There is a certain book in Italian comics history considered to be the first graphic novel of our modern age, one that came before even The Ballad of the Salt Sea by Hugo Pratt. That first story of the character Corto Maltese was serialized between 1967 and 1969, while La rivolta dei racchi ("The Revolt of the Ugly”) by Guido Buzzelli was published in 1967 as a standalone piece - more of a graphic novel than Pratt's, which is part of a longer saga. Unfortunately, La rivolta dei racchi is not included in the book we are talking about here, the first English-language collection of the Michelangelo, the Goya of Italian comics, recently published by Floating World. It will appear in vol. 3, and may require a whole essay for itself. La rivolta dei Racchi had a troubled editorial history; and its author, in his brief life of 64 years, had always been quite an outsider - an artist impossible to put inside a single box.

Born in Rome in 1927, Buzzelli started his career in comics at the end of the '40s. Like other Italian comic artists active in the '50s and '60s, he worked at times for the British publisher Fleetway, providing art for their long series of war-themed magazines. He met with little success in the popular genres, and turned to fine art painting; it was mostly thanks to the French artist Georges Wolinski, who discovered La rivolta dei Racchi at the end of the '60s, that Buzzelli enjoyed a breakthrough in praise and appreciation, first in France and belatedly in Italy. He is today revered for solo comics that in their time were quite bold and unusual.

Many of these stories featured him as a character, or at least his physical persona as an actor in roles beyond autobiography; we might describe it as a kind of meditative surreal autofiction. He did not just let a character borrow his physique - a slim build and a bold face covered by a black beard, dotted with two sparkling and sad eyes. Rather, Buzzelli was part of his stories, struggling with and for his characters. This approach to comics is probably easier to understand now than at the time he was active. His comics have aged even better than those of Andrea Pazienza, another iconic Italian comic artist of the past who put his own face and experiences on the page.

What we have in this gorgeous 8.5" x 11" collection, the first of three, are the stories “The Labyrinth” (1970) and “Zil Zelub” (1972). Spell that carefully: z-i-l-z-e-l-u-b. Yes, I see some hands raised, you've noticed the trick: the title is an anagram of the author’s last name, Buzzelli. This is not just a game for its own sake; the reason for the title becomes clear by reading the story, which sees a violin player who looks exactly like Buzzelli falling apart piece by piece, limb by suddenly autonomous limb, on a desperate run for his life, seeking help from friends and doctors. (It reminds me a little of Tsuge's "Nejishiki," where a man wanders a strange town in search of treatment for a wound.) There will be more comics where Buzzelli uses his own body and mind as a narrative tool, dismembering himself before the reader.

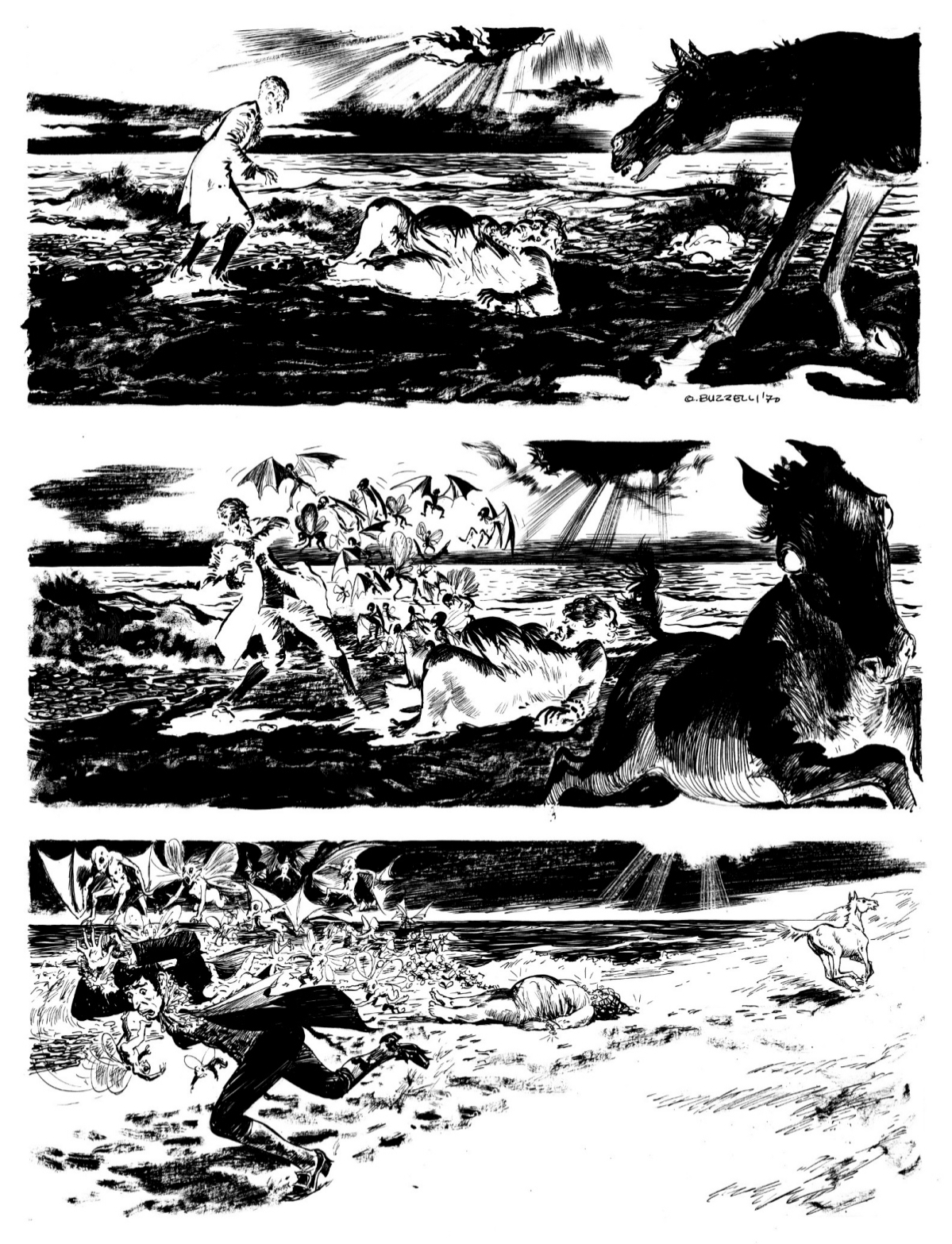

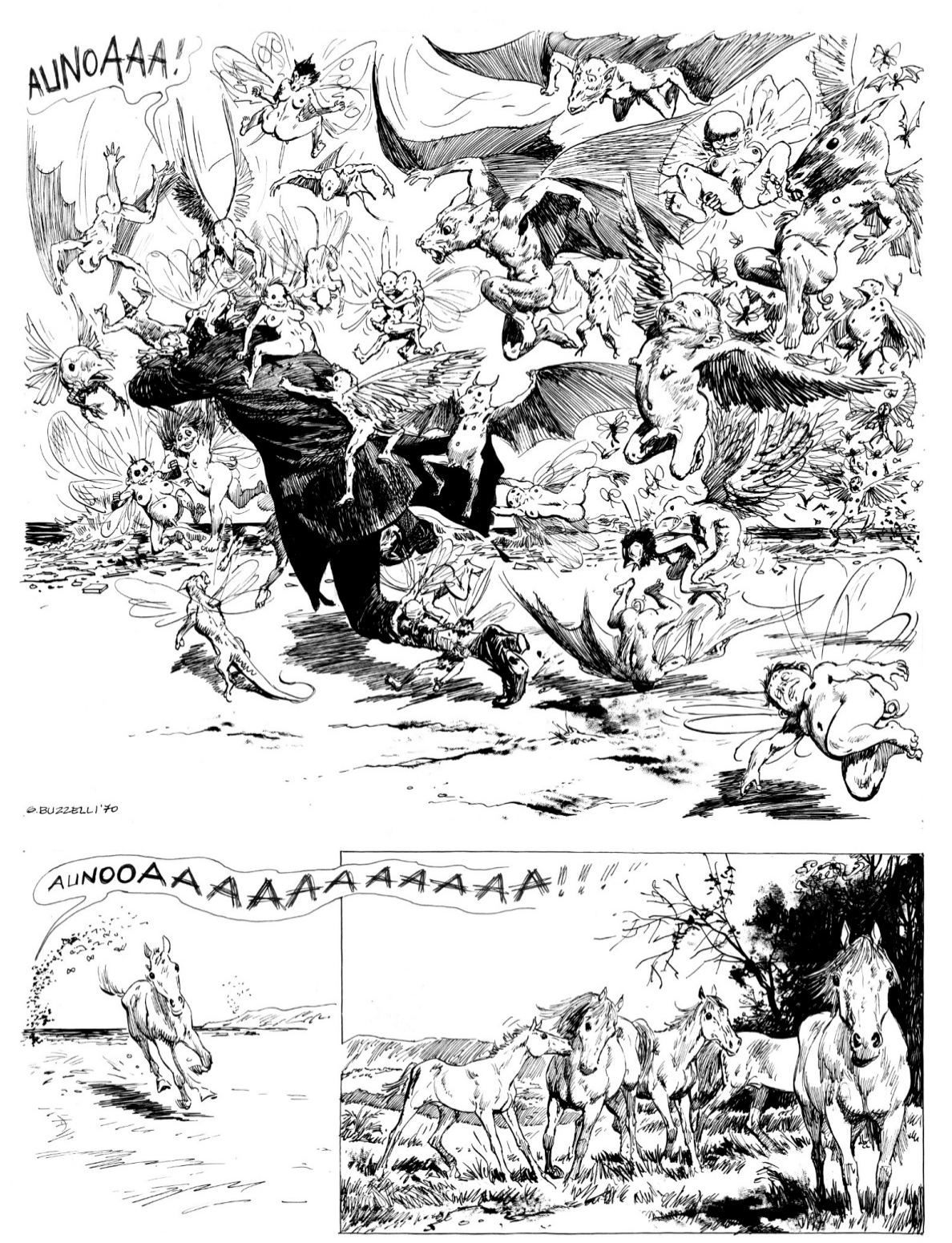

“The Labyrinth” is even more intricate and thought-provoking. Like a hapless man out of a Franz Kafka story, the main character abruptly wakes up in a ruined world, and his first words are "My house!!! My car!!! My bank account!!!" Such clear criticism of the consumerism of his time suggests comparison to the novels of Guido Morselli—an Italian writer who was misunderstood at the time he was alive, rediscovered and revalued only in recent years—who wrote grotesque and desperately satirical dystopian novels. (I highly recommend his Dissipatio H.G., which was published in English by New York Review Books in 2020.) The unsummarizable journey that ensues in “The Labyrinth” might be called an adventure, a thriller, a comedy, but the heart of Buzzelli’s storytelling has nothing to do with the genre definitions so important for the Italian comics market of his time, which cannot find a place in his exuberant production.

These two stories are grotesque, yet graphically virtuosic; one can sense the influence of the Italian art of the Renaissance alongside the avant-garde movements of the early 20th century, Cubism and Expressionism, in the juxtaposition of his images. These are the roots of his comics storytelling, along with the stream of consciousness of writers like James Joyce or Italo Svevo; the blending of all these ingredients produced something that was never seen before and rarely seen again. Buzzelli’s is not the same kind of speculative absurdity that came from his contemporaries in European comics like Moebius or Philippe Druillet; instead, he was focused on the mind of human beings and the role a person and an artist has in our ever-changing, ever-derailing society, vomiting out all his rage and anxieties. His work has the deeply imaginative power of a true visionary.

Buzzelli was not as prolific as other famous Italian cartoonists—Guido Crepax, Milo Manara, Dino Battaglia—but this perhaps makes him more accessible. In recent years, after seeing an exhibition of his works at the BilBOlbul festival in Bologna in 2018, I started collecting older editions of his books, and buying old magazines that contained his short stories. I enjoy trying to recreate the same feeling readers of older comics had at the time, rather than buying perfect recent editions, but that can be only be done with Buzzelli if one can read Italian or French. I have to admit Coconino Press in Italy did an amazing job collecting his work and giving it new life, and it is on their editions that this English book is based. I would easily consider it one of the best collections of old material published last year.