Jazz is right: this new effort of ‘poetry-comics’ from Nick Francis Potter reflects the musical idiom, especially in its modern incarnation, in ways both good and bad. Like jazz at its best, it has a loose improvisational feel that coalesces and coheres into something greater than its parts, and like jazz at its worst, it can feel like an insular language that seems impenetrable and even alienating to those not immersed in its techniques. Ranging from subtly inward-looking and contemplative to chaotic and filled with fiery emotion, Big Gorgeous Jazz Machine isn’t easy to read, and it doesn’t give readers an easy way in, but if they connect just right with its groove, they might find it rewarding in ways few other manifestations of the comics medium can achieve.

Aside from a six-page interview with the author at the end of the collection whose degree of interest will be entirely contingent on how much you liked the material, the book is broken into ten sections that progress along like variations on a base note. It gives the book both too much and too little credit to call it a ‘narrative’, but there is a sense of building, one section on another, like a quiet shift of modalities or an almost imperceptible change of chords. Interestingly, a 12-panel grid right before the contents page sets the table, demonstrating Potter’s visual style: a hectic combination of simple iconography and crudely complicated line.

The wordless prologue is one of the book’s most striking sections, and it provides as good a definition as you’ll get for the meaning of ‘poetry comics’; in it, faint lines in black and white grow, tussle, cluster, and expand against the boundaries of the panel before coalescing into an interior frame and collapsing back into a vaguely heart-shaped mass. It’s a surprising and dynamic introduction to the book, giving the impression of being animated on the page while allowing no definitive reading of what’s actually being seen.

“Vacationing”, one of my favorite sections of Big Gorgeous Jazz Machine, begins with a memorable opening line (“If a man in a white shirt and a tie catches on fire, and people – people being who they are – refuse to extinguish the flam, you’re on vacation”, a phrase I can’t help but hear in the tombstone voice of William S. Burroughs) and some of the most directly human images in the book, is as intense and explosive as its imagery. “Imaginary Houses” combines a captivating visual (of a constantly transmogrifying series of spaces, mounted on scaffolding to make it look like a mad bird reminiscent of Paul Klee’s Twittering Machine) with a far more expansive text. The latter is marred by its disjointed post-modern back-pocket surrealism, the kind of contemporary poetry that I have always struggled to relate to.

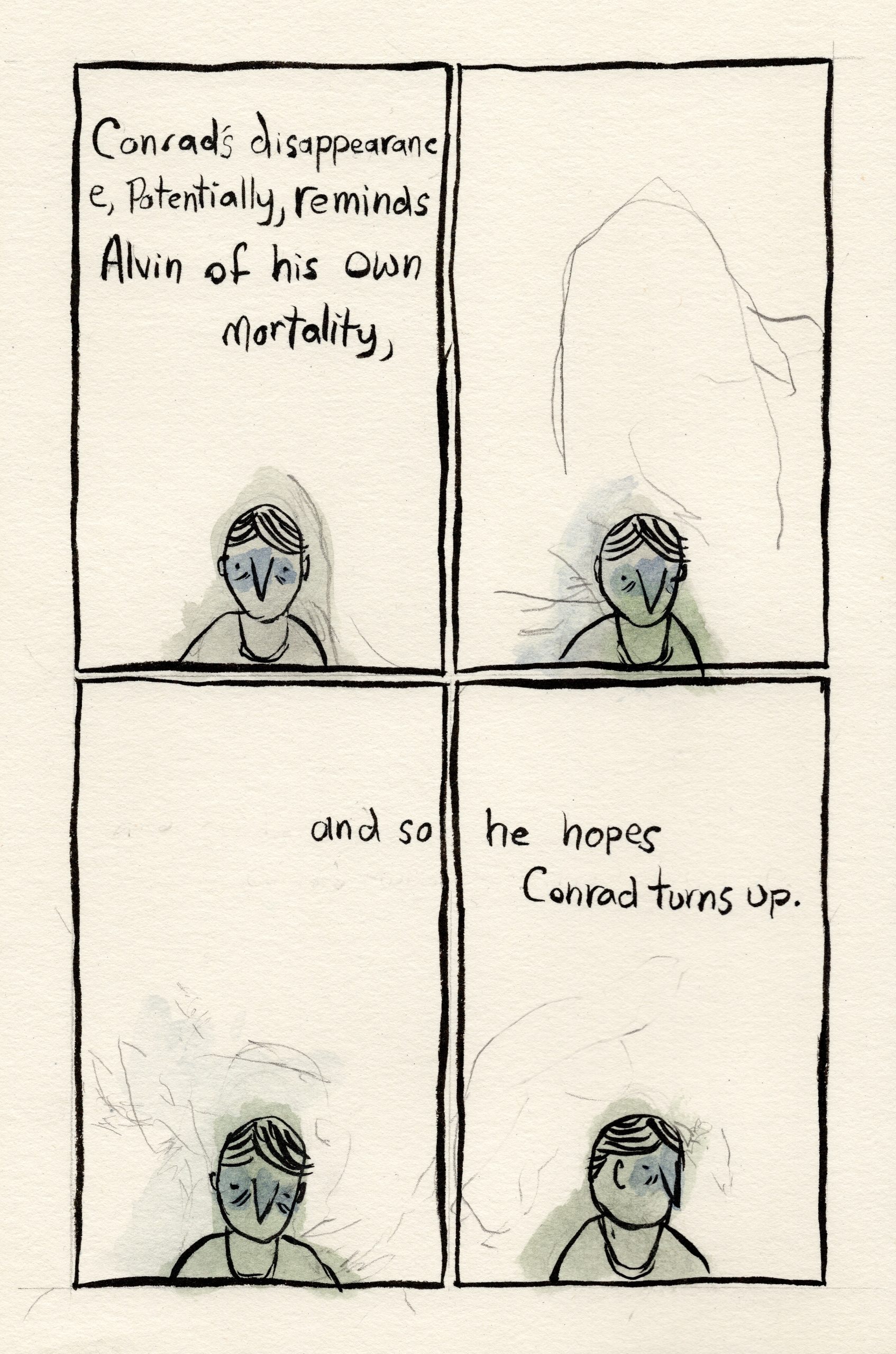

“Alvin Dillinger’s Brother” is another excellent installment (for all his daring in portraying the unreal, Potter is at his best when he gives us a recognizable human figure to surround with swirling chaos), repeating small variations on the theme of the central character while surrounding him with rough scrawls that reflect his psychological landscape. “Some Notes on Domestic Phenomena” is a series of lightly connected single-page vignettes around the theme of family and is more notable for its inventive use of color than its ability to craft a cohesive sense of meaning.

An interlude that minimally mirrors the prologue gives way to “Some Notes on Domestic Objects”, which seems even more vague and ethereal than its predecessor; it hints at hidden meaning and breakthroughs, but never quite connects thematically. The pink-and-red-tinted menace of “After the President” is as expressly political as the book gets, and oddly enough, at a time when gestures like fact-checking and rational debate seem especially futile, manages to be shockingly effective and appropriate. Saying Trump was “elected to wield magic” is both lovely poetry and a canny indictment of the erosion of ideological coherency in contemporary governance, and the art nicely reflects that emotional precision.

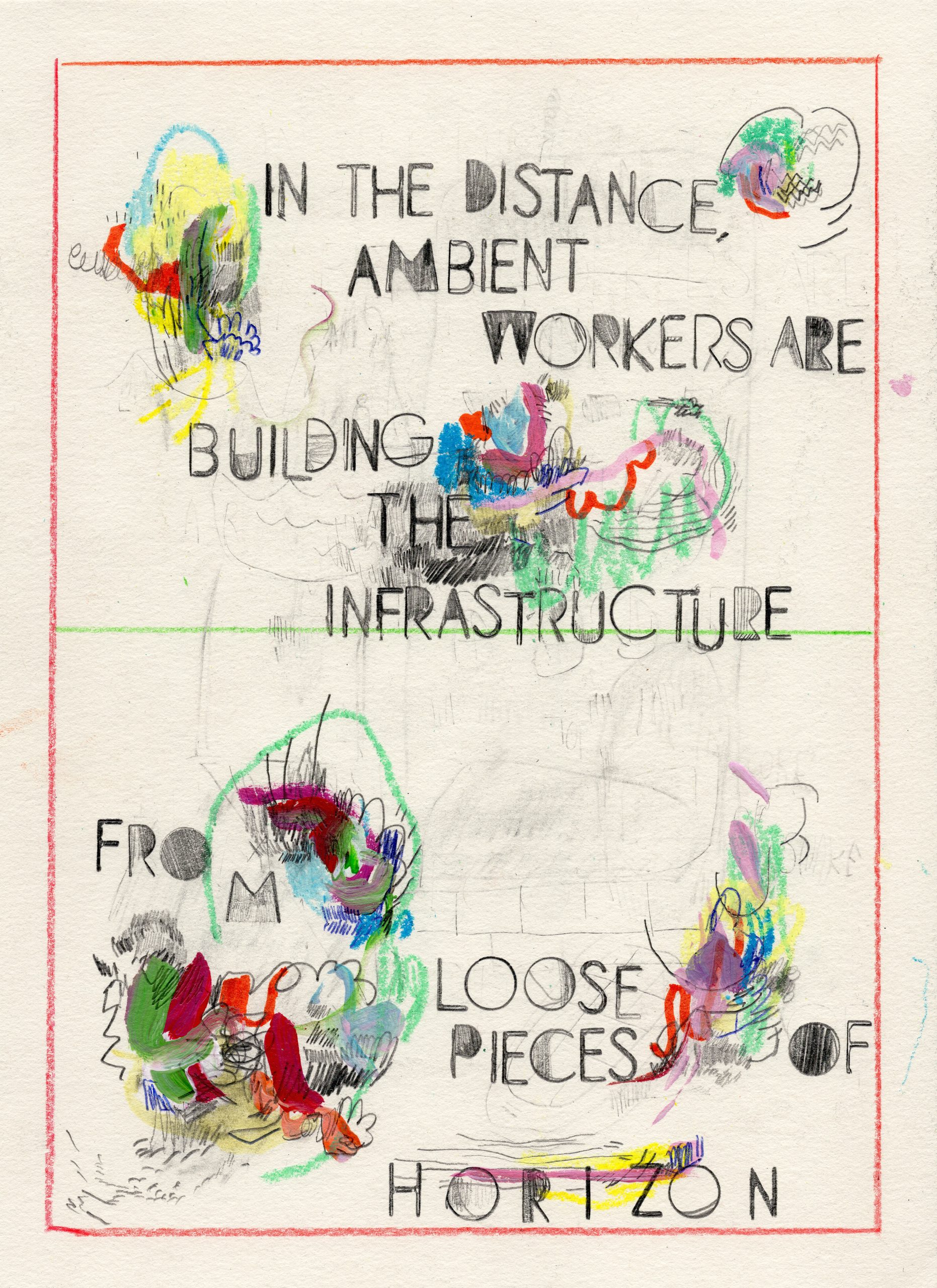

“Look Stop Have Haircut My Hair Maybe” makes about as much sense as its title and literally and figuratively comes across as refrigerator magnet poetry. “Ambient Day Labor”, on the other hand, is perhaps the best piece in the collection, featuring Potter’s stark lettering delivering an indictment of technocracy and alienation over images that invoke the direct opposite of those phenomena: an oozing, organic, frenzied mass of living tissue and industrial detritus, the wreckage of an old world pushing back against a new one. “After the Animals” ends the book (save for a familiarly-styled epilogue) with powerful words and images, forming a vague but terrifying vision of environmental catastrophe where grows bored and self-destructive in the ruins that it has created.

What, then, does it all mean? It’s poetry of the word and poetry of the image, and thus doubly elusive and doubly difficult to critique in any meaningful way. Recalling Eliot’s admonition that poetry is an arresting of the personality and the emotions rather than a loosing of them, I am struck by Potter’s ability to reign in the tumult he has created; but I am also frustrated at the times when he seems to fail in that effort and give up. I would not blame anyone who finds this book a morass of meaningless back-alley symbolism. The endless potential of so many contemporary artforms, from jazz to poetry to comics, allows for much work that does not reach out a hand to grasp or define a place to meet it halfway.

All told, Big Gorgeous Jazz Machine provides us with little to contemplate beyond what’s on the page, and that’s not always a good thing – but it’s not always a bad thing, either. Free jazz can be challenging or, worse, enervating, because it requires as much effort from the listener as it does from the performer – a deal to which most casual fans are not accustomed. I’m not willing to tell those fans that it will be worth the effort. But like free jazz, this book has elements which reward close attention and unspool deep emotion as well as elements that can frustrate and confuse. If you’re willing to make the bargain with Potter and give the book that attention, you may find the rewards of wandering out to the edges of its possibilities.