The proliferation of trains and train crossings in Matsumoto’s work was first noted by gekiga scholar and former Ax-editor Asakawa Mitsuhiro. In an essay accompanying a 2009 collection of Matsumoto’s komaga from Shōgakukan, Asakawa explains the recurrence of this motif, and the palpitating “excited feeling” (wakuwaku kan) that often accompanies it, through reference to Matsumoto’s personal life. Apparently Matsumoto’s original home in Osaka, and his second home in Kobe, were both near train tracks. “This is just a hypothesis,” writes Asakawa, “and I don't’ really have any solid proof, but going back to his childhood when his father was still alive, I wonder if the other side of the train tracks represented a place where something or someone he loved was located.” The “realism” of komaga and gekiga is a common theme in Asakawa’s writing, and this explanation of train crossings fits into his wider concern with how Matsumoto’s work created a closer correspondence between manga and everyday Japanese life through references to postwar poverty and hardships experienced during the war.

Whatever personal resonances they might have had, trains and train crossings were clearly not just sentimental motifs for Matsumoto. Their sheer frequency alone suggests that they made a natural fit with komaga’s formal system of metered breakdowns. Asakawa also notes that train crossings served as an opportunity for Matsumoto to “change viewpoints far more than was necessary for the purposes of the story.” I will have more to say about viewpoints next time. But I think this excess can begin to be explained by first recognizing that the train crossing is a special kind of clock – a clock with two faces, so to speak, one regular and one spatially warped.

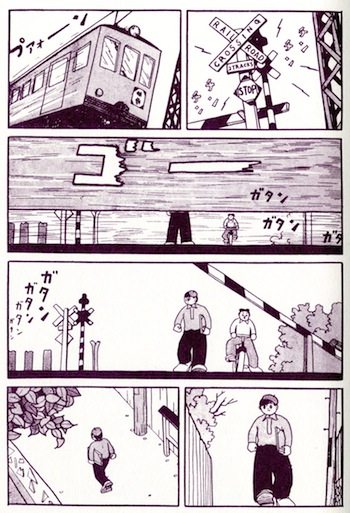

Matsumoto often takes care to depict train crossings in detail. Typically, the mechanism has just been activated. The guard bar lowers. The signal makes a dinging that is both regular and loud. If wall clocks and wristwatches require coupling with an approaching event to serve as vehicles of suspense, that function is built into the train crossing: its regular measuring of time is precisely for the purpose of warning people of an approaching danger. A pure form of this would be a time bomb. But this is where it is essential to recognize that the train crossing, unlike the time bomb, which is nothing more than a clock that explodes at the witching hour, combines two spatial modalities of time.

The train crossing is not just the signal mechanism alone. It is not just the guard bar and the alarm signal. It is also the oncoming train. Isolated, the signal mechanism provides the image and sound of regularly metered time – ding ding ding ding ding ding ding – fixed in space like a clock on the wall. The approaching train, on the other hand, as a moving object, embodies a spatial modulation of temporal experience: it shows how the experience of time is modified by spatial change. Though the train runs at a fixed velocity, what is typically depicted in Matsumoto’s comics is the experience of the train’s movement from a fixed spot outside the train, namely from the position of a person waiting at the train crossing. That experience, of course, is subject to a combined perspectival and Doppler effect in which the image and sound of the train changes in magnitude as the train approaches and then recedes from the viewer. And as it changes in magnitude, so its effect on the viewer – the diegetic viewer and the reader alike – also changes in magnitude.

Recall the chronoscopic passage of The Mannequin Gentleman. There, as discussed above, clocks were deployed to recreate, not regularly metered time in breakdown form, but rather the phenomenological sensation of anticipation, which it did via decreasing temporal intervals. What interested Matsumoto in the train crossing, I think, is that it captured these two forms of temporality in a single physical form found in the everyday world. The activated train crossing combines the reverberation of regular clock time (the signal mechanism) with the anticipatory quality of phenomenological time (the approaching train). This was not a philosophical abstraction for Matsumoto. It was essential for him, as a suspense author, that the intersection of these two temporal modalities spells oncoming danger (that of being hit by the train). Whatever warm sentiments train crossings might have held for the artist privately, as far as Matsumoto’s work is concerned they primarily signify a threat.

It is thus that, a year later, in a work like “The Man Next Door,” a page showing a man peacefully crossing the tracks with a smile can serve seamlessly as a segue between one page filled with anger and expletives and another in which that same enmity is directed at the carefree track-crosser, utterly spoiling his mood. Even if a Matsumoto character clears the train crossing itself without fear or injury, he is still liable to be hit with threats to his life and happiness on the other side.

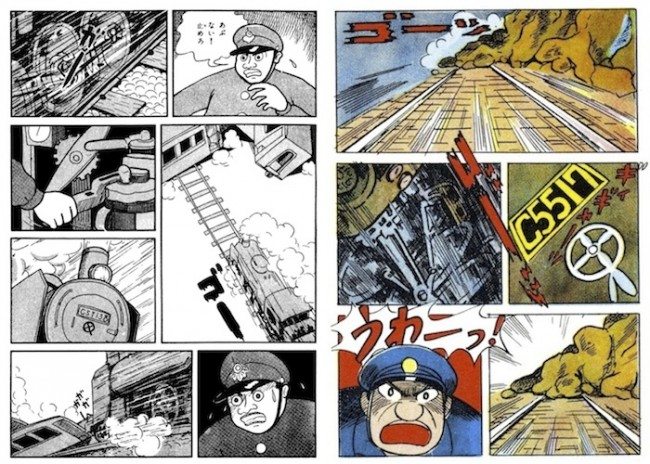

Not surprisingly, more than a few fatal train accidents occur in Matsumoto’s work. But judging from the comics I have seen, such accidents proliferate slightly later in his career, around 1956, at a juncture in which chronoscopia and suspense alone no longer satisfied kashihon mystery’s obsession with negative affect. One might take the “realist” approach and point to the fact that train accidents, like airplane crashes today, were not only a common occurrence in 50s Japan, but invested with tragic and political import far beyond the losses they actually inflicted on human life and society.

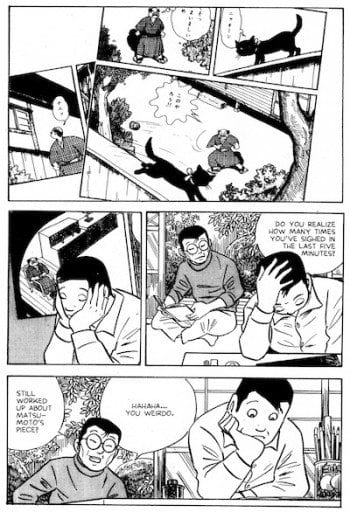

The newspapers in “The Cat and the Locomotive” (November 1956, translated in Breakdown’s The Man Next Door) indicate that Matsumoto was keenly aware of these disasters. But given that the moving trains is an integral formal device in komaga-gekiga’s manipulation of temporal experience, one might look at the train catastrophe from the other side, from the vantage of Matsumoto’s aesthetic system, and say that, through the train catastrophe, characters are made to suffer for the fact that the author’s formal experiments occurred in the service of the specific genre of mystery. Spatially-modulated time in Matsumoto’s work was as a result always already inscribed with anxiety or other unpleasant phenomenological effects. In other authors’ hands, the chugging steam engine expressed the ambivalent emotions of moving between country and city. In contrast, throughout Matsumoto’s kashihon years, the hurtling train represented warped time exaggerated in its negative affective dimension.

Here is where more detailed archival research is necessary: if komaga’s chronoscopia dictated that the train threaten, then only after shock and tragedy began to commandeer suspense and anxiety within Matsumoto’s work did it become necessary for the train to also crash and kill. At that point, we see a fundamental shift in kashihon mystery. It is probably no accident that “The Cat and the Locomotive” and Tatsumi’s Black Blizzard (a work that not only deploys komaga’s chronoscopia generally, but also swipes specific motifs from Matsumto’s comics) both begin with train wrecks and that both were published in November 1956. We might describe this shift generally as the absorption of komaga by gekiga. But how to explain the coincidence historically, beyond reference to the fact that Matsumoto and Tatsumi, with Saitō Takao, had been living together in the same apartment just prior to these works’ publication?

For now, let’s stick to komaga in its classical phase. What Matsumoto’s chronoscopia and manipulation of different modalities of time shows is that the “synchronization of time and space” that Tatsumi claimed for gekiga was, in fact, quite a complicated matter. Both he and Matsumoto identified the increased space allowed by book-length page counts as the necessary physical precondition for their experiments: it allowed for freer pacing and the exploration of psychological effects enabled by such pacing. The essential question is: How did the two cartoonists exploit this page count differently?

The example that Tatsumi’s typically gives is a page from his The Demon of Civilization (Kaika no oni, September 1955), showing a man on a moving rickshaw who draws his sword and attempts to cut down his driver. For comparison, let’s trot out another scene from Tezuka’s transitional Crime and Punishment. The page I have in mind shows an overfilled, horse-driven wagon upon collision with a drunk in the middle of street, causing the wheels to break and the cart to collapse in a sequence of three cramped and cacophonous panels. One might argue that Tatsumi shared Tezuka’s interest in noise and abstracted detail, certainly more than Matsumoto did. But clearly Tatsumi’s famous proto-gekiga page is based on study of komaga chronoscopia: the metaphorical clock of the rickshaw’s rattling wheels, passing time as approaching danger, the montage of details as a visual echo of anticipatory intervals, and (something that is particularly evident when juxtaposed against the Tezuka example) the divorce of physical violence from slapstick, in other words intensified sensation and affect from humor.

With a view to the important question of what differentiates gekiga from komaga, notice both what Tatsumi has added to Matsumoto’s system and what he has subtracted. He has added a greater emphasis on sensation through sharpened pulse-like details and visual and aural noise. He has abstracted suspense’s intensity to create an image of purer energy and affect. As for what has been subtracted, he has, if not eliminated Matsumoto’s Doppler-type warped time completely, lessened it significantly. The intervals do not noticeably decrease as anticipation grows. There is no clock or any other metering device to even compare one panel’s duration to the next reliably. And significantly, the man at whom the sword is swung is the rickshaw’s driver, who is moving with the assailant at the same speed and in the same direction. Both characters ride the same “train,” so to speak – they are on the same clock. There is no evident interest here in how space modulates the experience of time.

One can see here one of the fundamental differences between Matsumoto and Tatsumi. Both artists were attuned to the phenomenological qualities of temporal experience – had they not been, kashihon mystery manga would have ended up a boring parade of filmic breakdowns and actual or metaphorical clocks – but each did so differently. If Matsumoto focused on the relationship between time and space, Tatsumi was more interested in the relationship between time and energy, leading to intensified sound effects, visual wakes, pulse-like panels, and animated cartooning. It is because of Matsumoto’s central concern with space that one sees in his work an interest in how temporal metrics are modulated spatially in the form of approaching dangers, like thieves, killers, or trains – motifs that Tatsumi inherited from komaga. Hence also Matsumoto’s obsession with super low angles and extreme foreshortening, both of which are noticeably rare in Tatsumi’s spatially flattened work.

Next time, I will consider how Matsumoto’s famously exaggerated sense of space fits within his system of metered breakdowns, and how it relates to judo manga and a mid 50s fascination with cinematic spectacle and 3D.