It had to be kismet.

No sooner had I finished reading Over Easy, Mimi Pond's new graphic novel, than I received an email from Dan Nadel asking if I would be interested in interviewing Pond for the Journal.

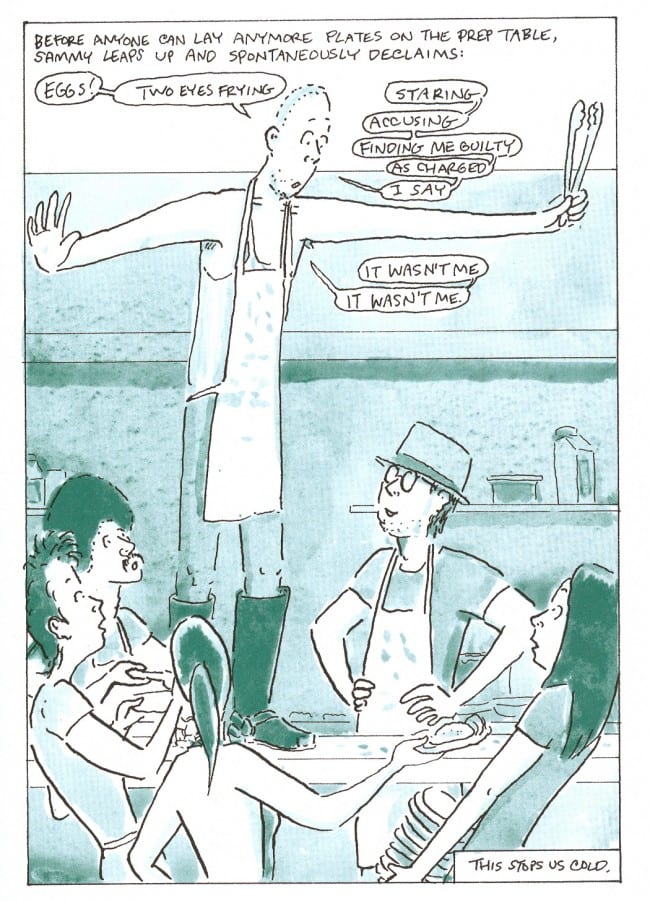

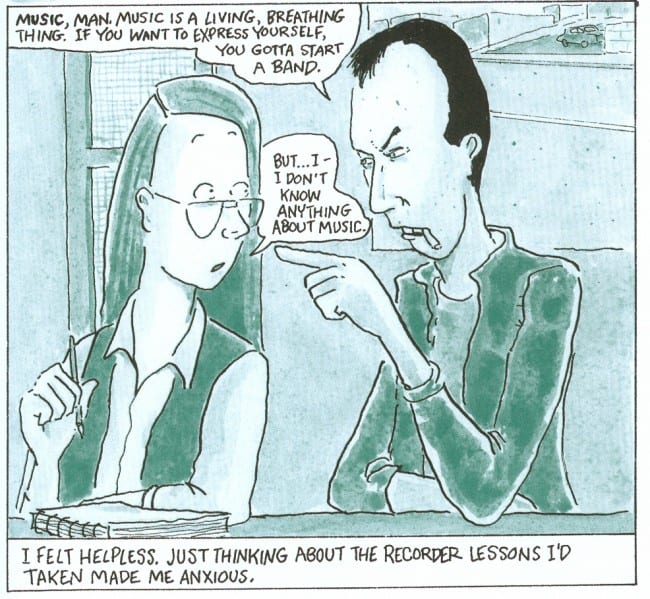

It didn't hurt that Over Easy is one of the first great books of 2014 in my estimation — a sharply observed, warm and witty comic, based on Pond's experiences waitressing at a colorful and unique Oakland diner during the mid-1970s.

Then there's the fact that Pond has had an extensive career in comics and publishing, getting her start at places like the National Lampoon and the Village Voice before publishing a series of humor books like The Valley Girls' Guide to Life and moving on to writing for television (her most celebrated credit would be penning the first episode of The Simpsons).

And then I remembered: Her husband, the celebrated artist Wayne White, was in nearby York, working an installation involving giant Confederate soldiers made out of cardboard. Perhaps Pond had accompanied him on this trip?

She had. Obviously the fates were aligned in my favor, so I made the 30-minute trip to the Marketview Arts Gallery to talk to Pond about her new book, its long gestation period, her career as a cartoonist, and her wild and wooly experiences in Hollywood.

Chris Mautner: What’s your impression of central Pennsylvania been so far?

Mimi Pond: York is just fascinating. In fact, Peggy [Burns, Drawn and Quarterly’s associate publisher] got me this gig doing a culture diary for The Paris Review. I’m doing it while I’m in York. I’m from San Diego, where everything in Southern California that’s older than 1967 they tear down and rebuild with Popsicle sticks and Elmer’s glue. So the thought of all this history and age is fascinating.

My first impression of York is that it was like one of those mini-metropolises that Seth does. It fills you with this yearning and sadness for what these places once were. They were booming metropolises; they made things here, big, heavy things. And it was bustling and full steam ahead, and now it’s a shell of its former self. They’re trying really hard to bring [the city] back but it’s [full of] empty streets. You want it to be able to work for them, but there are so many empty storefronts.

It’s an issue that a lot of the cities around here have been having. Let me know if you need any tourist spot recommendations.

We’re really just working nonstop here. Wayne is working around the clock on this thing and I’ve got my nose to the grindstone, so we’re not really going too far afield. We do have a car but mostly we spend our days walking to and from the hotel.

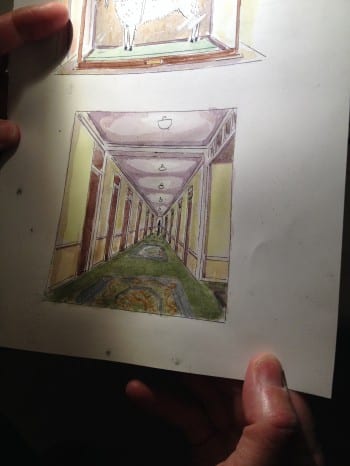

The hotel in York is very much a Seth kind of place, full of the ghosts of old businessmen. In the lobby there’s this stuffed goat that was the mascot for the fundraising effort to build the hotel in the first place in 1926. The hallways are just spooky. There’s this old haberdasher that sells ghetto fabulous clothes.

When Peggy suggested [the Paris Review diary] I had just finished doing all this huge pile of tone work. I was feeling like I wanted to draw it all like Seth does. So I assigned myself to do this giant pile of drawings for this diary. You get stuff from the 1700s and this mid-Victorian that makes these buildings look like these mini-Smithsonians. Then you get art deco. The thing that kills me most is this outsize sense of scale. I don’t know if you’ve ever been in this building, the York Water Company. It was built in 1929. The woman who [gave me a tour] is a local businesswoman whose husband is the president and CEO of the company. That’s the great thing about small towns; everybody knows everyone.

This building is just ridiculous. I took photos. The lobby by itself is the size of my house. It’s just immense. It’s one of the oldest private utilities in the country. It’s been providing water since 1814. It has paid dividends without interruption even through the Confederate occupation of York. [Showing photo] Look at that! You walk in to pay your water bill and this is what you get! Everywhere else in the country, the water company is in a strip mall. This is informing the citizenry that this is a grand place. All these murals are done with a theme of water. Upstairs in the board room, they had these portraits of the boar members. They’re really bad. (laughs) And then there’s the courthouse, the one on Market Street. It’s fucking huge! You look up at it and think, “If you’re on trial for something you’re in trouble.” It’s this outsize sense of scale for utilities and law and money. This building here on Market Street looks like Scrooge McDuck’s money bin. It’s ridiculous.

I’ve traveled across the country and been through cities that once were little mini-metropolises and now they’re just ghost towns. It also makes me think of Bruce McCall, this ridiculous outsize scale. You think of the authority and weight that this architecture had over people.

I got the feeling from reading Over Easy that this is a book that was a long time coming and had a long gestation. Am I correct in that assumption?

Yeah. 35 years.

The first day I went to work [at the diner] I knew it was a story. I knew this was some kind of big story that I was going to have to tell. At some point I was going to have to figure out what the story was and I was going to have to tell it. I just knew. It took me years. It was always in the back of my mind, “I gotta do that.” You know how it is when you’re driving and you almost get into an accident and you think, “Oh, I gotta do that book before I die.”

Can you walk me through the gestation period? Why did it take so long for it to come out?

After I left the restaurant I moved to New York and became a cartoonist and was making a good living doing that. At that point no one was talking about graphic novels. I always thought it should be a movie. I thought about doing it as a screenplay.

We moved to L.A. and I lived there long enough that I realized just how horrible Hollywood is and even if I did write it as a screenplay it could be taken away from me at any time and ruined. And I wanted to make sure that it got told the right way. So then I thought, “Graphic novel? That’s way too much work. I could never do that. That’s ridiculous.” I thought, “I’ll just do it as a regular fictionalized memoir.”

I fictionalized it because there was just too much stuff in real life; there were too many people who passed through there, too many personalities. It had to be winnowed down into a dramatic story. I wanted to catch the essence of what that time and place was and who those people were, but I didn’t want to have to stick to the facts.

It wasn’t until my son was born in 1992 and suddenly being a mother for the first time that a light bulb went off in my head that Lazlo, the real-life version of him, was everyone’s groovy beatnik dad. He had his own family. And yet he was hanging out with a bunch of twenty-something kids instead of spending time with his family. And I was like, “That’s not right.” (laughter) In his own way he was as good a father as he could be but l feel like he failed to protect his family. He put them through things … I don’t want to get into it in the [book] because I didn’t want to get that personal, his wife and kids are still around, and I didn’t want to make it about that as much as I wanted to focus on the restaurant.

When you’re in your twenties, it doesn’t occur to you to think about things like someone’s responsibilities and parenthood. You’re not thinking that way. I realized this character is much more complex than I had even thought. In some ways he was a wonderful person and an extremely important person for me because he was telling me and anyone else who was there that while this is what we’re doing right now, we’re just playing a part, and we’re going to do other things and we have to keep notes, because this is a story and it has to be told. Working in a restaurant is just a role we’re cast in the moment, but we’re going to go on and do bigger things.

When did you officially decide to start making it a graphic novel?

It was just in fits and starts. My agent couldn’t sell the manuscript.

Why not?

He was someone who had been my editor. He had been on the editorial side for a long time. He had been in publishing for years and years, and he decided to go “agenting.” I don’t know, mainstream publishing just sucks [Mautner laughs]. It does. Someone had the temerity to suggest that I should do it as a graphic novel and I got really mad about it. “If I wanted to do it as a graphic novel I’d do it as a graphic novel. The nerve!”

He couldn’t sell it and finally I was like, “This is really who I am and this is really what it wants to be.” Art Spiegleman is an old friend and I spoke to him about it and he was just like, “Well you should just do it [as a comic].” When Art Spiegelman says that, you should just do it [laughs]. I guess it about 2006 or 2005. I don’t remember exactly in the blur of motherhood. I started writing it around 1998. I did about 30 pages and then showed them to [my agent], and then my agent still couldn’t sell it!

What were you hearing from people? Were they not giving you a reason for rejection or were they saying it’s just another memoir or …

No, he would send it out and just get back a “no.” Then I became friends online with Vanessa Davis, whose work I really liked, and she said, “Well you should show it to Tom Devlin.” I think that was 2009. I went to meet him at Comic-Con and showed it to him and he liked it. They wanted to see 20 more pages so I went back home and cranked out more and eventually they said, “OK, we want to buy it.” And then they said, “From here on out we want you to separate the line from the tone.” Which is just excruciating.

In layman’s terms …

They wanted to shoot the line work separately from the green tones, because it prints better. It’s just twice as much work.

'Cause you’re doing the page twice.

Yeah. And on top of that I can’t really show it to anyone 'cause I can’t expect anyone to peer at it on a light box and read the line pages that have all the writing on them and try to imagine what it really looks like. Plus, it’s just guesswork, like, “I guess this will work” [laughs]. 'Cause I [didn’t do it] on a computer. That would have taken even more time and money to buy the necessary equipment and then there’s the learning curve. I was like, “I just need to get going on this.”

The thing that was frustrating is that I’ve been working all this time on it and incapable of really showing it to anyone outside of my immediate family to get any feedback. It’s been like working under a rock.

Do you feel like you’re starting to get feedback now?

Finally. Just now.

How’s the reaction been?

It’s been great, which is a tremendous relief.

Take me through your working process. You had the story but I imagine you had to rework it for the comic.

Not so terribly much. I had gone through the manuscript and it’s like 130 pages or so, maybe it’s 230 pages. [Looks through pages] Let’s say 270 pages. So I’d go through it and make notes like, “Draw this instead of describing it.” It’s “show don’t tell.” There were a few characters that got booted out, a few side stories I decided was unnecessary and had gotten in the way of the action.

Every sentence cries out to be a page. I can see it all in my mind. I’ve got it all in there. It’s a matter of, “This could be a panel and this sentence could be three panels.” Occasionally there’s a sentence that’s warrants a full page but I just wanted to do it justice. I didn’t want to leave anything out that I felt was important. It’s just a good thing I like to draw [laughs].

Did you sketch page roughs beforehand?

Yeah. [Gestures to a corner of her workspace] There’s part two that I’m working on right now. That’s a sentence that got to be a full page. And then I’d go back and do the line work. I do it chapter by chapter, complete a chapter at a time and then do the next one. And while I’m still doing a rough I lay it out at a certain point and see how the flow is going from page to page in terms of not repeating too many busy pages. You want to break for something big in the middle. It has to have its own rhythm and breathe.

I wanted to ask you about the pacing. It does feel like the book has a steady rhythm, especially when you detail your first day on the job. How conscious were you of maintaining that?

It’s nothing that I intellectualized or thought of consciously. It’s just visual decisions. I think all that kind of pacing really happened when I initially wrote the manuscript. 'Cause with writing you’re constantly editing yourself down and trying to cut it down to the bone so that it’s not flabby, even more so with making comics pages. I see a lot of graphic novels that have a lot of pages without writing on them, it’s all visual. That’s not necessarily the best thing, because it’s like, how many times do you want to see this from how many different angles and what’s the point? I admire those stories that are told just visually, but I love words and I love reading and writing and I don’t see why you can’t combine all of it.

What was the biggest challenge for you? Was it making the separate tones? Was it something technical?

It just took awhile to get into the rhythm of doing that much drawing for that long a period of time. The thing is that I’ve been working on this for five years on and off, since I really got going with Drawn and Quarterly. Finding the time to work uninterrupted was a real challenge, cause my kids were home – my son is actually graduating from California College of the Arts, which is where I went to art school in Oakland. It used to be California College of Arts and Crafts and they changed the name, which is stupid.

He’s graduating in May and our daughter just started at Cooper Union, so we finally just got both kids out of the house, which is great. This is what’s great about going away from home to work: There’s nothing to do but work. There’s no interruptions, no phone calls to make, no forms to fill out, no errands to run. It’s just the best way I know to get work done.

Up until the last couple of years it’s been fits and starts. Just really difficult cause you couldn’t get any traction. I’d be working and have to stop. At home there’s always this period of dicking around before I get down to work. I’ve got to fidget and fidget and fidget and sometimes it’s like three days of tortuous fidgeting at my desk before I finally get down to it and then I have to stop because I have to do this thing that’s going to take me days to do and then I have to start all over. It’s ridiculous.

So that alone, not having uninterrupted time to work was difficult. And then just getting used to the rhythm of doing that much drawing. I finally got used to drawing panel after panel and imagining, “What does the restaurant look like from this angle?” I’ve got tons of photographs but there’s always some point at which you realize you don’t have it from the angle you need and you’re just going to have to make it up.

From the technical aspect there are far more proficient artists working out there than me who crank stuff out all the time. It’s daunting and impressive, but for me personally it’s teaching myself how to do all that stuff and make it work and actually drawing street scenes of Oakland. The biggest tool that I had was Google Earth. It’s the greatest. Oakland hasn’t changed that much. What does 40th and Broadway look like from this angle? What about from that angle? [Mautner laughs] it’s just so useful.

This is the longest book you’ve ever done. Was that daunting?

It was daunting initially. I finally committed to doing it. They said, “When do you think you’re going to have it finished?” and I’d be speechless. “Let’s see, next week I have to do that thing and … I don’t know?”

One of the things I liked about the book is that it’s set in this very specific time and place with the peace and love movement gone, punk rock is just starting up, but you’re right in the middle with this feeling that your generation has missed something.

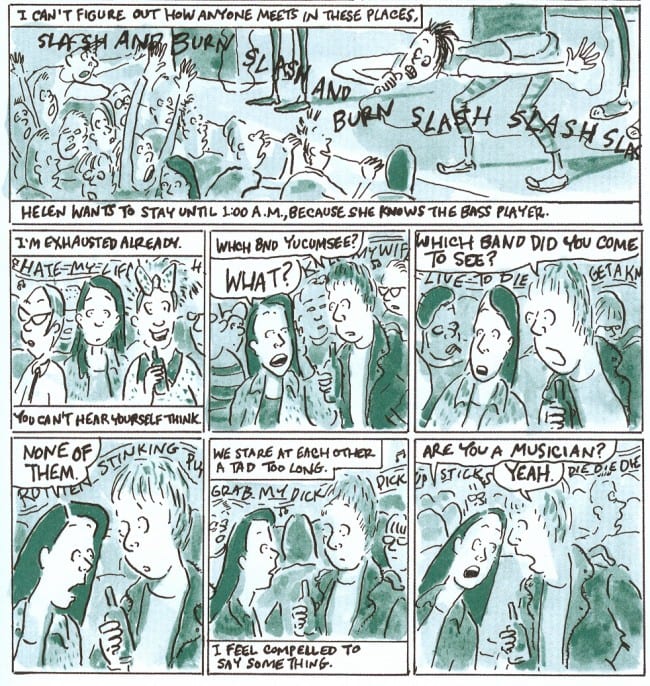

Yeah, actually that was maybe the most exciting time for all the punk stuff because it was brand new and hadn’t been co-opted by the establishment. It was just raw. I have never been a club person, I just can’t stay up late. I went to Mabuhay a few times, I went to the Berkley Square. But I had to get up and work. I’m not good at staying up all night and standing around in hot, smoky clubs. I was the person who was waiting on those people who would come in at noon or 1 p.m. after sleeping it off.

But the raw energy of the do-it-yourself aspect of punk, and the way people were dressing, like thrift store clothes that they modified to make it seem brand new and strange, was one of the most exciting things for me.

I think to modern eyes the characters are people we would look at as engaging in self-destructive behaviors with sexual relationships and casual drug use. You take an effort to not be judgmental. There’s a sense of foreboding, of things going on behind the scenes that make them act out, but at the same time it’s just part of the scene.

Yeah, well, the second book gets more into the drug thing, 'cause it was really fun until one day when it wasn’t anymore.

I wasn’t really into the drugs cause I knew I had to go on and move to New York and make this book eventually. Plus I guess I’m too much of a product of my Depression-era parents’ tightwaddery. A bindle of coke costs me 30 bucks? That’s my tips for the day! That’s just stupid! I’m going to be high for 15 minutes and then I’m going to feel stupid! So that never really had an appeal for me.

As far as the sex part, I’m really, really tired of this current attitude of slut-shaming women for being sexually promiscuous when men continue to have sex randomly and nobody ever says anything about it. Back then the great thing about it being the sexual revolution was that no one was passing judgment because it wasn’t a big deal. It was like, “Everyone’s doing it.” It wasn’t like you were doing it because you had low self-esteem and were slutty or anything. You were just doing it because you were bored and it was something to do and it was easier than having a conversation.

It seems like we live in a more judgmental era now.

Yeah. The only thing I didn’t do was sleep with my co-workers because I liked the job too much. I didn’t have a whole lot of sense but I at least had that much sense [laughs].

The book seems like a paean to hard work and discipline.

Yeah, I guess. That’s interesting.

In the way you go through the duties of the job and the way people treat their work, there’s a sense that the people there do treat their work seriously because they recognize it’s a special place.

Yeah.

But there’s also the idea of it being a training ground for you, not just as an artist but as a twenty-something coming into adulthood.

Absolutely. That’s the great thing about working there. Everyone was serious about the job. There were a few people who were slackers but everyone wanted to be there. There was no more fun place to work. I don’t think I could have worked in any other restaurant ever after having worked there, because there’s no way it would be anything like what [I experienced]. This character Lazlo was casting his own opera every time he hired someone: “Tell me a joke or a dream.”

You mentioned how you had to kick some characters to the curb. I imagine some are based directly on specific people but others are amalgamations?

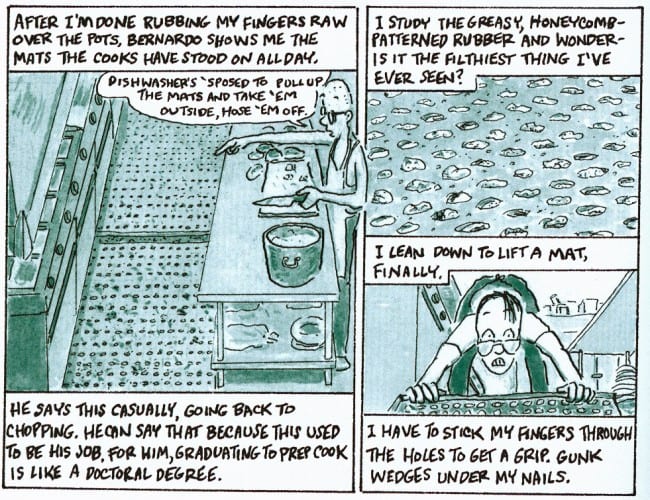

Yes. And there were so many people that came through the place … and there were some whose personalities were just too large to fit to be tertiary characters. I had to focus on the main characters and what they did and what they brought to the story. The cook Bernardo is a complete amalgamation—and so is Sammy—of a number of different cooks who worked there. And then even some of the characters that were based on real people I had to wedge some aspects of a few other people into them to compress both characters and action.

I wanted to ask you about your color choices. Why specifically green?

Well the restaurant itself is still there, it’s Mama’s Royal Café. [Pulling up her laptop] I can show you pictures …

Is that the cook?

Yeah, Tony. He’s pretty verbatim. “You lying whore.” It had been a Chinese restaurant and this beautiful place with these cute pagodas. [pointing to photo] That’s really “Rye Toast Peg,” the retired manicurist who hangs out in the bar all the time. And that’s the guy who called me “personality plus.”

I was really inspired by Fun Home, cause she had done so much with just that shade of blue, and I was aware that whoever was going to publish this, if I did it in full color it would cost a fortune. Just doing it in color would be kind of exhausting because as much work as doing it with one color is, making all those color choices, page after page [would be] just too much. Way too much. I really like that shade of green. It’s not specifically the same color as the restaurant.

And actually Fun Home, that came out in 2005 and I guess that was what made me seriously start thinking about doing [the book]. Because it was like I finally found a [graphic novel] that told a story in a way that I could relate to. The thing I love so much about that book is that it’s just as compelling as any regular written piece of fiction, but with pictures. Decidedly an adult kind of story and not another one of those graphic novels that straddles … it just seems like there’s a lot of stuff that could be for kids, could be for adults, and this is a serious adult examination of a life. It was the first time I had seen a book that made me think, “That’s the way I want to tell a story.” Sort of a model or template I guess.

Were there other influences?

Not really. I haven’t paid that much attention [to comics]. The whole graphic novel market has just exploded to the point where it’s impossible to keep track of everything. And it gets expensive too. If I was ever a person who hung out in bookstores, I haven’t been since I had kids. You don’t have the time to do that. I really love Miriam Katin and I like women’s stories. I love Maus, but it’s so much easier for me to relate when it’s a story told from a woman’s point of view and there just aren’t that many graphic novels that are specifically that.

You became a professional cartoonist at a time when there weren’t almost any professional female cartoonists. Was that difficult when you started out? It’s tough enough to be a cartoonist.

My dad was an amateur cartoonist who taught me how to draw cartoons originally. No one ever said to me I couldn’t do it. And as I got older I looked around and realized there weren’t that many women cartoonists. I knew there was Brenda Starr. I didn’t even know that Little Lulu was done by a woman. I thought, “Marge? The guy’s name is Marge?” [laughs] It was really hard to find out about women cartoonists back then. There was nothing to go on. But then National Lampoon came along while I was still in high school. MK Brown was a big influence and Shary Flenniken. Sherry wound up becoming my mentor. She’s the one that first bought my cartoons and let me stay at her apartment.

What year was that?

I think it was 1981. When did Doug Kenney die? Because when I got to visit Sherry for the first time after meeting her – I had sent my work off to a bunch of magazines in New York and she had miraculously said she wanted to buy some. She said she was going to be at Comic-Con, which I had been going to since I was about 14. I went to one of the first ones. It was still being held at UC San Diego. I got to meet Ray Bradbury, which was exciting.

So she said she was going to be at Comic-Con with MK Brown and Sam Gross and some other people, so I drove down to San Diego and met them there and hung out with them. And then she sai,d “You should move out to New York. You can stay with me.” I was like, “Yes, now we’re talking.” I show up to her apartment, she says, “We’re going to Connecticut to Doug Kenney’s funeral.” I’m like, “What?” I had no sooner set foot in her door than I find myself at Doug Kenney’s funeral in Connecticut, which was really strange.

I went to visit her another time and then made one more trip and stayed with someone else and was meeting other cartoonists and going to the New Yorker cartoonist luncheons on Tuesday or Wednesday, whenever they had them. I eventually met an illustrator named Roxie Munro, who was doing covers for The New Yorker, who was giving up a sublet at 113th on Broadway. So I took it over. That was January of 1982.

Actually I would say at that point being under Shary’s wing, being a woman in cartooning was not that hard. If anything, it was like being in an all-girl jazz band in the 1930s. It was a novelty. People were interested in you because they never heard of a woman cartoonist before. It was like a novelty act.

What was it like having her as a mentor?

What was it like having her as a mentor?

She was great. She really taught me a lot about cartooning and introduced me to a lot of people and really changed my life. I can’t thank her enough.

Then I found myself living in New York and getting down to my last $400. I started doing full-page cartoons for The Village Voice with Mary Peacock, who did the style page called the V-Page. She’d just give me the whole page and it was really wonderful. The Lampoon was great but a lot of the readership by that point – this was after the heyday with Michael O’Donoghue and P.J. O’Rourke. It was going down but not as far down as it eventually would go. But a lot of the readership was 14-year-old boys and prison inmates. [laughter]

And so having stuff in the Voice was huge exposure and I had lunch with an editor from Dell Books named Gary Luke. I was entertaining him with my stories of growing up in San Diego and what it was like to go to high school with ten guys who were just like Spicoli from Fast Times at Ridgemont High. And doing my surfer dude accent for him: “We’re going to take some reds and go to the beach and just hang out man, it’s going to be awesome.”

So the next thing I know he calls me and says do you want to do a Valley Girl book? I hadn’t even heard the song yet. And I had to go buy the record. I didn’t even have a record player. I had to go find someone with a record player, listen to the song and then go, “Oh, yeah, it’s the same thing. Yeah, sure I can do that.” I went back to L.A. I spent a week hanging around L.A. and going to the Sherman Oaks Galleria and talking to teenage girls, taking notes, and wrote this Valley Girl book in six weeks. And then it was a bestseller, thank god, so I had some money again.

That must have been very encouraging.

Oh yeah. It hasn’t happened since, but it was really fun. And then I got on the ‘80s humor book gravy train for a while. It just seemed like for a while you could write a book proposal about anything and they’d buy it. It was amazing.

I know you did one on shoes, and another one –

Secrets of the Powder Room, which is about relationships, at which point I knew absolutely nothing, I realize now. I just had a lot of bad boyfriends [laughs], which is different than knowing what relationships are really about. So it should have been called The Bad Boyfriend Book.

You came at a time when the Lampoon hadn’t slid yet and the rise of the alt-weekly and a lot of cartoonists coming to the fore.

Yeah, magazines were publishing a lot of comics back then.

Did you get a sense of being part of a club or scene?

Oh yeah, there was definitely a scene. We thought it would never end. [laughter] And then I moved to L.A. in 1990 and I woke up one day and my career was gone.

Was it really that quick?

No, it was gradual. I did a comics page for Seventeen magazine for – I don’t know – five years or something and then they pulled the plug on it. I wasn’t getting as much work because I was in L.A. and everything was in New York. But then I had my son in 1992, I was still doing stuff, I think I did stuff for Seventeen until he was about two or three. I’d get odd jobs here and there and then it just trickled down to nothing. Suddenly I couldn’t get arrested.

I thought for the longest time it was because I moved to L.A. I actually gave myself a self-imposed residency for a month in New York two summers ago. I just put out the word that I needed to go away and work somewhere, and a couple friends in New York volunteered their apartments for apartment-sitting. I had been back to New York a number of times, but I hadn’t been there on my own and got to catch up with a lot of old friends, but it wasn’t just me. People who had stayed there all this time have had a really hard time because the market has changed so much.

Is that how you edged into writing for television?

Well I came to L.A. thinking, “Oh, I’ll just turn myself into a TV writer.” I had already done cartooning and illustration and I thought, “The big money’s in television! Let’s do that!” The thing that ruined me for writing for television is that I wrote an episode of Pee-wee’s Playhouse with Lynne Stewart who played Miss Yvonne, because my husband worked on the show as a production designer. The problem was that we wrote this episode and then they shot it. [laughs] They just took our script and they shot it.

And you thought that happens all the time. [laughter]

All the time! And I was so disappointed to learn that in every other instance, they take your script and ten people piss on it [Mautner laughs] and then they shoot it. That’s the way it works, and I’ve never really been a group person. My sixth grade teacher wrote on my report card, “She doesn’t interact well with her peer group.” I just am not good at that.

When my son was six months old I worked on the last season of Designing Women and Linda Bloodworth was off winning the election for Bill Clinton and the inmates were running the asylum. They were making all kinds of decisions about what to do with the characters that were I thought kind of stupid. Nobody wanted to be there anymore and I wasn’t getting any sleep because I had a six-month-old and I had never worked in an office and I had never worked on a TV show before. I didn’t know what the hell I was doing and nobody there knew what they were doing. It was just a nightmare.

Then after that my husband and I pitched – because we both had some credentials. He had all these credentials working in children’s television and I had done the Simpsons episode and I had done Pee-wee – so we’d go pitch ideas for shows and until we were blue in the face.

One day there was this one guy we were working with who kept getting us to do all this work on spec for no money and he had us going around and around and he had come back from a meeting with Nickelodeon or something and they hadn’t bought our idea but now he had this new idea he wanted to tell me about and if only we could just – and he was yammering on and on and it was getting towards dinnertime and my kids were six and three, and I was sitting listening to him and I finally said, “I’m sorry, I just can’t listen to you anymore.” [laughter] And he stopped and said, “Oh. Ok. Well then, good-bye.” And everything came to a crashing halt.

One day there was this one guy we were working with who kept getting us to do all this work on spec for no money and he had us going around and around and he had come back from a meeting with Nickelodeon or something and they hadn’t bought our idea but now he had this new idea he wanted to tell me about and if only we could just – and he was yammering on and on and it was getting towards dinnertime and my kids were six and three, and I was sitting listening to him and I finally said, “I’m sorry, I just can’t listen to you anymore.” [laughter] And he stopped and said, “Oh. Ok. Well then, good-bye.” And everything came to a crashing halt.

I don’t remember if that was the dramatic, very last straw that broke the camel’s back. I got paid really well to be the first of what turned out to be six writers on a feature for Disney that never got made. [They] must have spent millions and millions of dollars.

What was it called?

“Wild Life” I think. It was a really good idea. It was just too good an idea for Disney. It was too original. It’s about a elephant who lives in a trailer park in Florida with a bunch of other animals. The villain was based on Andy Warhol as an evil impresario who comes from New York to do a photo shoot in this trashy trailer park and his rail-thin model friend who’s his muse is taunting him and he says, “I can make anyone a star,” and she points to the elephant and says, “Make her a star.” Then of course it’s revealed the elephant has this beautiful singing voice and he brings the elephant to New York, she becomes a big disco star and almost loses her soul.

That sounds great.

I was having a really great time writing that and getting paid well for that, until they didn’t like it and kicked me off the job and gave it to five other people.

Before pulling the plug on it.

That was about 1997 or ’98. It must have been after that I thought, “If I’m not making any money anyway I might as well get this book down.”

Can you tell me a little bit about working on The Simpsons? Was that a positive experience?

No, it wasn’t. And I don’t … Matt [Groening] is a friend and was a friend and what I didn’t know and what no one told me was that he was already having trouble with the writer-producers and when he brought me in I was just someone from his camp who they didn’t like. On top of that I was a woman and it was a boys’ club and no one told me that either.

I didn’t get invited to be on staff and no one explained why and it took years of finding out through the grapevine that it was a boys’ club situation. So I feel like I got thrown off the moving gravy train.

On top of that, even though it’s my show, it’s the first show and I obviously have credit for doing it, a couple of those people have said things like, “We totally rewrote it, she didn’t really write it.” Which is bullshit. Every show that everyone ever writes gets rewritten. Of course it gets rewritten by other people. But for them to just undermine the only credit I have by saying … I have struggled with this. I know this book is going to come out and people are going to ask me about this, and nobody wants to hear anything negative about The Simpsons. And I’m here to tell you –

I totally want to hear negative things about The Simpsons.

It was for a very long time a boys’ club and … it was just not a positive experience.

Sorry to open that wound.

“It must have been really fun!” I have to rip [people who say that] down. No, in fact it wasn’t. And yet at the same time if I had gotten on staff there my life would have taken on a completely different direction. I would have been making so much money that I would have felt compelled even after having children to hand them off to nannies the way people do. I really never wanted to do that, which is why I never really got that into wanting to pursue writing for television any more than I did. I just hated being away from my kids. I’m really grateful I got to be home with my kids when they were little.

I wanted to ask you about that because your press release mentions how you had to put your career on hold. You talk in the documentary about your husband [Beauty Is Embarrassing] about having to put your career to the side. Was that a specific, conscious decision? Because you’re talking about markets changing and being frustrated with Hollywood.

I didn’t want to work in television that badly. If I really wanted to I would have pursued it more. But it was shaping up to be something I thought I wanted and really didn’t as much as I wanted to experience seeing my kids grow up. It was partly conscious and it was partly just the way it went. The jobs weren’t throwing themselves in my path and I wasn’t actively, aggressively pursing them either. Luckily my husband was making enough money working in doing production design and TV when the kids were little that I didn’t have to go out and find anything.

There’s a part in the documentary where you talk about feeling invisible, and my wife who was watching with me pointed at the TV and said, “Exactly.”

Yeah! A great job for women with small children would be to be private detectives. You could go stake someone out pushing a stroller and no one would ever know you were there! They would look right through you.

It’s kind of horrible. And when you do socialize people assume all you want to talk about is your kids when you’re like, “No, I had three hours today when I got some writing done and it was really great.”

Are you frustrated with that time lost?

That was the way it was. Being with my kids was great. Having to socialize with parents of my children’s friends was the most painful part. People you normally would cross the street to avoid you have to hang out at events with them. [Mautner laughs] Oh god! It’s horrible. That’s what I’m most bitter about, is the time wasted having to chat with people I hate.

At recitals or soccer games or whatnot.

Oh man, there’s a couple of real standouts in the sheer asshole department.

Getting back to the book, what do you take away from this era you portray? Not so much your waitressing job but the time and place of that particular mid-'70s period. Is there something that can be absorbed or readers can learn from?

Well there was a sense of being unmoored, which is not the worst thing that could happen to you. I think there’s a danger in staying on the straight and narrow and going to college, and getting a serious job right out of school. I think that’s a lot of reasons why TV is so bad, because they hire kids straight out of Harvard to work on comedies and they don’t have any life experience to base it on and so everything is a pop culture reference instead of a personal life experience reference, something really weird that happened to you, something that could only happen to you if you were in a shit hole job working with some crackpot, the juicy stuff of life. Sometimes you want to shake someone and say, “Didn’t you ever want to wake up in the back seat of a car and not know where you’re going?” You know? I mean, weird shit happens!

You said you’re working on a sequel. Tell me a little bit about that.

It’s just a continuation. It would have been all one volume, but they didn’t want to make a book that thick. So it’s just a continuation of the story. I don’t want to give it away.

What will the title be?

I think it will just be Over Easy: Part Two.

Will it be the same length approximately?

I think about the same length.

When will it be out?

I don’t know if I’ll be able to finish it by the end of this year or not. I hope so.

There was a time in the comics industry where, if I didn’t read everything, I could be aware of almost everything that was out there.

There was Gary Panter and Kaz and Newgarden, Charles Burns and Dan Clowes and Crumb and a few other people, of course Raw, everyone who was in Raw, Spiegelman and all that stuff. And now it’s this explosion and you can’t keep track of it all.

What’s your impression of the industry, coming back into it now?

I haven’t really experienced it from the inside. I haven’t been to Comic-Con in a few years. It’s funny. At Comic-Con it’s been so completely corporatized by movie and TV studios and the major mainstream superhero comics stuff, that the whole independent publisher part of it is just a tiny ghetto in that thing. It’s a drop in the ocean compared to all that other stuff. I know that there are people who are into comics who are into everything, but I hate superhero comics. There was never anything there for me. There was not the least bit for a girl in that stuff. The classic superhero stuff, I have a full appreciation for the aesthetics of it, it’s beautifully done. The new stuff with the airbrushed color? Ew. Yech. Uck. Even of the stuff that independent small press publishers do, there’s only some that I’m interested in.

Are you surprised by the breadth of it? Are you surprised there are so many people making comics?

Yeah, I just wonder how long it’s going to last. Having seen that whole fad of humor books in the ‘80s come and go, I wonder how long it’s going to be before they figure out how much money there really is in it. I wonder how much money there really is in it.

I went to the Small Press Expo last year. It was enormous. And I saw all these cartoonists, and thought how big an audience can justify this? I feel like there are more comics being made and more interesting comics being made than ever before, but worry that these people will not be able to make a sustaining career of it.

I’m just extremely lucky to have my career subsidized by my husband. That’s the only way I can sit home and do this, is that someone else is making the money and paying the bills. You can be young and starving and doing it for a little while. I don’t know how long people can sustain that. There are a few people that can hit the jackpot with Hollywood, which perceives it as storyboards, which hopefully will be the case with my book, knock wood. There’s so much interest in the ‘70s [adapting the book] seems to be an obvious choice. That microcosm experience when the characters are compelling so, “Hello, Hollywood!”

Do you have any interest in collecting your earlier work?

If someone wanted to do a collection, that would be great. I’ve done a bunch of stuff for the L.A. Times too.

There’s a strip you did about you and Vanessa Davis going to –

Oh, the hamster thing.

That was wonderful. That was a great strip.

It’s the kind of thing where I had already been working on this book, for a while and we had this experience and I was like, “Whoa.” It was months before I sat down and did this story because it was so compelling. I haven’t ever done webcomics like that before. I know people do it all the time, I’ve got this massive life project book to do and never had the time or energy to do it and I’m so old school about my work that the thought of putting out a comic strip without a deadline or a pay check – “What? You’re fucking with my brain!” [laughter]

You’re married to a relatively famous, successful artist. Has that proved a challenge? Looking in from the outside, it would seem like having two creative people in a marriage could create tension.

At times it’s difficult. It was really bad when in 2012 he was promoting Beauty Is Embarrassing. He went to like 26 cities. It was crazy. He was gone a lot. Our daughter was in her junior and then senior year in high school. Somebody had to be home to hold down the fort. He was in this weird celebrity bubble at the time and I was at home doing all the grunt work. That was a hard year.

Since our kids are now more self-sustaining, I have a lot more time to myself. The thing is the situation has always been: he’s the one making the money so I’m the one who picks up the slack at home. I have to contribute something. I have to earn my keep and I’m a responsible mother and the job’s gotta be done and you just do it. But it does get really frustrating.

I apologize if I’m being too personal. Any marriage is going to have some sort of resentment. And when you have people working in the same field that can be compounded by competition. And I was curious how you both have been able to find success in your relationship.

It’s sometimes an issue. We’ve been together for 30 years and he’s always been very supportive of me and vice versa. The great thing about living with another artist is you pick up on a certain creative energy. We work basically in the same room at home and if he’s busy working then I think well I’ve got to get to work. And if he’s having a slump and just laying around, it’s harder for me to get going too. You feed off each other’s creative energy, which is great.

We’re not doing exactly the same thing, although he started out in comics. And he’s my biggest cheerleader. He’s also my best editor. That’s really valuable to have around. It’s a mutual admiration society. I think he’s a freaking genius. And he responds in kind.