Thoughts and impressions on a selection of noteworthy comics I've recently read.

* * *

BILL PEET: AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY (Houghton Mifflin, 1989) - Bill Peet

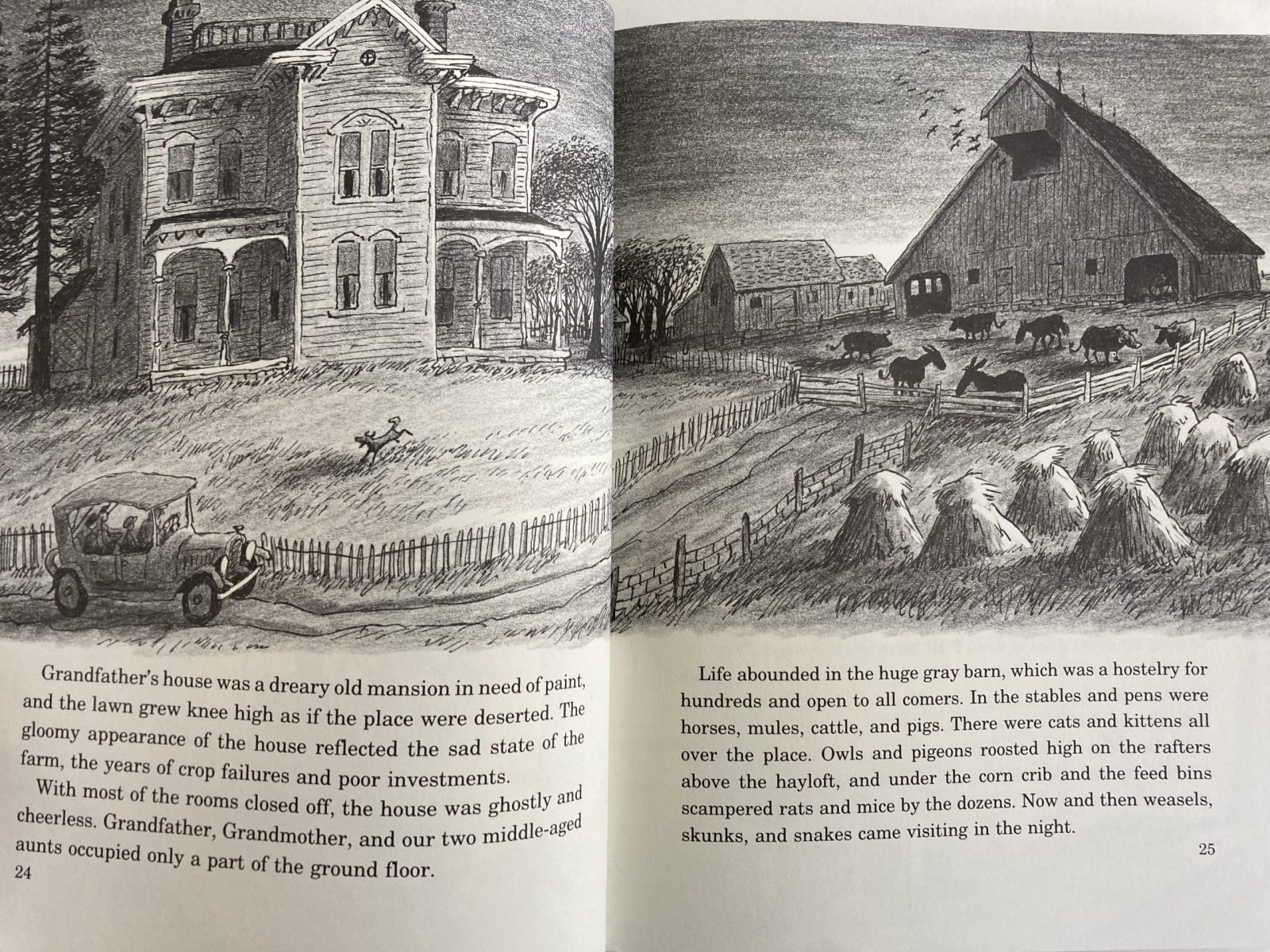

When I stumbled onto this in a bookstore it was love at first sight. It’s such a big, beautiful, generous thing. It’s also kind of an odd duck: it’s got the illustration density and wholesome, straightforward voice of a children’s book, but the page count and subject matter of an adult autobiography - it’s endearingly unclassifiable. I wondered, while reading it, if Peet used this format to deliberately appeal to young people, or if he was just so accustomed to the format that this was the best way for him to get his story down. I read an interview with him after finishing this book which didn’t answer that question, but did reveal part of the impetus behind the book as setting the record straight about his time at Disney, which takes up almost all of the book’s second half. (I'd only known Peet as a children’s book author when I picked this up; the Disney stuff was a pleasant surprise.) Reading the book, you get the sense that Disney was a pretty frustrating place to work, but Peet's authorial tone is so gentle it’s hard to gauge the nuance of his displeasure. Reading the interview, though, he’s very openly bitter about the people he worked alongside, whom he paints as almost all a bunch of rotten, back-stabbing, credit-stealing assholes. He also, naturally, endeavors to take credit for a bunch of stuff that he can’t prove one way or another, but it seems believable enough. Maybe as a fellow storyboard person, I’m inclined to side with him in his assessment that storyboarders are the backbone of the whole operation, and whatever credit they get, it’s never enough!

In terms of pure bang-for-your-buck value, this thing might be the best $5.00 I’ve ever spent. It’s 190 pages, and every single one of them has at least one illustration, often two or three, all of which are just amazingly, humbly, elegantly perfect. Peet makes it look not just easy, but fast and fun too. It makes me want to pick up a pen and draw, rather than just drool with awe, which is what his more polished children’s book illustrations make me want to do. As mentioned, the second half mostly covers his time at Disney (he was there from age 22 to age 49), and the first half mostly covers his boyhood. The drawings in the first half are the most consistently stunning: lots of countrysides, farmyards and locomotives. When he gets to LA, everything turns drab and ugly, and he’s indoors most of the time (this particular downgrade hit close to home…). The recurring images that come to mind from the second half are dim offices cluttered with storyboards, and a hunched and fuming Walt Disney stomping around. But it’s leavened by tons of depictions (recreated in his later style) of all the great stuff he created over those 27 years. Peet had a hand in more Disney films than I can list, but had a really big role in 101 Dalmatians, The Sword in the Stone and The Jungle Book. His post-Disney career gets only a handful of pages, his wife and children get almost no mention whatsoever in the entire book, and he does not mention any sort of adult activities, pastimes or hobbies outside of drawing or writing. In fact, I don’t think Peet depicts a single moment of adulthood that doesn’t directly involve his career. The two motivational poles of the book’s creation seem to be nostalgia for the simple, rustic landscapes of his youth, and justified-seeming score-settling. Both of which are more than interesting enough to excuse the narrow focus. Lovely book.

* * *

HARUM SCARUM (Fantagraphics, 1997) - Lewis Trondheim, colored by Brigitte Findakly, translated by Kim Thompson

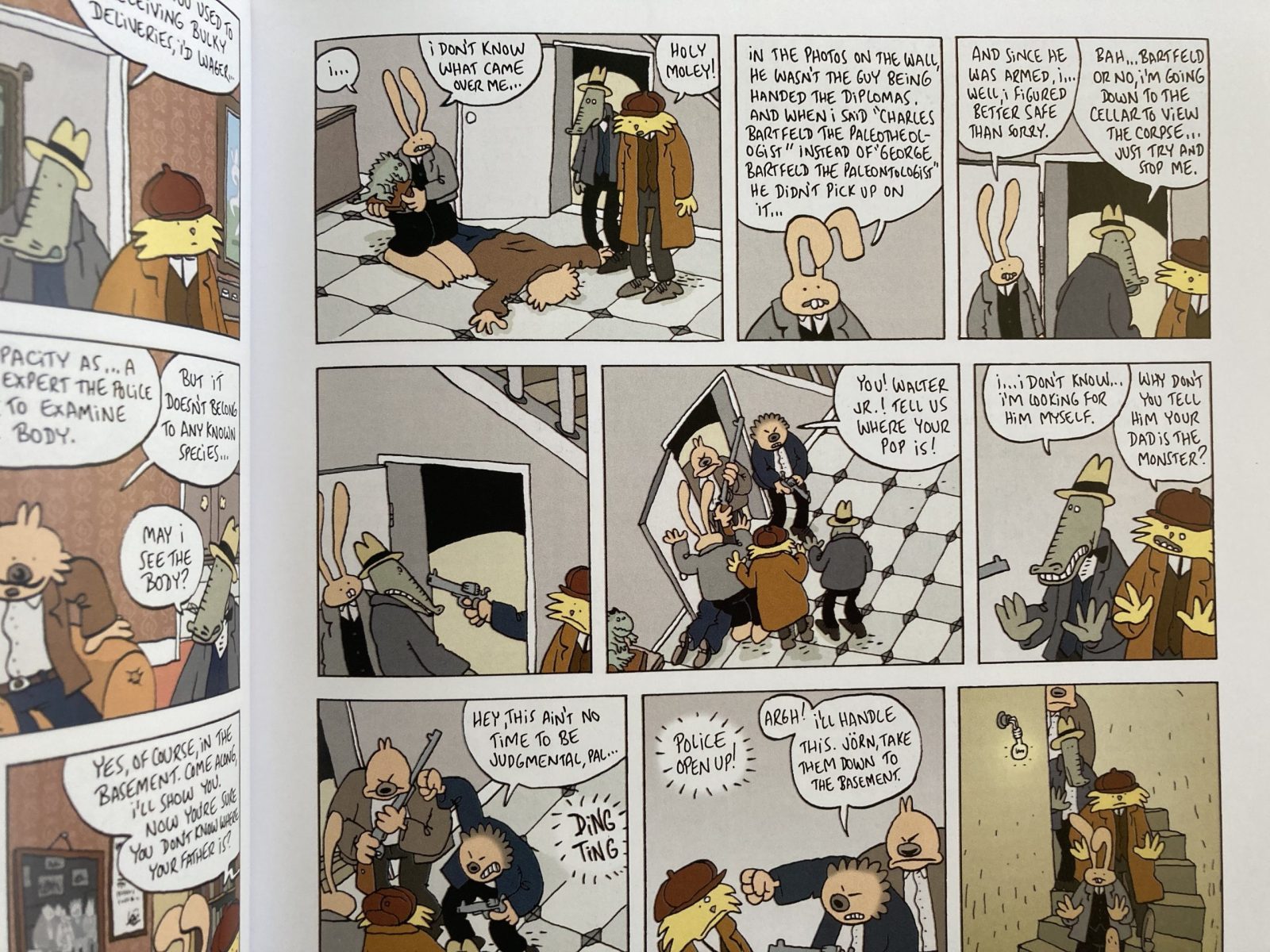

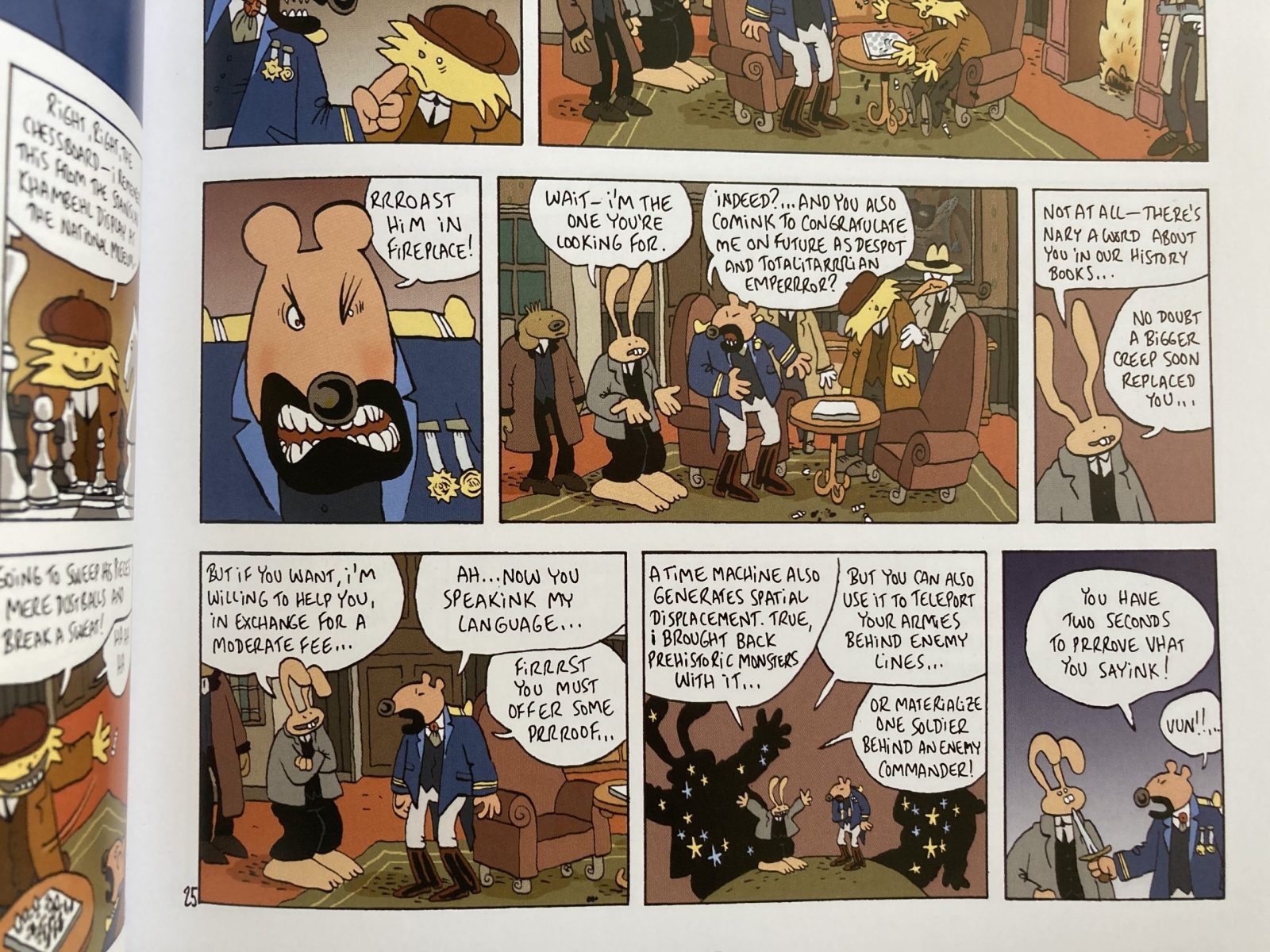

I love the Dungeon books, though there’s so many I quit trying to keep up a long time ago (plus my mileage varies a lot according to who’s drawing them). I’m not sure how Trondheim and Joann Sfar handle the writing, but Trondheim drew the first couple volumes himself. His drawing can be a bit simple and perfunctory-seeming, to put it gently, but in spite of myself I’ve got real affection for it. In part, I think, because I respect his writing so much, and in part because he compensates for the simplicity with uncommon good taste and restraint. It’s like the old Woody Allen line that 80% of success is just showing up: likewise, simply NOT drawing in a cheesily over-stylized manner will let you blend unobtrusively with the cream of European comics draftspersons…

Years ago, I read the first volume of Ralph Azham, Trondheim’s solo fantasy series, and loved it. (Fantagraphics only translated one volume at that time, but Super Genius will have started a new line of translations by the time you’re reading this.) In that one, and this one, Harum Scarum, he’s working in kind of a meat-and-potatoes genre entertainment mode, but doing a really clever, idiosyncratic job of it. All the setups and payoffs have an intricate, clockwork logic to them. Characters are all distinct and well defined - they get right up to the edge of archetypes, but never quite cross it. Or maybe it’s more like they’re Trondheimian archetypes – he seems to gravitate towards good-hearted smartasses, with an angry guy thrown in to get annoyed with the smartass guy, but they’re all baseline reasonable, competent people, which I appreciate. He also gravitates towards satisfyingly inventive physical comedy. There’s a nice scene in this book where the three heroes get captured by some henchmen, then one of the heroes, Inspector Ruffhaus, starts doing the old clichéd routine of acting over-the-top angry towards his friend, eventually pushing that friend, McConey, into one of the goons. When the goons lock the heroes up and leave, Ruffhaus reveals that McConey had already bumped into the goon once before, and had secretly stashed a pistol in the goon’s pocket, and now, with the second bump, McConey has retrieved the gun. At this point I went back a few panels and confirmed that yes, in a little visual sleight of hand, Trondheim does show McConey bumping the goon earlier, and his hand is carefully drawn entering the goon’s pocket, which you’d never notice if you hadn’t known to look. When I resumed reading, and after all that buildup, McConey dryly mentions that he doesn’t have the gun because Ruffhaus pushed him into the wrong goon the second time. Then I was amused to realize that the similarity of the two goons, which I’d noticed but not thought anything of, was another little artfully lain piece of the mechanism. If you think about the scene for a second, it doesn’t really work–the goon would’ve immediately noticed the weight of the gun in his pocket–but for whatever reason it doesn’t feel like a cheat. Partly I think it’s the cartoony drawing, but partly I just appreciate how much creativity Trondheim can muster out of one slightly bent rule. Makes you feel impressed at the effort when the gun later comes back into play, rather than feel nitpicky about the cut corners.

One downside to all this clockwork plotting is that some of the characters felt a bit more like cogs in a machine than people - as though whatever traits they’ve got are just there so they can fit in with the surrounding cogs and keep the mechanism ticking. Like, such and such guy needs to be really thin-skinned so that when he gets insulted at such and such time he reacts in such and such way. That sort of thing. But my only real complaint with this whole volume was the ending, where Trondheim goes overboard with the rule-bending and ends up with plotting that works according to the set-up/pay-off machinery, but is too abrupt and implausible to satisfy.

* * *

ADVENTURES OF CRYSTAL NIGHT (Kitchen Sink, 1980) - Sharon Rudahl

This is a very attractive package - one for the coffee table (even though it’s just a humble comic book). Every square inch of it is teeming with Rudahl’s extremely appealing, weirdly slick, wiggly cartooning. I can’t put my finger on it but it feels ahead of its time somehow - they’re like mid-'90s drawings in a 1980 book. Anyway… they’re really great drawings. I can feel her coming at every single panel with entirely fresh fervor, in a sort of decision making vacuum - everything thrown out and rebuilt anew without reference to the panel before (in a good way). Especially the black and grey spotting, which is unbound by much external consistency, but still feels exactly right and contributes greatly to the electric liveliness of the pages. I had a rough time with the story though. It’s got a simple, fairytale shape, and is interesting enough in the abstract, but is extremely compressed and wordy, and so stuffed with plot that there isn’t room for much else.

In a future society split between extreme haves and extreme have-nots, a curmudgeonly rich woman, inspired by her grandmother’s stories about Kristallnacht, adopts her poor servant’s baby and raises the girl alongside her own daughter. The adopted daughter (Crystal Night) is the stronger, smarter and more rebellious of the two (and the less Aryan). She’s eventually responsible for upending the old social order to clear the way for a more equitable future… The End. Sensible enough, except for a few odd wrinkles. Out of frustration with her adoptive mother’s strictness and abuse–in exchange for his help concealing Crystal’s illegal adoption, the mother signs Crystal up as an aristocrat’s sex slave for six months–she lashes out at her fair-haired, sensitive sister (who’s been risking her own freedom to give aid to the poor) by turning her in to the police and derailing her life. Crystal eventually becomes a politician and uses her power to force through some improvements for the poor, but her plans are completely co-opted and she ends up making their lives much worse. Then, conveniently, a little alien blob she freed from a school science lab when she was a child shows up out of nowhere, now grown huge and invincible, and reveals itself to be an emissary from a powerful alien culture that will reshape human society for the better if Crystal asks it to, or just put things back to how they were before the blob creature inadvertently caused a bunch of Kaiju-style damage, if that’s what she’d prefer. She decides to trust it and the story ends, except for a coda where we see that things still aren’t all that great in the new agrarian society. Any lesson or idea that seems to be suggested somewhere in the story is systematically neutralized by some other part… it all left me feeling sort of blank. Maybe it’s one big allegory? The alien blob thing is the United Nations, and the new society it creates is Israel? I feel like I’m on the right track but I don’t know enough history to try to pick it apart. It would explain the weird shaggy dog structure though. Anyway, to recap: all this would be fine if there were more breathing room to break up the rapid-fire events. It’s plot overload. Gorgeous, though.

* * *

FORBIDDEN SURGERIES OF THE HIDEOUS DR. DIVINUS (Floating World, 2020) - S. Craig Zahler

A quick preamble before I dive in:

I’ve seen the three movies Zahler has written and directed. I liked Bone Tomahawk, I love Dragged Across Concrete (a little cruel for my tastes though), and I really, REALLY love Brawl in Cell Block 99. It was surreal to learn that Zahler was publishing a graphic novel, and even more surreal to learn from his interview on this site that he intends to make at least two more (his second is due out soon). In that interview he seemed pretty much immune to self-doubt or embarrassment - if people thought the book looked amateurish, he seemed completely unbothered. And Dr. Divinus did look pretty amateurish in the previews I saw online. And so I felt drawn to check this out, but anxious too, knowing that it was going to be a potentially disillusioning experience. (I don’t think I SHOULD feel disillusioned if a writer/director I admire turns out to be a less-than-stellar cartoonist, but I might anyway.)

And now that I’ve read it, what’s the verdict? Pretty entertaining. It probably won’t change your life, but it was hard to put down. It’s like a very lean, concise telling of a nasty, goofy, over-the-top horror movie, but with (unsurprisingly) some unusually snappy, inventive tough-guy dialogue throughout. There’s some awkwardness in the cartooning language–mostly it’s redundant scene-setting captions and redundant “telephone” symbols drawn into dialogue boxes–but it’s totally readable. The artwork is the weakest part, but he’s got good taste, so the weakness is mostly just in the stiffness of the anatomy and clumsiness of the foreshortening, not in any sort of decorative self-indulgence. If any other late-40s aspiring cartoonist showed me this, I’d probably tell them to try their hand at screenwriting, but Zahler seems like such a studious, committed guy - I’m very curious to see where his cartooning chops end up.

There’s two kinds horror movies (at least two? maybe just two?): the kind where the protagonists face an incredible evil and, against all odds, defeat it, thus reaching the pinnacle of heroism; and the kind where the evil is so strong that the protagonists do their best, but are basically doomed from the start. (Hostel, which gets a bad rap and is way less disturbing than the ubiquitous Taken, is a good example of the former, though the beginning of Hostel 2 retroactively transforms it into the latter.) I’m a big fan of the “heroic” kind, not such a big fan of the “doomed” kind. Maybe it’s my personal experience combating my own fatalism that makes me bristle any time an author doesn’t sufficiently reject it, but this latter kind of horror story always leaves me with a flat “okay, now what?” sort of feeling. Divinus is of the “doomed” variety, but a crueler variant, where the protagonist doesn’t actually die, but instead winds up imprisoned and consigned to endless torment. It happens so abruptly here that it almost feels like the rest of the story is missing - the escape attempt or the rescue… the story-organ in my brain was crying out for more of a fight after all that buildup. But still - a fun, interesting ride.

* * *

WINGING IT PART 1 OF 2 (Solo Productions, 1988) - Roberta Gregory

Right from the start, every character in this story is acting sort of “off”. It’s the off-ness of, say, discovering E.T. in some bushes and calmly saying “Are you an alien? That’s strange. Where are you from?” And E.T. calmly responds “I’m lost, I need to get back home,” etc. etc. The plot moves in the right direction, but something’s not quite right. It’s the kind of radical, unquestioning acceptance of one’s situation that only happens in dreams. This initially seemed like sloppy writing, since the first few scenes of the story were so simple and familiar–a woman meeting and arguing with God (a giant white-bearded man) and then the devil (a horned, cloven-hoofed monster)–but my author-faith stirred to life as the scenarios got stranger and more inventive. And there is a potential justification lingering in the background: the protagonist attempts suicide in the first few pages, and everything that happens after could actually be some kind of dream. I was occasionally able to experience the effect as “characters acting intriguingly strange” rather than “characters acting unconvincingly human”, but only in fits and spurts. I’m not sure it’s evidence for or against the intentionality hypothesis, but there is one moment where the heroine goes extra far in her “radical acceptance”, getting excited about a possible alien invasion, and how interesting it would be, and another character has to remind her “This is all REAL LIFE.”

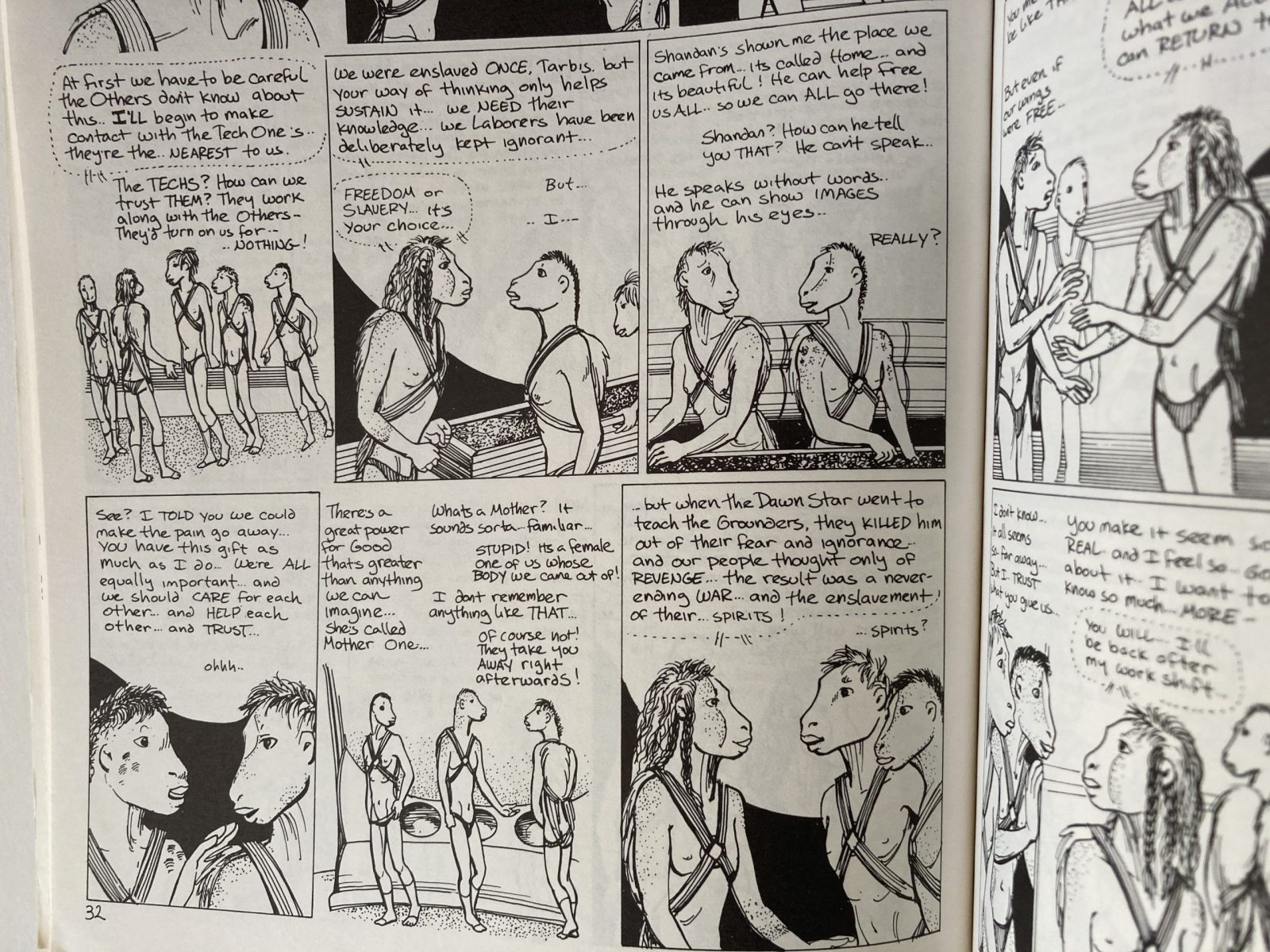

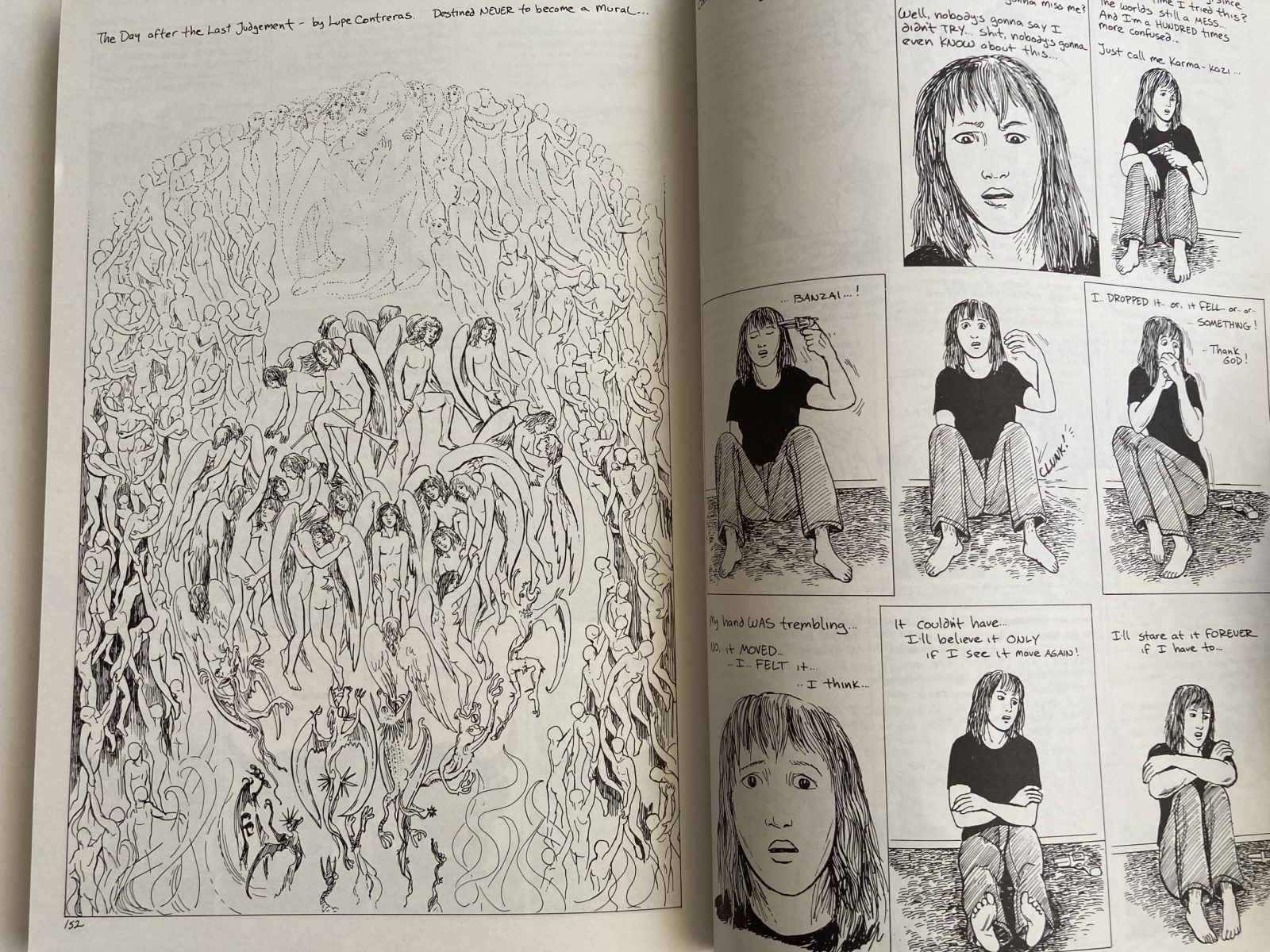

The story shifts back and forth from the woman (Lupe) and an angel she meets early on, to an alien she also meets early on, who is part of an enslaved species and meets Lupe while being forced to gather data on Earth. He returns to his ship, where he’s attempting to inspire a nonviolent uprising using overtly Christian (though not referred to as such) principles he’s learned from the mysterious, unseen “Dawn Star”. The enslaved aliens have lithe, humanoid bodies and elegant horse-like faces. They’re basically horse people, but with wings, and dressed in tiny speedos. Almost every information-heavy page of this section took slow, careful reading, and usually re-reading, mostly because the horse aliens all look very similar, and what slight differences they have (some have spots or speckles or different haircuts) get lost or confusingly abbreviated in wide shots. In addition, the backgrounds are often pretty simple and Gregory doesn’t vary her framing much, so no matter what’s going on you’re usually seeing two similar-looking characters facing each other in profile, which gets extra confusing because she often inserts quick flashbacks or cutaways to different conversations with no authorial indication. More than once I muddled my way through a confusing sequence of panels only to realize I was reading it as one scene when it was actually two or three different sets of characters and locations. In Gregory’s defense, I don’t think I found any spots where there genuinely wasn’t enough information to parse what was happening, it just took a lot of work. And while I did, on one level, appreciate the lack of handholding–and it’s true that she mostly followed the letter of the law re: clarity–the book has the feeling of a private conversation: a bit rambling, a bit involuted. It feels like what you might write if you lived alone on a desert island. She’s got so much affection for the characters that she seems happy to sort of sit back and let them bicker or soliloquize for pages and pages. There’s a lot of extremely thorough interior monologue stuff, with characters just rattling off every little thought running through their heads. Not too far off from what it’s like to be an actual human being, really… but I enjoyed the effect a lot more in Gregory's Artistic Licentiousness miniseries, where it was authentically relatable, whereas in this book it’s alienating, since it all has that aforementioned “under-reaction” quality in relation to the crazy events surrounding it. Anyway… I’m harping on the negatives, but it really is a unique, idiosyncratic book. Maybe more interesting than actually enjoyable, but pretty darn interesting. And also beautiful.

Gregory includes some fan letters at the end of volume one. Howard Cruse says “As I go through your synopsis, I see many strange names and cultures that could easily be overwhelming. It’s sort of like skimming the Bible!” Which sounds about right. Trina Robbins says “it’s really hard to tell these guys apart,” and also, coincidentally, “I haven’t been this moved by a comic by a woman since I read Sharon Rudahl’s Crystal Night.” On her website, Gregory describes how she “brashly handed a copy of the first book” to Moebius, and he later tracked her down and told her he really enjoyed it and thought it was “full of ‘wisdom.’” That’s not quite how I would describe it; to me it’s full of an almost naively earnest sort of passion, though I can picture this naïveté as one prong of a horseshoe, adjacent to and almost synonymous with the “wisdom” prong…

Anyway, the first volume wraps up with about 800 loose ends. There’s a volume 2, which I also picked up, but I need a long break before I give that one a go. Worth noting here, though, that it’s much shorter, was published about 10 years after the ETA given in book one, and has artwork that looks way, WAY more rushed and simple than volume one, which is very careful and elegant, and quite beautiful in spots - especially the alien sections, which seem to bring out the best in Gregory, drawing-wise.