George O'Connor has been drawing comics for children and young adults in the bookstore market for nearly 20 years - which is to say his work spans nearly the entire 21st century evolution of this popular area in comics. He debuted with the superhero-themed children's picture book Kapow! in 2004, and his 2006 graphic novel Journey Into Mohawk Country, adapted from a 17th century text by Harmen Meyndertsz van den Bogaert, was part of the debut year of First Second Books, alongside Gene Luen Yang's American Born Chinese and works by Eddie Campbell, Lewis Trondheim, and the Malaysian cartoon luminary Lat. And while O'Connor has worked in several modes over the years—he has illustrated more than 20 installments of the children's book series Captain Awesome with writer Stan Kirby since 2012, and collaborated with the Pulitzer finalist playwright Adam Rapp on an older-readers graphic novel, 2009's Ball Peen Hammer—his most prominent solo work is Olympians, a sprawling 12-volume collection of comics drawn from Greek mythology, which First Second has been publishing annually since 2010. The final installment, Dionysos: The New God, was released earlier this year, and the mytho-superheroic allusion in the book's subtitle speaks to O'Connor's longstanding affection for an earlier era of 'mainstream' comics.

In the following interview, Gina Gagliano—herself a veteran of 21st century bookstore comics for young audiences, on the ground floor with the burgeoning First Second—discusses Olympians with the artist. The interview was conducted via email, and has been edited for concision.

-The Editors

* * *

GINA GAGLIANO: Let’s talk about in the beginning - what first got you interested in Greek mythology?

GEORGE O'CONNOR: I grew up in the '80s, and I think the ingredients to prime a monster-loving young kid like me to become obsessed with Greek mythology were everywhere in pop culture. My favorite toy line was Masters of the Universe, I watched the Dungeons & Dragons cartoon on tv, and one of the first movies I can remember seeing in theaters was the original Clash of the Titans. Monsters and swordplay and weird talking statues and then that scene where Andromeda walks out of the bath naked - it was a lot for my seven-year-old self to take in, and I felt like I had gotten away with seeing something I shouldn’t have (and which, arguably, might have been true).

Then, in elementary school I was part of a prototype educational program called STEPS - it was an acronym for something, though I don’t know what anymore. But we did a lot of journaling and drawing and project-based learning - we learned about Rube Goldberg, and the Algonquin and Iroquois peoples, and most key to this story, Greek mythology. Learning about this stuff in school galvanized me. That same feeling I had upon seeing Clash of the Titans was there—people getting skinned alive, cannibalism, nudity! Do they realize what I’m reading?—but because it was in school, it gave it a legitimacy, to me. I didn’t have to hide that I was reading from these edgy, possibly forbidden books. It was educational!

What was the transition like between reading material produced for kids to reading Ovid, Homer, and more scholarly work?

My love of mythology never really ebbed or waned, so I feel like Greek mythology grew up with me. I never had a period where I didn’t love it, so I kept returning to that altar, so to speak, reading everything I could find that was age-appropriate - and as I got older, more and more became available to me. My first bible when I was a kid was D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths (still a masterpiece, IMO), then as I aged, I graduated to things like junior retellings of the Odyssey and Iliad, then to reading actual translations, then to historical analyses and research papers, and so forth and so on. I kept discovering more and more, so my knowledge and interest grew deeper and deeper. It happened so gradually that it never seemed like a leap - it was a natural progression of my learning.

You’ve read a lot of scholarly work - you say that you’ve looked at things like pot fragments to tell these stories! What’s your process for finding that scholarship-– and for transforming it to a generally accessible story?

Google has been my friend, that’s for sure. I doubt I could have gone as deep in my research as I have, if I had not attempted this in the internet age. But the thing about Greek mythology is that there is no bible—no one established, canonic set of stories—its not even like Norse mythology where there’s just a handful of sources to draw on. In Greek mythology there seems to be an almost limitless source of stories one can uncover, from different regions, at different times, and none of them agree with each other. In writing Olympians, I would try to tease out a thread that interested me, and try to follow it back as far as I could. Sometimes a specific myth would not appear frequently in the written record, something like, say, the famous story of Arachne, the weaver whom Athena cursed to turn into a spider. We know it’s a story the Greeks told because it appears on vases and other art, but for whatever reason, no Grecian version survives to us. The only written sources I was able to uncover were from later in the Roman period. It was like a kind of archaeology, tracing out these tales in what survived.

The way you tell these stories–focusing on one god for each book–isn’t the way a lot of the original stories are written; they instead focus on a particular incident. What was your process for reconstructing all the myths into a more character-focused single narrative?

Like I said, there are a lot of Greek myths out there - a lot more than I could see myself covering in comics form if I were trying to do a comprehensive retelling of them all. I decided early on that the mission statement for Olympians would therefore be to sketch a portrait of the featured goddess or god, and choose the tale or tales that would give readers an idea of that deity’s personality and role amongst the immortals and mortals alike. The idea was to serve as an introduction for someone new to Greek mythology, while simultaneously offering a different take with (hopefully) a more nuanced view or insight for the more experienced mythophile.

I also knew that 12 books would be a looong journey to take readers on, and I wanted to avoid the shrinkage in sales many long-running series experience as much as possible. Olympians is a modular series - each volume can be read in any order. This has helped me pick up new readers as the series goes on, even as the child fans of the first book are now graduating from college.

As far as my process, I just immerse myself in reading the old stories until certain aspects of the personalities of the gods become apparent. Despite what I mentioned earlier—how the Greek myths were written over many, many years in many different parts of the ancient world—I’ve noticed a strong similarity in the ways the important gods were depicted. It was often very consistent, like the mythographers were writing about the same people they all knew, and many times what I would discover was unexpected. My go-to example for this is Ares, the violent, bloodthirsty and psychopathic god of war. If the Olympian pantheon could be said to have a “bad guy”, he would be the closest to it. In my deep dive of research on him, I found myth after myth, from every corner of Greece, wherein Ares was put on trial by the other gods for some violent crime. But this crime was almost always perpetrated by Ares in defense of (or to avenge) one of his half-mortal children - Ares was a good dad, or at the very least he cared whether his half-mortal children lived or died. That gave me a sympathetic trait to hang my portrait of him on.

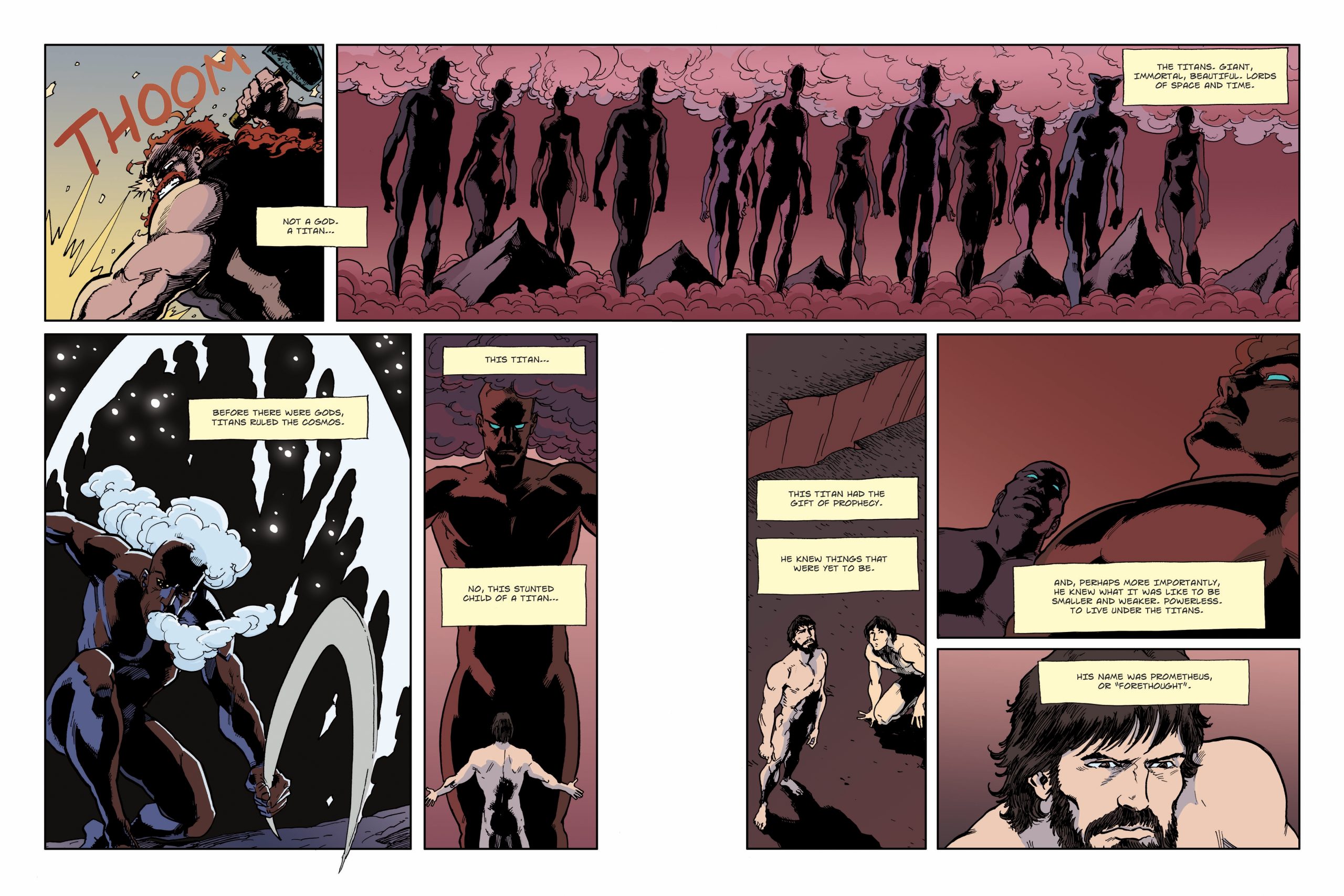

Your art style in these books owes a lot to classic superhero art. Can you talk about your influences there?

Boy, this has the potential to be a real rabbit hole. I got into comics largely because of my interest in mythology and, as a result, the comics I grew up reading, especially mid-to-late '80s Marvel comics, have been a huge influence. My interest in Greek mythology lead me to read about other mythologies, and when I was in 6th grade I was in the middle of a Norse mythology kick. That was when my mom bought me an issue of The Mighty Thor - it was during the Walt Simonson run, the issue with Fafnir the dragon on the cover (#341, I looked it up). It was pretty serendipitous for me, as a story I was just reading in my mythology books was being directly referenced in that issue of Thor. From that moment on, comics seemed to me a perfect medium to tell mythic stories in.

Walt Simonson, I think, has been a huge influence on my style - probably less his specific style of drawing and more his way of breaking down and telling a story. I’ve included a few direct homages to panels of his in Olympians. I can also see a lot of P. Craig Russell in my work, again in the way he breaks down a story, but also a bit in his figure work. Basically there is a lot of [Jim] Shooter-era Marvel in my drawing DNA. When the '90s hit, I dipped out of superhero comics for awhile, as the Image style really wasn’t my bag. A few years later on I discovered what Mike Mignola was doing in Hellboy and was sucked back in - I think you can see some of his influence, particularly in the early volumes of Olympians. There’s lots more I could mention, sometimes for very specific details - Keith Giffen for textures, Kevin Maguire for facial expressions (of course), Rick Leonardi for his dynamism, Steve Lightle for his shading. Bill Watterson wasn’t a superhero artist but I feel like his stylistic touches are all over my work...

Other people will often point out things in my drawing that I didn’t pick up on myself - John Byrne has been pointed out in the past, for example. He’s not someone I consciously emulated, but lord knows I’ve read enough John Byrne comics that it makes sense his influence would be in there.

As well as the art style being inspired in part by classic superheroes, the Greek gods themselves—as beings with greater-than-human powers like lightning, animal transformation, speed—seem themselves part of the superhero tradition (and indeed, there are many superheroes who are directly inspired by or receive their powers from Greek gods, like Shazam and Wonder Woman). How much are superheroes part of your personal comics history, and how did that play into the way you told these stories?

Despite my love of Greek mythology, the comic characters who were most directly influenced by it were not necessarily my favorites. I think this was at least in part because I was a weird, pedantic little kid and I’d already formed some very concrete ideas about how the Greek gods should be portrayed, and I felt the existing versions in most comics failed to achieve that. Like Shazam, with his rampant mixing of mythologies - what was going on there? The Greek Zeus and the Roman Mercury in the same equation? Pick a side! And don’t even start me on what Solomon is doing in there. Wonder Woman’s depiction of the gods was more palatable to me, especially during the George Pérez era, but they still never seemed… super enough. That might be the peril of sharing a universe with Superman. If a mere average Joe from Krypton is on a level with a god, or higher, well, the Olympians just don’t seem very special in comparison.

As I alluded earlier, I was more of a Marvel kid, and I kind of always liked that Marvel had never developed the Greek pantheon as much as they had their Norse. That said, I was and remain a fan of Marvel’s Hercules. I always felt that character was a pretty nice translation of the mythological Heracles—a boisterous, sometimes buffoonish guy out for a good time—cast in a superhero comic.

The Greek gods are always fighting, having sex, making various terrible decisions, turning into animals - their stories are very reminiscent of soap operas (maybe not so much the turning into animals). How much do you feel that plays into your storytelling approach?

I think we can agree that one of the biggest problems with soap operas is the lack of animal transformations.

All the rest of that stuff you mentioned is very human, very emblematic of the human condition. My whole take on the Olympian gods is that they are an abstraction of a real human family. More powerful, better-looking, but still filled with the same craziness, the same pettiness, the same general family-ness of it all. That inherent drama makes for a great storytelling engine, while at the same time it makes the gods very relatable. They are an enormous dysfunctional family of perfect, imperfect gods. Many other retellings of myth have placed the Olympian gods at an arm’s length - we tend to view them from the perspective of fellow humans, or as heroes. In my books, I cut out the middle people and placed the reader right in the midst of the family squabbles.

I’m curious about how you decided to approach the role of women (and goddesses) within these stories. Your story of Persephone gives her much more agency than any of the versions I read as a child - and Hera has a much greater role in these stories, too! How did you put together the classic myths, the role of women in Ancient Greek society and women’s lives today to create your depictions of these characters?

There were a few instances where I very specifically set out to uncover the female side of things. I have a line I wrote in Hera [Olympians Book 3]: “there is a story they tell of Hera…. It is a story that only the women knew, for when the men of ancient Greece wrote down their stories, they did not think to ask the women theirs” - this is totally true. A little digging around can reveal a lot that was once known and is now lost. Ancient writers will make offhand allusions to versions of stories that were doubtlessly known by everyone back in the day, but now we can only piece together what remains.

Persephone was deliberate - I placed myself in her situation. In all the original Greek versions of the story, it’s really her mother Demeter’s story, or her abductor, Hades. Persephone is a prop, a piece of property to be bartered away or stolen. I thought about what it would be like to be her - the goddess of spring, but always under the protective wing her mother, the Great Goddess Demeter. How would that feel?

As I read more, I noticed something interesting: after her famous time split is worked out—six months in the Underworld with Hades, six months on Mount Olympus with her mother—we never really encounter Persephone on Olympus again. Whenever she appears in a subsequent story, it's in her role as the dread queen of Hades. Like, maybe she started spending more than just six months a year down there. This got me thinking… what if Persephone likes being in the Underworld? What if this was the only way for her to grow from beneath the shadow of her mother, the goddess of grain? To make it simple, Persephone is a seed, and seeds need to spend time underground in order to blossom. This informed my retelling of the famous abduction myth (probably the most famous Greek myth of all, by my estimation), to cast a little light on Persephone, to give her some agency, and maybe make her play a role in her final fate.

You’re writing these books in a way that’s accessible to kids - with a short format and clear language. And First Second is publishing them explicitly for kids. But your books are also full of sex and alcohol and murder and lots of blood and gore (which, of course, are part of the original stories too). How do you take that content and make it work for an audience of elementary and middle schoolers?

A big part of it is that, by virtue of my covering Greek mythology, I get a free pass. It’s classic, so it’s legit. A story I made up whole cloth with similar content would be more likely to get flagged, I think.

I try to never tone down the more “adult” aspects, or clean up the stories to protect those delicate sensibilities. Basically, my one concession is that I don’t draw explicit nudity. As a visual medium, comics are in a unique place to get noticed, and therefore censored. Just look at what’s happened with Maus and that school district in Tennessee recently.

You’ve talked to a lot of kids all around the United States about these books! What’s been kids' response to the books? And how do you think about the kid audience when you’re conceptualizing the story and art for these books featuring very adult characters, with subjects that we sometimes think of as adult?

Not just around the United States - I’m writing you this response while I visit a school in Germany! Greek mythology is an incredibly popular topic for kids, and I think one of the reasons is why I was initially drawn to it. These stories are dark, intense, violent, and sexy - all things literature for children usually tends not to be, but that kids, at least some kids, desperately want to read. We like to push our boundaries by reading and experiencing scary things in a safe way, and Greek mythology is a great outlet for just that.

Which god is your favorite, and why?

After all this time, it’s still Hermes. I’ve always been partial to super-fast characters, like Flash and Quicksilver, and Hermes was the prototype for them. Moreover, he is the trickster god of the Olympians pantheon. Tricksters make for the best stories - they are the smartest characters, but they pretty much only use their powers to either cause mischief or get out of trouble, often in humorous or ridiculous ways. I write Hermes like he’s Bugs Bunny, but without the Brooklyn accent.

What are you working on now? I hear that the Norse gods may be on your list?

They sure are. I’m currently hard at work on the first volume of a four-book series covering Norse mythology called Asgardians. It’s very much the same formula as what I did with Olympians - presenting a sampling of myths in graphic novel form that paint a picture of a specific god. However, given that the corpus of surviving Norse mythology is so much more slim than Greek, Asgardians is going to be a much more comprehensive overview of Norse mythology, even at only four books. Basically it’s going to be Odin, Thor, Loki, and then I kill them all in Ragnarok.

I’m interested in doing other stories as well, stories that have nothing to do with mythology, but the siren call is strong. Nothing is officially signed yet, but I do hope to return to the Greek well in the future. I enjoy these examinations of storytelling too much to give them up. By the nature of the series title, I had to narrow the purview of the stories I covered in Olympians to myths that were concerned, more-or-less, with the big-twelve-or-so Olympians, and there are still so many stories left to explore - stories about heroes and monsters and minor gods and goddesses. Stories like Orpheus and Eurydice, or Icarus and Daedalus, or Eros and Psyche, or Bellerophon, just to name a few. With luck, I’ll still be drawing comics about Greek mythology for years to come.