“Superheroes are real when they’re drawn in ink,” David Mazzucchelli declared at the end of a four-page strip serving as an afterword for a 2005 rerelease of Batman: Year One. I kept thinking about that strip while reading Batman: Creature of the Night, a book purchased in the wake of the tragic death of its artist, John Paul Leon - a man whose approach to putting the ink down would mark him as a Mazzucchelli guy even if neither artist had ever drawn Batman, and who turns in career-best work here.

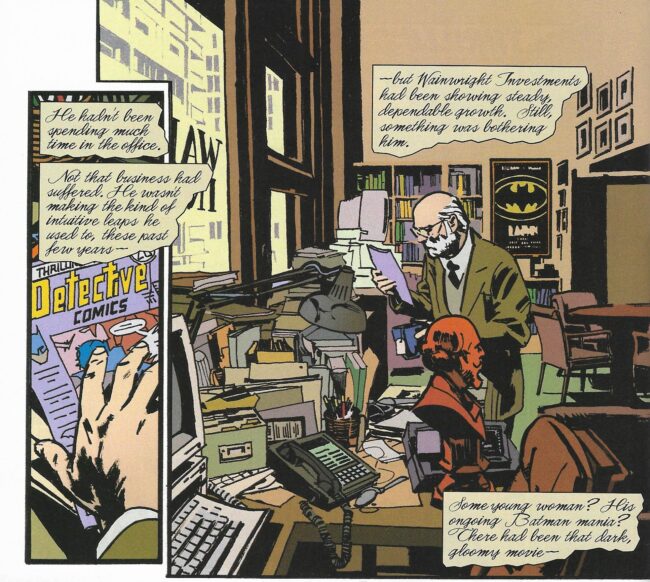

One of the first things that impresses is that Leon is coloring his own work. Like most comics artists, he benefits from a flat color treatment rather than the gradient-heavy over-modeled approach that became increasingly de rigueur within mainstream comics over the course of his career. While Leon has largely been in a position to have his work presented in a flattering way, due to a long professional relationship with the deservedly-acclaimed Dave Stewart, coloring his own work here we see a further emphasis on separation of foreground from background: how a sense of deep focus with varying properties can call attention to such things as the contrasting colors within a comic book held in a character’s hand, the ink line rendering it bare traces of its zoomed-in self.

Creature of the Night is a story about Batman told via the character existing in comic books within the story's world, where a 'Bruce Wainwright' fixates on the superhero both before and after the death of his parents. The drawing of self-consciously-presented “Batman comics” within the pages of the series is another impressive thing, and one that creates a parallel to Mazzucchelli’s strip. While Mazzucchelli redrew iconic panels within the context of a nine-panel grid, presenting them as incidental miniatures, Leon’s approach to the comics-within-the-comic is beautiful: images enlarged not just to highlight the dots of the four-color printing process, but the brushstrokes that define the shapes. His pastiches don’t aim for a reductive approximation, but an enlargement of the elements of artistry that often go ignored when looking at a comic as a nostalgic curio of the era when it was produced. The colors themselves are bright; light in a way that, within the larger 'real world' of the story, is often used for deeper backgrounds. Meanwhile, the vivid brushstrokes become tangible when something is in the extreme foreground, moving away from a light source into unfocused shadow.

The images presented within the comic as fictive for being Batman comics are fictive within our world as well, in that they’re not recreations of extant imagery. At the beginning of issue 3, Leon fakes a circa-1972 Detective Comics cover treatment, but there’s no such issue with the cover depicted, which features a drawing that seems blown up from a smaller panel, rather than retaining the proportions a cover would have. Wainwright is later shown to own, and have defaced, a page of The Dark Knight Returns original art, but a close examination shows Leon has not actually redrawn a famous Frank Miller layout, but reconfigured a few classic images from an iconic sequence into a single 16-panel page. We also get embellished approximations of the styles of Dick Sprang and Bob Kane, and all these things are delightful. No artist is slighted, but a visual language emerges to suggest that comic books are fake when the panel is exploded.

Every Batman comic of the past 35 years is going to exist in the shadow of Miller and Mazzucchelli, of course. Creature of the Night’s conceit allows it to sidestep competition with all the varied Batman comics that exist, and instead behave as a companion piece to 2004's Superman: Secret Identity, with which it shares writer Kurt Busiek. Both Busiek's and Leon’s careers are defined in part by association with Alex Ross. Busiek made a name for the both of them by writing Marvels, a book that put Ross on the map, and Ross repaid the favor by providing cover art to Busiek’s creator-owned Astro City. Busiek's and Ross’ work played a major role, in the 1990s, in the recuperation of the superhero genre back to a more optimistic and hopeful place, away from the deconstructionist gestures of the '80s. Ross’ painted art was 'realistic' -- at least in contrast to the more expressionist styles of painted comics practitioners like Kent Williams and Bill Sienkiewicz -- in a way that served to underlie the romantic idealism of Busiek’s writing. Ross's version of realism was to make comics that say: if superheroes were real, wow, that would really be something to see. Later, when Ross’ work was at the peak of its popularity, he provided cover art and character designs for Earth X, for which John Paul Leon drew the interior art; this constitutes Leon's only extended run on a comic that’s been kept consistently in print. I recall reading there was some trepidation on Leon’s part when he got the Earth X gig; he thought his style would disappoint Alex Ross fans showing up for photorealism. The notion that superheroes are real when they are drawn in ink, with its implicit rebuke of painted superheroes as over-the-top camp, had not yet been articulated.

Mazzucchelli used preexisting images in his Year One afterword as a visual corollary to a text commentary about what struck him as the central appeal of the Batman character, after so many decades of different approaches. The conclusion he arrived at is that it’s a child’s fantasy. Busiek echoes this diagnosis: that the core of the Batman character is that, due to seeing his parents murdered, he never grew up. But while Mazzucchelli’s post-Year One career marks him as one who outgrew superheroes, Busiek’s body of work suggests he does not think this is necessary. The concept of Creature of the Night may be premised in a belief that Batman is an immature fantasy, but it’s unclear if Busiek ever really believes this thesis. So much of the story is built around the construction of parallels between the story of Bruce Wainwright and the Batman mythology, around which Wainwright has built his life, that there’s little to suggest a story needs anything more than to be about Batman. We get a Bruce, an Alfred, a cop named Gordon, a Robin. As each of these bits fall into place, the feeling is not so much satisfaction as annoyance - although this might be the point, if we view our dissatisfaction as originating from the main character’s insistence on fitting his life into this framework, rather than the insistence of an author.

Once supernatural genre elements end up factoring into the book’s ostensible real world, we get a Batman. In supplemental material, Busiek describes the work as a horror story. I don’t think this ever comes off; it might not be his genre. There’s a scene where our main character goes to a community college to learn about folklore, and where Stephen King’s The Dark Half gets an explicit shout-out; this ends up being an extremely apt point of comparison, as later on, a cloud of bats swarm like the birds in The Dark Half. Where King has his fetishes for 1950s Americana, this comic has Batman stuff. That doesn’t mean it works as horror, so much as it grasps for abstracted connections through unresolved plot threads to fill in the space left by a storytelling logic that doesn’t quite cohere. One previous Busiek attempt at the genre I can think of is an early Astro City story where there’s a Batman and Robin analog that adds Catholic imagery to the costuming, due to the revelation that the older character is a vampire. That story is comparable to Creature Of The Night in a handful of ways, but it ends with a leap in scale to include an alien invasion. It’s not really a horror story. Busiek doesn’t seem interested in fear, except to the degree that it can be subsumed into awe. His tendency towards exaltation makes a poor fit for a story about how superheroes make poor role models.

That said, craft-wise, Busiek is pretty on-point as a writer of briskly-moving scenes that enable the artist to always draw something interesting. Here and elsewhere, Busiek’s approach leans heavily on first-person narrative captions. By and large, I am not into how first-person narration works in comics: often forgetting that the voice in prose stories does interesting things, you get a sort of illustrated exposition that doesn’t leave much space for characters to reveal themselves, beyond a few adjectives for how the ever-moving-forward plot makes them feel. If the narrative voice isn’t reliably ingratiating, and the art isn’t forthcoming with its own rewards, I quickly tap out. Here, because Leon’s art is so strong, I find something pretty satisfying. Even though there’s little in the way in the way of action sequences or overt spectacle, Busiek is still scripting pages that enable Leon to show off his command of movement through space with clarity. The script covers multiple decades, beginning in the '60s and ending in the early '90, which gives an artist who is adept at drawing backgrounds plenty to do, and Leon leans into this. I particularly liked a bit in issue 3 where the placement of a 1989 Batman movie poster in an office serves as a clear marker of the space.

Leon’s work stands as a reminder of how realistic depictions of human figures in comic book art can actually be startling and vivid if given something of the excitement of life to capture, when a script does not just call for talking heads, but for human bodies moving through and interacting with their surroundings. If the digitally-modeled textures of so much 21st century comics coloring diminishes the line art to achieve a 'digitally painted' look closer to the CGI rendering found in superhero movies or videogame cutscenes, then Leon’s evident draftsmanship, which grounds his work in the observational, keeps it closer to classic cinematography - where people and locations are lit by the same sources in considered composition, rather than assembled in layers after the fact. The art remains rooted in the real, and the writing is up to snuff enough to make their collaboration achieve that oft-overlooked goal: to be a real comic book.