- Frank Miller, 2014 blog post

“Wake up, pond scum. America is at war against a ruthless enemy.”

- Frank Miller, 2011 blog post

* * *

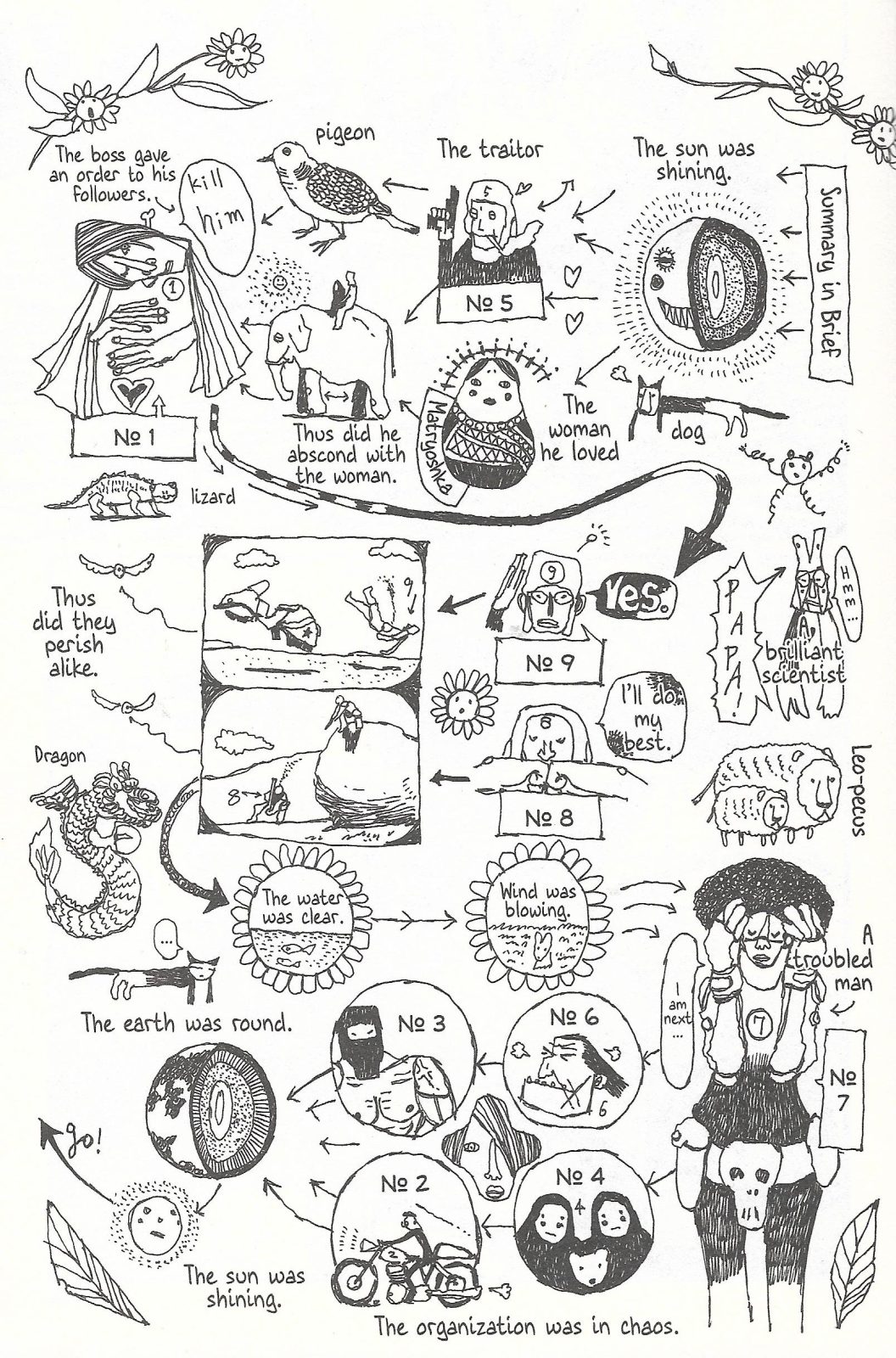

On November 30, 2000, the first chapter of Taiyō Matsumoto’s No. 5 appeared in the first issue of the manga anthology Spirits Zōkan IKKI. In it, a man named No. 5 kills No. 9, a fellow member of the International Peace Corps’ Rainbow Brigade. The rest of the Rainbow Brigade pray together after they feel the psychic shock of No. 9’s death and worry for the trepidatious No. 8, the next member sent to take No. 5 down. Meanwhile, No. 5 and the mysterious woman he has kidnapped dance in the desert in front of a giant moon while a lizard looks on adoringly, accompanied by a diagram of their steps.

Also in November of 2000, a gang in London attempted to use a JCB to steal a diamond collection, which included the Heart of Eternity and the Millennium Star, from the Money Zone area of the Millennium Dome, only to be foiled by 80 disguised members of the Flying Squad. When No. 5 begins, it feels built for a world where the news is full of that kind of sentence. It is mysterious, glib and thrilling, prompting a million questions while radiating the confidence to know any kind of concrete answer will spoil the fun.

Volume 4 of VIZ's new translation of No. 5 collects the last 11 chapters of the story. The final chapter was published in Japan on January 25, 2005, in what had by then been retitled Gekkan IKKI. Five days prior, George W. Bush announced “the best hope for peace in our world is the expansion of freedom in all the world,” after being sworn in for a second term as President of the United States. No. 5 ends as a comic for a world choking to death inside that kind of sentence.

Summaries of No. 5’s labyrinthine plot are available on the VIZ website, but to focus on it may be missing the point. Each volume of VIZ’s current release—actually their second crack at the series, following a disastrous 2002-03 attempt I will describe a bit later—features a wraparound cover taken from one of the two original Japanese volumes it collects, with the cover of the other available as a back-page foldout. The only text displayed is the title, volume number, author, publisher and barcode. Prospective readers must figure the rest out for themselves.

This is the vibe of all the current physical editions of Matsumoto's work through VIZ, echoing the original Japanese releases. The somewhat lofty presentation suggests both pure confidence in the art and resignation that there’s no appeal for the casual consumer. If you know, you know; and if you don’t, we can’t help. This suits the reputation of Taiyō-Matsumoto-in-English as an underrated maverick whose art and storytelling are indisputably both genius and a bit of a hard sell. For fans like myself, it’s tough to imagine his art prompting anything less than excitement from anyone who loves comics, but it does take a while to get into translated print, and often doesn’t stick around very long once it does.

* * *

Matsumoto has been making comics for 35 years. His work spans many genres but always maintains a line shimmering with intensity, a commitment to redefining “sensitivity” and the bravery to get a little closer and a little further away from his characters, both literally and figuratively. When talking about Matsumoto it has long been obligatory to highlight the influence of European comics by the likes of Moebius and Enki Bilal on his work. He discovered Eurocomics while covering the Paris-Dakar Rally at the age of 20 and was so taken by the style he considered moving to France. This influence is evident in his character design, the placement of his “camera”, and the ease with which he slips in and out of surrealism.

His work was published in English pretty early for manga, starting in 1997. In this way, Matsumoto is like Junji Itō, another mangaka whose idiosyncratic work was first translated decades ago (from 2001), slowly gaining traction in the west, albeit on a much larger scale. The two also share another, less-discussed parallel: both are married to talented fellow artists, Itō to Ayako Ishiguro and Matsumoto to Saho Tōno. Like Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan, both sets of spouses have been long-term artistic collaborators, yet this is almost never mentioned when their work is being discussed. In fact, both Matsumoto and Itō occasionally receive praise for working without the normal cadre of assistants that support the detail-heavy work of commercial manga.1 Itō’s other assistant is his mother.

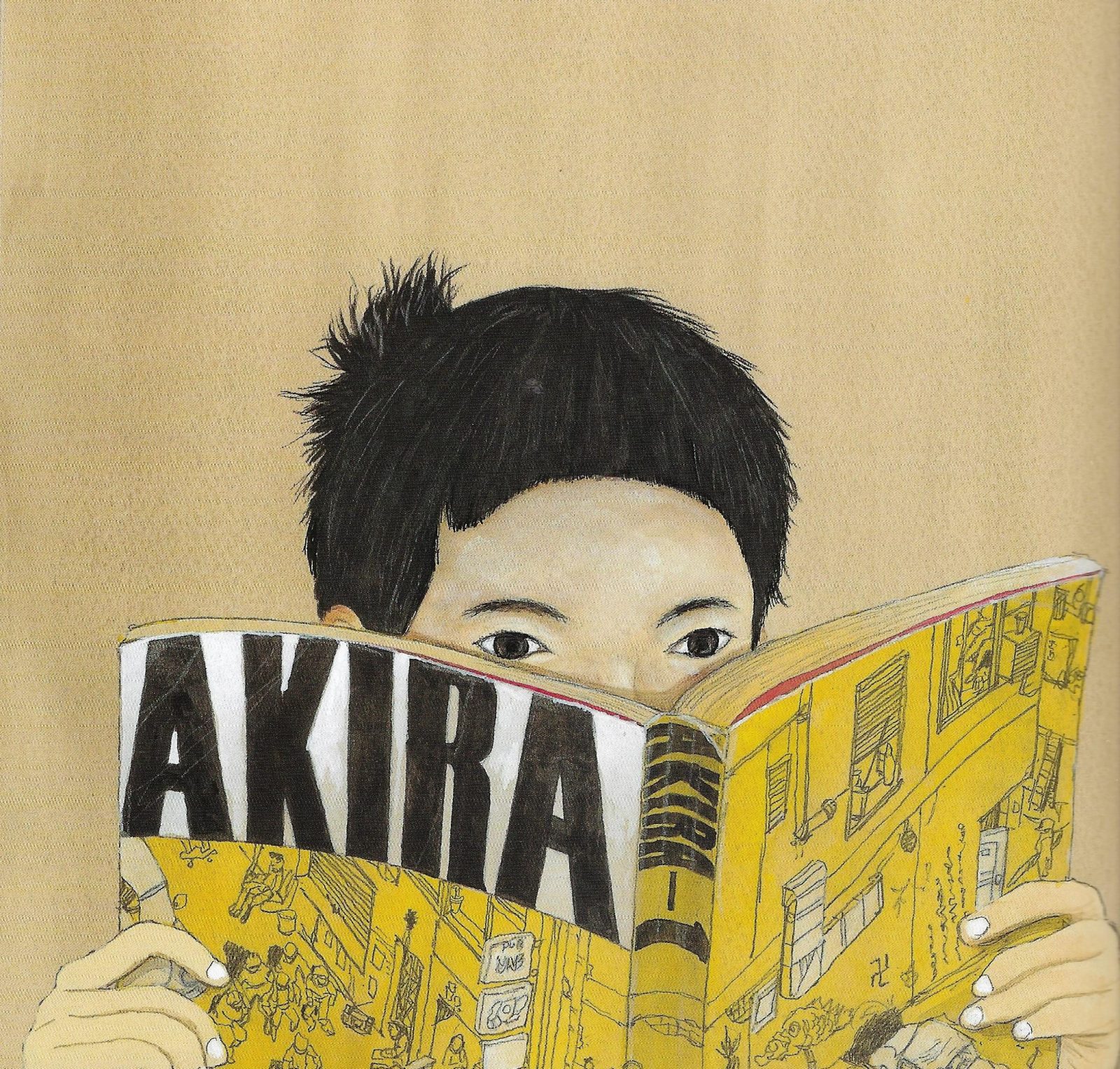

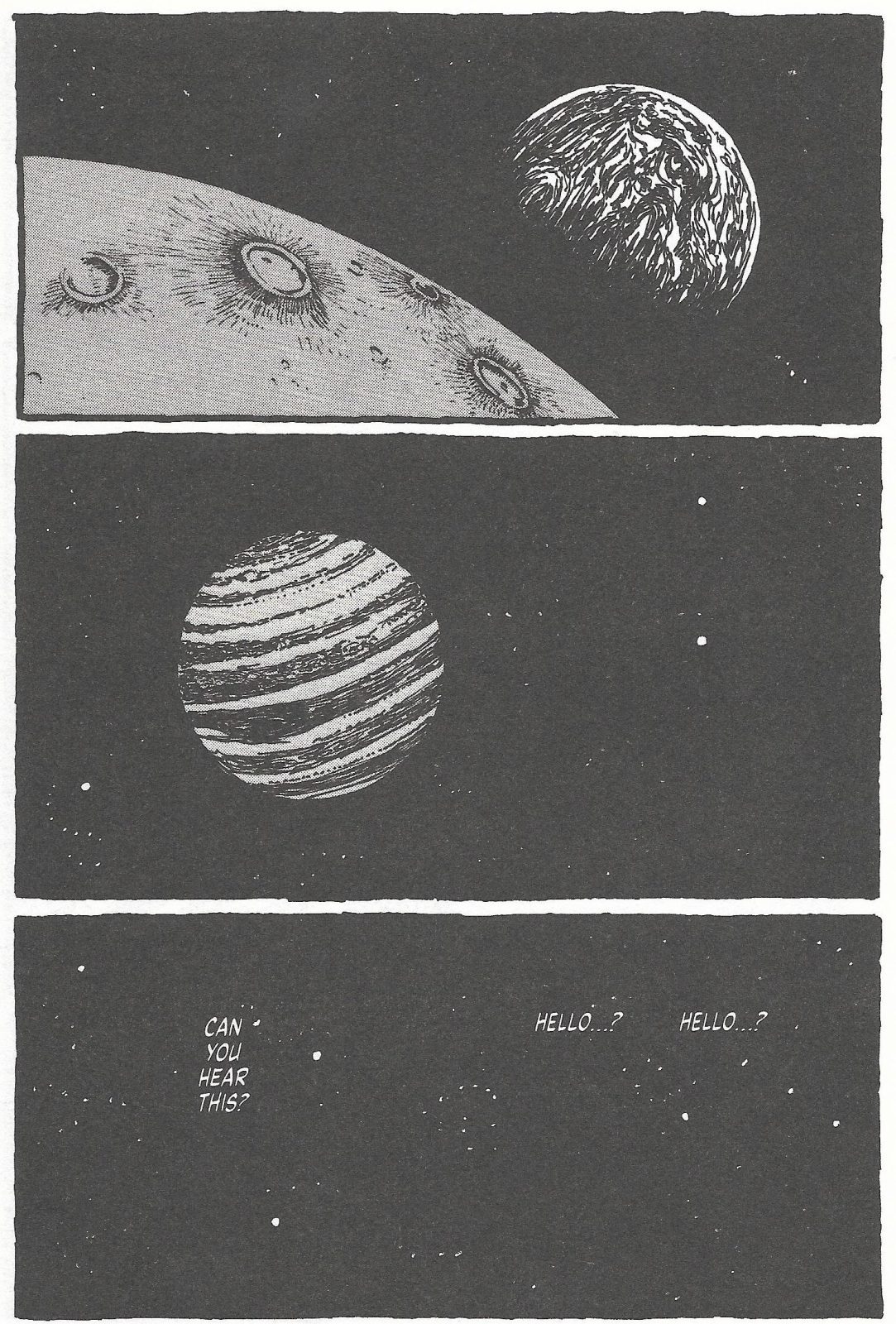

Katsuhiro Ōtomo once claimed that he drew the entirety of Akira with only three assistants. Matsumoto has always said Ōtomo’s work taught him that manga could be “cool” - something else he shares with many western comic fans. In fact, he admires Ōtomo so much that even in 2006, he was afraid to meet him. There’s a characteristic stillness to some of Ōtomo’s action that Matsumoto has mastered and made his own. Occasionally, quieter moments and even pivotal action scenes will eschew momentum entirely and play out more like a traumatic car crash remembered as a series of still images. Similarly, both artists love to play with scale, thinking nothing of suddenly cutting from a close-up grimace to the Earth’s atmosphere with little fanfare. Reading Matsumoto’s work is to look at Ōtomo’s comics through the eyes of Ōtomo’s characters, colored by the oscillating focus and frantic energy of their own perspectives, rather than the god’s eye view Ōtomo himself favors. No. 5 is just as much an exploration of the energy given off by Ōtomo’s Domu as it is a tribute to early Moebius.

Certainly in my case, the early Matsumoto translations fell victim to the era's more incoherent understanding of Japanese comics. When something is first getting popular, be it with an individual or internationally among a community, imposing an orthodoxy on the slim amount of it you have access to is the easiest way to feel like a true fan. Matsumoto’s work is at odds with the pernicious but still not totally obliterated idea of “manga” as a single genre. His tremulous line and willingness to let every element on the page expand and contract in sympathy with the story didn’t match Akira Toriyama’s lush goofiness, the airy precision of Naoko Takeuchi, or the self-conscious perfection of Ōtomo.

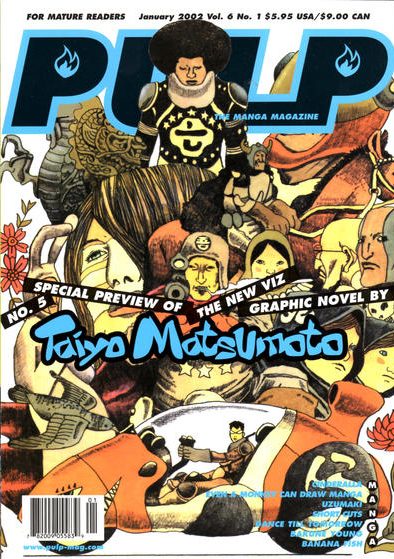

In January of 2002, a 39-page preview of No. 5 ran in VIZ's monthly 'mature readers' manga magazine Pulp, which had anthologized an earlier Matsumoto work, Tekkonkinkreet (serialized 1993-94 in Japan). Retitled "Black & White" at that time, Tekkonkinkreet hadn’t actually completed its run in Pulp; after its slot was taken by Toyokazu Matsunaga's Bakune Young, "Black & White" wrapped up in its own monthly comic.2 Referencing the “injustice” of Matsumoto's serialization troubles in an editorial, Pulp's Alvin Lu expressed hope that the preview of Matsumoto’s forthcoming No. 5 graphic novel “rectifies things a little” and hailed its release as a “new record in translation timeliness”; the series in Japan had only released its first two collected volumes by then. After those two volumes reportedly sold less than 1,000 copies combined in English, the project was canceled.3

In January of 2002, a 39-page preview of No. 5 ran in VIZ's monthly 'mature readers' manga magazine Pulp, which had anthologized an earlier Matsumoto work, Tekkonkinkreet (serialized 1993-94 in Japan). Retitled "Black & White" at that time, Tekkonkinkreet hadn’t actually completed its run in Pulp; after its slot was taken by Toyokazu Matsunaga's Bakune Young, "Black & White" wrapped up in its own monthly comic.2 Referencing the “injustice” of Matsumoto's serialization troubles in an editorial, Pulp's Alvin Lu expressed hope that the preview of Matsumoto’s forthcoming No. 5 graphic novel “rectifies things a little” and hailed its release as a “new record in translation timeliness”; the series in Japan had only released its first two collected volumes by then. After those two volumes reportedly sold less than 1,000 copies combined in English, the project was canceled.3

Disregarding the existence of a curious 2010-11 iPad app release and unauthorized scanlations, this new, complete VIZ run of No. 5, entirely re-translated by Michael Arias, scratches a 20-year itch for some of the Matsumoto hardcore who longed to know how the story shook out after those first two volumes. In fact, I’ve seen several critical reactions to No. 5’s release that hinge on this long-maintained curiosity about how the story concludes. There are dangers in that. The box to the German VHS release of Hellbound: Hellraiser II featured a shot of the Cenobites, the series’ demonic FetLife power-users, wearing hospital scrubs. Fans tormented themselves for decades with rumors of a surgical scene somehow too gory even for home purchase. Eventually, curiosity drove fans to ignore the lesson of the series and open the box—in this case a 2016 Arrow Films box set—which contained the deleted footage. It was an unfinished scene of people shouting at each other in a hallway.

No. 5’s status as an object of pure comics power is indisputable. Its plot is on far shakier ground. In fact, it overflows with a particular incoherence emblematic of the era in which it was produced.

* * *

Salvia is a psychoactive plant. When smoked, it is an immensely powerful hallucinogenic. Its effects last between five and ten minutes. If you haven’t, I wouldn’t. The moment has passed. Said moment was the early 2000s, when salvia’s mostly-legal status made it a brutal rite of passage for bored teens. Who else but teenagers would have subjected themselves to a potentially terrifying trip that could easily lead to a permanently altered conception of reality because buying it at a gas station was far more convenient than tracking down the local knife guy and begging him for enough bad hash to give them a mild headache?

Drug stories are universally terrible. However, salvia’s combination of availability, brevity, and a totally unprepared customer base means its trip reports tend to be a bit more compelling than Joe Rogan announcing the DMT elves told him UBI is a bad idea. Take a look at some trip reports and a pattern emerges of unsuspecting adolescents smashed against the enormity of the universe, for good or for ill. Though surely largely fictional, this Twitter thread is full of classic examples - like the person who became paint and viscerally experienced the sensation of drying on a wall, or the unfortunate who got trapped behind their own retina. It is common to briefly inhabit the consciousness of something else, often a notionally inanimate object. It is equally common to think everything is made of vibrating triangles before becoming convinced you are already dead. Both can be useful.

When I was 15, I was handed a bong while sitting in a small clearing in a local park. Five to ten minutes later, I rang my then-girlfriend, adamant I would never even consider—let alone attempt—committing suicide ever again, because I had briefly been a tree and trees can’t kill themselves. I thought of this often while reading No. 5.

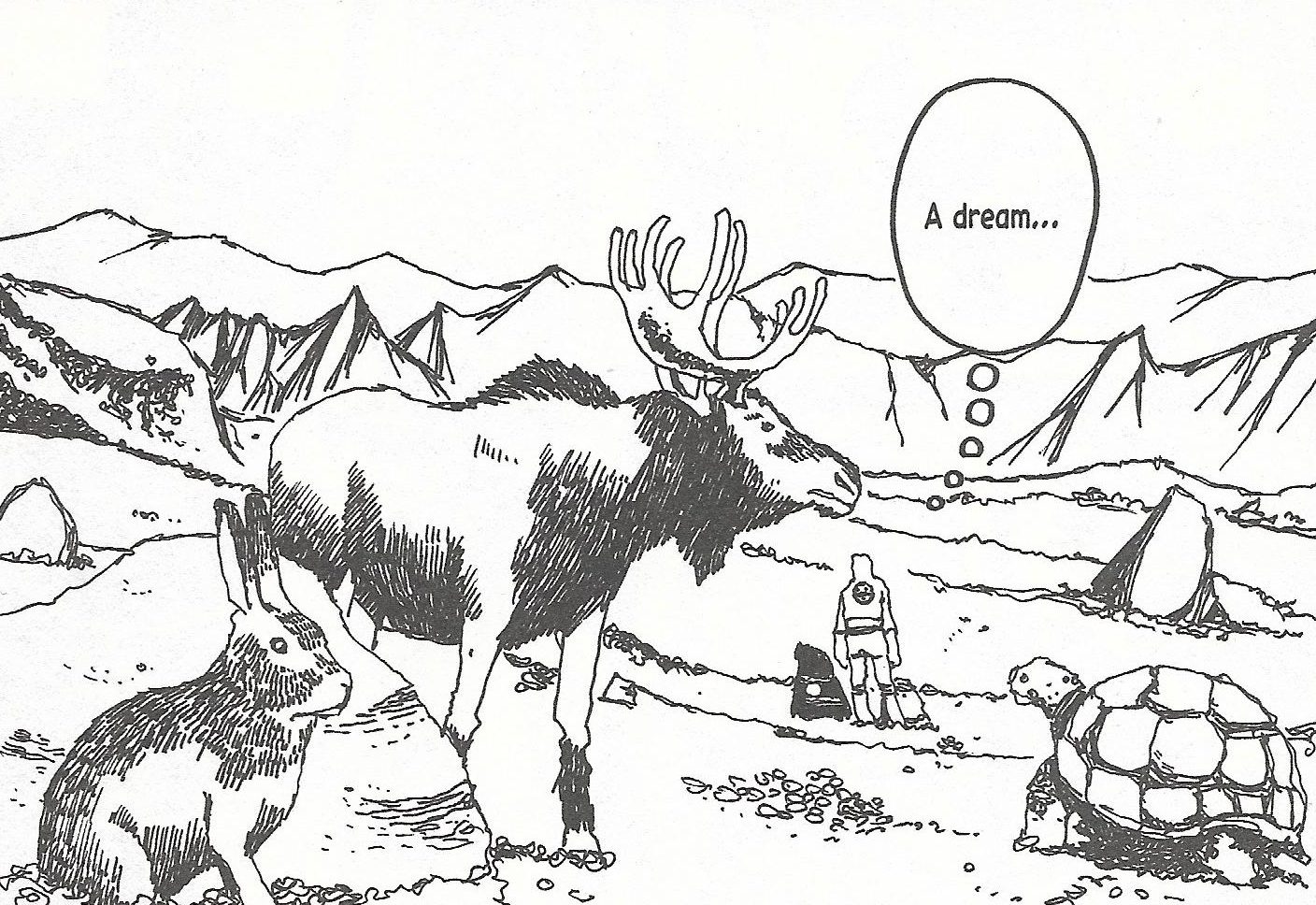

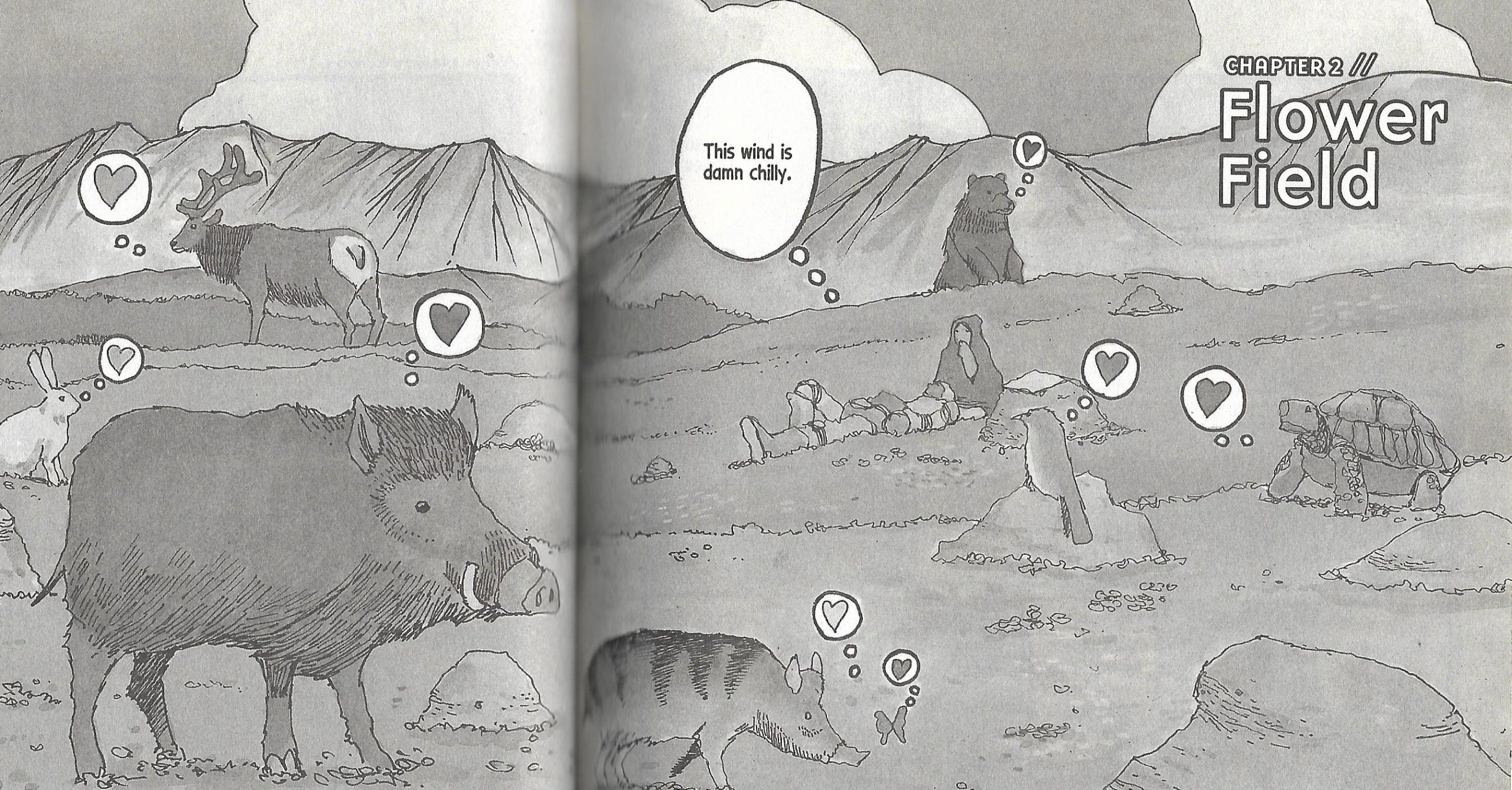

No. 5 teems with animals. We see animals experiencing emotions—either alongside or totally unrelated to the main characters—and we see them think about what they’d like to eat. Rarely does a pivotal moment happen without the steely, unblinking gaze of an animal. This seems cute or quirky initially, but it becomes crucial as the story progresses. You miss them when they aren’t there. Their energy powers the book.

Each of the Rainbow Brigade are genetically engineered super-soldiers, and the mad scientist responsible has also spent his time reviving long-dead species or splicing together existing animals into something new. Fantastical chimeras like tiny hippopotami and leopard-faced sheep abound, all just as curious. Eventually, there are dinosaurs.

I found myself completely ignoring any plot or thematic significance to this, even that of the mystical elk that appears in chapter 0, fixating instead on what the animals might be thinking or seeing. How do they perceive themselves? Are their signifiers for humans in art and in life totally at odds with their sense of self? How are they taking in the events unfolding before us?

A familiar concept when speaking about genre fiction, especially in sci-fi or fantasy, is “world-building”. How deep does the fiction feel? It is natural that a giant, globe-spanning story of world-renowned super-soldiers would feel like the center of whatever planet it’s set on. In fact, most comics—most fictions—tend to feel like this. Even the downtrodden cast of autobio comics feels like the center of the reality they’re presented in. This is because comics are usually created by one person or with one tightly controlled perspective, and centered on the characters to whom we pay the most attention. The constant animal presence propels No. 5 down a different path.

Instead, No. 5 feels like planet-building, or heightened universe awareness. The story of No. 5 is life and death to the characters involved: superhuman beings who can have explosive city-wide fights, and in some cases even bend emotion and reality to their will. But the watchful (or distracted) eyes of all these animals decenter such events. What if this wasn’t the most important thing that ever happened? Would you still care? A bunny-suited super scientist agonizes over creating these soldiers, but isn’t it just as interesting that a quizzical warthog sow is feeling the sun on her skin right now? What other comic regularly makes you feel like spending five minutes behind the eyes of a tortoise as it enjoys a butterfly?

We are constantly wrenched out of the perspective of the amazing action beats of No. 5 and thrown into an idea of what the rest of the planet is feeling and thinking. This is the destabilizing best of the salvia experience rendered in fiction. The sudden jolting awareness—and crucially, an awareness without understanding—of totally foreign perspectives. The sense that everyone and everything has just as much shit going on as you do, organizing the world by what matters to them. The images on a comics page are our single source of truth for a story, governing even the speed at which time progresses. Matsumoto introduces the idea of elsewhere by flooding the page with perspectives we can’t adopt. The “world” does not serve the story; the story is a minuscule part of the universe.

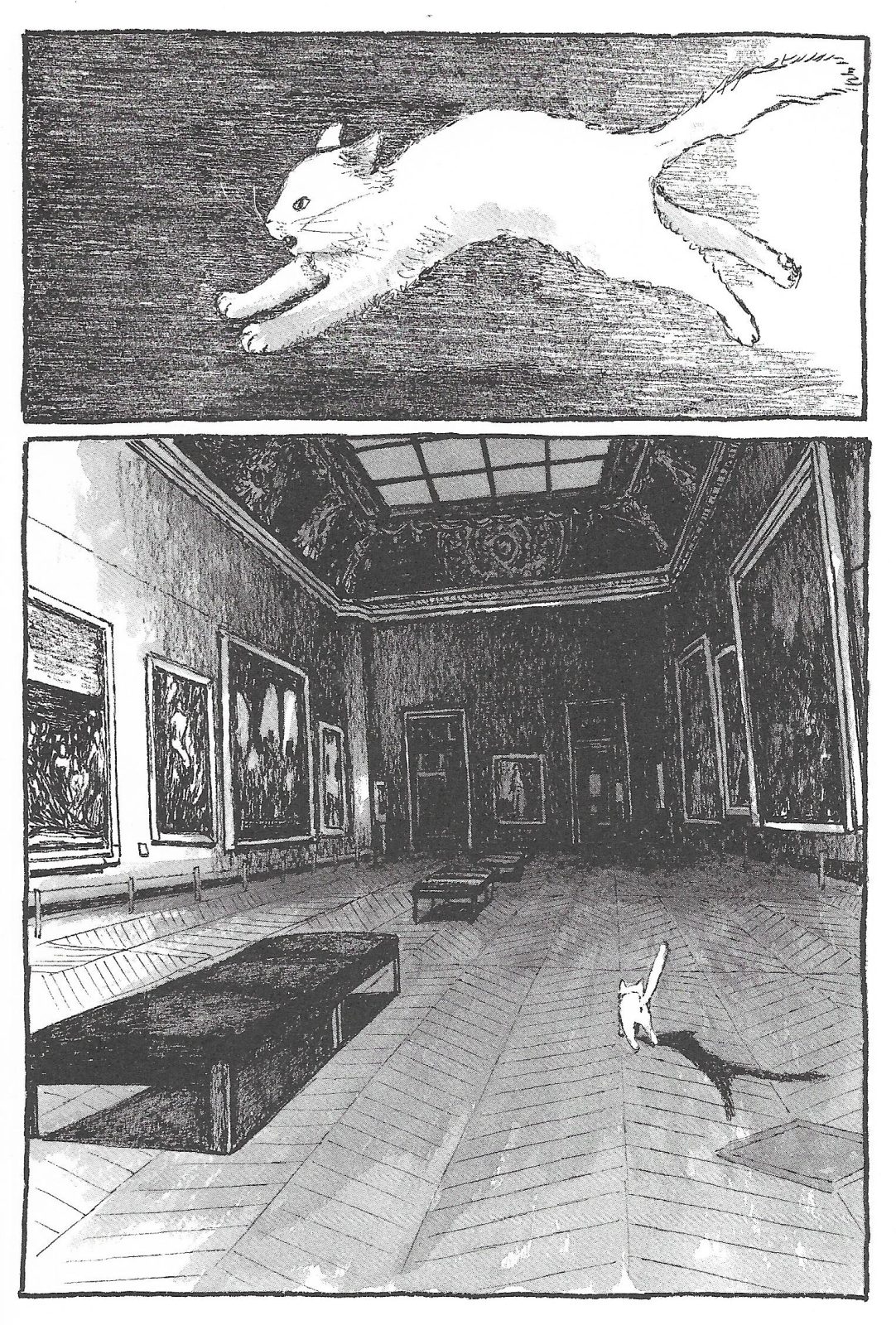

This motif anticipates a later Matsumoto work. A mild salvia-adjacent high can also be found in that ultimate intoxicant: large and largely empty art museums. Matsumoto’s Cats of the Louvre (2016-17) is about death, how cats are, loss, how people are, and what art is for. The cats in question are anthropomorphized when speaking only to each other, but defiantly maintain an animal’s emotional landscape and do not feel like they’ve had humanity mapped onto them. Cats of the Louvre brims with inspired feline gesture, an anti-caricature naturalism of cats being true weirdos. There are scenes set deep within a Mannerist painting, but the book's standout panels remain simple images of cats bounding around the gallery. The Louvre is already warped through Matsumoto’s eye, but seeing these great works of art contrasted with nature and vitality gives a whole new conception of the place.

This isn’t “why not just go look at a tree” bullshit either. Good art galleries present different perspectives in ways that allow them to usefully complicate each other. When looking at one of the giant Henry Moore works in Yorkshire Sculpture Park, the probability that a sheep is also using it to scratch its arse at that very moment is crucial to the experience. Throw the plot of Cats of the Louvre aside and it’s still striking to see a tiny cat rupture the conceit of the august, hermetic gallery simply by existing—like all cats do—as an embodiment of the question “yeah but what about me?”

* * *

The reason No. 5 can cultivate this trippy atmosphere, in its early stages at least, is the unapologetically frictionless way it approaches its plot. It feels like a worthy pretense for Matsumoto to amplify the ever-present influence of Domu, Arzach, and the Super Sentai creations of Shōtarō Ishinomori in his work, marveling at the resulting chaos.

One of the most attractive qualities of the story is who gets to be the titular main character. The focus is not a defending champion, a scrappy underdog, or even a determined hero ready to restore order. Instead, an effective, skilled supporting character is on a rampage only he understands. The early chapters of No. 5 feature a cat-and-mouse game played out on a planet that consists entirely of Moebius covers, full of unexplained history and elliptic ruminations. It feels like parachuting into a book years into its run when the creator has become confident enough to run on pure style.

The first two-thirds of No. 5 mostly rockets along as if it were scripted by prime-era Pat Mills with each element of an endlessly mysterious, exciting world only explained—or often made more opaque—insomuch as it will turbocharge the Thrill-Power of what’s happening right this second. Mills specializes in filling his stories with a weirdness that could be a background joke you never see again, or could become the focal point of a mega-epic. The strongest aspects of No. 5 also have this kind of weightlessness.

In terms of pure excitement, No. 5 reaches its climax during the first half of the third new VIZ collection (or, the fifth of eight volumes of the original Japanese release). No. 3, kitted out in a Kamen Rider dolphin cyber suit, engages in several pitched battles with No. 5 while attacking Rainbow Corps cosplayers in his downtime. Matsumoto takes the smeary, propulsive combat of Tsutomu Nihei’s Blame! and transposes it onto a lived-in city only he could create, complete with agog passersby.

Action detonates across every page in every direction. No. 3 can fly, No. 5 is a sniper. The fight slams effortlessly from long-distance to right up close, showcasing Matsumoto’s complete command of scale and motion. There’s a self-consciousness about the goofy pleasure of drawing two super-beings in combat that sometimes filters into the dialogue, but it always stays on the right side of archness.

It’s not just the constant reminder of animal perspectives that make salvia a good point of comparison for No. 5. At any moment, action sequences can explode into a maze of interlocking triangles. You will totally lose your bearing at first—it’s designed this way—and when you take the time to piece it back together you’ll be rewarded with fresh insight.

There’s a general druggy throb that is central to Matsumoto’s style, “hallucinogenic” but not by the traditional route of swirls and kaleidoscopic coloring. Though a fairly common method in manga, he puts his own spin on how he oscillates the abstraction of characters and objects. More subdued scenes will be completely drawn in pencil, and moments of fleeting joy will reduce characters to happy scribbles. It makes every page an exciting, intimate experiment in looking through someone else’s eyes.

The abortive 2002-03 VIZ release was in a much larger format, similar in size to their eventual phonebook-style release of Tekkonkinkreet (under that title). This generosity served the art particularly well; it’s striking to compare the first volume of the new collection with the preview in Pulp. Though No. 5 comes with a built-in busyness that is undoubtedly charming, the extra space would allow the propulsive action of these later chapters to breathe, and the wide-open desert sections to really sing. In fact, the Pulp preview almost feels like the missing sun-fried step between CF and Stathis Tsemberlidis.

To understand the multi-layer genre appeal of No. 5, consider the numbering of the members of the Rainbow Brigade. There is a reason for this, as Matsumoto has explained: “each 'Number' has a Chinese character phonetically close to their associated number,” like San (3, “disaster”) or Shi (4, “death”). On a more base level, though, it’s a way to instantly understand what’s going on. Be it the adventures of Travis Touchdown or Joe Shishido’s hitman in Branded to Kill, when you’re introduced to your main character, they’ve got a rank and that rank isn’t number one… you can be pretty sure what’s coming next.

Right?

* * *

To understand what happens in the final third of No. 5, consider another salvia trip that took place a few miles and months away from the place and time I briefly believed I was a tree. During the rancid dying hour of a house party, a guy I wouldn’t make eye contact with now if you paid me was encouraged to try it. He began repeating “the shite is… everywhere,” in a slurred, demented voice, before lurching forward and sprinting on his knees headfirst into a TV that was looping the DVD menu of Team America: World Police. He rolled around under the set, trapped in some distant geometric hell, while the DVD tray ejected in grim salute. This is what it was like to consume genre entertainment in the 2000s.

In the early months of the COVID-19 outbreak, many people took to social media to beg others not to make art about it. There’s far too much to talk about when it comes to the assumptions, prejudices and justified suspicions that wind around each other to form the rat-king of this popular sentiment. At least one minor, reasonable motivator, though, may have been the nagging memory of the art that was self-consciously about 9/11 and the War on Terror. The affected solemnity and baffling portentousness of almost everything anyone was doing at that time, all of it in one of three directions, was absolutely suffocating.

Entertainment wasn’t necessarily better or worse before, but the early 2000s was characterized by an almost total focus on “importance” being the end goal over everything else. The overwhelming sense of hopelessness about any kind of protest and resistance coupled with pretty widespread support for bombing weddings created a poison atmosphere of sagacious, useless scolding. There were two Rock Against Bush compilations. I owned them both. Everything felt like it had to make an unambiguous, usually quite glib point in a way the audience could get behind.

9/11 and the War on Terror irreparably mutated popular culture and completely melted many of the already largely-defrosted brains behind large swathes of genre fiction. This “moment” is difficult to explain because it never ended, just metastasized. Now it’s trite to point out that every blockbuster includes collapsing skyscrapers. Or to mention Marvel's most beloved character is a fictional arms dealer. Or even to suggest there's something strange about a popular satire of the dominant medium featuring a character meant to satirize militarism and toxic masculinity who happens to be played by the wrestler who announced the assassination of Osama bin Laden to much of the American public. The guy who wrote Batman for years boasted about working for the CIA in Iraq and Afghanistan and the only fallout involved a blog expressing ambivalence about verifying this information. It was rebutted by the CIA guy’s wife.

This isn’t just comics and superheroes. Every avenue of mainstream western media, thrilled that reports of the end of history had been greatly exaggerated, started grappling wildly with significance as craven militarism become the norm. This is when “funny” was demoted to maybe the 8th or 9th most important thing about stand-up comedy; every nihilistic slacker became a wicked satirist. Now, over 20 years later, there are too many Navy SEALs turned motivational speakers to count, because that’s the ultimate ideal of a human being. Until someone at A24 invented “trauma” in 2015, every gory horror film was somehow about Abu Ghraib. The guys who shot bin Laden all argue in public about who actually killed him like they co-wrote a one-hit wonder.

This is just what everything’s like now.

If this also seems very U.S.-centric then yes, that is also part of the problem. In the late '90s, wars raged all over the world; but for blockbusters, and much of the public, they were distant, almost ambient massacres. Threats in the Nokiawave thrillers of the late '90s came from within, be it unchecked institutions, the festering deep state, or the growing (correct) fear some guys who had the time to figure out computers slightly ahead of everyone else would reshape reality. When the top of the world’s pop culture funnel, however, is suddenly flooded with incoherent rumination about consequence and fear of The Enemy, it’s naturally going to pollute everything else. That’s not even discounting how this massive boost in the U.S.'s already strident militarism affected the rest of the globe. The War on Terror allowed for Japan’s Self-Defense Forces to become a lot more bullish. Ireland’s notional neutrality was sacrificed to become a glorified U.S. military landing strip. This shit is everywhere, and it seeped into everything.

When speaking about No. 5, Matsumoto has said as the work progressed, he “was very much influenced by the social climate at the time, and after a while I didn’t really know where I was, and I considering stopping altogether. After the serialization in [IKKI], my wife and I spent a lot of time going over the series, and we decided that never again we would write something in this manner.” That means yes, No. 5 eventually turns into a rumination on the War on Terror. This is not to say Matsumoto is “unqualified” to write about a political climate, or that comics should shy away from what’s happening around them. Quite the opposite. It’s just that the po-faced register of almost all post-9/11 genre fiction, especially involving superbeings, proved inescapable. All that somber posturing sounds the same, no matter who is involved.

Throughout No. 5, it’s made clear the Rainbow Brigade and their followers are mere mascots and don’t have any practical military value. After all, what use is a champion grappler when someone at a video game console can guide a drone to level any school they choose? If you think you’ve heard this before, you have.

Matsumoto has spent his career picking up different genres, subjects and even styles while always tuning them to the same deeply-felt frequency. Each significant moment for a Matsumoto character is something you feel in your guts. This is mandatory for those who want to excel at sports manga in the way he has with works like Ping Pong (1996-97). Grand statements may materialize, but only as a byproduct of a greater understanding of the people that fill the pages. Ruminating upon on global events and hitting the “when you think about it, superheroes who help the government are basically PMCs and weapons of mass destruction” beats just doesn’t suit him.

* * *

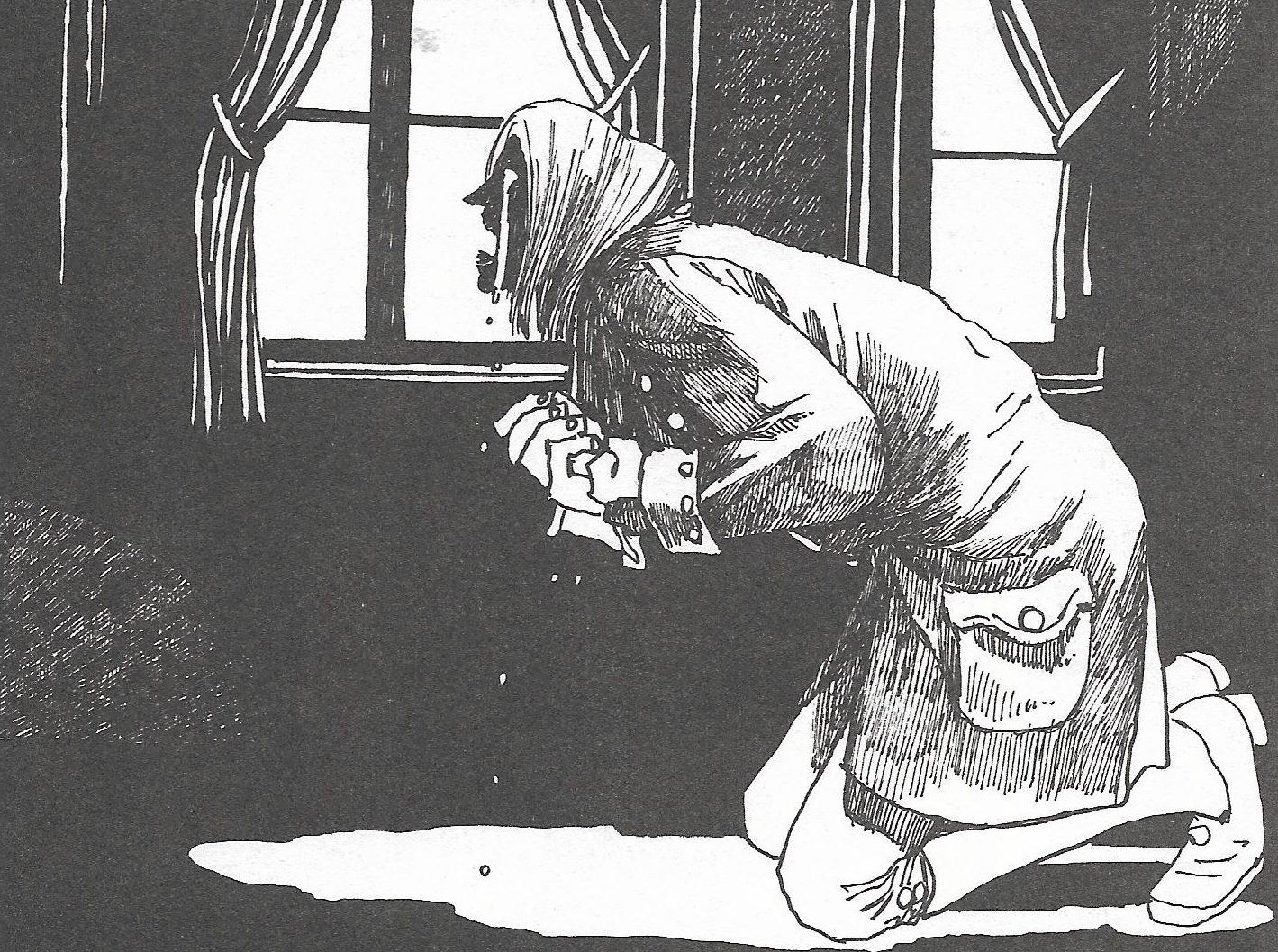

In the back third of No. 5, the titular character disappears for what feels like a volume or two after his explosive showdown with No. 3. The story refocuses on No. 1, aka Mike, No. 5’s very own weeping Doctor Doom. Seemingly invincible Christ-like Mike wants utopia at any cost, and begins to kill off members of the Rainbow Brigade while demanding the dissolution of the world’s armed forces. Even when No. 5 returns, his role is reduced to rhyming with Mike, subjecting the reader to interminable stretches of '90s Vertigo Comics plod. Mad scientists monologue about what they were actually doing this whole time, while guys who feel as though they have barely featured in the comic deliver solemn speeches. No book could survive this sudden trudge through flashbacks and weighty silence. It sucks.

Mike actually feels like an ill-advised inversion of Goshima, the main character of Matsumoto’s second longform work, Zero (1990-91), a sports manga about an undefeated boxer searching for a worthy final fight to end his career. By centering the story around a character like this, Matsumoto sets himself the seemingly insurmountable challenge of finding a way to resolve a character that, on the face of it, defies satisfying progression. The creator has become another opponent for Gohsima, and we root for Matsumoto through every panel - and when the story is eventually swallowed by its main character, it is on Matsumoto’s terms. Matsumoto has said he much prefers drawing to writing stories. That’s totally at odds with how his work feels.4 The plot, the characters, the quiet moments, the dialogue, the art - it’s impossible to consider any without the others. This is certainly true of Zero, which moves with the timing and mechanical precision of a well-delivered haymaker. Of course, sometimes punches don’t land.

Rather than as a personified storytelling obstacle, Mike reads like an author analog. His powers give him seeming omniscience, so that No. 5 tends to cut back to him whenever a significant event happens - and no matter where it happens, his psychic powers have already made him aware of it. Mike can generate empathy, implant visions into people’s heads, and control people by imposing narratives on them. The trope of a character whose power amounts to knowing the ending of the story is pretty common in sci-fi, but it truly sucks the life out of something that began so vital and loose.

Matsumoto has stated that No. 5 eventually became a book about how multiple philosophies must co-exist and no good can come of a single dominant viewpoint. What a pity this becomes bitterly funny as the story falls prey completely to the War on Terror template. In some senses, it almost feels like it is purposefully ripping its most appealing elements apart. Matryoshka, the enigmatic woman who accompanies No. 5, has her origins explained in great detail, missing what could have been a perfect question mark to leave in the middle of the story. Even the elegant system of numbering the characters goes haywire. It turns out that in the past characters have held different numbers, leading to indecipherable descriptions of which number who was when.

Yet No. 5’s descent into tedious cod-philosophic hand-wringing doesn’t mean it’s a complete number two. A comic categorically cannot be bad when it looks like this, and as the violence heats up Matsumoto continues to pepper the reader with careening panel borders and '90s music video angles. Every few pages you're seeing something you've never seen before - that's more than you can ask of most art. Among other things, the scenes with armed battalions camping out around Mike’s castle makes me think Matsumoto could produce a pretty amazing adaptation of Fires on the Plain if he wanted, which he almost certainly does not.

Admittedly, the art does take on a different quality as the story turns. The final VIZ volume of No. 5 strongly recalls, of all things, the most self-serious sections of Kōta Hirano’s Hellsing. After all, when a long-haired superbeing is monologuing and screaming in his castle while masses of disturbed soldiers rend their garments and shadows roil and mutate like a Kelley Jones Batman cape, what else is there to think? Gone is the louche, globe-trotting mayhem of No. 5’s beginning; in its place there’s the self-serious vibe of every other piece of fiction asking “hey, but seriously, who’s watching those watchmen?”

* * *

My mother's cousin used to cut and engrave tombstones. Close examination of the small, beautiful water feature at the front of his house, which looks over a vast expanse of countryside, will reveal some barely-visible writing. It is made of botched tombstones. No. 5’s final climax and its delirious, Malickian coda feel like this. Just before it ends forever, the book in its final chapter allows itself to be totally overrun by the contemplative presence of the animals and nature that had been silently observing the main story all along. Everywhere and everything floods its pages, no longer hemmed in by soliloquies and meaningful looks.

This brief, beautiful respite alone is worth not abandoning No. 5 when plot threads are dropping off at random as Mike smiles serenely at regular intervals. For one final, beautiful moment it put me in mind of the weeks after that salvia trip when I would occasionally look at a tree, think “this guy gets it,” and feel as much peace as a 15-year old in a Clockwork Orange t-shirt can feel.

Sometimes you don’t need the long trip with the message at the end - what Hunter S. Thompson described as that “desperate assumption that somebody—or at least some force—is tending the Light at the end of the tunnel.” A short dizzying hit of dislocation and pure energy is best. Maybe a lab-created alternative that slipped under the radar is better than a grown-up, storied experience weighed down by cultural baggage. Perhaps too, the mystery of a publication with an ending lost to time creates expectations that are too high to ever be met. And maybe rerouting your story about nothing into a parable about everything will deprive it of space, crowding the reader out with the wrong kind of ambiguity.

Before pivoting to the diseased early 2000s zeitgeist, No. 5 was intended to be a fun tribute to some of Matsumoto’s favorite influences. Many of these he originally encountered in French, a language he couldn’t read at the time. Keep this in mind during the final volume of No. 5. It functions infinitely better as a collection of pure image, pacing and geometry than it does a tale about the nature of heroism and peace. In fact, perhaps the uninitiated are best prepared by those enigmatic covers with key events from the story dotted around a landscape, on equal footing with the ever-present curious menagerie.

The character of No. 1 was programmed from birth with an unachievable idea of utopia he felt duty-bound to pursue to the bitter end. When I finished No. 5, I couldn’t help but think of the group of people who’ve spent two decades pining to hold this entire thing in their hands, in English and on paper. It reminded me of the day I found out trees actually can kill themselves. I looked it up. I thought it was important to know for sure.

* * *

- For the record, Tōno is the first-credited of three studio assistants on No. 5, followed by Issei Eifuku (a longtime Matsumoto collaborator, notably as writer of his 2006-10 series Takemitsu Zamurai) and Junji Niwaya.

- The artist's bio inside the current edition of No. 5 touts Tekkonkinkreet as Matsumoto’s most well-known work. It is out of print.

- As Joe McCulloch wrote in his discussion of No. 5’s publication history: “the face of manga in translation had begun to change by that point; with a growing bookstore presence and the passion of a new, young audience, eager to embrace everything that set Japanese comics apart from the local fare, the classic strategies of seeking works analogous to those already popular in English seemed newly old-fashioned. By and large, these young readers did not want manga that ‘sort of’ looked like American comics, and translations marked by that approach went ignored.”

- Also roughly around the time I believed I was a tree, I read an aside in an interview with Daft Punk. One of them remarked that they loved Jimi Hendrix because they could only hear his music as a complete block; the instinct to pick the individual parts into potential samples just never kicked in. Before and after No. 5, Matsumoto has created work exactly like this.