As Chris Ware’s ambitious Acme Novelty Library #19 opens, a lonely astronaut shaves in his prefab Martian cabin.

This sequence, we later realize, is part of “The Seeing-Eye Dogs of Mars,” a story written by Ware’s protagonist, W. K. Brown. A devoted science-fiction reader, Brown writes what he reads — and what he knows. The romance-adventure plot of his sci-fi tale echoes his real-life drama of unfulfilled romantic longings and alienation, a domestic tragedy Ware takes up in the comic’s second section, after Brown’s fiction ends. To tell both stories, the cartoonist enlists the aid of an unassuming red circle; it debuts in the first panel as a round cap that holds a safety razor’s blade in place.

This sequence, we later realize, is part of “The Seeing-Eye Dogs of Mars,” a story written by Ware’s protagonist, W. K. Brown. A devoted science-fiction reader, Brown writes what he reads — and what he knows. The romance-adventure plot of his sci-fi tale echoes his real-life drama of unfulfilled romantic longings and alienation, a domestic tragedy Ware takes up in the comic’s second section, after Brown’s fiction ends. To tell both stories, the cartoonist enlists the aid of an unassuming red circle; it debuts in the first panel as a round cap that holds a safety razor’s blade in place.

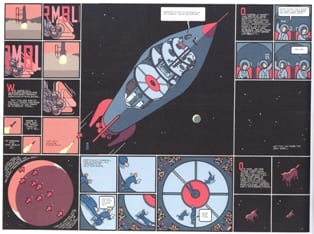

Ware, who has often compared comics to music, uses the red circle as a visual leitmotif, a “short, repeated musical theme” that he associates with Brown and threads throughout the comic’s two narratives. It first appears as the razor’s cap and then as a pushpin holding up photos of the astronaut and his “first and only true love.”

The circle reappears as a part of a space helmet, an entry button to a spaceship’s “shower tube,”

locations of Martian colonies on a map, and as Mars itself. It eventually moves outside of the sci-fi story into Brown’s life, appearing, for example, as the earrings of his “true love” (who doesn’t even like him):

Ware signals his interest in creating relationships between color and character by using last names such as Brown and White. ANL #19’s patterning of red circles links mundane, erotic, and otherworldly objects to Brown’s sci-fi protagonist and to Brown's own interior life. Though tempting, it would be a mistake to interpret these red objects as symbols — they don’t symbolize anything in the sense of “this stands for that.” Rather, they generate an expansive web of objects, telling us about Brown and connecting moments in his life in ways more evocative than explanatory.

In addition to providing thematic consistency (as musical motifs do in a lengthy composition), they also create visual continuity, and even a ‘color narrative.’ Ware’s method allows us to appreciate his pages without reading them; we follow a visual thread based on iterations and transformations of this red character. More so than most cartoonists’ pages, Ware’s layouts are equally successful as narratives and as discrete abstract compositions. Each page’s organized play of colors and shapes stands on its own.

In the real world, our perception of an object’s color is subject to shifting factors of light, shadow, and proximity. What we label a given color is often a complex of different hues. But when we experience Ware’s flat-color paper world — reading a book that remains a steady distance from our face — color is simpler, more consistent. Objects such as the razor’s cap and shower button look forever new, like icons frozen in time. This lack of visual ambiguity gives Ware’s work an unusual internal cohesiveness; it’s as if items of the same color, especially those of a similar shape, ‘ask’ to be associated with each other, interpreted as parts of an organized, self-referential system.

On the above page, red circles become a part of other circles, which seem to transform into still more circles, all of which the cartoonist arranges within a series of rectangular panels, pages, and book covers; the interior front and back covers surround all of the pages, in effect framing them. Along with its design role, Ware’s comics geometry means something story-wise; it reflects the primal, almost irreducible nature of Brown's stunted emotions. Never has loneliness been as starkly beautiful — or as colorful — as it is in Ware.

Perhaps the most important red circles appear when Ware shows five covers of the sci-fi pulps that the young Brown collects and reads; he consumes them with a fevered, almost life-sustaining intensity, especially after his “true love” has revealed herself to him as anything but. Four sport a conspicuous red circle (the alluring red lights of a “red light district”?). This density of the leitmotif amps up the visual tension, alerting us to the pulps’ thematic significance. This page, we realize, must be an important moment, a crux in Ware’s paper symphony:

All the covers flaunt a subtext that the title Spunk (slang for semen) cheekily reveals: they allegorize a fantasy of male sexual domination.

The romantically and sexually frustrated pulp reader identifies with the villain (the reader’s id) as it wields power over a woman. As an id, the villain is free from the anxieties that such urges provoke in Brown, who suffers from a debilitating self-awareness and self-doubt. The naive pulp reader (and Brown couldn’t be more so) likely believes that the covers present moral scenarios that demand heroic action. Like any good Intergalactic Boy-Ranger, he would, without a moment’s hesitation, rescue the distressed damsel. But only in order to do what the monsters are about to do: violate her. (Naturally, she would show her gratitude for his timely intervention.) In the real world, Brown's life inverts the pulp covers’ scenario: he has been captured by a emasculating woman who dominated his body and mind and destroyed his romantic hopes. In the pulps, his problems find their solution: the male takes charge. Identifying with the villain, the reader figuratively reestablishes his mastery, his masculinity.

The “science” part of “science fiction” provides these alluring pulps (and Brown) with a veneer of intellectualism. Their real interest, however, lies in exploring something a little less scientific, a desire that, since it can’t be directly acknowledged, comes dressed up as a colorful fantasy about distant planets, future worlds: the reader’s present feelings must be repressed and channeled into something heroic and inspirational. The physical distance between earth and the galaxy’s planets — between reality and fantasy — serves as a metaphor for the emotional distance between the alienated pulp reader and others, especially women. Ware also indicates this distance by creating a contradiction between Brown’s text and the visual narrator’s image:

Fixated on color (and given his name, why wouldn’t he be?), Brown often changes a female character’s hair color on “The Seeing-Eye Dogs” manuscript, even crossing out “brown” and adding in “rusty.”The text/image contradiction in the above panel implies that the first part of ANL #19 may not faithfully retell Brown’s story. When Ware adapts Brown’s prose into comics form, he undermines the protagonist’s narrative reliability by allowing the comic’s images to tell a truth that Brown’s first-person prose elides.

***

As Acme Novelty Library #19 closes, Brown, long since married to a woman he finds far less compelling than the one he loved in his 20s, is shaving in their home. This middleclass, suburban residence lacks the Spartan romance of the Martian cabin where we began, where we first saw Brown’s sci-fi doppelganger at the sink.

Before shaving, Brown indulges in a fantasy. He masturbates while thinking about his former girlfriend. Does he shave so he can conjure up the intense feelings he felt when young and moustache-less, the sense of excitement and possibility that’s now gone, as he sinks further into an unhappy, unadventurous life?

Perhaps signaling Brown’s humiliation, the red circle appears on the comic’s final page not as something otherworldly (like Mars), but something kitschy: the nose of a pink-bowed poodle on the art that adorns the bathroom wall (surely not a decorative choice that Brown would’ve made):

The last panel of the shaving sequence, and of Acme Novelty Library #19, employs thousands of red circles to form Brown's pale red circle of a nose (the final sign of his humiliation and alienation?). The image is fuzzy and fragmented, like a page of old newspaper comics examined too closely, revealing the dots that build areas of color, the reality behind the appearance.

Here we see Brown emotionally and visually deconstructed. Perhaps this is how he sees himself, not through the ennobling lens of speculative fiction celebrating “mankind’s ceaseless curiosity,” but through his own weakened eyesight after removing his glasses.

Throughout the comic, the young Brown’s glasses (often seen with one lens half-shattered), evoke his powerful disconnect from the real world — he literally can’t see things for what they are.

Despite incontrovertible evidence, the older Brown still can’t (won’t?) see that his first girlfriend never loved him. Or, when he looks in the mirror (a classic way to represent self-realization), has he achieved a new perspective, seeing for the first time that his fantasies have continually failed him? I’m not sure.

With these recurring broken glasses and red circles, Ware creates powerful organizing motifs for the comic and its too-often emotionally blind hero, W. K. Brown, the less-than-colorful author of “The Seeing-Eye Dogs of Mars.”