The first thing one notices about Nina Bunjevac's work is its density. Her cross-hatching and stippling pounds the reader, letting them know that these images are not going to let them go easily. Her skill as a draftsman is astounding, especially given the labor-intensive methods she chooses to employ. In her first book, Heartless, Bunjevac combined a heavy use of blacks with a cartoony line that was both whimsical and sinister. Her character design was cute, but her characters lived in a grim and unforgiving world. I noted in a review that her comics were a combination of Drew Friedman's early pointillism, Kim Deitch's oddly cartoony characters, and Phoebe Gloeckner's hyperrealism. Her new book, Fatherland, is an expansion on one of the stories from Heartless titled "August, 1977", about the accidental death of her father, who happened to be a Serbian royalist terrorist, and a letter her mother wrote her after she took two of their children with her when she left.

In many respects, this book seems to have been an exercise in problem-solving. What would be the best way to go about explaining the events that led up to his death, especially since that explanation would involve going back a couple of generations as well as the contentious history of Balkan politics? One could go from the general to the specific, ending the book with his death. The problem with that approach is that it would turn too much of the book into a history lesson, with little human grounding. Ignoring the history and context of the event would be too confusing. Bunjevac struck a different path that used scenes from the present day (a la Maus) to create enough context for the reader so that the impact of his death would have the desired impact. The second part of the book provides history and detail, and then Bunjevac cleverly revisits the events she described in the first part of the book at the very end, this time from a different perspective.

The book opens with Bunjevac talking to her mother Sally in the present day, showing her an internet image of the house they used to live in in Canada. The way Bunjevac frames this scene is interesting, as her dense, hyper-real style gives her figures not so much a sense of naturalism as an almost grotesque, heightened sense of each character's emotional state. The effect is not one of comforting, everyday images, but one of horror. Unlike simpler, more iconic images that one can project a greater "firmness" onto to fit one's specifications, there's a "hard" quality that every drawing in this book possesses that forces the reader to meet them on Bunjevac's terms or not at all. Thomas Ott does the same sort of thing in his comics to depict a more traditional kind of horror.

The next part of the book goes back to that house in 1977, when Bunjevac was a toddler. Her mother tucks the children in, taking the extra step of blocking all the windows with furniture for fear of having a bomb thrown through one of them. There's a chilling page where Sally has already laid out a plan to leave, knowing that her husband is probably responsible for a recent bombing. There's a subtext of negotiation as she calmly suggests taking the kids to see her parents in Yugoslavia, and her husband, with his face clouded in shadow, agrees to her request—with the caveat that his son would stay with him. Deadpan to the last, she leaves with the girls, knowing that she would not be coming back, and this makes the otherwise calm and normal-seeming goodbye that much more tense.

"Tense" is a good word to describe much of the rest of the book. Sally moves in with her parents. Her mother welcomes them with open arms, but she is so politically diametrically opposed to her son-in-law that she refuses to allow discussion of him in the house and tells her grandchildren that he is a cold-blooded killer. There's a masterful scene where Bunjevac's sister is celebrating her birthday while Sally and her mother are screaming at each other, and the kids are trying to be as quiet as possible. Here, the "hard" quality of Bunjevac's style is at its best, as the reader is forced to live in the tension of that moment.

Bunjevac then introduces Balkan dream interpretation imagery, where dreaming of birds means you're about to receive important news and dreaming of meat is a sign of death. Her grandmother has dreams like this two days before Bunjevac's father was killed, an event that is received with such a level of resignation—including from the children themselves—that no other emotions could be registered on the page. The only reaction from her grandmother is to tell them not to go back to Canada or they will be killed.

The second section of the book is Bunjevac's quest for understanding and greater knowledge of the circumstances surrounding her father's death. There's a moment of clarity at the end of the first section where Sally says that her husband was emotionally abusive and ranted constantly about politics, but also points out that her mother was also emotionally abusive and similarly would not stop talking about her own war stories. It is an atmosphere where no one is allowed to express their feelings. Sally tries getting her son Peter back, but he refuses to go to Communist Yugoslavia, which was no doubt due to the influence of relatives. Bunjevac's account of her mother's visit ends with her mother insisting that Nina lock the door behind her, and coming back to make sure she did it; some habits die hard.

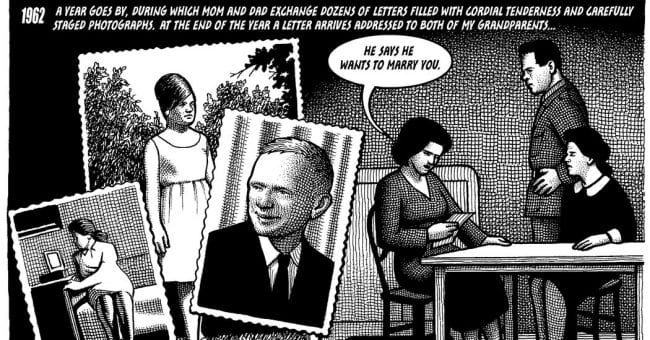

Bunjevac then delves into his family's history, which was one of heartache and struggle. This dovetails into the history of ethnic struggle in the Balkans, including the battle between the Chetniks (those loyal to the crown) and the Partisans (the communist resistance led by Joseph Tito). Young Peter Bunjevac's parents died when he was young after the war (his father at the front), but his reaction to this seems to have been psychopathic in nature, as he started killing neighborhood cats. Only his aunt believed in him as he grew up in military school. There, he saw communists taking over property and killing people at the slightest provocation, things that even Bunjevac's grandmother refused to justify. Peter started engaging in resistance behavior and was sent to prison before his aunt pulled some strings to get him sent to Canada. Incredibly, he met his wife via her mother when they became pen pals. Without meeting her face-to-face, they fell in love by the mail and she came to Canada to be with him.

It wasn't long before Peter got deeply involved with terrorist activities, with some friends of his glibly threatening Bunjevac's mother, who was not having it. Sally tried to hold out hope that he would change, that things would get better somehow, that he wasn't really putting his family in danger, but she eventually knew that her mother was right and that an "exit strategy" was needed. Peter was in a position where if he quit his group he would be killed, and returning to Yugoslavia meant prison. He wrote Sally, "I am too deep in shit and cannot get out of it." This time around, Bunjevac directs the focus on him in his last days, first when he unsuccessfully tried to kill himself and later when he accidentally (?) blew himself up with a couple of other terrorists. The last pages of the book, after her aunt Mara first hears the news, are a total departure. Using nothing but silhouettes and negative space, she depicts Mara falling into a hole, until she is reunited with her beloved nephew Peter again.

Bunjevac shows a remarkable degree of empathy for all involved. She acknowledges her father's miserable life and his aunt's position as the only person who believed in him. She acknowledges her mother's bravery and the burden she faced. She acknowledges her grandmother's hardness in the face of everything she faced in her life, but also her undying support for her daughter. Curiously, the one person we don't hear much about in the book with regard to her feelings is Bunjevac herself. She was too young to understand what was going on when her father died, too young to understand the politics, and she grew up in Yugoslavia at a time when it started to become more culturally open. The emotions that Bunjevac felt are all in subtext, as a product of the extensive research that she did. The empathy she felt for all added up to a hard-won forgiveness for all involved, especially her father. Bunjevac has little interest in arguing politics in the book, considering that the products of both sides seemed to be the same kind of murder and greed. Rather she is arguing against polemics in general, especially where they cross the line into dehumanizing behavior. It seems clear that Bunjevac's need to tell this story allowed her a sense of closure on the entire experience. This is a story that makes you pay attention to every awful detail, that doesn't let you forget which horrible things contributed to what terrible consequences. There is no winner to be found, only survival and the bonds of family.