Let me tell you a little something about a guy named Joe. Born the youngest of six in the tenacious steel town of Hamilton Ontario (aka “The Hammer”), he was raised on a rural Christmas tree farm and at the age of 17 started working the night shift in a box factory to support his wife and young daughter.

No, these are not lyrics from an obscure Merle Haggard song, but rather evidence of Joe Ollmann’s blue-collar bonafides. It’s a pedigree that the cartoonist has worn on his ink-stained sleeve since he began his professional career in 1988 with the self-published Dirty Nails Comics (the title of which your Honor, I submit as Exhibit A).

In the 33 years since, Ollmann’s working-class origins have served as his creative gravity, grounding his best work in a palpable reality. Whether it’s the beautiful-sad short stories in his Doug Wright Award-winning This Will All End in Tears in 2006, the blundering semi-autobiographical protagonist in his first graphic novel Mid-Life in 2011, or his 2017 biography of the notoriously self-destructive wild man William Seabrook, Joe can’t shake his affinity for the messy struggles of real people.

Take Caleb Wyatt, the protagonist of Ollmann’s latest graphic novel Fictional Father, an entitled middle-aged struggling artist and recovering addict who when we meet him is living off the not-so-goodwill of his ludicrously wealthy father, a successful cartoonist who he—of course—loathes. And he’s also neglecting his relationships with his long-suffering mother and his patient, doting husband. On paper Cal is kind of a shitty human. And yet, there wasn’t one panel in the book’s 212 pages that I wasn’t rooting for the son of a bitch.

This gets to the heart of Ollmann’s storytelling powers: his ability to conjure the ragged humanity in each his characters regardless of their tax bracket or socio-economic status.

It’s there foremost in his writing, which avoids hot takes and quick judgements and refuses to let any of his characters (or readers for that matter) get off easy. But it’s also present in his art, which boasts a scruffy, craggy line that leaves no forehead unwrinkled, no skin unblotched, seemingly declaring to the world “Life isn’t tidy, so why should my art be?”

This one-two punch combines once again to great effect in Fictional Father, his new book with Drawn and Quarterly (and his first in full color) which explores a fractured and fractious relationship between Jimmi Wyatt, a world-famous newspaper strip cartoonist, and his aforementioned only child Cal, who despite being in his 40s is still trying to find his footing in the pop-culture shadow of his dad’s making.

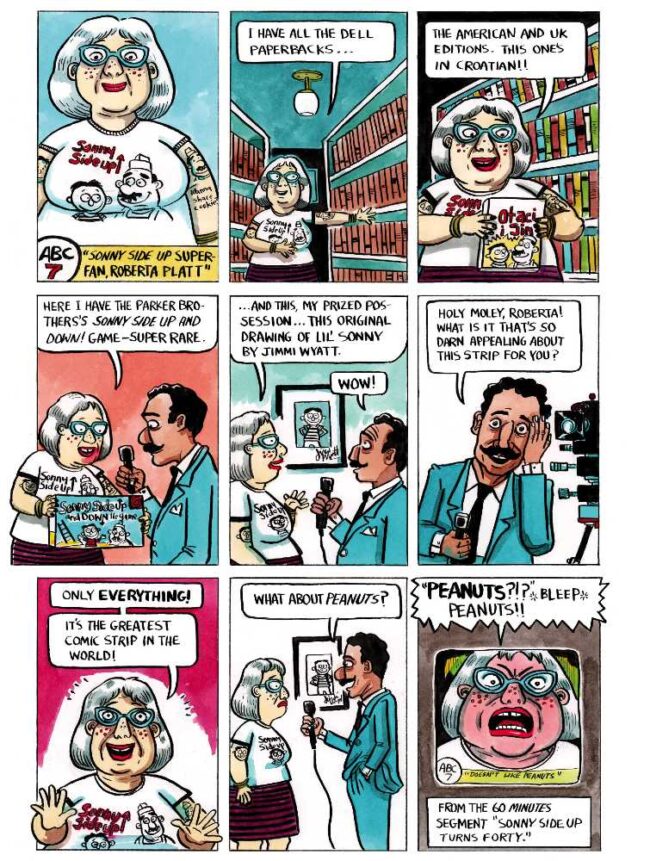

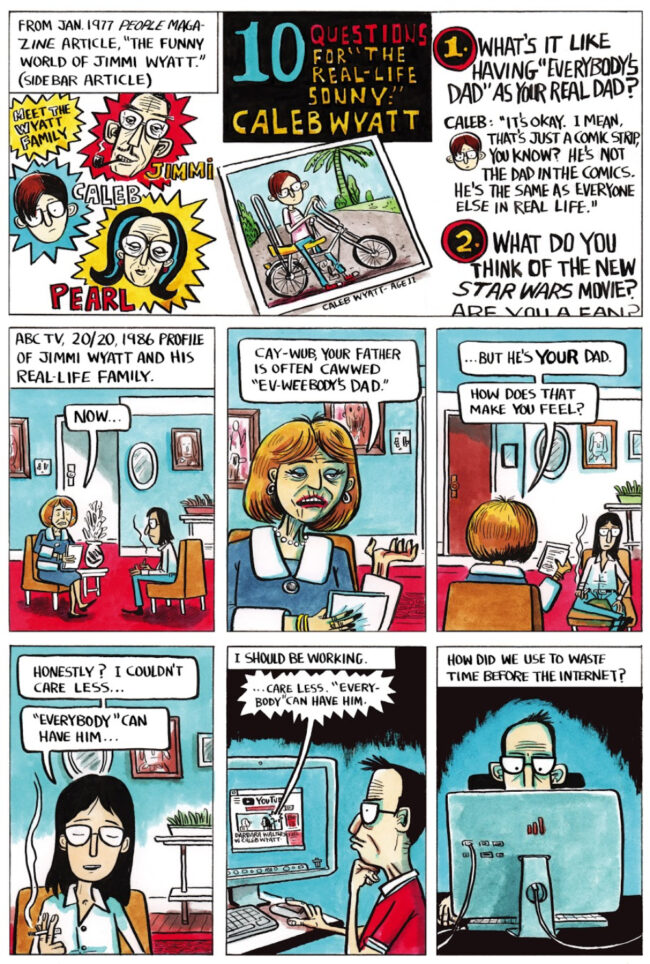

Jimmi is the ascot-clad creator of Sonny Side Up, a comic strip about a single dad named Poppy who struggles to balance the daily responsibilities of running a diner with the obligations that come with raising a child. Sonny is so cloying that it makes Dennis the Menace seem like Jimmy Corrigan, so of course it’s a massive hit that has made Jimmi very rich and very famous (Tony Bennett is a golf partner; Barack Obama is an admirer).

But where Jimmi’s readers see the widespread popularity of his strip as a hard-working success story, his wife, Pearl, and son experience a different truth. To them Jimmi is an utter fraud: an unfaithful and indifferent husband, a harsh and neglectful father, and a cruel taskmaster to his cadre of loyal employees. (And yes, Ollmann wants you to know that he is aware of the parallels to real-world cartoonists like Hank Ketcham.)

While Pearl has come to bitterly accept her husband’s transgressions as part-and-parcel of the fame and fortune, Cal remains haunted by, and to some degree defined by, them. As a young man he expresses this by taunting his father in TV interviews and by publishing an art-school comic, Sunny Side Downerz, that takes underground aim at his hypocrisy.

Now, with his youthful rebelliousness behind him, the adult Cal divides his time between maintaining his sobriety, working on paintings for a solo exhibit, and obsessively Googling (and buying) Sonny Side Up ephemera. His struggle to forge his own identity is pitiful, but a natural consequence of poor parenting. Unfortunately, his innate selfishness and lack of any adult purpose is eroding his relationships with those closest to him: his marriage to James is unraveling before his eyes and he’s blind to the suffering of his mother, who is as much of a victim of Jimmi as he is.

All of which poses the age-old question: Are we destined to turn into our parents? The tragic thing is that Cal is aware of what he has become; early on in his story he wonders “Do we always become the thing we hate most, or do we pre-emptively hate that trait because we sense it in ourselves?”

This is the central theme of Ollmann’s book and one our hero must wrestle with until the ultimately life-affirming final pages. Before he arrives at his destination though Cal must run a gauntlet of indignities, humiliations, heartbreaks, and poor decisions (many of his own making), but thanks to Ollmann’s confident, assured storytelling it’s a journey well-worth taking.

While en route, keen-eyed readers will revel in the author’s unabashed love for comics, which manifests in a series of industry gossip, cartoonist cameos (it’s Albino Seth!), and hopelessly nerdy in-jokes that I am equal parts proud and embarrassed to cop to enjoying (shout out to all the Floyd Farland super-fans!).

A final note should be made about Ollmann’s shift to full color following more than three decades of toiling in the black-and-white salt mines (recent flirtations with duotones notwithstanding). I’ll admit to having reservations about the colorization of Ollmann’s signature style, which seems to have served him so well over the years. These reservations were reinforced when I learned that he was secretly color-blind. I mean what’s next: a signature fragrance from a supermodel with no sense of smell?

According to Ollmann, he always envisioned the book in color and used transparent primary-colored inks and a color wheel to help him achieve his vision. The results are revelatory and refreshing, with Ollmann bringing new texture to his art and new life to his world-worn characters. After all, nothing is ever black-and-white in Ollmann’s stories anyway, right?