Today on the site, Michael Dean has our obituary for Supernatural Law creator Batton Lash.

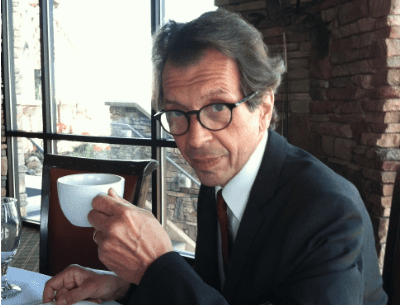

Wolff & Byrd creator Batton Lash died Saturday at the age of 65 after a two-year battle with brain cancer. Though he was never a star of the comics mainstream, the announcement drew a surge of web posts from fans and independent comics creators who knew Lash as a friendly and supportive presence at comics conventions.

Born in Brooklyn in 1953, Lash attended New York’s School of Visual Arts, where he studied under comics legends Will Eisner and Harvey Kurtzman. After graduation, he did illustrations for such publications as Garbage magazine and the book Rock ‘n’ Roll Confidential and worked as an assistant for comics artist Howard Chaykin. Invited in 1979 to contribute to newly launched newsweekly Brooklyn Papers, Lash noted that the area where the broadsheet was distributed included a concentration of courts and law offices: a prime audience for a humorous strip about the law. His Wolff & Byrd, Counselors of the Macabre followed the case files of Alana Wolff and Jeff Byrd, whose legal practice specialized in supernatural and super-powered clients. Both gothic and cartoonish, Lash’s art reflected the influence of his mentors by combining realistic detail with expressive caricature. The strip ran in Brooklyn Papers until 1996 and, in 1983, was picked up by the National Law Review, where it continued until 1997.

Edwin Turner is here, too, with a review of Paul Kirchner's Hieronymus & Bosch.

Paul Kirchner's Hieronymus & Bosch collects over eighty comic strips that riff on the afterlife of a "shameless ne'er-do-well named Hieronymus" and his faithful wooden toy duck, Bosch. The hapless pair are trapped in Hell, the primary setting for most of the strips (although we do get a bit of heaven and earth thrown in here and there). Kirchner's Hell is a paradise of goofy gags. The one-pagers in Hieronymus & Bosch cackle with burlesque energy, propelled by a simple plot: our hero Hieronymus tries to escape, fails, and tries again.

And what sins have damned poor Hieronymus to Hell? When we first meet the cloaked miscreant he's passed out, drooling all over an altar, clearly having enjoyed too much communion wine. An annoyed bishop prods him awake and kicks him from the church doors and into the village, where he proceeds to sin his ass off. Kirchner's Hieronymus doesn't quite fit all of the seven deadly sins in this morning (those same sins that the historical Hieronymus Bosch captured so well in his famous table), but he comes pretty damn close. Notably, he steals his comrade Bosch--a toy duck--from some poor kid. The wages of sin are death though, and poor Hieronymus, in a fit of wacky wrath, slips in some shit, falls on his toy duck, and careens into death.

Bad news: He's in Hell, where hope is strictly prohibited.

Meanwhile, elsewhere:

—Reviews & Commentary. Maria Bustillos reconsiders what is possibly Saul Steinberg's most famous images (and interviews David Remnick about it).

I was looking into this drawing because it had dawned on me recently that I’d never quite understood the joke. Was it “Oh New Yorkers! they think they’re the center of the world!”?? Or was it, “Well, it’s funny that they think that but also they are, right? ha-ha!” I saw in it a poking fun at the paradox, the small-mindedness of “cosmopolitanism.” Maybe, the artist’s little joke against himself.

Was I ever wrong! Not one person whom I’ve asked about this drawing understood what Steinberg meant by it, even though the answer is written plain as day in the weird and excellent 2012 biography by Deirdre Bair—and still more clearly in the image itself, once you know how to look. It turns out the answer matters, too; it matters a lot.

Brian Nicholson looks at Alack Sinner.

In the story “Life Ain’t A Comic Book, Kid,” two comic creators, Muñoz and Sampayo have discovered that there’s a real detective who shares a name with their fictional detective character, so they visit New York to meet him. It’s for comic relief, mostly, but crime fiction doesn’t really traffic in this level of fourth-wall breaking. There are arcs of Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips’ Criminal and Rich Tommaso’s Dry County that work the job of a cartoonist into a crime plot, but that’s those works being beholden to the tenets of realism, and using autobiographical lived experience for verisimilitude, which isn’t the goal here. Instead, it creates a space for the cartoonists to say, explicitly, to their main character: “Yeah, you’re an honest man and you don’t kill people, but you’re still an American, and so complicit in a system that exploits the rest of the world, so we are not cool.”

Dana Forsythe revisits the well-trod but always worth revisiting story of Love & Rockets.

Groundbreaking, epic, and heartfelt, the quintessential indie comic Love and Rockets is as relevant today as it was when Mario, Gilbert (aka Beto), and Jaime Hernandez self-published the first issue in 1981. A blend of sci-fi, telenovela, superhero tales, comics, jokes, and short stories, the magazine was worlds away from anything anyone, especially Marvel or DC, was publishing during those days.

Not only did Love and Rockets usher in a new age of independent comic books, but it also broke ground with stories featuring marginalized voices and characters from the LGBTQ and Latinx community. By the time DC and Marvel had introduced Latinx characters like Sunspot, Firebird, and Bushmaster in the early '80s, Margarita Luisa "Maggie" Chascarrillo, Esperanza "Hopey" Leticia Glass and the fiery Luba were living out real lives in the fictional towns of Hoppers and Palomar in Love and Rockets.

—Crowdfunding. Carol Tyler has launched a Patreon.