Dragon’s Breath, the latest release from MariNaomi, brings together numerous pieces of comics autobiography, most of which first appeared online at The Rumpus. Dragon’s Breath doesn’t follow a rigid timeline, but the collection does begin with a handful of entries about MariNaomi’s younger years, presenting moments from her adulthood later on. Through this sequencing, MariNaomi’s comics form a clearer arc than they did online, though they’re perhaps best enjoyed in single installments—the real appeal here is simply the number of good comics in one volume.

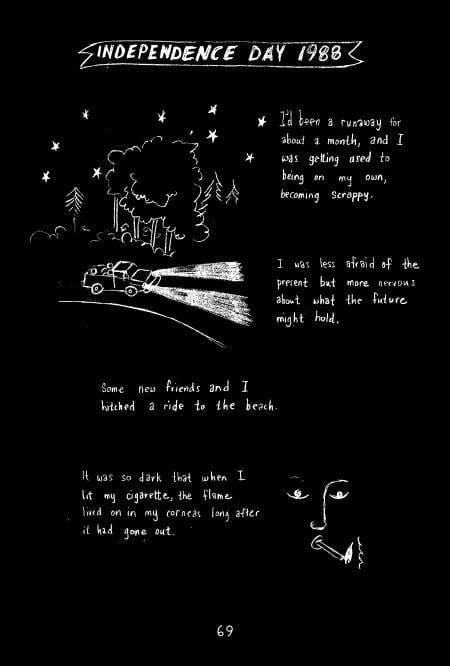

As a memoirist, MariNaomi has wit, focus, and a sense of when to stop telling a story. The comics in Dragon’s Breath are both compact and emotionally resonant. “Independence Day 1988”, for instance, depicts a moment from MariNaomi’s time as a teen runaway: the discovery of phosphorescent sand during a nighttime visit to the beach. The beach trip is a diversion from her runaway self’s recent worries—and possibly something transcendent. The three scratchboard pages of “Independence Day” tease the meaning of the moment, including enough details to charge the imaginations of readers and no more.

The brevity of MariNaomi’s storytelling has its hazards. “Have a Nice Day”, in which she vacillates about giving to a homeless person and then regrets her indecision, captures the events well enough but offers few insights beyond the sentiment that homelessness is an isolating condition. Even so, other comics share a specificity that gives their pages a concentrated power. “Coalinga”, a piece about the passing of a lonely neighbor, elevates what could be a comics retread of “Eleanor Rigby” through observations about sense memory and the chains of association that a mind forms. (Ray Bradbury once wrote, “If your boy is a poet, horse manure can only mean flowers to him.” The MariNaomi of “Coalinga” finds poignancy in the smell of cow droppings.)

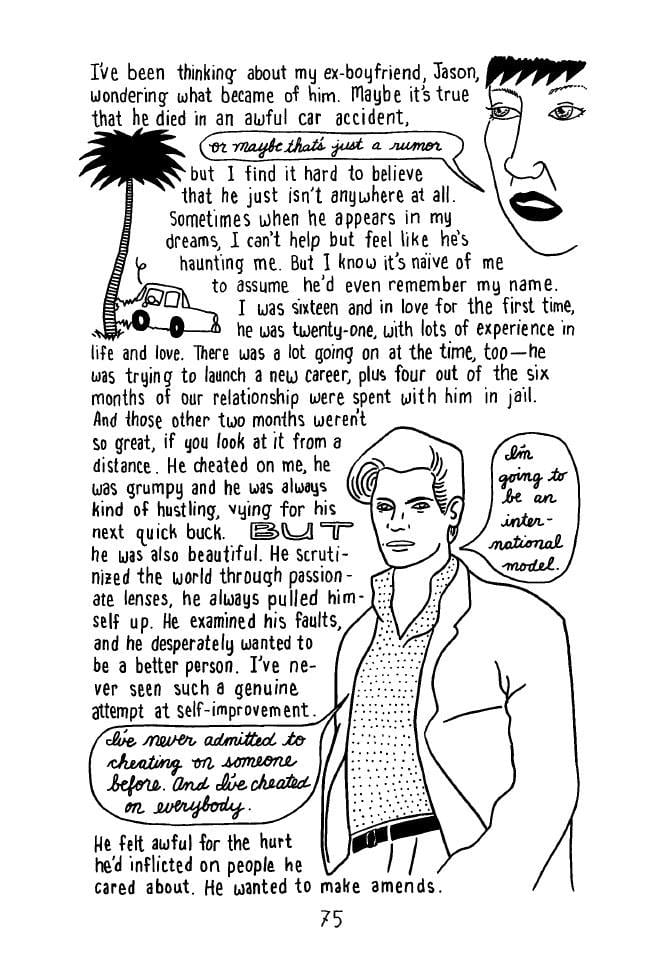

If compactness characterizes most of the stories in Dragon’s Breath, MariNaomi’s versatility as a cartoonist distinguishes the larger collection. She changes her approach to suit the requirements of each story, so the book’s pieces don’t read as repetitive despite recurring themes of alienation and romantic frustration. In “Gone”, MariNaomi surrounds scenes from a tumultuous early relationship with walls of hand-lettered text, highlighting certain frantic events and suggesting the tenacity of old memories. “When You’re Young”, which immediately follows “Gone”, features an anecdote from a similar era, of a friendship and a hoped-for romance with a coworker. As with her approach in “Gone”, MariNaomi frequently forgoes panel borders, relying on readers to follow a sequence through its arrangement on the page. But the layout of “When You’re Young” is more spacious, and fittingly so; MariNaomi also underplays the emotional beats in this story, giving readers more interpretive latitude than in “Gone”. When readers take a pair of stories like these together, Dragon’s Breath also hints at the fluid nature of how we recall our lives.

Certain inconsistencies within the stories of Dragon’s Breath do hamper a few pieces. In “He Sees You When You’re Sleeping”, the likeness of a young MariNaomi changes enough, beat by beat, to distract from the Christmastime anecdote being told. More common than these comics, though, are stories that stand out for their formal boldness. Even in the middle of some fairly linear narratives, MariNaomi includes pages that approach abstraction.

“What’s New Pussycat?”, an elliptical piece about the suicide of an acquaintance, delivers information sparingly. As a bridge between a scene dramatizing her last interaction with the acquaintance and the scene in which she learns of his death, MariNaomi provides the spread above: a handful of lines at resembling a splash, then the image of her likeness leaving a bar. These pages and others like them offer a complex yet sparse (and easily navigable) read—“What’s New Pussycat?” holds together tonally when read straight through and becomes even more cohesive when recalled or paged back through.

A similar piece, “A Stranger’s House,” gives readers not merely fragments of scenes but also fragments of figures. The story depicts MariNaomi’s unease while accompanying a friend to a sketchy nude modeling gig, creating tension with clear linework and the fewest possible lines. When the photographer first opens his door, we first see his glasses, nose, and beard, and then an isolated hand farther down the page. This is minimalism with purpose—the reader is immediately adrift. Though MariNaomi relies on text narration in many strips, sometimes multiple paragraphs at a time—and sometimes to strong effect, as well—“A Stranger’s House” forgoes that device and still creates a clear impression of her subjectivity in a fraught moment. It is an excellent piece of cartooning, and Dragon’s Breath includes many like it.