Ted Richards, a member of the infamous Air Pirates—the comics collective that faced a protracted legal struggle with Walt Disney Productions for placing their copyrighted characters in scandalous, non-Disney behavior—died on April 21st at Kaiser Santa Teresa hospital in San Jose, CA. The cause of death was lung cancer, according to Richards' daughter, the singer and musician Miranda Lee Richards, who spent her father's final days caring for him as his illness progressed. He was 76.

"It was really special to be with him in these last few months. It was a really special time and I'm glad I got to experience it," she said.

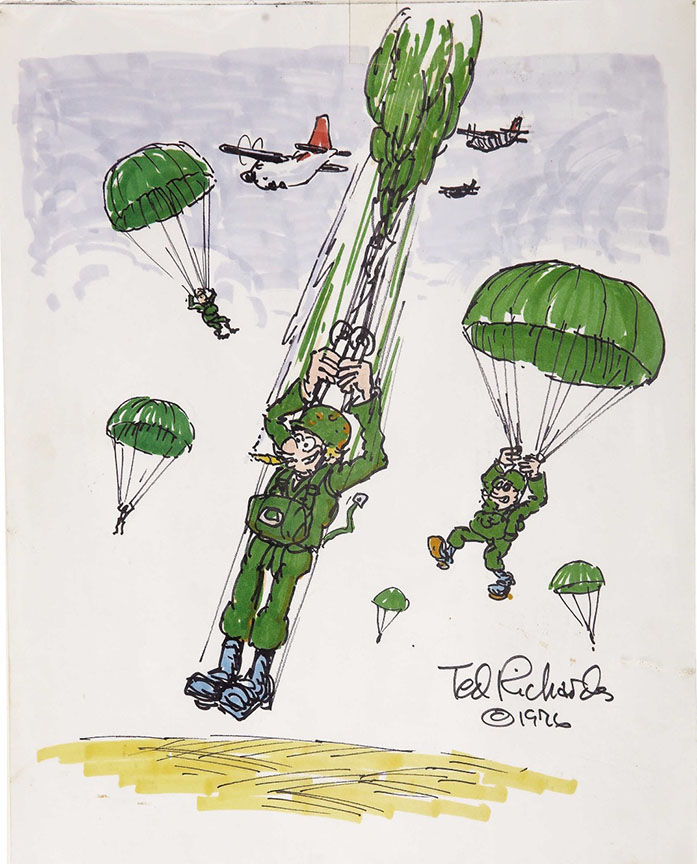

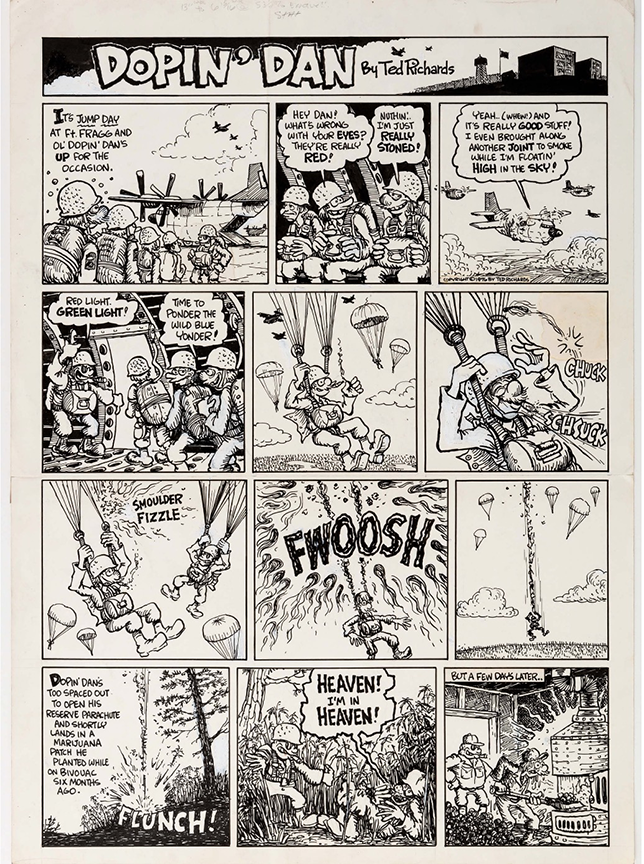

Richards, who mostly left the comics world behind in the early 1980s for a successful career in the fields of computer design and magazine editing, was best known for his Dopin' Dan character, a sort of stoner update of Beetle Bailey or Sad Sack for the Vietnam War era. Dopin' Dan's misadventures in the Army were said to be loosely based on Richards' stint in the Air Force, and unlike its often generic comic book military predecessors, Richards strove for Dopin' Dan to be a more realistic and sympathetic portrayal of the struggles faced by the American soldiers of the time.

"He served two and a half years before receiving a general discharge for (accurately) suspected but unproven marijuana use," author Bob Levin wrote of Richards in his history of the Air Pirates, The Pirates and the Mouse: Disney's War Against the Counterculture (Fantagraphics, 2003). "For most of his tour, he was stationed in Fort Benning, where he was part of the base 'literati.' They read books, watched Star Trek and ran computer programs for the entire squadron, which included the Strategic Air Command, whose nuclear armed planes, constantly heading for and being pulled back from targets in the Soviet Union, had inspired Dr. Strangelove."

"I published Dopin' Dan, and that was a huge hit. It sold hundreds of thousands of copies," Richards said in a podcast interview with ANTIC: The Atari 8-bit Podcast in 2015. "So that launched my career as an underground cartoonist. Although I never really did heavy dope stuff, or sex or what have you. It was mainly satire about the military. Political satire, and so forth. I modeled myself off a cartoonist from World War II called Bill Mauldin."

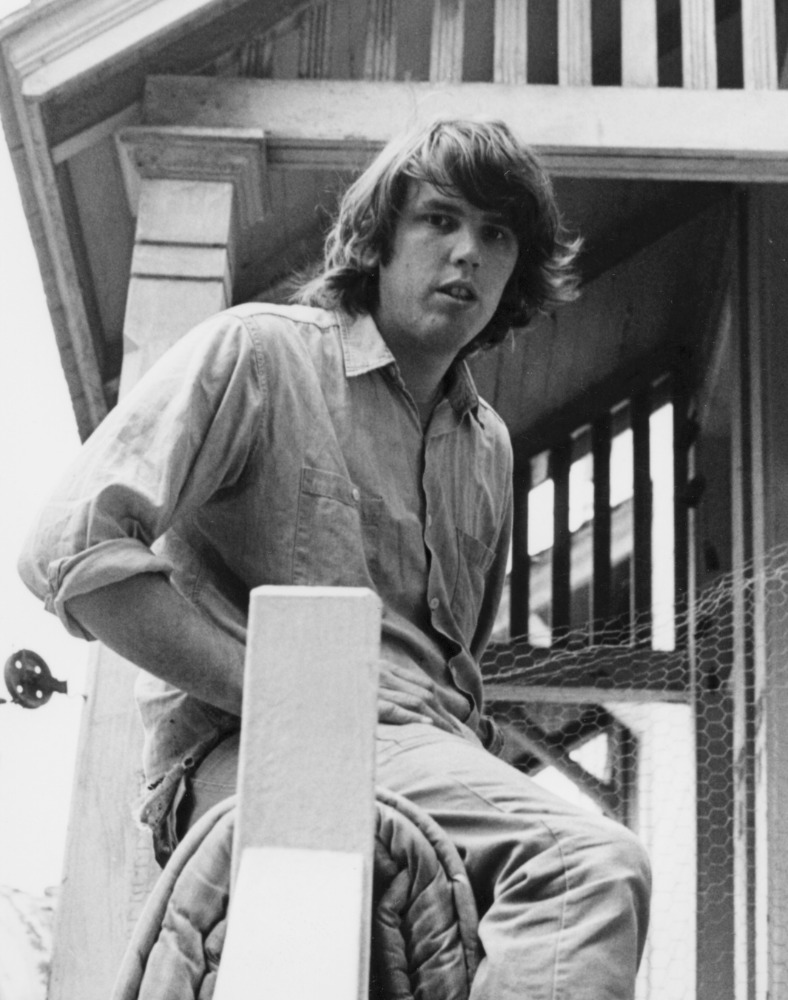

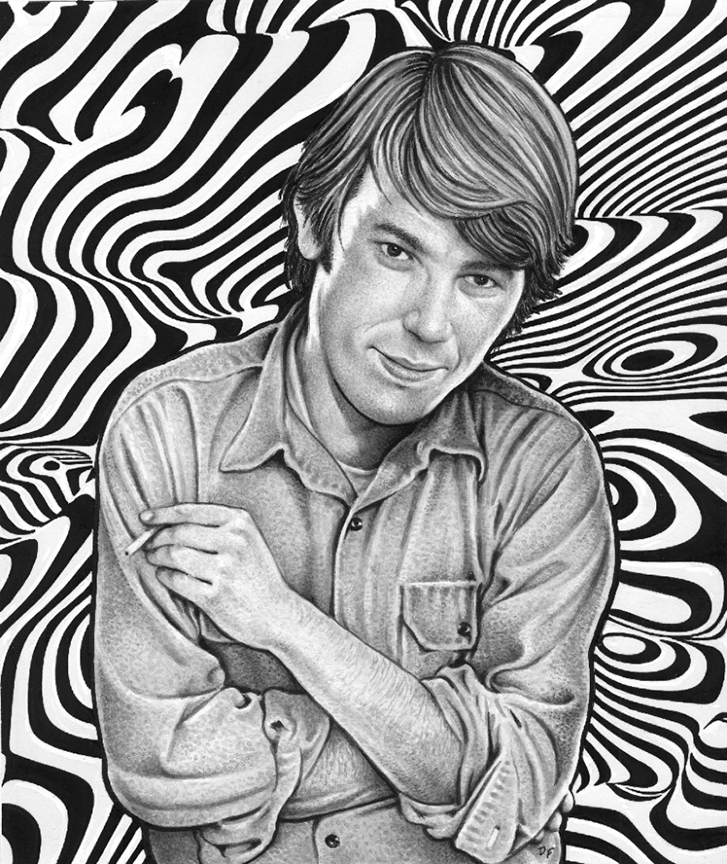

Ted Richards was born in Fort Bragg, North Carolina, in 1946. By the time he met up with the group that would form the Air Pirates in 1970, he was a "strapping, six-foot-two, 180-pound, 24-year-old," as Levin wrote in The Pirates and the Mouse. "Richards had been 'seeing' cartoons since he was five. His favorite strips were Pogo, Peanuts and Jimmy Hatlo's They'll do It Every Time. His favorite comic books were Superboy, Uncle Scrooge, and Walt Disney's Comics and Stories. He had always been 'Class Artist'; but, on the army bases of the South where he grew up, art was a seasonal activity, usually limited to turning out turkeys for Thanksgiving and Santa Claus for Christmas. The rest of the year, he played baseball, football, and worked on self-designed science projects, like building model airplanes that flew. Drawn to 'application,' not homework, he quit school in 1965 to play electric bass in a Beatles-Stones cover band. Then, with the draft closing in, he enlisted in the Air Force."

Richards grew up in a military family; his father was a Sergeant Major Green Beret in the Army, receiving a Silver Star after parachuting into Normandy with the 101st Airborne. An orphan since age 14, his father had "escaped the Pennsylvania coal mines" by joining the Army, authored a book on hand-to-hand combat for the military, and enjoyed the occasional bar brawl into his 40s, Richards told Levin. His mother was from Eufala, Alabama, and was "a portrait sketcher and tale-teller, steeped in the works of Southern writers, and could recite Uncle Remus from memory." He was devastated when he read Pat Conroy's novel, The Great Santini. "That was my story."

After leaving the Air Force, Richards briefly worked for a finance company in Cincinnati before joining the city's alternative newspaper, the Independent Eye. He soon departed with a group of disenchanted staff who formed a rival paper, the Queen City Express, where Richards served as reporter, editor, publisher, cartoonist, and "the guy who drove to the printer's," per The Pirates and the Mouse. He moved to San Francisco in 1970 with the hopes of becoming a cartoonist, but the prospects were daunting, at least in the establishment world.

"It didn't take any act of brilliance to look at contemporary newspaper strips, even in the sixties, to see that they had gotten completely sterile and rubber stamped images," Richards recalled in the March 1978 issue of Cascade Comix Monthly, a news and interview zine. "If you were a young aspiring cartoonist in the middle of the cultural revolution in this country in the sixties, you felt that... you just weren't gonna draw the crap that was coming out in the dailies. It said to you, just looking at it, 'there's no room for you'."

In San Francisco, Richards met up with Gilbert Shelton, cartoonist and co-founder of Rip Off Press, through which Richards would publish several notable comics. He also found work doing paste-up and cartoons for an alternative paper, the Berkeley Tribe, which had been founded by some ex staff members of the Berkeley Barb, one of the first and most influential underground newspapers in the country. It was at the Tribe that Richards met cartoonist and future Air Pirate Bobby London. Richards would later describe the scene as one of intense radicalism, as recounted in historian Patrick Rosenkranz's Rebel Visions: The Underground Comix Revolution 1963-1975 (Fantagraphics, 2002):

"The [East Village Other] was considered a bush paper, a bourgeoise paper by all the underground papers," Richards said. "[The Berkeley Tribe was] a younger breed. We were working on the more radical papers that had pretty tough editorial guidelines to get stuff published in it, even more so than the straight press. A lot of stuff in [the East Village Other] would never make the strainer on the papers we worked on. It would have never have gotten published."

While attending the Sky River Rock Festival in Washougal, WA, in 1970, Richards and London met up with Dan O'Neill, young creator of the syndicated strip Odd Bodkins, and Seattle native Shary Flenniken, who was producing a daily mimeographed newsletter for the festival. The four—joined by Seattle cartoonist and sign painter Gary Hallgren—soon reconnected in San Francisco to form the Air Pirates in 1971 under O'Neill's direction. The plan, as conceived by O'Neill, was to take on the wholesome image of Walt Disney with the weapon of parody.

"My purpose in using the Mouse as a character is not to destroy the Disney product, but to deal with the image in the American consciousness that the Disney image implanted," O'Neill would later state in a sworn affidavit.

* * *

When contacted by the Journal for comment, Dan O'Neill summarized the era like this:

...I'm syndicated in 1963..21 years old...Odd Bodkins...350 papers..55 million circulation ...in those days to get the job you gave your copyright to the syndicate...they own it...they can drop you and have someone else takeover if they want..their property your strip...Odd Bodkins was about the issues of my generation...the War in Viet Nam...civil rights...editorial pages quiet on these subjects...censorship ...if you mentioned something copyrighted or trademarked ,you were sued...by 1968, I've been fired three times, only to be brought back by objections from the Chronicle readers...Herb Caen ..the leading columnist in California...calls me up..his spies in the Bohemian Club listen to Richard Nixon telling Charle Theriot SF Chronicle publisher to get rid of O'Neill..Charlie says we've tried three times already...we try again in four months...don't think his audience will rise again...and I didn't either...so what to do? each time they fire me, I say give me back my copyright...no..you'll be dead someday O'Neill and we'll reprint it and get our money back... Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan both financed by Walt Disney..who sued a kindergarten over pictures of Mickey Mouse on their schoolyard wall...first step...38 Disney characters in Odd Bodkins..OWNED by the Chronicle...second part...Air Pirates perfect Disney art...in 1964, I came in contact with the Committee...improvisational theatre..Del Close founder of Second City in Chicago...I wanted to do improv in my art form..comics...in that last four months, I meet Ted...he finds Bobby..we go to Sky River, and they find Shari, and I find Gary...year later, lawsuit for a million,two hundred thousand...in that last four months, Glide Foundation publishes The Collective Unconscious of Odd Bodkins...COPYRIGHTED by the Chronicle..38 Disney characters...I walk in the Chronicle..cartoonists never know what they're doing, I tell them..I kept doing what I was doing here, and now they're suing me for a million plus..and it looks like you have about a half million in trouble in that copyright you wouldn't give back to me..and ten minutes later, my copyright is back...Doonesbury says O'Neill got his copyright back..I want my copyright back..and they all got their copyrights back...when you write about Ted, mention Dopin' Dan...gave the Army fits...the VietNam Vets against the war...all his fans..and the FBI...

In Rebel Visions, Patrick Rosenkranz offered his own account. "Early in 1971," he wrote, "Bobby London was dispatched to Seattle to round up Ted Richards, Gary Hallgren, and Shary Flenniken so they could get to work on Dan O'Neill's scheme to start a comic book company.... London, Hallgren, and Richards went to California first. Flenniken followed a few weeks later. They moved into a small studio space in San Francisco and began their collaborative experiment... O'Neill told them that he was about to begin publishing a monthly periodical. He had plans for printing deals, distribution deals, and getting his brand of comics on the supermarket racks.... Each of them took on the style of an old time cartoonist, and copied their classic comic strips."

After a period of experimentation, each chose a particular approach. London had already been stylizing his Dirty Duck work after George Herriman's Krazy Kat; Hallgren focused on Cliff Sterrett's Polly and Her Pals; Flenniken chose H.T. Webster for her Trots and Bonnie stories; and Richards was assigned Mutt and Jeff creator Bud Fisher as his model. "They decided I had a story-telling ability similar to Bud Fisher, so they assigned me Bud Fisher," Richards told Rosenkranz. "I was pretty cynical about this, to tell the truth. I did learn something from imitating the styles. I was an apprentice, in a sense, a learning cartoonist, and it was an opportunity to work with Gary, Bobby, and Dan, who had far more experience. I'd only been drawing seriously for two years when I ran into these guys. I felt quite lucky that they saw enough in my abilities to let me go with them. I was really from the back woods."

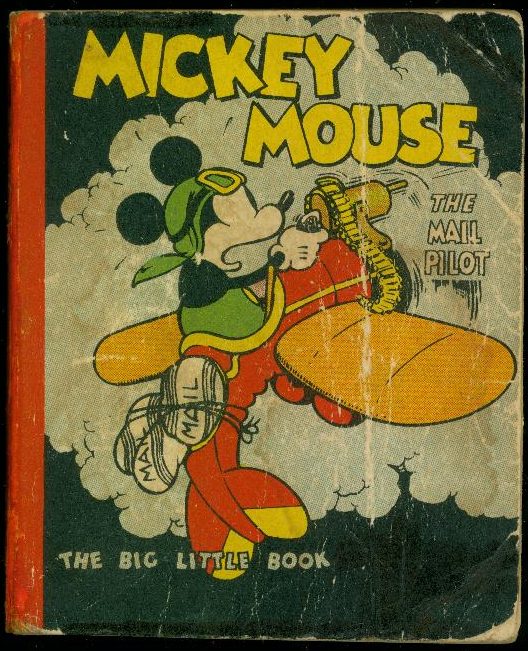

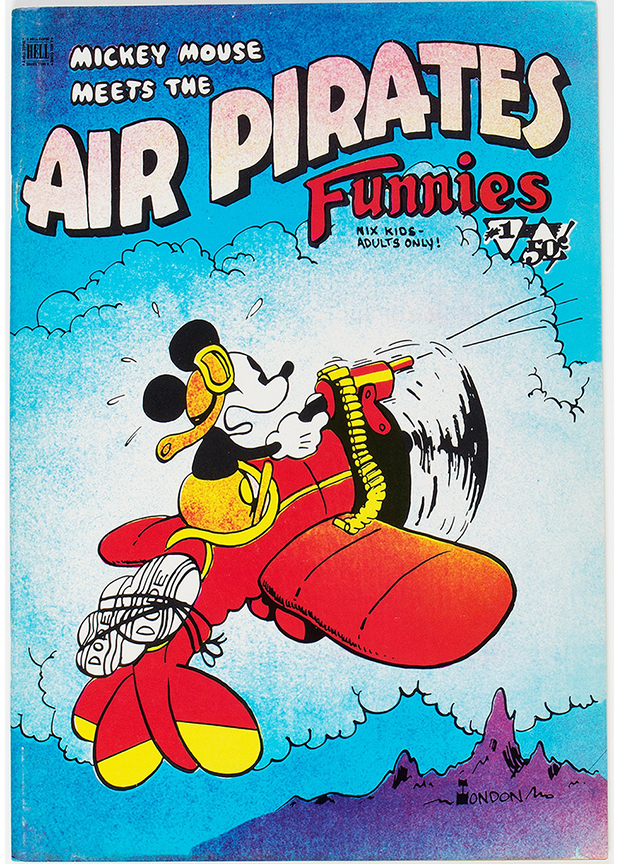

Someone in the group had the idea to base the "Air Pirates" name on elements from "The Mail Pilot", a 1933 Mickey Mouse newspaper strip storyline from artist Floyd Gottfredson in which Mickey battles Peg-Leg Pete and others to break up a crime ring located high up in the sky in a "Pirate" blimp. It was one of the most popular Disney stories of the era, available to readers for years via Whitman Publishing's 1933 Big Little Book edition. While the actual "Air Pirates" name never appears in that story—or in any other Mickey Mouse story, according to several Disney historians contacted by the Journal—on page 208 of the Big Little Book, the term "pirates of the air" appears, which is where the name likely originated.

"Certainly 'pirates of the air' would have made a less snappy name for the group," Levin wrote in an email to the Journal. "'Airplane of the Jefferson' wouldn't work either."

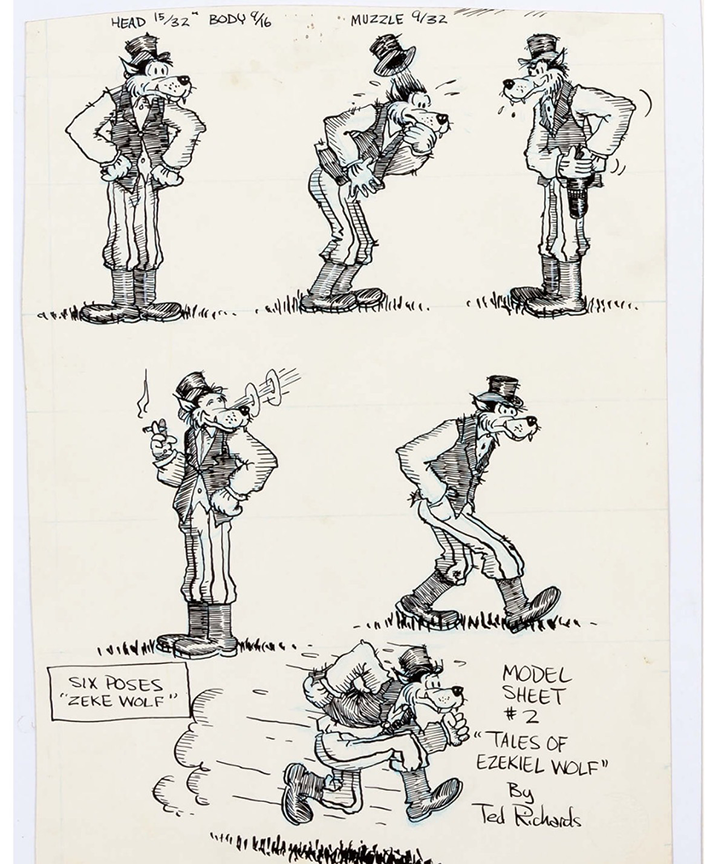

Air Pirates Funnies #1, released in July 1971 by "Hell Comics" (actually the underground publisher Last Gasp), features a recreation by London of the Big Little Book cover, but with bags of "dope" (instead of "mail") strapped to the tail of Mickey's plane. London led off the issue with several Herriman-influenced Dirty Duck stories, while Hallgren had a peeping tom story, "Keyhole Komix", featuring Donald Duck as a "Nameless Pervert" watching Minnie Mouse take a bath. For his part, Richards added three Dopin' Dan strips that ran his Zeke Wolf—a parody of Disney's Big Bad Wolf—along the bottom of the page. And O'Neill's two "Silly Sympathies" features placed familiar Disney characters like Mickey, Minnie, Goofy, the Phantom Blot, etc. into a setting full of sex, drugs and dirty language. Looking back, more than 50 years later, it's all pretty tame stuff. But at the time (and still today), Disney was known as a litigious company, and the counterculture was already under attack on many fronts.

"Basically it was O'Neill's idea to take on the Mouse," Hallgren told Rosenkranz in Rebel Visions. "To actually get up and take a big swipe at the Disney organization. He wanted some help. We all fell together on that particular point and that's how the Air Pirates comics were produced."

A second issue appeared a month later, notably continuing O'Neill's Mickey/Minnie Mouse storyline and expanding on Richards' Zeke Wolf/Three Little Pigs riff. And then someone connected to Disney got copies of the comics into a boardroom meeting.

The Mouse was not amused. If O'Neill's wish was to enflame Disney's wrath, he got what he wanted.

In October 1971, Disney initiated legal action against O'Neill, Hallgren, London and Richards. Flenniken was spared, as her work did not appear in either of the Air Pirates comic books; she also never copied any Disney characters. "Going to prison for drawing Mickey Mouse was not attractive to me," Flenniken told the Journal. "That was [Dan] O'Neill's dream. In truth though, I was not a good enough artist [at the time] to be included."

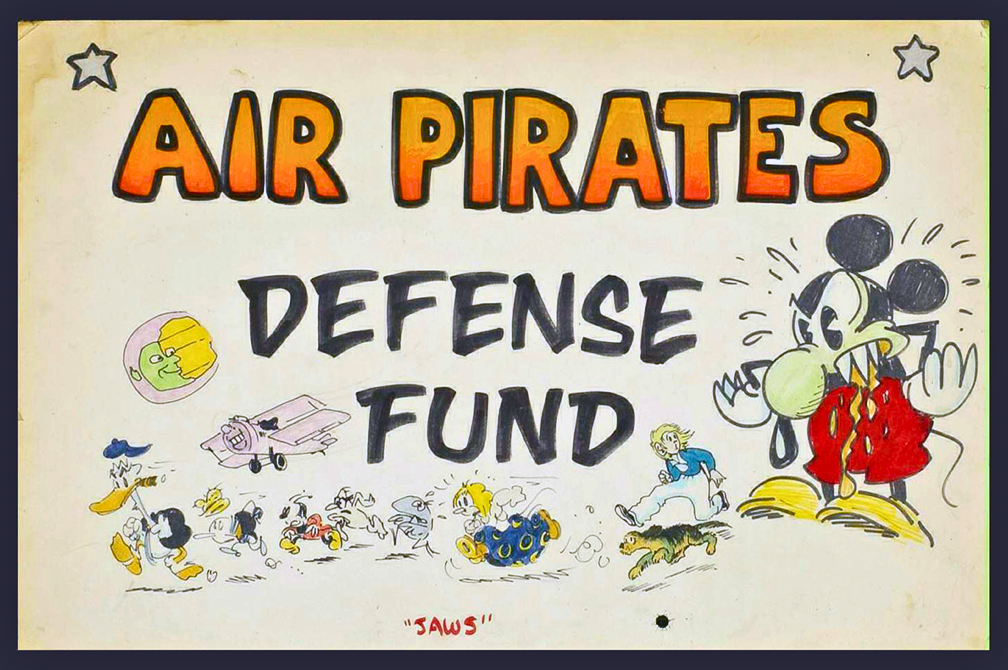

The civil lawsuit raised several causes of action, including copyright infringement, trademark infringement and unfair competition. Disney later joined Last Gasp's publisher, Ron Turner, in the lawsuit. The Pirates responded by asserting that their parody constituted fair use, as well as protected criticism under the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. Disney sought damages of more than half a million dollars.

The courts were not amused either. As the Honorable Walter J. Cummings wrote for the United States Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit: "The names given to [the Air Pirates'] characters are the same names used in [Disney's] copyrighted work. However, the themes of defendants' publications differ markedly from those of Disney. While Disney sought only to foster 'an image of innocent delightfulness,' defendants supposedly sought to convey an allegorical message of significance. Put politely by one commentator, the 'Air Pirates' was 'an 'underground' comic book which had placed several well-known Disney cartoon characters in incongruous settings where they engaged in activities clearly antithetical to the accepted Mickey Mouse world of scrubbed faces, bright smiles and happy endings'."

The legal battle was waged for years, with the courts showing little sympathy for the Air Pirates' defenses. Ultimately, in 1979, after numerous rulings and appeals, the Supreme Court of the United States refused to hear the case; citing to the controversy in a later, unrelated fair use opinion, Justice Anthony Kennedy referred to the Air Pirates as "profiteers who [did] no more than... place the characters from a familiar work in novel or eccentric poses." A settlement was reached with Disney, which agreed not to enforce any monetary judgment. Some of the group members viewed the outcome as a victory; O'Neill, who had continued drawing Mickey Mouse parodies despite a court injunction, avoided jail time for contempt of court.

Walt Disney Productions v. Air Pirates continues to serve as a case study for law school students in the country, covering topics such as copyright and free speech, among others.

But the Air Pirates remained prolific artists, rather than simple footnotes in legal history. O'Neill continued to draw comics, became involved in Irish politics, and briefly operated a pirate radio station. London's Dirty Duck ran for many years in National Lampoon and Playboy; from 1986-92, he wrote and drew King Features' syndicated Popeye newspaper strip. Hallgren moved toward commercial art, with work published in National Lampoon, MAD magazine, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal and other publications; since 2015, he has performed ghost artist work on the syndicated Hägar the Horrible newspaper strip. In the 1970s and '80s, Flenniken's Trots and Bonnie strip ran in National Lampoon, where she also served as an editor. In 2022, New York Review Comics published a gorgeous collected edition.

* * *

Ted Richards steadily produced great work during and after the Air Pirates saga. In addition to the Dopin' Dan comic book series, published by Last Gasp, he wrote and drew syndicated strips—E.Z. Wolf's Astral Outhouse and The Forty Year Old Hippie—that ran in college papers and alternative weeklies throughout the country via Rip Off Syndicate, a division of Rip Off Press. Richards also created what may have been the first ever skateboarding-themed comic strip with his Mellow Cat series, which began running in SkateBoarder magazine in 1978. His work regularly appeared in the Rip Off Comix and Quack! anthologies, he appeared in all five issues of Kitchen Sink's notorious collaboration with Marvel Comics, Comix Book, and was a key contributor to Give Me Liberty!, Rip Off Press's bicentennial look at the American Revolution.

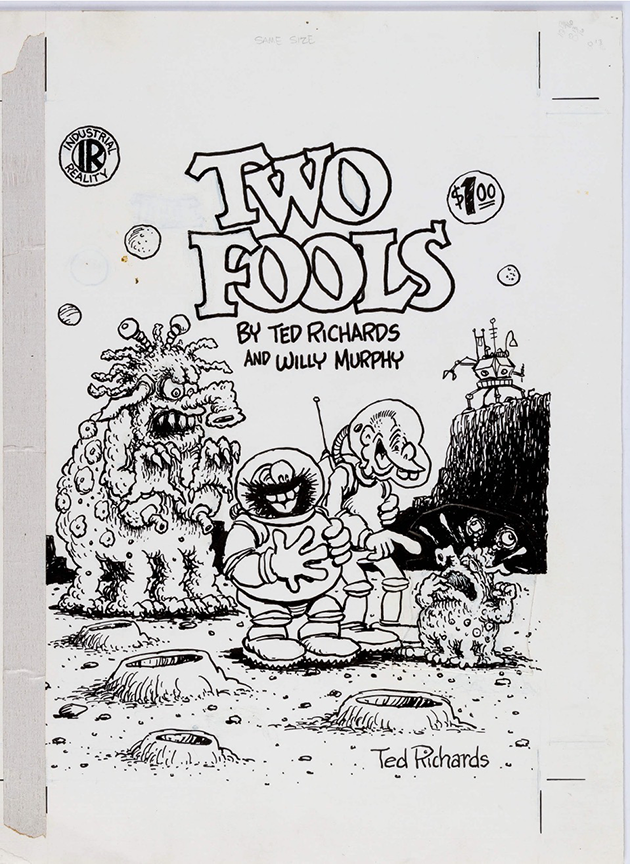

Perhaps lesser-known, but a personal favorite of some, was Richards' collaboration with Willy Murphy and Justin Green, Two Fools, which ran in several anthologies and was collected into its own comic book in 1976.

By the early 1980s, Richards began transitioning away from comics and into the technology industry in Silicon Valley. He had developed a friendship with British millionaire publisher/poet Felix Dennis, who, among many other things, had gotten his start with the Australian/UK counterculture magazine OZ (which had many legal issues of its own). Dennis was a UG comics fan and had been running a strip by Richards, "Clive's Computer", in one of his magazines. Richards was manning a booth for Dennis at an Apple computer event in San Francisco when he met a representative for Atari, Inc., which had recently launched its own home computer line. In 1981, Richards was named editor of The Atari Connection magazine, Atari's in-house computer publication, where he eventually became publisher and editor-in-chief; he also provided marketing and communications management at Atari until he was laid off in a 1984 culling of staff.

"I was very interested in computers," he told the ANTIC podcast. "I always had a scientific side to me, and [a] technical side, and I followed all of the developments of personal computers. When I was in the Air Force, prior to all this, I worked in computers. I worked in personnel, and I did computerized records for people and so forth."

In a memorial notice, Richards' family summarized his later work in tech, which occupied much of the second half of his life: "In 1987, he founded AdWare, providing software products and design services for computer clients, including Apple and Microsoft. Among his innovations was the first 'shopping cart' for an e-commerce site. From the 1990s, he became a web site developer, offering enterprise-level development services, consulting, web design and information architecture. In the 2010s he was a principal designer for Deep North, Inc."

On Christmas Eve, 2022, Richards created a GoFundMe page revealing that he had been diagnosed with small cell lung cancer and had been undergoing immunotherapy treatment for the past year. In March 2023, his health began to "rapidly deteriorate after immunotherapy was deemed ineffective for his lung cancer treatment," Miranda Lee Richards wrote in a posthumous update. "In April, upon further evaluation by his oncologist, it was determined that he was too weak to accept the next phase of chemotherapy. This, in effect, began his end stage of life -- within ten days of being admitted to the Kaiser San Jose Santa Teresa facility, Ted was no longer with us, passing peacefully during his afternoon nap on Friday, April 21st, 2023."

"I'm sorry to see him go," said Bobby London, who donated the proceeds from an auction of an early Dopin' Dan strip to Richards' campaign. "My condolences to his family."

Richards is survived by his wife, Markene Kruse Smith, their son, Samuel Ryan Richards, his daughter, Miranda Lee Richards, brothers Ben Richards and Matt Richards, sister Shirley Richards, and former wife, the cartoonist Terre Richards.

* * *

In the space below, friends and family share some memories about Ted Richards.

Gary Hallgren

(cartoonist/Air Pirate)

Let me tell you how I met Ted. He walked into my shop, Splendid Sign Co. in Seattle, late fall 1970, with a portfolio under his arm. He was tall and shaggy and scruffy, the veritable embodiment of an itinerant underground cartoonist.

He said he had just arrived from California where he had met and stayed with Dan O'Neill and Bobby London. I knew Dan from the Sky River Rock Festival but had not met Bobby. I thought Ted's cartoons and personality were very strong, so when I heard from Dan that his proposed comic book studio would include all the aforementioned, I was enthusiastic. That winter Bobby arrived in Seattle as well. When we all met at a crash house on Capitol Hill, Bobby mentioned a local cartoonist woman he was hot for.

Of course that was Shary Flenniken.

O'Neill called for us all to come to San Francisco in May and we would get to work bringing Disney to its knees. Ted and I hitched a ride south in a freshly refurbished bread truck with people from Capitol Hill… Ted was driving on the coast of Oregon when he mentioned he was a little too stoned and who wanted to take over? I was a little too stoned too, but that's never been an obstacle. It's weird but I can't remember if Bobby was in the bread truck too. I know Ted was and we became mates on that ride.

What happened after we arrived in San Francisco is another story.

Gilbert Shelton

(cartoonist, publisher via Rip Off Press)

Ted Richards was an outstanding underground cartoonist. We worked together on several projects for Rip Off Press, including Give Me Liberty! A Revised History of the American Revolution and Fat Freddy's Comics & Stories #1. Ted had a good sense of humor, which can be seen in books like Dopin' Dan and The Forty Year Old Hippie. We also played together on softball teams, where he starred. It was too bad he left the underground comix business and went into advertising, but the money is better.

Bob Levin

(author, The Pirates and the Mouse)

I met Ted when I was interviewing people for The Pirates and the Mouse, and we kept in touch, even if it was no more than an Xmas card. I knew he'd had cancer, and, even though I hadn't heard from him in a couple months, I was hoping... Now he's the third fellow with whom I'd had lunch to pass within a couple of months.

Two things about Ted stand out in my memory. First, counter to the traditional UG/Alt cartoonist profile of being put upon by high school Hot Shots, Ted WAS a high school Hot Shot. (Played football and baseball and joined a Stones/Beatles cover band.) Second, following the crash-and-burn end of the UGs in the '70s, instead of taking the more common path into a descent into alcohol and/or drugs, Ted established an even more successful career as a corporate creative director in Silicon Valley.

He never lost his commitment to the counterculture spirit though. He was loyal to his compatriots, and its ethos lived within him and the work he left behind.

He was a good guy.

Patrick Rosenkranz

(UG comics historian)

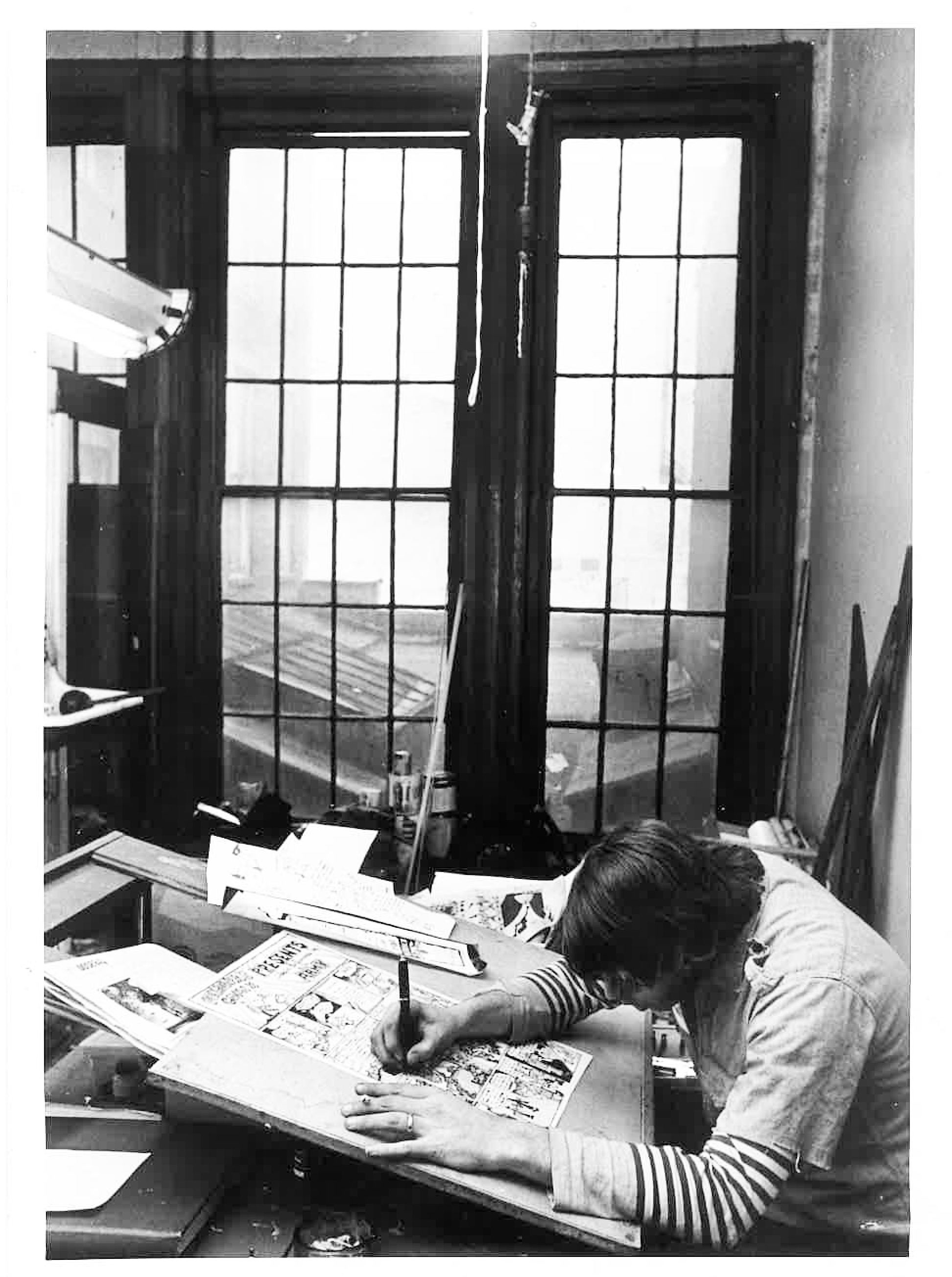

I last saw Ted Richards in 1976 at Rip Off Press. I stopped by to visit while he and Gilbert Shelton and Willy Murphy were working on Give Me Liberty!, a comic about the American Revolution. Completed pages and sketches were pinned to the walls around the room and large paper drawings of the principal characters stood watch. Gilbert and Ted worked near the windows looking out to the bar across the street, while Willy worked on a ping-pong table near the middle of the room. After a while they took a break and challenged me to a game. All three thoroughly beat my ass.

I could see they spent a lot of time on that table.

Rick Marschall

(comics historian)

My "mind" goes back 45 years, since I almost worked with Ted Richards - or tried to get him work in newspaper syndication. I liked Ted enormously and loved his work just as much - unaffected, fun, passionate about cartooning. To me he embodied, or kept alive, cartooning's traditional sheer "fun". A loose drawing style, a lot of detail-work (enjoying every line on paper), crazy characters and storylines.

I had been comics editor at three newspaper syndicates and, by the dates on papers in my files, I was already an editor at Marvel Comics, but still determined to get newspapers to pick up new, fresh comics. Ted was doing E.Z. Wolf in a daily strip format for alternative papers, and I thought it an easy presentation to pitch to syndicates.

As we know, no syndicates "bit". I showed material by Bobby London and Gary Hallgren at the time too. But Mary Worth, Brenda Starr and their friends would not nudge over…

Ted and I put a lot of work into the presentation kit. Here is some material he put in my hands: his hopes; his views of the medium and the industry; his bio, including his schooling in subjects such as History of Christian Thought I and II, and Creative (of course!) Writing; and the military background of him and his father. Him in the U.S. Air Force, his father in the Green Berets.

The 30-year old Ted, doing The Forty Year Old Hippie and so much other great work. Ahead of his time? All-time great? Fast Draw indeed.

Larry Gonick

(cartoonist)

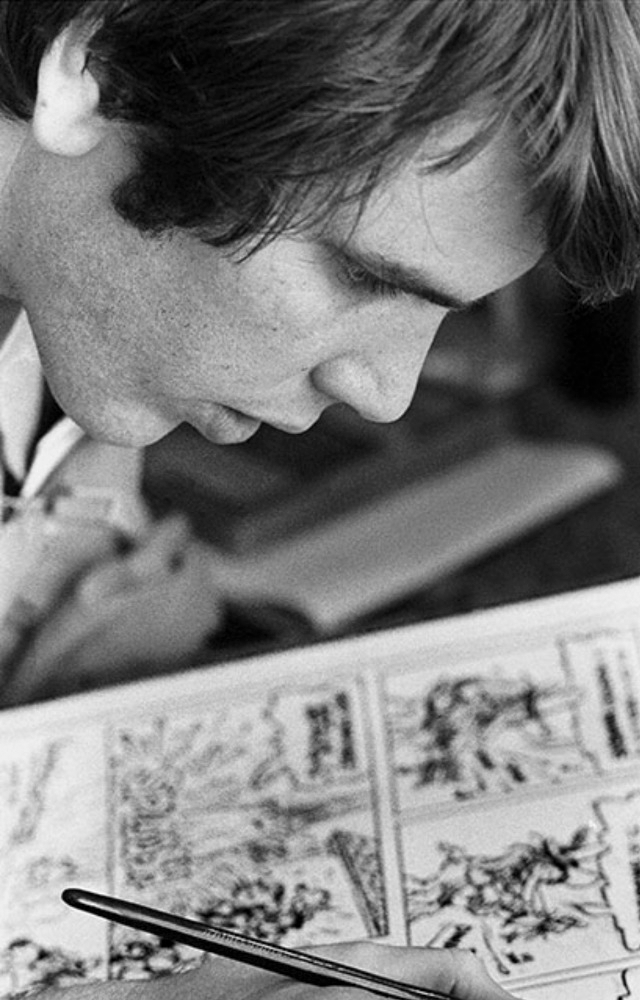

When I moved to San Francisco in 1977, I landed at Rip Off Press because Gilbert Shelton liked my early history cartoons. There I was surprised to find Ted Richards hunched over a drawing board, cigarette in hand, contributing to the Rip Off Syndicate, doing comics for them to publish and playing competitive ping-pong when they took the box of grade-B weed off the table.

Ted said he was ready to get out of there and proposed getting studio space together. I LOVED Dopin' Dan, and said hell yes. With J. Michael Leonard we formed Fast Draw Studios, which lasted a couple of years.

Ted was fascinating and complex. He was a highly conscious artist, who rolled theories of the hero's quest and other folkloric ideas into his seemingly spontaneous down-home (a twisted home, to be sure) productions. I always admired his way with a gag, which tended to be roundabout and droll, without the stereotyped Bada-boom that some of the rest of us can’t seem to avoid.

He was also a product of his military upbringing. He wasn't always as genial as his sense of humor on the page. I’ve heard him referred to as a "hitter" [both aggressive in umbrage and involved, on occasion, in fist fights], and there were times when he clearly showed that he felt like the alpha in the place. He could also be generous. When he launched Mellow Cat, he overpaid me to do the lettering so I was sure to make rent. Of course this was also calculated on his part, as it kept the studio going. Like Zeke Wolf, Ted was a calculator. And he had to be: he had no resources but his own wit and drive to fall back on.

Besides the Mellow Cat, he was also doing some Ezekiel Wolf strips and the great Forty Year Old Hippie. Forty looked old at the time. And remember, one of the Hippie's foils in the commune was the vaguely-gendered, personally autonomous Child Person. How prophetic was THAT?

He was also a chain smoker, and it killed him. Took a long time, though.

After the studio broke up, Ted reinvented himself in the computer world as a user interface designer, and we mostly lost touch, except for an occasional phone call. The most recent one was in January after his annual Christmas e-card. Last year's was clearly shaky - shakier than usual, I mean, but I believed him when he said his tumors were shrinking and he was probably good for a year before they changed the chemo. I should have realized that he was calling to say good-bye, though.

He was lucky to live at a time when his highly original ideas could find expression. He had a big presence, and he leaves a big absence.

Steve Ditlea

(writer, friend)

Ted Richards may not be as well known as his underground comix contemporaries Gilbert Shelton and R. Crumb, but in retrospect he was the most deft in capturing the rebellious spirit of the 1960s through the 1980s in the USA. Richards was a consummate chronicler of emerging sub-cultures, like the weed-smoking military of the Vietnam War era with Dopin' Dan and the kozmic skateboarding scene with Mellow Cat, but The Forty Year Old Hippie tracked the widest swath of alternate consciousness from fringe to mainstream.

In 1976 The Forty Year Old Hippie appeared in college newspapers and alternative weeklies, at a time when the idea of a long-hair in strange garb exploring out-of-it lifestyles beyond one’s 20s was part of the joke. Based in San Francisco, one of the poles of hip culture, Ted was often just reporting on his own existence. A good example was the Hippie's gender-neutral offspring "Child Person", occasionally identified as "he", but actually Ted's daughter Miranda, who grew up to be a talented singer-songwriter. By 1984, when this New York editor commissioned the last appearance of The Forty Year Old Hippie for an anthology on computer culture, Ted had made the transition to a straight job in Silicon Valley and the hippie sensibility had become ingrained in the Tech Revolution.

Fortunately, those who weren't there (and those who were but don't remember) can relive the Forty Year Old Hippie's progress for free, thanks to two online archives. The Internet Archive offers two complete 1976 and 1979 comic books published by Rip-Off Press. At Atari.org, you can find the last two episodes.

After his death, members of Ted's family wondered if wherever he was he might be sketching the long-delayed sequel, "The Seventy-Six Year Old Hippie's Final Trip". The Hippie’s tag line was "Ain't Been This High Since The Pot Of 69". You could still be there…

Robert Beerbohm

(comics retailer, historian)

Learning recently that Ted Richards passed away struck me in a way I find a bit difficult to articulate. But I will give it a try, as some of us wrestle with memories from over half a century ago; he was my friend, back in the day.

I first began to see late '60s 'alternative' creator-owned comix via [early comics retailer] Bud Plant at a 1969 Dallas comics show. Then in 1970, at Dirt Cheap, an alternative culture bookstore near the University of Nebraska at Lincoln, when I was a student there.

Through the summer of 1972, Bud Plant and I had been forming the nucleus of a comic book dealer caravan (of sorts) which saw other young guys like us come in and out of a schedule which saw, for the first time, a circuit route begun in Oklahoma City, mid-June. Then, going in a semi-circle arc north and east with fabled Seuliungcon [i.e., the New York Comic Art Convention organized by Phil Seuling] as a mid-point anchor. There was Chicago, Baltimore, and other stops.

Shortly after Seulingcon, July 4th weekend, a Federal judge ruled against the "Air Pirates", which began buzzing inside comics fandom. With our newly-fashioned circuit ending at the mid-August first El Cortez Hotel show [one of the early editions of what is now the San Diego Comic-Con], we heard this more and more. Air Pirates #1 and #2 began to be hotly dealt "under the table" with rumors abounding Disney had secret agent "goon" squads on the prowl.

Late August, Bud & I moved into 458 Harmony Lane in San Jose. He had talked, cajoled me a bit, into driving north to San Jose from San Diego... we ended up starting a comic book store at the end of August. With John Barrett, we co-opened the first Comics & Comix location at 2512 Telegraph Ave. near UC-Berkeley...

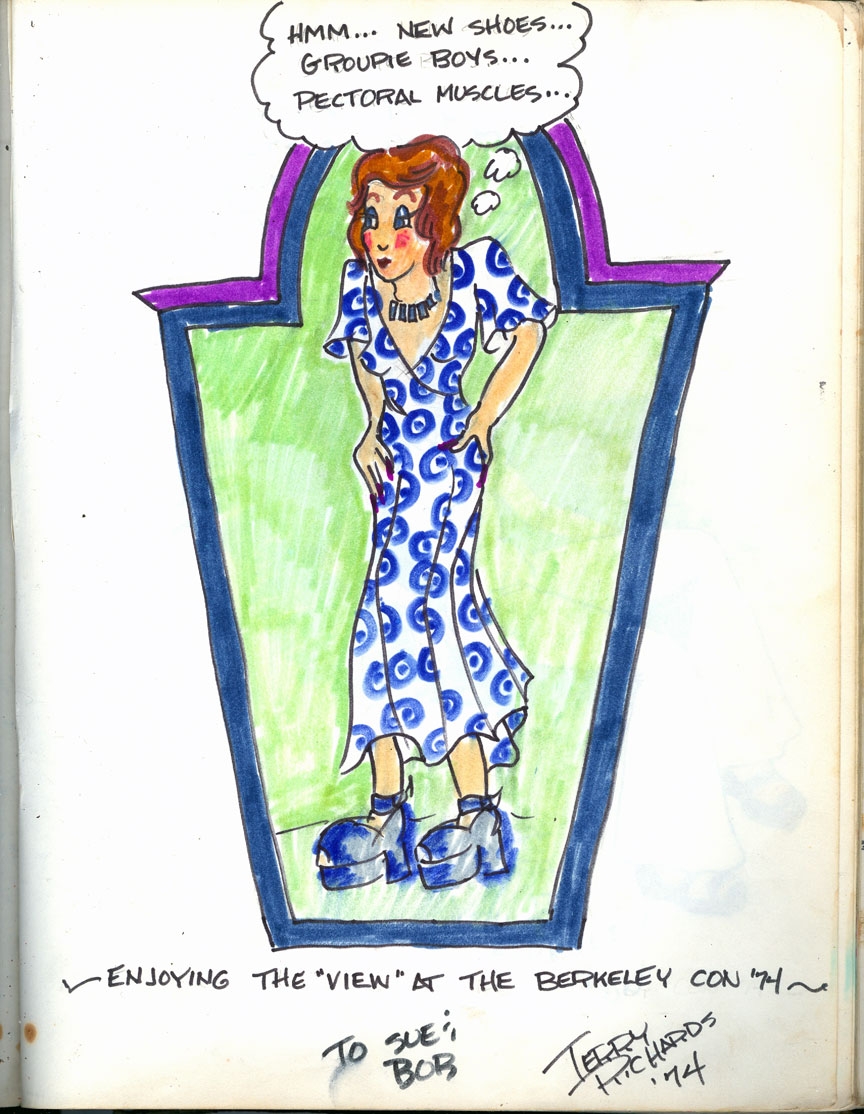

Over the next year, virtually all the Bay Area comix creators began wandering and filtering through our growing gig there.... We co-hosted the first Bay Area comic book convention [the Berkley Comic Convention] in April 1973 on the 2nd floor of ASUC [a student union] on the UC-Berkeley campus, centered on creator-owned, royalty-paying comic books. We got most all the Bay Area comics creators to come but Crumb.

This is when I truly began to meet the Air Pirates themselves in person. Outside of the comic book store, where daily life on the Ave. was sometimes pitched warfare, which is yet another tale for another day. Knew them all. In March '73, Print Mint had brought out Zap Comics #6 with a then-unprecedented 100,000-copy print run. In April we hosted Berkeleycon. Rip Off Press and the other Bay Area publishers were pumping out hit after hit for us.

Last Gasp was publishing Ted's Dopin' Dan, beginning shortly before we opened up that first C&C. Issue #2 published Feb. 1973. These guys would come thru periodically, semi-randomly, checking out how their comix were doing. Reader reactions. What we thought might need expanding upon in other comix work being planned. Plus, they were all coming thru checking out all the cool vintage comics & related popular culture we had coming in.

Then in June 1973 SCOTUS handed down their Zap #4 Crumb "Joe Blow" story ruling [denying certiorari] which was part of this insidious plot establishing the concept of "local community standards shall prevail" without defining what 'local' 'community' or 'standards' were [see Miller v. California from the same year]. Upwards of 80 more comix busts happened thru 1973. Phil Seuling was one of them.

The Bay Area went publishing dark for a while. Most all projects placed on hiatus. Crossing state lines with certain comics was now a real Federal crime. 1974 was a bleak year in many aspects of the non-Code comics business, as the national busts over comix scared many into inertia.

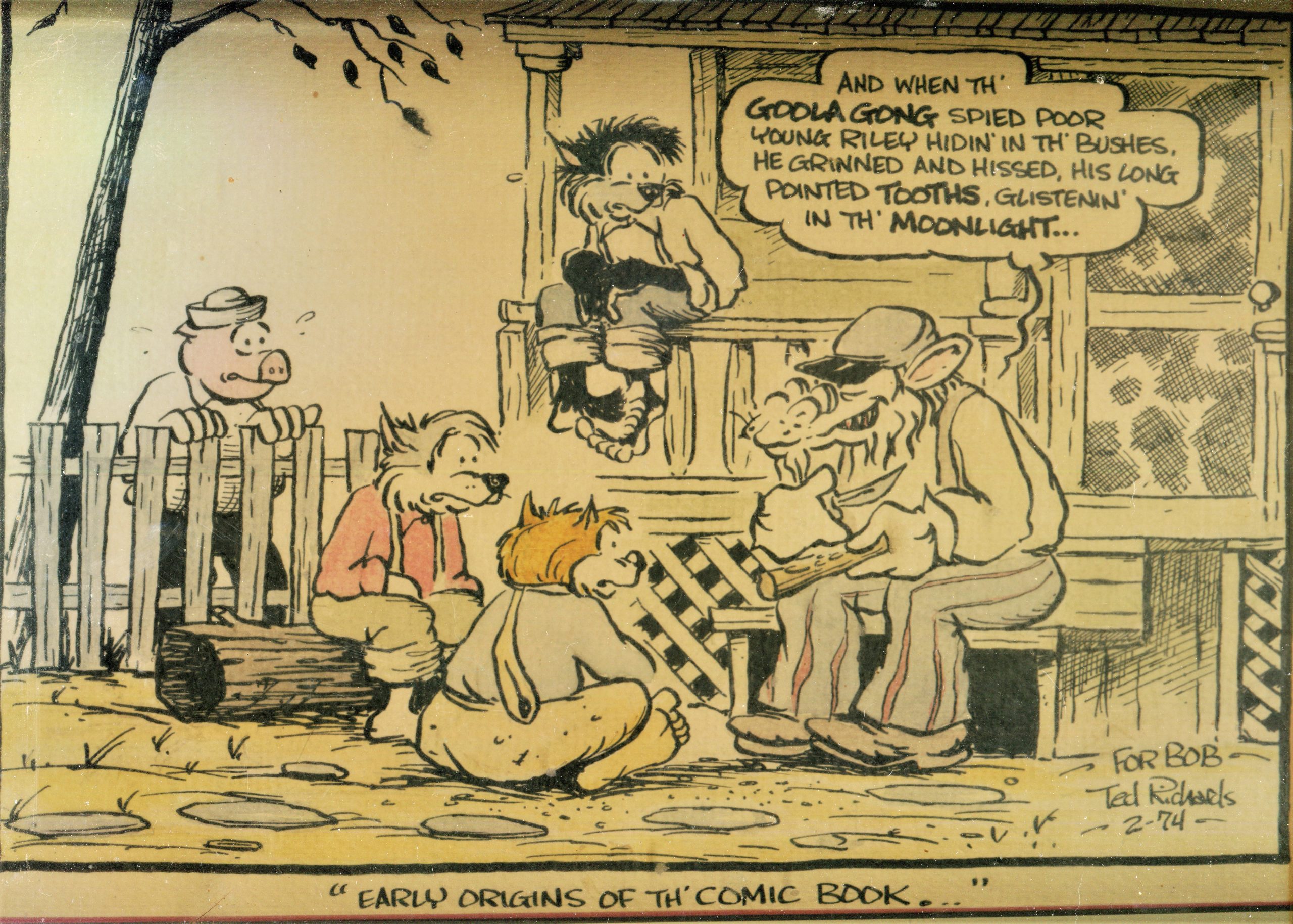

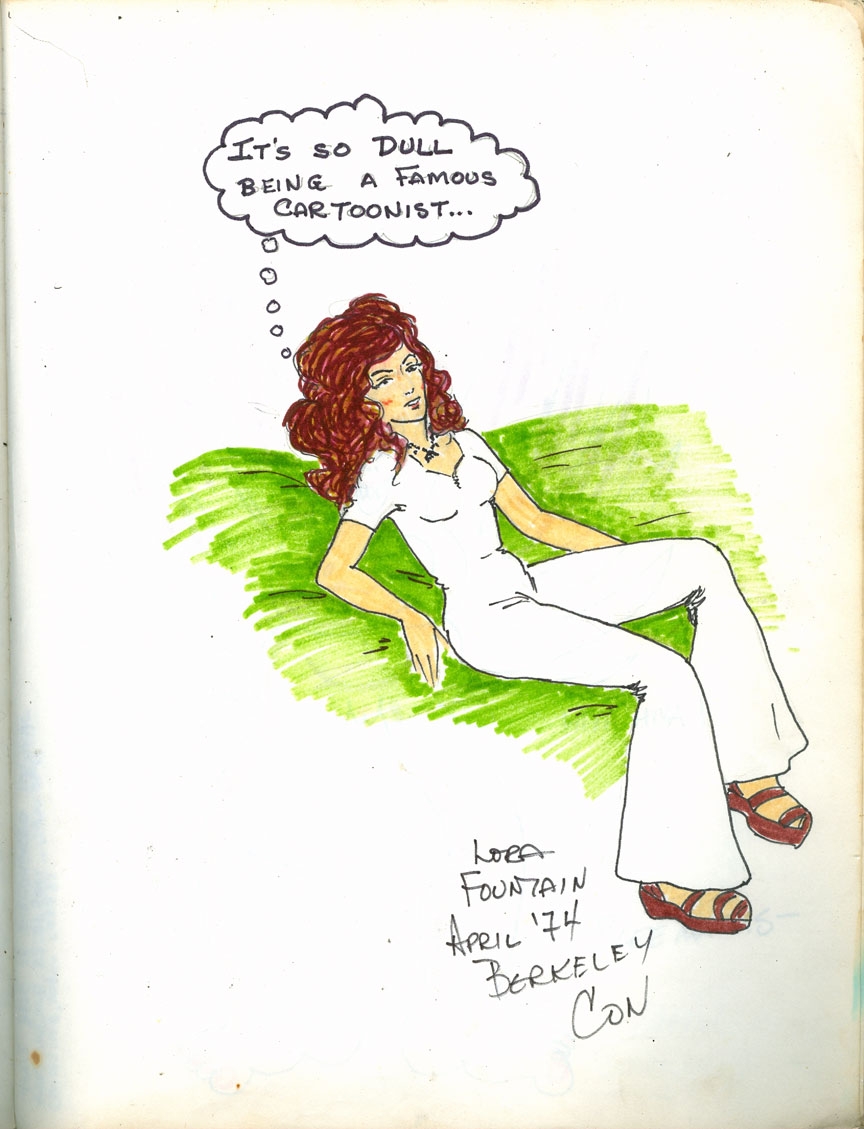

There was also a second Berkeleycon wherein Ted drew in my comics memory book his Ezekiel Wolf character blankly fishing, pondering the state of the Bay Area comix business which was then on semi-hiatus/almost-implosion mode. His then-wife Terre Richards was also working on becoming a cartoonist. She was set up with Gilbert Shelton's wife, Lora Fountain. They both succinctly summed up their feelings regarding comic book shows.

A couple months before: Ezekiel Wolf explaining early origins of comics from back in the day. It's a watercolor painting Ted did for me as part of a trade, with me ending up with the original art. Ted got some '30s Disney treasures. I include here a Big Bad Wolf 1934 book as a sample. Fun days.

Thru all this going on, Dan, Ted & Bobby chose initially not to settle. Thought they could fight The Mouse. This led to a disintegration of the Air Pirates as a viable gig...

Ted tried out Dopin' Dan... [at] Keith Green's bold Cartoonists' Co-op Press, which saw creators basically self-publishing. In 1975 into 1976, Ted did two issues [reprints of the first and second Last Gasp issues] thru Green's then-innovative plan of getting pre-orders in advance of press time. If pre-pay, the discount got even better. Product in, turn it all over, then get out; repeat if the first one sold well enough.

Phil Seuling expanded upon Keith Green's initial plan of pre-ordering, pre-selling wholesale larger lots to include NYC-based Comics Code titles as well.

In 1976, Ted was part of Gilbert Shelton's crew creating one of my favorite comic books, Give Me Liberty!, along with Gary Hallgren and Willy Murphy. They present many facets of then-little-known American history, centered around the Revolutionary War. This is a fine comic book I can still re-read to this day. The enjoyment has never waned.

Ted would come thru my stores, as he would other Bay Area comics stores. [The Air Pirates] also embarked on a Mouse Liberation Front campaign, traveling the country setting up to conduct benefit art sales & auctions. Many rallied to their ill-fated cause. Bob Levin made me part of ch. 19 in his excellent The Pirates and the Mouse, which Fantagraphics published some years ago now. It remains an essential resource tool I highly recommend.

My musings around Ted is what comes to mind. Until he disembarked from the comics world circa 1981 for computer games at Atari, I saw him all the time. And, of course, we got stoned when talking and absorbing comics. That, to some of us, is the only way to fly!

Ron Turner

(publisher via Last Gasp)

Ted Richards: as one of the Air Pirates he attained a degree of notoriety, and had they won the case he would have been world-famous. His dad's military background and [his military time] during the Vietnam War gave him a reality and insight that few had at that time. Dopin' Dan comics attest to that. E.Z. Wolf's Astral Outhouse and The Forty Year Old Hippie had quite good humor, but a careful reading would bring out the brutal underpinnings of his intent.

Felix Dennis of OZ magazine fame and a line of British undergrounds had branched off into computer magazines and had Ted doing characters at trade shows. This led him to his turn in Silicon Valley.

We had set up a production studio for Young Lust #3, an all-color underground. Terre Richards needed a place to stay and she moved into the house where I lived in Berkeley. Ted met her at Last Gasp and soon was joining us all in Berkeley. We got together after several decades and were trying to see if we could have all the Air Pirates on a panel for Comic-Con.

This never happened. Sadly.

Terre Richards

(cartoonist, ex-wife)

Ted invented so many different comic personalities, including Dopin' Dan and The Forty Year Old Hippie, as well as his self-referential comic strip E.Z. Wolf's Astral Outhouse. But beyond his underground comics, Ted created characters for the mainstream like Mellow Cat for SkateBoarder magazine. He had a new following of skateboarding kids, the next generation of rebels! It was always an adventure visiting SkateBoarder and meeting some of the famous skaters of the day like Tony Alva. Ted's comix spanned the generations. He had the ability to capture the current culture with clever observations and crazy characters that caught the imagination of the next wave of comics fans.

Miranda Lee Richards

(singer-songwriter, daughter)

As a little girl, I remember my dad at his drawing board, spending many an evening working late into the night. He would listen to talk radio and smoke cigarettes while inking, and I would make excuses to stay up past my bedtime to accompany him: "I'm not tired," or "I want a bowl of cereal" were my usual quips.

This was a magical time in the wee hours, when the world was quiet and he could work undisturbed, minus my occasional interruption. I would get out my drawing pad and practice, alongside him, in awe of his talent and mastery even then. It was obvious to anyone—friends, family, colleagues, fans, and even himself—much to the dismay of a handful of critics and competitors. But he was a wonderful father, especially during that era.

What better human to be guided by, one that was artistically and creatively fulfilled; one who was effortlessly in communion with his own muse.

* * *

A private memorial for Richards will be held at the California Central Coast Veterans Cemetery in Seaside, CA, followed by an event on June 10th at the Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco, CA. In lieu of flowers, contributions toward his estate expenses can be made to his GoFundMe page, now administered by Miranda Lee Richards. Tax-deductible donations can be made to Youth Spirit Artworks for arts-related job training for homeless and low-income youth in the Bay Area.