The naïve soul, now lost to history, who had the chutzpah to put breath to the thought "don’t judge a book by its cover," never read comics. To wit, the white cat on the cover of Teddy Goldenberg’s City Crime Comics. Said feline marks the rare occurrence when a cat’s face is also the “cat’s ass”. The animal’s aspect appears both quizzical and mendacious, which anyone familiar with the day-to-day life of a cat will clock as common to the species. Like the reader, this cat, by no fault of its own, has found itself in a peculiar predicament. Teddy Goldenberg captures the moment when a Dick Tracy simulacrum has received (perhaps) a call on his two-way wrist TV (not visible) while in attendance at an autopsy al fresco for Professor X. To the left of faux-Tracy (and X) and on the opposite side of the frame from the cat, a shadowy figure lurks in a doorway. This picture occupies three-fourths of the cover and is perched over the title, white letters over black. Below this no-frills title card is an image of a woman’s face and the back of a man’s head; the couple appear to be in some sort of awkward or perhaps amorous embrace that could be a hug as easily as the Heimlich. Like the silhouette in the doorway of the image at the top of the page, an unattended pot of something brown has boiled over on the portside and made a mess on the floor and stove. Given these circumstances, the cat’s countenance appears more than justified.

City Crime Comics contains 21 short comic strips awash in such absurdism and audacity. A space in which the word “splendiferous” is used irony-free to describe a car ride in the country, synthetic rubber tongues cover houses, and a couple of buckets and more than one statue have equal bearing as plot points. Goldenberg’s Golden Age affectations are only that; he’s no more interested in “crime” or “dicks” than he is in aping Chester Gould. Cartoonists draw and this is how Goldenberg has chosen to do so. What his drawings and color palette accomplish adds to the absurdism by grounding it in a comic reality. What better place for a “comic” to exist, yes? City Crime Comics is so idiosyncratic, so personal and so screwy—a slow-speed drive-by of a highway automobile accident of primary colors and twisted thoughts—the reader can’t look away.

The phrase “it’s so surreal” has become shorthand to describe the indescribable. Dalí would be doing backflips in his crypt if he knew how often surrealism was passed off as mainstream meaninglessness or silliness. City Crime Comics earns its surrealism, because like its Golden Age look, it’s a dodge, a visual feint - a treachery of images to be for sure. How else could Goldenberg sell his romance-cum-crime stories without something for the reader to recognize and (at least try to) latch onto. How else to explain(?) a story like “The Public Sector” wherein a curly-haired, red-headed woman (a Lucille Ball type, but not funny and likely conversant in German) appears to be in a movie. Soon, this steno pool stand-in picks up the phone in the office of a Mr. Shamwood and follows a faceless caller’s unheard directions, which put her in the backseat of a cab driven by a nervous, sweaty driver across town to attend some sort of public presentation. The presenter, who could be FBI, CIA or JFK, greets his audience of “caretakers, firefighters, fraud investigators, inspectors, pump monkeys and tar pushers.” Out of this collection of the great unwashed, he chooses the protagonist whom he calls “Fräulein Klum” to “go in the well.” Which, literally, finds the fräulein strapped into a contraption that lowers her into a stone well on the stage. She descends, and then is pulled back out of this reverse Lazarus Pit to reveal she’s become a cement statue. The Frau Klum effigy is placed outside the steps of the building. In the final panel the FBI-CIA-JFK-looking-dude comforts the cab driver.

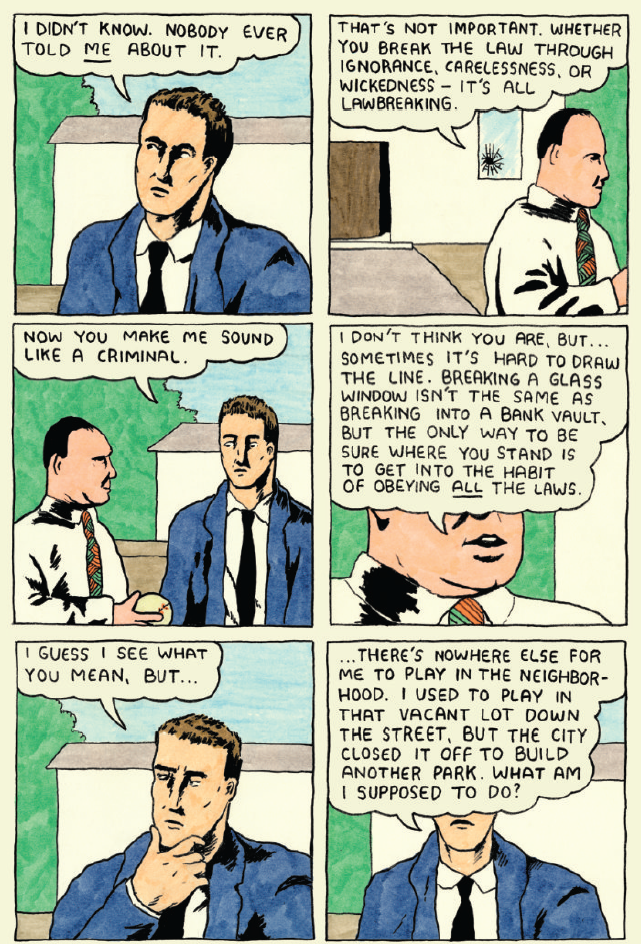

Goldenberg’s lack of kowtowing to logic comes out in his playfulness and total lack of preciousness about narrative or comic conventions. A man wearing a suitcoat and tie breaks his neighbor’s window with a baseball because there’s nowhere else for him to play, since the city closed the vacant lot to build another park. The homeowner explains the importance of “the law,” personal responsibility and the social contract to the suit jacket-wearing scofflaw. Each man's explanation is so long and each so absurd that their word balloons crowd out their faces. Chris Claremont should have tried to inject such humor into the endless equivocation in his many mutant comics in the '70s and '80s. Goldenberg’s City Crime Comics is a one-man abattoir where all the sacred cows are ground into hamburger and storytelling conventions clog the drains.

This artist vibrates on a singular wavelength. His lumpy bumpy figures abhor parks and nature, teach about trains, and take solace from being insured. These characters represent the bizarre nature of the everyday. As the absurdity of its numerous non sequiturs begin to pile up, City Crime Comics feels normal. After all, who hasn’t stumbled home from a late night drunk, come across a catatonic and a suspender-wearing tough in an alley, and found solace in a nearby church? Be honest! Goldenberg’s comics invoke a wonderland, a Baader–Meinhof phenomenon where white cats, like the Cheshire cat from that other wonderland, welcome the reader into a bizarre bazaar of luggage-less travelers, ill-fitting suits and conversational Dutch.