What’s the point of making art in a technological era? This question, and variations of it, make up the heart of Joseph Remnant’s first longform graphic narrative, Cartoon Clouds. Clouds follows freshly minted art school graduate Seth Fallon through insecurity, uncertainty, poverty, and the pretentious Cincinnati art scene. A small nexus of art grads trying to “make it” as serious artists in an increasingly pop-culturized contemporary market succeed to various degrees — or get stuck in the cogs of unrelenting capitalistic machinery. The tale focuses on the humdrum futility of this post-grad life and the very real choice perhaps all young adults must make: to either follow or abandon their idealistic dreams. What prevents Remnant’s narrative from becoming a rote run-of-the-mill coming-of-age tale is the caricatured portraits cropping up throughout the text of newly-divorced art professors, established but jaded artists, and culture-vulture branders. These character sketches speak to Fallon’s artistic sensibility: art is capable of capturing a side of people that they cannot see in themselves.

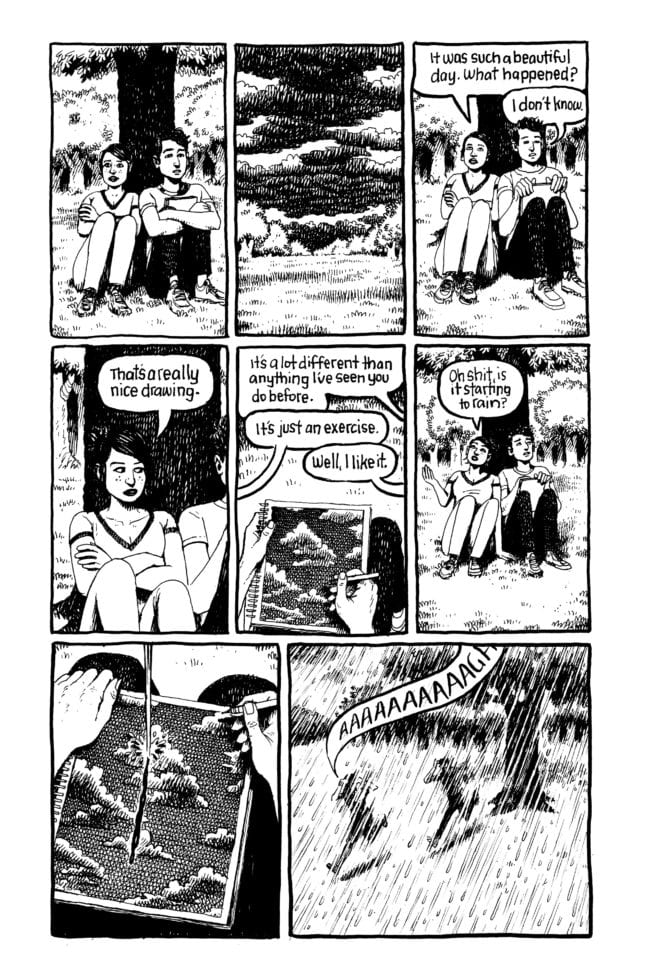

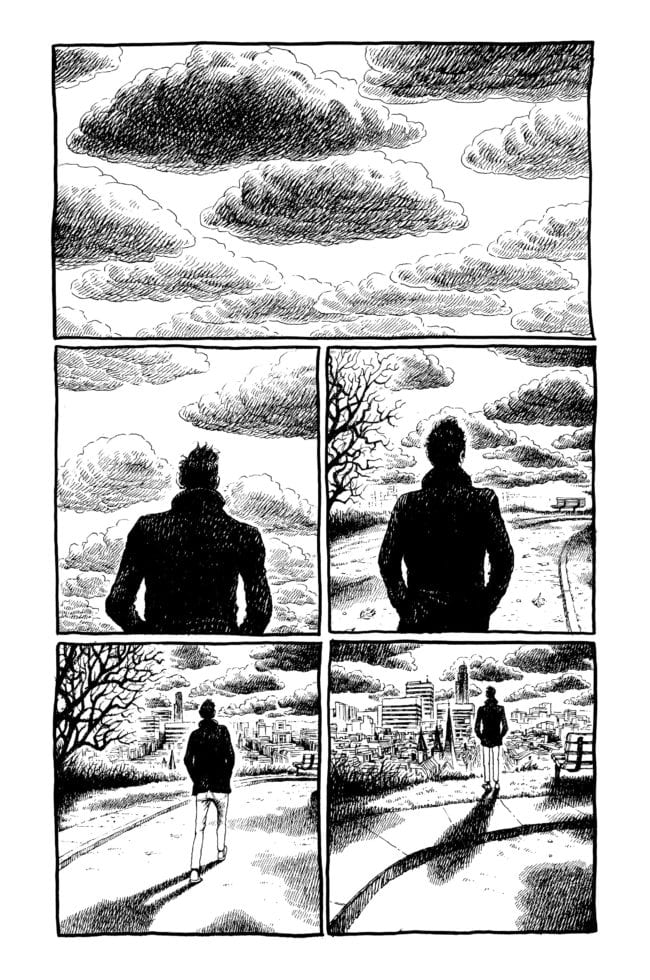

Though heavily ironic in tone, the graphic are tempered by a sense of idealism and hope. This is reflected in Remnant’s compositional style. Those familiar with Remnant’s work will recognize some of the same sensibility found in Harvey Pekar’s Cleveland. However, Clouds feels comparatively claustrophobic. The first half of the text is comprised mostly of talking heads, in panels that feel oppressively text heavy. Contrastingly, Remnant’s work shines most when such panels give way to silent sequences that free Fallon up and allow the reader into his personal artistic perspective. Whether the relentless ‘talking-head’ panels are a product of Remnant’s early work with a long form comic narrative, or intended to indicate the story world’s oppressive verbal criticism or otherwise idle chatter, is difficult to discern.

In Clouds, Remnant’s typically uncanny ability to capture a scene, an emotion, a character in a single image, as seen in his graphic work, is somewhat lacking. Panels feel repressively repetitive, with figures moving only slightly, and the close-quarters of the panels making the few changing backgrounds inconsequential. Perhaps this mirrors Fallon’s limited vision on the immediate present, the immediate criticism of graduate professors, friends, and would-be employers, but it lends the graphic a stiff artistic style overall, whose only respite is broken by Fallon’s imaginative forays into his notebook sketching the broader landscapes before him. Perhaps this compositional tension answers the question posed to Fallon at the outset of the text: what’s the point of making art in a technological era? The book seems to champion making art, period, no matter how volatile the surrounding culture, fickle the reception, or seemingly simplistic its style. It says that, as Charles Bukowski once suggested, the only reason anyone should make art is if they can’t not make art.