Aisha Franz's faces are an architectural marvel. Their features bunch up in the center of great round white circle heads crowned with hair that looks sculpted from clay. They're bookended by apple cheeks drawn with a perpetual blush rendered as circular gray scribbles, as though a physical ordeal or an uncomfortable emotion were always only scant seconds in their past. Eyebrows, wrinkles, creases, and smile lines push the eye toward the beady eyes and pug noses they ring. (The look is very Cabbage Patch Kids, but there's a reason those weird-looking things made millions.) They broadcast emotion from the center of the head like a spotlight focused down into a laser -- curiosity and confusion, peevishness and puckishness, boredom and loneliness and anger and, very occasionally, satisfaction and delight. In a book where Franz's all-pencil style -- the lack of inks and the deliberately boxy and rudimentary props and backgrounds suggesting a casual, tossed-off approach completely belied by Franz's obvious control of this aesthetic -- works very well, those faces work best of all.

The story is another matter. Earthling tells the not-quite-multigenerational tale of a suburban mother and her two daughters -- one on the cusp of puberty, the other of college. The book derives its title from the storyline of the younger daughter, who encounters and attempts to befriend an alien visitor she hides in the toy chest in her room. But it's equally concerned with her older sister, who's negotiating the needs of an estranged best friend, a physically eager but emotionally aloof suitor, and an absent father whose scheduled return is impending; and with their mother, who alternately seeks to discipline and connect with them while pondering a turning point in her own past. None are happy; all deal with their unhappiness alone. That's the only choice allowed them in the book's closed emotional system. Franz casts every supporting character as mean, manipulative, or oblivious. She paints her protagonists with a similar palette, or at least portrays them as so fixated on their own difficulties that they are useless to one another. Thus the storytelling deck is stacked against each to such a degree that we are forced to come to the same conclusions they do: no one understands them, the situation is hopeless, and only rash renunciations of responsibility or intercession by a well-timed savior can liberate them. Perhaps inadvertently, Earthling teases out the undercurrent of narcissism that those of us who suffer from depression often suspect, and fear, helps fuel those gray-pencil periods in our lives, but only to reinforce it.

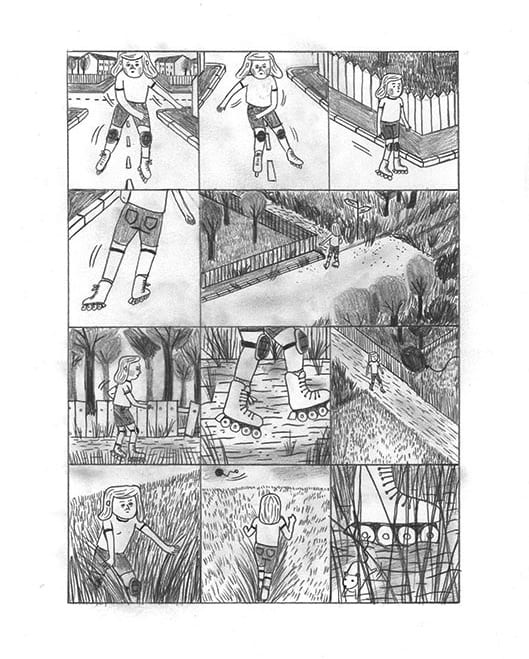

The tone is set from the start, as Mädchen, the younger daughter, spots a balloon with a note attached to its string floating past her townhouse window. Grinning, she straps on roller skates and glides through the suburban streets, eventually catching up with the balloon in a nearby field. But it pops, and the note reads only, "Whoever reads this is stupid!" Sad trombone. Her interactions with others largely continue in this vein. Her nameless friends make ribald sex jokes she laughs at without liking or understanding. Her mother chastises her for mild infractions like locking herself out of the house or wearing shoes indoors, her ignorance of Mädchen's extraterrestrial companion total and pointed. Her older sister, also oblivious to the alien who at one point is hiding in the shower while she urinates, imparts look-kid-I'll-tell-it-to-you-straight advice about love, sex, and their father that Mädchen is clearly in no emotional position to process; like her mother, she's too focused on demonstrating her particular brand of authority to worry about the receptivity of the audience.

The older sister's own interactions follow the same pattern. She's begun seeing "the hottest guy in town," but he's a dullard whose interest in her is clearly, exclusively, passionlessly sexual. In a bit of too-neat visual shorthand, he never takes off his sunglasses, even when she goes down on him -- a perfunctory, unreciprocated sex act that, naturally, Mädchen witnesses through a keyhole. She rekindles an old friendship, but that's mostly just to fill a gap in an afternoon when the dude ditches her. In a fantasy sequence where the pair regress to childhood and cavort in a fairy-tale wonderland, she seethes with resentment as the magical woodland creatures flock to her friend instead of to her and the cigarettes she tries to smoke turn out to be candy instead. She borrows the friend's bike and carelessly neglects to return it. She plans a vacation with the dude, only to discover he was seeing her friend behind her back anyway. Her conversations with her mother are exclusively hostile, centered mostly on ostentatiously rejecting a relationship with her father. She rubs his philandering, and her mother's lassitude, in her mom's face at the dinner table.

Unsurprisingly, given the opprobrium typically reserved for parents in comics of this genre, the mother, Doris, has it the worst. Unlike her daughters, who pursue secret plans and hoped-for assignations, she has no present-day narrative to speak of. Compare their initial scenes: Mädchen chases a balloon and meets an alien she hides in the house; her sister goes on a date with a hunk; Doris picks up dry-cleaning. The owner of the store stares at her, mute and implacable, through big round glasses that blot out her eyes; a little girl who's presumably her daughter fiddles with a Rubik's cube, gazes at her cryptically, then disappears. (I don't want to use the i-word, but it's difficult not to.) Two young, pretty women brush past her on the sidewalk outside, "BLAH BLAH BLAH BLAH"ing all the way; "Why do I always have to be the one who steps aside?" Doris muses, fuming. Why indeed. We subsequently learn, through memories and the is-it-magic-realism-or-is-it-a-hallucination intervention of a more glamorous and successful Doris from an alternate timeline, that Doris traces all her woes back to one day in college where she went to a different grocery store than her usual one and bumped into the boy who would knock her up, marry her, and by the time of the story largely abandon her and their daughters. She wishes she'd never set foot in that store. She remembers wondering if she should have gotten an abortion. She does this as she cooks a thankless dinner for her daughters, so that we can't help but wonder it too.

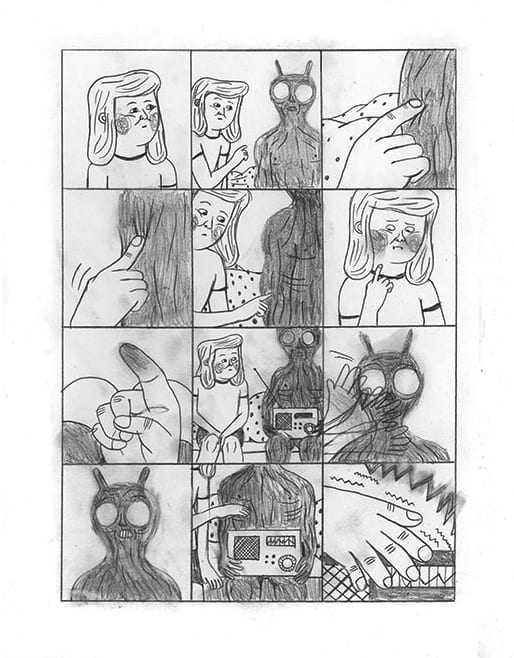

In the end, each member of the family is offered an escape of some kind, but each of those escapes is fruit of a poisoned tree. Mädchen had responded to the presence of the alien -- an excellent character design somewhere between an anatomical model, an alien Gray, and the rabbit from Donnie Darko -- by testing out the rituals of romance and sexuality she'd begun to pick up from her sister, her friends, and the TV. The alien is unresponsive, save in an uncomfortably erotic dream in which he and his people abduct Mädchen in order to teach her how to "do it." When she awakes, he's gone, but another balloon drifts by and lands in a crop circle implied to be the takeoff point of an alien craft. There she meets a boy her own age, presumably having weathered a similar encounter with an ET. But just when it seems like she might have a shot at making an honest emotional connection with a peer who shares her secret, a cutaway to an alien craft reveals their meeting as further manipulation by the visitor, whose motives are unclear and seemingly less than benevolent. But even with his blank-eyed demeanor and lack of speech he's only barely less capable of genuine human connection than the actual humans.

Mädchen's sister finds her ostensible reprieve closer to home. Chasing a runaway white rabbit (mmhm) who is carted around like a baby by an angry-looking woman in another magic-realist flourish, she stumbles across her friend and "boyfriend" making out (on a swingset, to make the loss of innocence even clearer). She runs away and weeps, only to be spotted by her deadbeat dad, who's returned to town from what she previously called "a mistress trip" in order to spite her mother so that he can take the daughters on vacation with him. It was this vacation she'd sought to dodge by making conflicting plans with the dude. But now she accepts both his ride back to their house, and his compliments for how good an old pair of sunglasses, which she'd begun wearing in seeming imitation of both the problematic men in her life, look on her. Yet at no point in this final scene do we ever see the father's face. He's just a voice emerging from a boxy car -- just as the alien's one word of speech, "Hello," emerges from a boxy radio -- and a means of getting from point A to point B. If we are to take this visual cue at (no-)face value, the prodigal father has not really returned.

Doris makes the cleanest getaway, or at least so it appears. Though it seemed as though her first genuinely pleasant interaction with one of her daughters -- she smilingly indulges Mädchen's "imagination" about aliens with the revelation that UFO sightings were once common enough in their area to make the news -- she winds up having a rage blackout in which she trashes their home. She is then beckoned by Bizarro Doris to follow her into the television screen, where she can live the life she always wanted. Doris's finger hovers over the remote. Cut to the next morning, as her daughters eat breakfast with no Doris in sight; they assume she went to the store. Instead, we see her as she was on that fateful day in college, deciding which grocery store to enter. She has a shot at total liberation, but of course this is also a total abdication of the daughters who need her love and support, potentially right down to their very existence.

That kind of question is a hard one, and hard questions are worth asking, but only if the answers given in return are honest. Parents and children can certainly be impediments to one another's growth and happiness, and that deserves unflinching exploration. (Though I'm less sympathetic to parents in these scenarios, since parenting their children is their job, not the other way around.) But in refusing to acknowledge or depict any compensatory value in relationships that are not wholly ideal, Earthling flinches. Responsibility and caregiving are not inherently the death of joy and self-actualization, but Doris's story is presented in such a way as to allow for no other conclusion. If everything about her life is so shitty, all the time, abandoning it is not just attractive but narratively insurmountable.

At the same time, the book's three-story structure means that even as her drive to vaporize her own life is unduly valorized, her neglect in the here and now is unfairly pilloried. Her conduct toward her daughters is uniformly phony and ghoulish, with little effort made to understand or humanize. Watching and listening to her, it's no wonder her older daughter disses and disobeys her at every turn, as she has nothing of value to impart. The daughter then repeats this pattern in her own interactions, pursuing a romantic relationship that alienates her from her friend and her own body, which she can only come to grips with through mimesis of her unscrupulous father. Indeed, with the exception of Mädchen, who is too young to be in a position of influence over anyone (even her own nascent sexuality is embodied by a literal alien invader), every character in the book is introduced in order to show how they just don't get what some other character is going through. It's psychology as epic fantasy, lone heroes beset by emotional orcs.

And it doesn't need to be this way. Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki's This One Summer is not a perfect book, but as time passes its achievements grow only more impressive. Though they're telling the story of an aimless teenage summer much like this one -- much like many, many ruminative alternative comics today -- the Tamakis refuse to let any of their characters exist simply to be impediments to others. Its two teenage-girl protagonists, their parents, an aunt and uncle, the local boy one of them crushes on, the girl he rejects when she gets pregnant: Each is a subject, not an object. Each is shown to make decisions based not on hands unfairly forced by people who've committed the unforgivable sin of failing to meet their unspoken emotional needs, but on a complex matrix of drives and desires and fears and external circumstances, valid and invalid, correct and mistaken, selfish and selfless. That takes a lot of work, but if the point of art about human relationships is to investigate rather than dictate, that work is worth it. I'm increasingly convinced that work is necessary.

Franz is a strong cartoonist, and since Earthling's original publication in German in 2011 she's gotten stronger. I've mentioned those faces and that alien design, but I could have gone on about how she cleans up her figure work for certain TV and fantasy sequences, or how seamlessly and breathlessly she conveys physical action as characters rush from street to street or room to room, or how the use of single-panel pages drives home certain emotional beats without ever feeling heavy-handed. (Her SF-infused short stories benefit from these strengths.) It's that kind of subtlety, curiosity, and innovation, the kind present in her pencils, that the story of Mädchen and her family -- or any story about people we wish not merely to recognize from their roles in "this kind of story" or the echoes of our own teenage resentments, but to know - requires to work.