“No way. This can’t be right,” Mis(h)adra’s protagonist, Isaac, wonders ominously in a flashback, “This is me?” It’s a scary question to contemplate for someone experiencing an epileptic seizure for the first time. Iasmin Omar Ata’s comic Mis(h)adra is a story about the daily life and struggles of Isaac, a college student who’s just trying to get through parties, midterms, and his struggles with epilepsy. It’s a serial comic in 15 parts, with a new installment published the 15th of every month. The title Mis(h)adra, in Ata’s words (1), is a play on the Arabic words “misadra,” which means “seizure,” and “mish adra,” which is slang for “I cannot.” It’s this sort of tonal duality in the title that defines the comic’s youthful, cynical voice that also doesn’t shy away from depicting the seriousness of Isaac’s disorder.

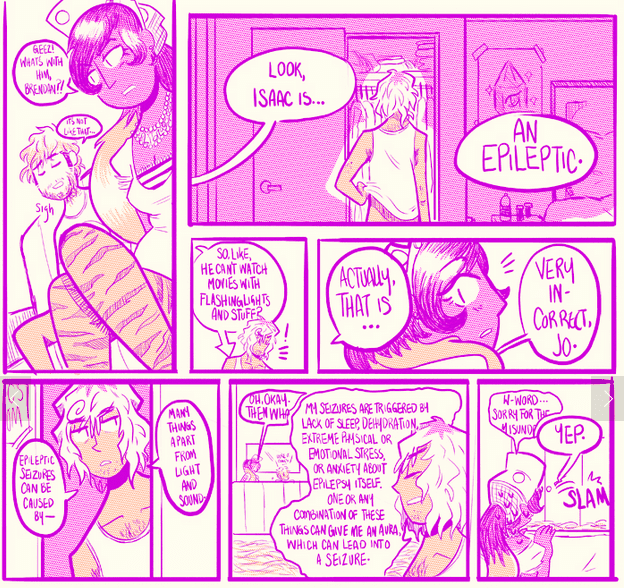

The characters that populate the story’s New York City-based, collegiate setting are often self-aware and snarky, like when Isaac’s roommate Brendan just can’t keep from cracking an “I didn’t know it was 2003 again” aside in regards to his Brand New t-shirt. Or when Brendan’s friend Jo reaches out to Isaac and breaks the fourth wall, declaring they’ve been “talking for, like, six pages.” But while Isaac’s friends are understanding, albeit often in the dark about his condition, the medical figures he encounters are difficult and misunderstanding. Doctors deny prescriptions and question Isaac’s diagnosis. As Isaac attempts to face social situations and keep up in class, it’s clear to outsiders what this condition brings to the table for many on a daily basis. What emerges from Mis(h)adra is an intimate snapshot of a life with epilepsy, one that’s grounded in an almost educational naturalism.

Mis(h)adra is a beautiful and colorful comic. Ata’s style is certainly manga-inspired, all hand-drawn, with its characters visibly animated. The eye does not get bored on these pages, as they fluctuate between boxes of all sizes and text bubbles with lines that seem to quiver during tumultuous conversation, such as the Arabic exchanges between Isaac and his father. But what’s most interesting about Mis(h)adra is the way Ata chooses to portray the physical aspect of epilepsy for readers, which steps outside the comic’s realism into something more fantastic.

The rise of anxiety and a seizure is drawn as a literal attack on the series’ protagonist, depicted as a horde of one-eyed turquoise daggers. The comic loses its more formatted, box-centric paneling, instead turning into a swirling spread of dotted lines and swords that sever, slash, and choke Isaac and his consciousness. The once bright yellow and purple color scheme of the comic is inverted, becoming a much darker set of black, red, and blue. And because these extremely different sequences, which often last several pages and appear in each issue, are presented so abruptly, they are jarring.

The rise of anxiety and a seizure is drawn as a literal attack on the series’ protagonist, depicted as a horde of one-eyed turquoise daggers. The comic loses its more formatted, box-centric paneling, instead turning into a swirling spread of dotted lines and swords that sever, slash, and choke Isaac and his consciousness. The once bright yellow and purple color scheme of the comic is inverted, becoming a much darker set of black, red, and blue. And because these extremely different sequences, which often last several pages and appear in each issue, are presented so abruptly, they are jarring.

It will be interesting to see where Ata decides to take Isaac through this series. Already beginning to open up, he seems to be coming to terms with not just the normalcy of epilepsy, but also the normalcy of people actually caring about it. “I’m always trying to stay quiet because it’s hard to talk about,” Isaac tells Jo honestly. In Mis(h)adra, it’s a conversation that certainly isn’t afraid to be louder.

(1) http://iasminomarata.tumblr.com/post/88774471328/hey-i-hope-you-dont-mind-me-asking-what-the-meaning