Here is a book that presents itself as an antic comedy from the author of Goodnight Punpun, which may tempt the reader into thinking it a deliberate reversal, or even a course correction. Reading this interview with Inio Asano from 2014, around the time of the series' launch in Japan, will only encourage that notion: deeming the project "one hundred percent" an attempted diversion from reality, Asano summarizes Dead Dead Demon's Dededede Destruction as "about positive things that people want to see." Granted, in the same interview, Asano states that human society has entered its endgame, and that the paramount concern for people now is to discover how to live in the midst of a global downward spiral, so be aware that we're dealing with a slightly different idea of 'positive things' than otherwise expected.

The premise of the series is this. Not long ago, an enormous alien spacecraft appeared above Japan, causing some amount of property damage and loss of life as it maneuvered itself into a low hover. A perhaps more serious incident subsequently occurred when United States military aid resulted in the irradiation of Tokyo via an advanced weapon, but people don't talk about that so much because the effects of A-rays aren't scientifically proven, and anyway the presence of aliens has supplied a new excuse for profitable militarization in Japan, to say nothing of the political benefits of patriotism. On the day of the invasion -- which, doing the math from this series' 2014 serial debut in Japan, places it in 2011, conspicuously the same year as the Tōhoku earthquake and the resultant Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster -- young Kadode Koyama's father was either killed or took the opportunity to abandon his family. Three years later, Kadode's mom, a political radical, is a hypochondriac mess of anxiety who wants the nearly-graduated teen Kadode to join her and her boyfriend off the grid in a clean-living commune. Kadode doesn't want to go; she mostly just wants to hang out with her pal Oran, a manic girl with massive twintails who's deeply invested in online first-person shooter video games, but not because she loves warfare. In fact, Oran is disgusted by the hypocrisy and superficiality of society, so she trains herself for domination in a coming world where humankind is rightly brought low: standing tall at the bottom of the drain.

If you've heard anything about Dead Dead Demon's Dededede Destruction, you've heard that it's not an SF suspense serial, but a slice-of-life series focused intently on the everyday doings of Kadode and Oran; Kadode is the "Demon" of the title, courtesy of a linguistic pun complicated enough that Asano has the character explain it on-page, saving translator John Werry some grief. Asano's stated inspirations for the series include Hikaru Nakamura's Saint Young Men -- an episodic comedy finding Jesus Christ and Gautama Buddha as urban roommates involved in light hijinx -- and K-On!, a four-panel gag manga-turned-hit anime series about cute high school girls in a student music club. And, if you know anything about Japanese commercial nerd entertainment, mention of K-On! has instantly thrown open the doors to all manner of comics and cartoons in which the consumer is invited to gawk over the affairs of young girls; the most respectable of these to western comic book readers may be Kiyohiko Azuma's Azumanga Daioh, but projects tend to come in varying amounts of lewdness, for the pleasure of a frequently-assumed-to-be-male-heterosexual audience and the eager exchange of their dollars.

Of course, none of this is to say that the only potential result of work like this is guys slobbering over drawings of teenagers, but it does draw attention to some of the particulars of Asano's story. What does Kadode do in this book? A pretty large portion is devoted to a crush she has on a male teacher, which plays out as the kind of situation that creeps up somewhere near the line of inappropriate -- she hangs out in his apartment for a while, delivering some self-aware dialogue about how sketchy this all is -- but does not cross into anything physical, though the potential for such is left hanging tantalizingly in the air. "I think I'm gonna watch some porn," muses the teacher as Kadode leaves to rejoin Oran, the friend to whom her loyalty belongs. Another chapter concerns, in significant part, Kadode's relationship with Oran's older brother, a fat, anti-social computer nerd type whom she promised to marry as a little girl; it is playfully suggested that Kadode likes that he is fat, so that she isn't at risk of becoming attracted to him, and thereby falling prey to making any serious decisions about her future.

You can hopefully tell from my descriptions that Asano uses these scenarios to tease out Kadode's ambivalence over where her life is going, which is a theme that runs through all of his translated body of work. At the same time, and unlike with even the comparatively melodramatic devices of a book like Solanin, it is difficult here to avoid the way these rather shopworn vignettes also function as a consumer fantasy. Big Comic Spirits, the weekly magazine in which this comic is irregularly serialized, is the sort of publication that puts photos of girls in bikinis on the cover to catch the eye of weary men, and gee: wouldn't it be fun to be a teacher and have a cute girl crush on you? Or have a cute girl ask to marry you when you're young and still hang around, kindly, when you're older and fat? Isn't it nice, really, to just watch cute girls being cute and discussing things like going on dates with classmates and nerdy things you've heard of like online gaming and boys' love comics, and don't you feel a certain happy glow from that?

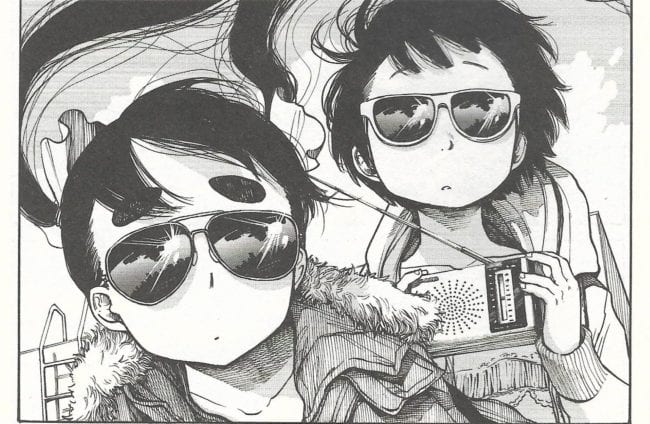

This toeing of the line is also expressed in the way Asano draws - and, while I don't find many of the situations depicted in this comic to be so interesting, I very much like the means of depiction. Goodnight Punpun (which, in the interest of full disclosure, I never did finish reading) saw Asano's art reach dizzying, airless heights of auto-critical realism, in which very gestural or deliberately super-stiff elements would be introduced into a suffocating schema to puzzling or upsetting or contemplative effect. Dead Dead Demon's Dededede Destruction, in contrast, is an energetically *cartooned* work, in which the character of the lines say as much as the content of the drawing, which is something I happen to prefer. Asano's putty-like characters droop and wobble on bow legs, arms flailing as they run. Several men in the story seem spooned together from mashed potatoes, facial expressions reduced to tiny circles and twinkly dabs of ink. At two points in this volume, the comic transforms into a homage to Doraemon creators Fujiko Fujio, the style of whom Asano emulates with terrific acuity. The backgrounds are done with the assistance of three other artists -- Satsuki Sato, Ran Atsumori, and "Buuko" -- but their realistic nature is not so photographic as with some of Asano's more recent works, and they blend well with Asano's character drawings, except when they are not meant to.

Always, there is the spaceship. Sometimes it stars in lavish splashes and double-page spreads, but often it merely sits there in the background of panels, unmemorable to the characters, but inescapable. Nobody can prove they've actually seen an alien. All the spaceship ever seems to do is release the occasional smaller saucer, which the SDF sometimes shoots down for another day's heroism, although the crafts seem just as liable to crash on their own. And, sometimes, the big ship emits eerie sounds, portrayed as jutting curls of black ink, like emissaries from the realistic world of the ship to the cartoon setting of humankind; it is a gigantic floating metaphor, not just in the literary sense of a still invader looming over young people on the cusp of life changes, but in purely 'comics' terms of drawing quality.

The girls, pertinently, are drawn very young. Given the context of the story, they have to be 17 or 18 years old -- Oran even drives a car! -- but Asano very conspicuously declines to draw them any differently in present-day scenes or flashbacks to three years ago, when the aliens arrived and the characters were younger. In fact, very few of the students depicted throughout the comic, boys or girls, ever rise taller than shoulder-height to any adult in the story. This naturally serves to make them all cuter, but also emphasizes their vulnerability, their hesitancy about adulthood - which, again, could just make them all the more efficient as commercial fetish objects. Images such as these can prompt empathy, identification, desire - and these qualities can become more pronounced in the context of simple everyday scenarios, as we find here.

But Asano has a more specific everyday going on than usual.

Kadode and Oran are both on the side of the aliens. Kadode, who doesn't have much to look forward to in her adult life, was hoping the aliens would destroy everything, and expresses a profound, Demonic disgust toward the caprice and mob mentality of human unity. Oran is quick with theories about the surveillance state, about U.S. conspiracies and the military-industrial complex, eager for the day this shit society collapses. Asano's comedy is at its most trenchant when depicting the media surroundings, sappy memorials and political trolling sharing online space with porny news links and listicles. A television spokesman boasts of the eco-friendly nature of a new "clean weapon for urban warfare." Kadode gets a note from her mom that the Okinawan vegetables she left for supper are not contaminated; she plays an online combat game, scrolls through notifications about recent martial self-defense actions on her phone, then looks at some funny memes before falling asleep. Black metal glitters in the night sky, a titanic justification. Is this Shinzō Abe's Japan?

If we are to look at the interesting characteristics of this comic, we should look less at what the characters are doing, and more to the core of what they do. It is easy to present characters who are sort of isolated, and who comfort themselves with nerdy things, but Asano at least gives these characters a palpable reason for withdrawing. To return to that interview I linked up top, it is striking to hear Asano coach his desire to create a more widely appealing comic in terms of helping his series' magazine home sell: "I’ve gotta make sure we don’t lose Big Comic Spirits," which, while pleasingly unwholesome, and willing to run a long, depressing comic like Goodnight Punpun, is also distinct from nerd-focused magazines by superfans for superfans, which create a hermetic and trope-driven experience. "The general seinen magazines, on the other hand, deal with subject matter that’s actually connected to society, so you don’t have to be a manga enthusiast to enjoy them." I'm writing this two days after the last extremely prominent run of U.S. bombing assistance - completely necessary, we are assured. Look at the characters in this comic, Asano invites us, and then look out the window and see the spaceship for yourself.