In Drawing Power, edited by Diane Noomin and dedicated to feminist icon Anita Hill, over 60 women cartoonists of diverse ages, races, backgrounds and circumstances from all over the globe share their stories of surviving sexual violence, harassment and intimidation. They recount their experiences with fury, horror, sadness, weariness, defiance, bruised resilience, and yes, even humor.

Comics are a uniquely visceral method means of administering truth, and this big, wide-ranging collection delivers it in spades. Painful subject matter aside, this is a strong, varied anthology, smartly curated, and boasting a truly impressive talent roster, including personal-favorite creators along with many talents new to me.

The stories reflect a wide range of experiences and varieties of abuse, from flat-out sexual assaults to insidious harassment in the workplace to objectification in general. Some cartoonists, like Lee Marrs with “Got Over It” and Mary Fleener with “Consensual Rape,” excavate and examine single events from long-ago. Marrs describes fending off a would-be rapist in the courtyard of her apartment building, then suffering the lingering after-effects, with new-found fear altering her behavior (“I never went into the courtyard again.”). Meanwhile Fleener, who had never told anyone, including her husband, about being drugged and raped by a friend-with-benefits back in the 70’s, is spurred by the burgeoning #MeToo movement in 2017, to “spill her guts” about the experience. “I wept openly,” she says. “I was finally, officially pissed off.”

Other cartoonists recall multiple incidents, exposing the sexism, misogyny (and its equally evil twin, homophobia) firmly imbedded in the culture. At the outset of “Noncompliant” Jennifer Camper tells us “I’ve worked very hard not to be a victim. But even strong people have times when they are vulnerable.” She proceeds to draw several unhappy memories, some of which include being physically attacked. In “…Let Me Count the Ways,” Katie Fricas focuses on micro- (as well as macro-) aggressions, that include receiving rude, unasked-for “beauty tips” and enduring inappropriate invasions of space. Carol Lay’s two-page “A Sampler of Misdeeds” describes, in a comparatively light-hearted manner, several incidents, including both male and female coworkers making inappropriate remarks to her, before delivering her brutally blunt final panel: “Then there was the time I drank too much at a party and a young man led me into a bedroom and raped me.”

Siobhán Gallagher’s “Hanging with the Guys” is another comic with a sucker-punch of an ending, in which Gallagher, surrounded by a group of male friends, gets a rude reminder about her status as “weaker sex”.

Some creators relate being courted in disturbing fashion by unwanted suitors. In “I Don’t Even Like Sunflowers” Scotland-based cartoonist Maria Stoian has a neighbor who simply can’t take the hint, and in fact accuses Stoian of “being cruel” when she politely but with finality tries to make her disinterest in his affections clear (and no, he still doesn’t quite give up after that). Meg O’Shea in “Asian Girls” describes having a party conversation with a stranger in which he tells her “I’ve got a bit of an Asian fetish.” Even worse, during their conversation, O’Shea tells us, “It kept coming up,” until the guy finally grabs at her. “What does it mean to desire a person because of their race?” O’Shea asks rhetorically. “And what informs those conclusions?”

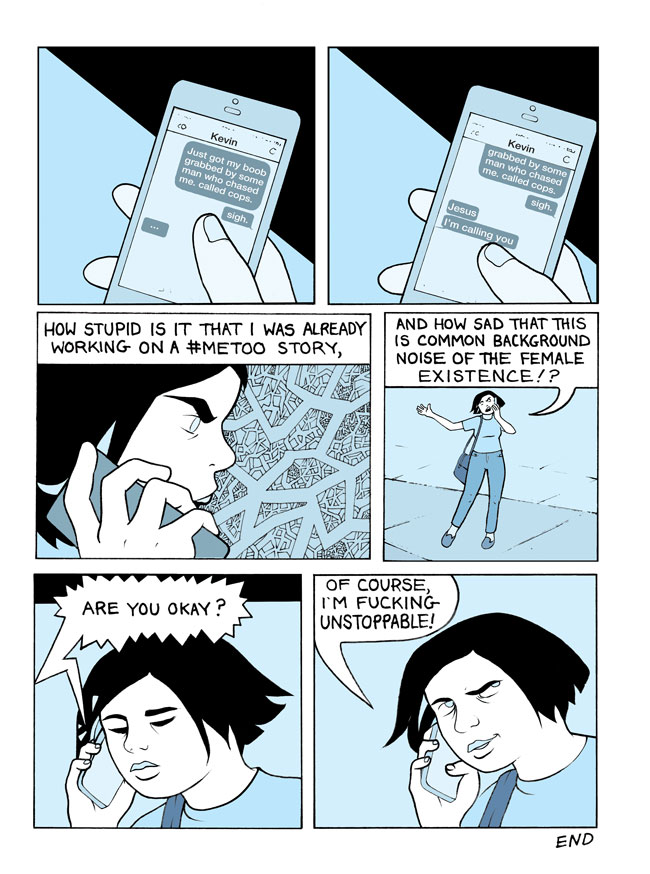

Several other creators recount harrowing experiences at parties or in bars, where they ran afoul of predators looking for the vulnerable and/or inebriated. My favorite of these works are “Bailanta” by the talented Ecuadoran-Columbian artist Powerpaola, and “Alibi” by Bridget Mayne, whose grotesque style captures her victimizers perfectly. In a similar vein, Miss Lasko-Gross describes being shamelessly groped in broad daylight on a city street in “Ever-Present.” We totally cheer her on as she proceeds to make a huge fuss, screaming after her fleeing abuser (“You are a piece of GARBAGE!”), calling the cops, and just refusing to take any shit. Righteous rage is a powerful thing.

In contrast, the trauma that often results in staying silent about abuse is vividly captured in Ebony Flowers’ story “Mr. Stevenson.” In it, Flowers fights off a coworker’s startling advances after hours at the school in which she works. She seeks refuge with an unwitting female coworker in another part of the building. Flowers is unable to tell her what has happened, and as the terror of the incident sinks in, her silence grows and grows. Flowers effectively translates the sense of disbelieving shock, isolation and helplessness. In an alternate situation, Soumya Dhulekar’s “Last Night was So Funny” depicts her describing a drunken night out with a friend in which the pair end up fending off an attack by a couple of guys who won’t take ‘No’ for an answer. As the title suggests, she recounts the episode to her friends as an incident to laugh off. The friends’ disturbed, concerned expressions at the end match the reader’s realization that Dhulekar is minimizing her assault, unable to admit its ugliness. It’s a powerful comment on the ways in which we seek to protect the Self.

As expected, there are tales of familial abuse. Carta Monir’s “Ready to Pop,” one of the most intense stories in the book, describes the awful, humiliating abuse Monir suffered as a pubescent at the hands of her father. “I almost threw up drawing this comic,” she concludes. In Kaylee Rowena’s “Photographs of Wild Beasts,” Rowena reveals with power and sorrow the fallout from growing up in an abusive household. Though she has long since cut ties with her father, she still lives with fear: “No one tells you how hard it is to escape and feel like you’ll always be running.”

Presenting family dynamics in a more positive light, there’s Tyler Cohen’s “She Bites Back.” In it, as Cohen goes to pick up her twelve-year-old daughter, Nene, from school, she ruminates about grim rape statistics (“One out of six women. One out of 33 men. 64% of trans people. 90% of victims are women”). When she learns Nene got into a scuffle with another student and bit him, she finds out that Nene did so to defend herself against being bullied. It is clear that Cohen takes comfort in knowing her daughter has already developed a strong instinct to fight back, and encourages this.

Among the comics about workplace sexual harassment, there’s MariNaomi’s “My Ally,” in which she has to deal with her one office friend–‑her general supervisor–‑being “a little too overly familiar” in a job she sorely needs. She effectively puts across her simultaneous feelings of helplessness (“terrified of the consequences, I endured his occasional inappropriate behavior and kept my mouth shut”) and shame (“Why aren’t I doing anything?”). In “Sausage Fest” Australian cartoonist Sarah Firth describes her ghastly experience of working in the Technical Services Department of a medical research institute. There she endures a steady stream of blatant harassments from male coworkers. Firth’s bright cartoony drawings make it all go down a little easier, but it’s still one of the more infuriating comics in the book.

The double-meaning of the book’s title echoes throughout. Some contributors comment directly on their work, literally describing their “Drawing Power.” Veteran Roberta Gregory offers up “Adult Comics,” a mini-history of her career. Along with some happy memories, she includes a generous sampling of the sexist treatment she’s received from male critics and readers. At the conclusion of “On the Road,” Israeli cartoonist Hila Noam depicts herself at her drawing table, creating her story for this collection and acknowledging the therapeutic aspects of doing so.

Some artists describe vividly the psychological impact of being objectified and of creating barriers of self-protection between themselves and the male gaze. In Liz Mayorga’s “Sleeping Fury” she tells how she tried to create an armor of heavy clothing (hoodies, military boots) to protect herself and others “from my hideousness.” But she learns later, with outrage, how “that armor was easily removed” by predatory men. In “A Lifetime” Barcelonan artist Lubabalo describes various incidents of strangers and acquaintances groping her, starting at age 10, and how often that affected the way she dressed and carried herself, avoiding wearing cute outfits that seem to bring her unwanted attention. “I can’t put an end to the abuses,” she concludes. “What I can do is tell what I’ve learned, what I do know.”

Those words beautifully capture Drawing Power’s impetus. Admittedly, there are those who may find this collection depressing rather than empowering, triggering as well as cathartic. Many of the creators write about intense feelings of powerlessness they experienced, and in doing so reclaim some of that power.

At the close of her piece about being raped as a teen, “Let’s Not Get It On,” Nina Laden declares, “I own this story. It’s mine. I survived it.” Emil Ferris adds to that statement a spiritual message in the book’s eloquent, open-hearted final story, “How Cartoons Became My Friends…Again.” Summing up her long journey from profoundly blocked artist to successful cartoonist, she writes, “I believe that we (you and me) are eternal creatures and as such we are more vast than anything we have experienced or will ever experience.” Drawing Power describes a lot of ugliness, but to great purpose. That is powerful indeed.