Cathy Malkasian began her career in animation in the early 1990s. If you have kids, or like TV animation, you’ve probably seen some of her episodes of Curious George and The Wild Thornberrys. She turned her creative attention to graphic novels in the mid-2000s. Her first book, Percy Gloom (2007), earned her an Eisner Award nomination and its Most Promising Newcomer Award.

Eartha is Malkasian’s fourth graphic novel. It, too, has been nominated for an Eisner Award, and garnered critical acclaim. On the surface, it looks like a Tolkienesque fantasy, with all the tropes that genre suggests. It is such a fantasy, but it uses its potentially groan-inducing trappings to tell a layered, metaphorical story that seems just right for the America of today.

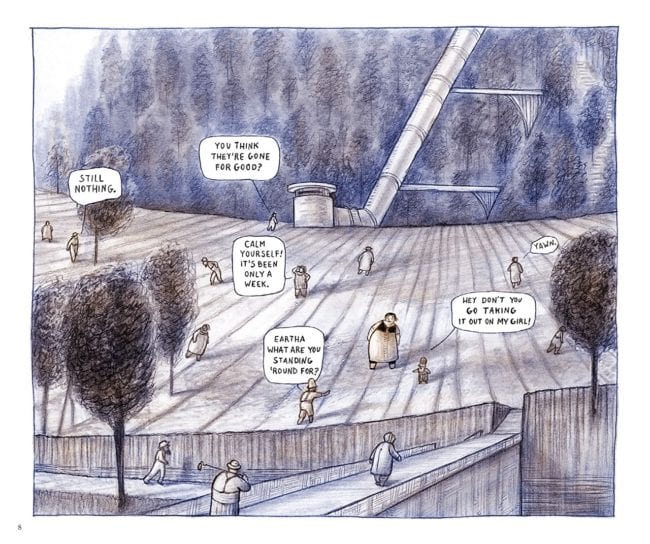

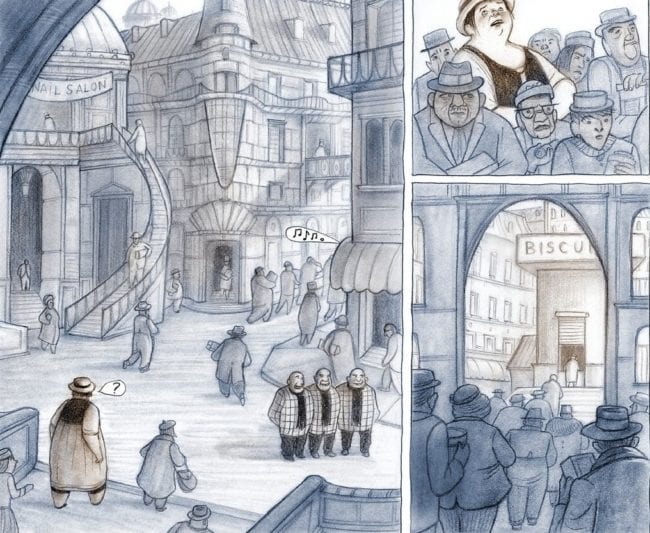

The world of Eartha is reminiscent of Percy Gloom, with its winding cobblestone streets, byzantine alleyways, and rich foliage. The books share a vision of blundering, over-complex, and comical bureaucracy. The reader is aware that they’re in a thought-out, obsessed-over world—one that suggests other artists, from Fred Opper to Maurice Sendak, but doesn’t seem derivative of those works.

Malkasian’s subdued color palettes, careful graphite renderings and versatility of unusual body language and facial expressions are impressive throughout Eartha, which takes its time to set up its story and introduce its characters.

The book’s two major themes—the split between rural and urban living and the insistent presence of social media—keep Eartha from being another Joseph Campbell-cliché Hero(ine)’s Quest for Something, as this type of fantasy story too often succumbs. A gentle, sometimes dark humor further leavens the message. Its metaphors aren’t delivered with a solemn face; nor is a moral preached. Right and wrong in Eartha are matter-of-fact; sometimes the latter is underlined more than necessary, but the artist’s delight in the human comedy wins out.

Eartha begins in the rural Echo Fjord, a humble agrarian utopia whose residents till the fields and, in better times, harvest the dreams of the far-off City across the Sea. Eartha, described in the book as “big as a boulder and softer than the moss that grew on it,” towers over the other Fjorders and is friend to all.

The dreams manifest themselves as glowing lights in the ground which sprout to reveal the dreamer’s self-image, as they enact their subconscious drama out in the wild. These internal dramas and comedies reveal potentially embarrassing and shaming things about their dreamers. For generations, the Fjord people have welcomed these emissions and watched their brief psychodramas before they fizzle away.

The dreams give the Fjord people a sense of the larger world. Their sudden abatement sends the community into a funk. Eartha witnesses a monumental dream of a city child’s in which the moon falls from the sky and seems to land in the fields of the Fjord.

This dream causes her to be sent to The City, under laughably false pretenses she is too naïve to detect, by Old Lloyd, the irascible archivist of the city-generated dreams. He has a bigger reason for dispatching Eartha to The City—he wants to find out why the dreams, which were once innumerable, have dwindled down to a drizzle.

I know… it sounds hokey. As a dedicated non-fan of the fantasy genre, I was a tough sell for this book. Malkasian’s stories have clichés as their foundations. How she wriggles through them and twists them around (and inside-out) is what makes Eartha compelling.

Eartha was created just before a certain unrestrained egomaniac gained control of the White House. Malkasian must have sensed something in the air. Her charismatic, volatile City leader, Primus, shares some off-putting and abrasive behaviors with You-Know-Who, but is not a caricature or satire of You-Know-Who. He embodies the pettiness and self-importance of the unchecked male ego—strutting and preening, absurd in a tiara and checkered sports jacket, seemingly sure of himself as he struggles with his confused libido and sublimates it through acts of greed and violence.

Primus has hooked the City’s residents on buttery pieces of shortbread stamped with random ennui-causing phrases (FAT JACKASS OOZES CALAMITY, reads one biscuit). These fattening crumbles of blank verse have the urban dwellers in hysteria. Due to this citywide focus on the cookies and their depressing messages—to which the residents are addicted—their dreams have almost ceased to be. A metaphor for Facebook, perhaps, or for the compulsive way we ingest social media, which confronts us daily with the ugliness of the world, alongside adorable cat videos and the occasional grain of good news.

Malkasian’s love of eccentricity steers this story. Despite the narrative clichés—country vs. city, fish out of water, the evil empire that must be toppled—Eartha surprises the reader with its loving deviations from the genre ticker-tape. Malkasian enjoys building scenes around cranky, self-absorbed characters. Virtuous or villainous, Eartha’s cast relishes their opportunities to vent their spleens, ramble about the events of the past or pass time with chit-chat. The rantings of Old Lloyd, the archivist, are delightful. Malkasian has a fine ear for dialogue; her characters rarely utter the mundane.

Eartha’s graphics support its narrative with grace. Malkasian’s style evokes children’s books and (no surprise) animation. Her skill with the human figure—which she deftly caricatures and endows with fleshy presence—is a delight to encounter. She distorts these figures in a manner that recalls early 20th century American newspaper cartooning, although animation’s squash and stretch principles are a more likely source. Her modeled monochrome figures, often up-lit for a theatrical gaslit effect, are commanding and convincing. Much of the book’s success is via its solid, expressive artwork and its control of color and its absence.

Much of Eartha resembles a tinted silent film, with rich sepias and hints of slate blue and subdued green. Restrained pastel blue and violet enters the story as needed, to highlight changes of venue and mood. So thorough is this palette that the absence of traditional bright colors isn’t noticed—or needed.

The elision of strong color is broken by three full-page section headers that show Malkasian’s skill with vivid pastels. They’re startling interludes amidst the earth-tones that dominate the book. It’s impressive to see how much the artist can achieve without a broad palette of colors.

Eartha is the rare fantasy story that can be read without the sense that you’re about to be taxed by endless clichés. Like the animated features of Hayao Miyazaki, it offers elements of escapism without the escape. It offers a timely reminder for us not to get side-tracked by the hysteria around us, or to pretend that we can wish away offensive behavior and aggressive personalities. At its best, Malkasian’s Eartha collides genre tropes and painful truths in a charming, thoughtful and sometimes edgy entertainment.