't help Thompson to achieve the sort of cohesion that Blankets (his previous work) has, for example. More to the point, it seems as though Thompson kept coming up with ideas and ways to expand on these ideas, and he chose to try to include everything. The story at its essence is about the odyssey undertaken by a young girl and a younger boy, both separately and together, in a fictional Middle Eastern kingdom called Wanatolia, in which they encounter not only ancient story tropes but also modern technology. The girl raises the boy as a sort of son/brother until they are separated for several years, and then reunited at a terrible cost. That cost threatens to separate them again permanently until both find a way to work through it, and they live happily ever after. Along the way, Thompson throws in references to The Arabian Nights, eunuch culture, the Koran, Islamic mysticism, calligraphy, the fine details of harems, plumbing, and a half dozen other subjects.

Thompson has discussed this kitchen sink approach, claiming to care more about story moments than a tidy plot. If the book digresses into discussing the history of alchemy for a dozen pages, so be it. To his credit, many of those sequences did wind up providing a certain richness of detail that strengthened the plot. The problem is that as a reader I could see this was all artifice, a way for the author to explore problems and ideas that interested him but didn't necessarily make for a compelling narrative. The reason that the book ultimately fails is that the characters simply aren't compelling enough as characters; instead, they are closer to story devices.

Thompson has discussed this kitchen sink approach, claiming to care more about story moments than a tidy plot. If the book digresses into discussing the history of alchemy for a dozen pages, so be it. To his credit, many of those sequences did wind up providing a certain richness of detail that strengthened the plot. The problem is that as a reader I could see this was all artifice, a way for the author to explore problems and ideas that interested him but didn't necessarily make for a compelling narrative. The reason that the book ultimately fails is that the characters simply aren't compelling enough as characters; instead, they are closer to story devices.

Habibi reminds me a little of Alan Moore & J.H. Williams's Promethea, another visually stunning comic that spends a lot of time mapping out the author's obsession with diagramming reality by way of an ancient, mystical system of understanding. The study of structure in that book also centers around how the mind, body, and spirit act together, with a particular focus on breath and sexuality. Promethea's ultimate problem as a coherent work is that it winds up resembling a lecture more than a story, with characters who are little more than mechanisms for delivering that lecture. In Habibi, the protagonists Dodola & Zam shift as devices from chapter to chapter, but they are ultimately simple vehicles of misery, objects for Thompson to manipulate in order to explicate the subjects he is interested in. The digressions in the story have nothing to do with the plot, but they ultimately have nothing to do with the characters qua characters either; instead, the focus is on whatever aspect of the culture Thompson created and wanted to expand upon in further detail.

That's the essential nature of Habibi's failure as a work: it's an exercise in world-building masked as a love story. Even the happy ending that Thompson contrives has more to do with a logical, almost apologist application of rules rather than an act of real will by its protagonists. A text-only chapter in which Zam contemplates suicide because he knows he will never be able to provide Dodola with children winds up being nothing more than a rational religious argument he holds with himself. Contrast this with Jaime Hernandez's recent "The Love Bunglers" story in Love & Rockets. This story also features two characters finally united after years apart, both by choice and by fate. The key difference is that as a reader I felt that these characters are active agents of their own fate, acting against their own best interests due to their own human foibles. They weren't simply being buffeted by forces beyond their control. Hernandez imbues these characters with a life that goes beyond plots and narratives, meandering from story to story in a manner that nonetheless accrues years of rich character detail.

Another key difference in approach is that Hernandez is able to depict emotion through gesture and dialogue, whereas Thompson leans more heavily on sentimental melodrama and cliché. Hayley Campbell compares Thompson to Will Eisner in this magazine's recent roundtable on Habibi, and I couldn't agree more: Thompson is a modern Eisner, for better and worse. Without Thompson's astonishing and virtuosic visual sense, Habibi wouldn't be worthy of any real discussion. His attention to detail is astonishing. His devotion to latching onto and exploiting metaphor to the nth degree is simultaneously inspiring and exhausting. Unfortunately, his reliance on stereotype and cliché undermines his work as much as it did Eisner's. Because for all of Eisner's structural brilliance and ambition, his characters talked liked over-the-top stage characters. Racial, sexual, and ethnic stereotypes abounded in his stories. In Habibi, the reader is presented with dark-skinned African characters who talk in quasi-American slang. The way Thompson depicts cross-dressing eunuchs shows a fairly startling lack of understanding of transgendered issues today, something that comes into play because of the modern tone of their dialogue. His idea of comic relief is a dwarf who farts when he's nervous. The average Arabic man is depicted as a rapacious, untrustworthy monster.

Another key difference in approach is that Hernandez is able to depict emotion through gesture and dialogue, whereas Thompson leans more heavily on sentimental melodrama and cliché. Hayley Campbell compares Thompson to Will Eisner in this magazine's recent roundtable on Habibi, and I couldn't agree more: Thompson is a modern Eisner, for better and worse. Without Thompson's astonishing and virtuosic visual sense, Habibi wouldn't be worthy of any real discussion. His attention to detail is astonishing. His devotion to latching onto and exploiting metaphor to the nth degree is simultaneously inspiring and exhausting. Unfortunately, his reliance on stereotype and cliché undermines his work as much as it did Eisner's. Because for all of Eisner's structural brilliance and ambition, his characters talked liked over-the-top stage characters. Racial, sexual, and ethnic stereotypes abounded in his stories. In Habibi, the reader is presented with dark-skinned African characters who talk in quasi-American slang. The way Thompson depicts cross-dressing eunuchs shows a fairly startling lack of understanding of transgendered issues today, something that comes into play because of the modern tone of their dialogue. His idea of comic relief is a dwarf who farts when he's nervous. The average Arabic man is depicted as a rapacious, untrustworthy monster.

To be clear, I don't think Thompson is racist or sexist. It's quite obvious that Habibi is not meant to reflect reality, but instead act as a modern fairy tale integrating aspects of ancient Western stereotypes of Arabic cultures, actual Islamic beliefs & practices, and the ways in which capitalism has led to the destruction of Third World countries. Indeed, in many respects Habibi goes out of its way to respect Islam, and I suspect that the fact that Thompson started this book shortly after 9/11 is no coincidence in that regard. Not so much because the book appears to be a comment on that event, as that it seems to stem from a desire to depict Islam in a manner that was different from the popular Western understanding of it. I don't think it's an accident that the book's heroes are actual believers, while the godless characters are the book's villains. (As an aside, this is an interesting counterpoint to Blankets, wherein most of the religious characters are depicted as monstrous, ignorant, or both.) Thompson himself even provides a degree of metatextual self-critique when Dodola chides others for enjoying one of her stories that is sexist and misogynistic. That doesn't stop Thompson from appropriating such images for himself, nor does it make such images less troublesome, but he is at least aware that he's treading on sensitive ground.

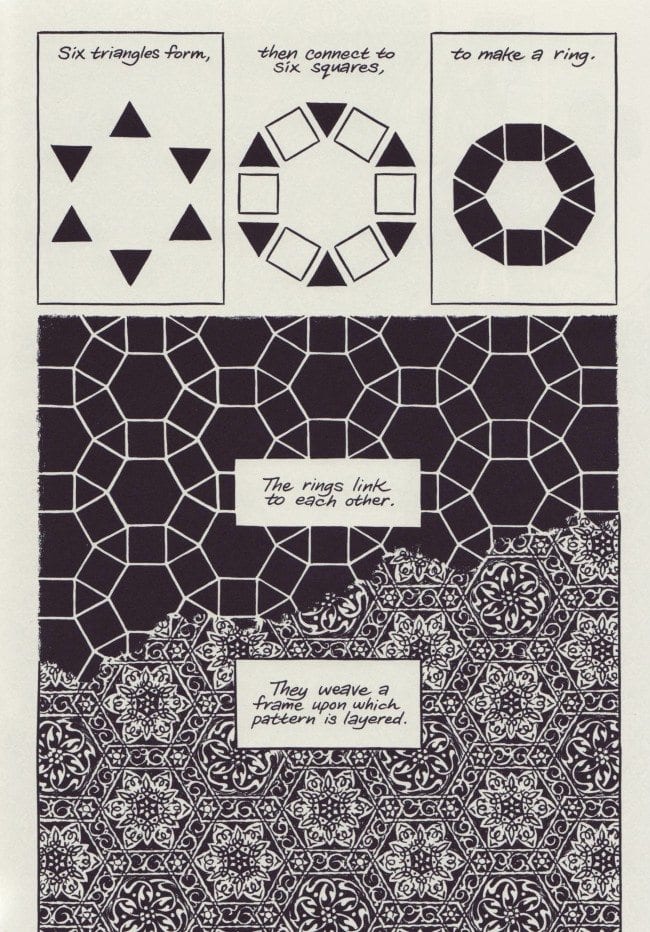

Thompson has a tendency to depict his heroes as impossibly noble and self-sacrificing and his villains as moustache-twirling caricatures. This is unfortunate, given the startling and clever virtuosity on display in terms of his art. The way he composes pages to incorporate the sort of decorative patterns found in the Middle East is amazingly beautiful, and further reinforced by how Thompson breaks down and analyzes why those patterns are important. The key visual idea of the book is that word and image in Arabic calligraphy are united in a way they aren't in English. Thompson has always seemed to have an aversion for negative space in his work, but that quasi-graphomania is put to good use here in the way each page is designed. His heavy brush gives each of the book's pages a powerful denseness, a weight that compels the reader to dwell on its images. There are times I wish he trusted his ability to evoke a world through images alone even more, because his narrative sometimes steps on his art in awkward ways--especially via the frequently hokey and overwrought dialogue. The brilliantly realized metaphor of language as water, symbols flowing like liquid to create and destroy, is undercut by the narrative's frequent hammering of this point home for the reader, as if it wasn't already clear.

That's the story of reading Habibi for me: for every remarkable thing Thompson does in creating this massive tome, he makes an egregious misstep. But I'm not sure a heavier editorial hand would ultimately have made much of a difference, because Zam and Dodola would still be the same characters: two people buffeted by fate holding on to each other simply because they were there for each other all along. Their relationship lacks complexity or nuance; more than anything, it feels like a fairy tale artifice rather than something with emotional authenticity. This has been my major critique of Thompson throughout his career: the only emotional relationship that ever rang true in one of his books was that between the Craig character and his brother Phil in Blankets. Even the romance depicted in that book feels contrived, a matter more of imagination than reality. The way he depicts sex and sexuality in that book—and certainly in Habibi—rings false; I cringed at the the line in which Dodola says that for a woman, the inspiration for sex is the narrative. It's yet another case of Thompson relying on stereotype instead of trying to get at the root of being human and being in love.

There were times I thought that Thompson deliberately stacked the miserablist deck so as to overcome the contrivance of the central relationship. So many ridiculously bad things happen to these innocent, noble characters that one can't help wanting them to be be happy. After rapes (lots and lots of rapes), beatings, drownings, disease, disfigurement, the murder of Dodola's baby, public humiliation, ecological disaster, and capitalist hegemony, it's a relief to see them finally paddle up the river, away from Wanatolia, with their newfound daughter completing them as a family. It's a relief, but it also feels entirely contrived. Thompson doesn't do much to connect the reader to the characters other than torture them for 600+ pages, alleviated by occasional oases of idyllic living, followed by more torture and misfortune, until it all suddenly stops. Thompson is a huge talent, but at this point I wish that he'd do something on a far smaller scale, perhaps something directly autobiographical but modern. I'd like to think that he's capable of nuance and able to depict quotidian events in a meaningful way, but for now we just have the ambitious but ultimately bombastic works he's produced to date.

There were times I thought that Thompson deliberately stacked the miserablist deck so as to overcome the contrivance of the central relationship. So many ridiculously bad things happen to these innocent, noble characters that one can't help wanting them to be be happy. After rapes (lots and lots of rapes), beatings, drownings, disease, disfigurement, the murder of Dodola's baby, public humiliation, ecological disaster, and capitalist hegemony, it's a relief to see them finally paddle up the river, away from Wanatolia, with their newfound daughter completing them as a family. It's a relief, but it also feels entirely contrived. Thompson doesn't do much to connect the reader to the characters other than torture them for 600+ pages, alleviated by occasional oases of idyllic living, followed by more torture and misfortune, until it all suddenly stops. Thompson is a huge talent, but at this point I wish that he'd do something on a far smaller scale, perhaps something directly autobiographical but modern. I'd like to think that he's capable of nuance and able to depict quotidian events in a meaningful way, but for now we just have the ambitious but ultimately bombastic works he's produced to date.