Matsumoto Masahiko was born in Osaka in 1934. In the summer of 1945, under threat from American bombers, his family evacuated to Kobe. That is the town Matsumoto called home until relocating to Tokyo in 1957 along with the other core members of the Hinomaru cohort.

Matsumoto’s father, a high school principal, hated manga. “My uncle bought a copy of Yokoyama Ryūichi’s Fuku-chan for me,” recalled Matsumoto, “and my father destroyed it right before my eyes. . . . After he died he 1943, I still kept my distance from comics.” When after the war Matsumoto subscribed to Shōnen Club, again it was not for the comics. He says he was attracted to the buoyant youth spirit of the prose fiction, the science features, and the detailed illustrations. The only manga he recalls from Shōnen Club is Yokoi Fukujirō’s Strange World Puchar (Fushigina kuni no putchaa, 1946-48), a SF manga emonogatari starring an atomic-powered robot that informed Tezuka’s Astro Boy.

Matsumoto’s interest in art grew rapidly in middle school. He copied pen illustrations from magazines, and made many regular outings with his school art teacher to sketch and paint from nature. His oil paintings were good enough to win a prize in 1949. He began taking lessons at a municipal art school in Kobe. His education there appears to have been in the classical Western mode, centered on drawing from plaster casts and quick croquis sketching of live nude models.

“And that’s when it happened,” says Matsumoto. A friend in his art class introduced Matsumoto to Tezuka’s books. And as was the case for so many other boys of his generation, the introduction turned into a love affair, and the love affair gave birth to dreams about becoming a cartoonist. Since this was in 1949-50, Matsumoto’s first contact was a mix of Tezuka’s earliest akahon (probably in hardcover reprint) and the better-drawn and better-produced, slightly later volumes from legitimate Osaka and Tokyo publishers. The titles Matsumoto recalled checking out from his local rental bookstore included The World 1000 Years Later (Issen-nen ato no sekai, 1948), Man of Tail (Yūbijin, 1949), The Wonderful Journey (Fushigi ryokōki, 1950), Next World (Kitarubeki sekai, 1951), and A Trip to the Moon (Getsu sekai shinshi, 1951).

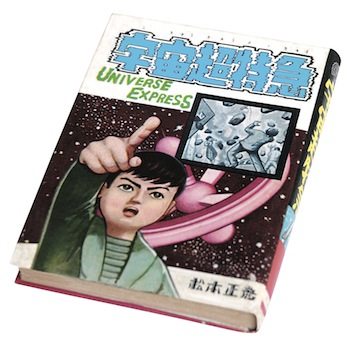

In 1951, Matsumoto went to the offices of Tōkōdō, one of Tezuka’s publishers in Osaka, in search of the artist’s address. He succeeded in getting it, and called on Tezuka at his studio in Takarazuka, leaving with a signed drawing and the conviction to create his own comic book. Soon after, Matsumoto drew When Worlds Collide (Chikyū no saigo, 1952), a heavily Tezuka-esque, book-length SF adventure. Like the novel and movie after which it was named, Matsumoto’s When Worlds Collide too narrates the approach of a planet on a collision course with earth and the humans’ desperate attempt to escape by rocket ship.

For a taste of the period, here is Matsumoto: “Around 1950, the postwar akahon boom had finally dropped a notch. It was a transitional period, readying to switch over to the kashihon boom. The rental bookstores I went to were mainly patronized by adults. There were few comics on the shelf. Amongst those from Tokyo publishers that I remember were works by Matsushita Ichio, Shimada Keizō, and Noro Shinpei. Akahon from Osaka publishers, meanwhile, had a cheery and anything-goes feeling, like a box of toys flipped over and dumped out. Most of those artists had been drawing since before the war, like Ōno Kiyoshi and Sakai Shichima, and their art looked it. It took about three or four years for the postwar generation to emerge on the scene. Reading cartoonists other than Tezuka only made me realize how great Tezuka was. Rather than a comic whose story goes from laugh to laugh, Tezuka was interested in the story itself. He developed stories that were not dependent on laughter.”

This emphasis on story versus humor became a central part of Matsumoto’s komaga theory, as it did Tatsumi’s gekiga theory. Here it’s worth noting a separate feature of Matsumoto’s rookie work. The characters of When Worlds Collide are all tall and relatively naturalistically proportioned. Tezuka, at this point, was approaching the peak of his Disney style. There are still some long-limbed characters in his work, but bodies were getting increasingly compact under the influence of Floyd Gottfredson and other Mickey Mouse comic book artists. The elongated characters of When Worlds Collide might reflect the influence of slightly earlier Tezuka manga like The Mysterious Underground Men (Chiteikoku no kaijin, 1947)or Lost World (Rosuto waarudo, 1948). They look somewhat like the human characters in Tezuka’s pre-debut work, but Matsumoto could not have known about these. They might reflect Matsumoto’s inability to caricature in an effective way, something that would contribute to his eventual usurpation by Tatsumi. But considering that Matsumoto, in his komaga work, would take this type of figuration and, instead of squashing characters and situating their center of gravity (Disney-style) in the gut, put it in their legs and feet in order to plant them more firmly within perspectival spaces where they are subject to heavy foreshortening, it is worth remembering that Matsumoto first came to drawing through naturalistic illustration and classical art lessons. Cartooning came afterwards, and thus had to contend with a competing set of artistic principles.

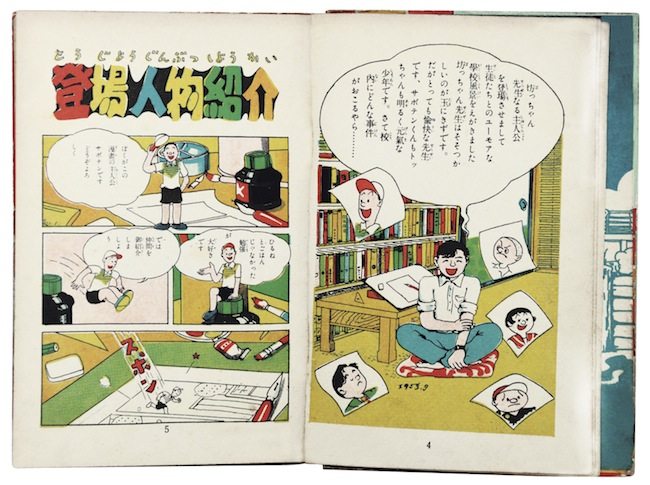

When Worlds Collide did not appeal to Osaka publishers. Matsumoto took the manuscript to Tōyō Shuppansha, a new kashihon publisher that later, after changing its name to Hakkō, would publish the seminal komaga and proto-gekiga works as part of its Hinomaru Bunko series. “Westerns and science fiction don't sell,” Matsumoto was told abruptly, expressing how the Americanized fads of the Occupation era had passed. Tōyō was impressed enough with Matsumoto’s abilities to invite him to draw something else, something funny. He came up with a schoolhouse comedy starring two sixth graders, a beanpole named Saboten (Cactus) and a runt named Totchan, who were inspired, claimed Matsumoto, by Abbot and Costello.

Published in October 1953, Botchan Sensei was Matsumoto’s debut book. It was popular enough to warrant a sequel. A third book in the same genre, Humor School (Yūmoa gakkō) appeared in early 1954. This was Matsumoto’s first contribution of many to the famous Hinomaru Bunko series. If Matsumoto made the rejection of humor a core principle of komaga, it is important to remember that his professional career as a cartoonist began by being forced to create schoolyard slapstick. As soon as he stopped drawing in that genre, the first real portents of a new kind of art appeared.

(cont'd)