The Fantagraphics edition of Mort Cinder is the first in a series of volumes reprinting the work of the great Uruguayan cartoonist, Albert Breccia. It is undoubtedly the most significant comic translation project of 2018.

The Fantagraphics edition of Mort Cinder is the first in a series of volumes reprinting the work of the great Uruguayan cartoonist, Albert Breccia. It is undoubtedly the most significant comic translation project of 2018.

The term genius has been thrown around with careless ruin for years but there is no better word to describe Alberto Breccia. He was a consummate artist to the very end. His final work was also one of comics’ masterpieces, an astonishing adaptation of “Report on the Blind” taken from Ernesto Sabato’s On Heroes and Tombs (Sobre héroes y tumbas).

The exact nature of Breccia’s style and technique has been well described by the cartoonist D’Israeli, along with a handful of articles and videos online. Yet it is also important to realize the exact nature of Breccia’s artistic philosophy, and how it has affected the way his work looks. In his own words:

"I think that every story requires a different approach. I don't believe in styles. I don't think a cartoonist needs to have a certain style or a way of doing things so that you recognize him for the particular way he draws ears or noses. It ends up becoming artificial. I think style should dwell in the concept with which we do things...I reached the stage after many years of working and searching for my own graphic identity. I spent many years looking for my own style. When I achieved it, for better or worse, it was my style. But I realized it was useless. It was simply a stamp... And that isn't drawing."

The writing of his collaborator, Héctor German Oesterheld, on the other hand, appears to have been given short shrift, at least in the English language—greeted with modest enthusiasm if not disdain. I have heard Mort Cinder described as a curious mix of science fiction, horror and fantasy; with pulpy, thinly plotted and abrupt storylines.

There have been suggestions that Oesterheld dragged out and improvised the introduction of Cinder because of Breccia’s difficulties with finding the right look for the character—hence the strangely meandering first chapter (“Lead Eyes”). Yet whether this forced discursion truly affects the narrative as a whole is difficult to determine.

While the construction of Mort Cinder has been noted to be a flexible and collaborative effort between Breccia and Oesterheld, there are distinct and recurrent motifs in it which suggests it was not put together for reasons of mere entertainment or with little forethought. If anything, there is a coherence and depth in its plotting which suggests a steady hand at the tiller.

(1) Chronology

(1) Chronology

As Janis Breckenrdige writes in the afterword, “[Mort] Cinder embodies the very history of mankind; he is, in essence, History personified.” The stories in Mort Cinder are triggered by chance encounters with people and historical artifacts. For easy reference, these are the episodes in Cinder’s life in chronological order.

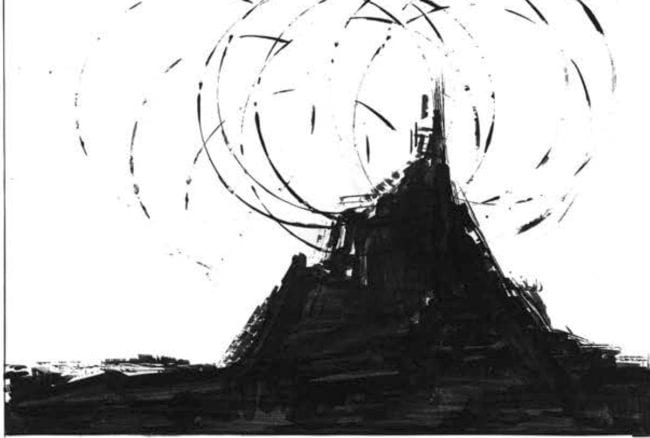

“The Tower of Babel” (Prehistory; Myth). In which Cinder is a captured slave working on the tower. By showing a degree of humanity, he is spared the confusion of tongues.

“The Tomb of Lisis” (Egypt before the time of Tutankhamun, c. 1300 BCE). Cinder is a slave working on the tomb of the Princess Lisis, an ancestor of Tutankhamun.

“The Battle of Thermopylae” (480 BCE). Cinder here goes by the name of, Dieneces, of whom Herodotus wrote:

“…for all that there were so many brave men among them, he that was said to be the bravest was a Spartiate, Dieneces.”

The very same person who when told that the sun would be “blackened” by the multitude of Persian arrows they would face says, “Why, my Trachinian friend brings us good news. For if the Medes hide the sun, we shall fight them in the shade and not in the sun.” His companion is called Alpheus who Herodotus records as being, “after [Dieneces]…the bravest.” Cinder is a slave owner and frees his slave just before the final battle.

“Stained Glass Window.” The Spanish conquest of the Inca empire (1500s). Cinder is a passive participant and a blood sacrifice in his friend’s, Ezra Winston’s, dream.

“The Slave Ship” (1500s). Cinder is a slave on board a slave ship. He makes friends with an African slave called, Wango.

“Charlie’s Mother” (World War 1, 1917). Cinder is a British Infantry man in the trenches of France.

“In the Penitentiary” (Oklahoma, USA,1925). Cinder is a prisoner; his crime unknown. He attempts to help a fellow prisoner escape and is later pardoned when he manages to stop a violent prison riot.

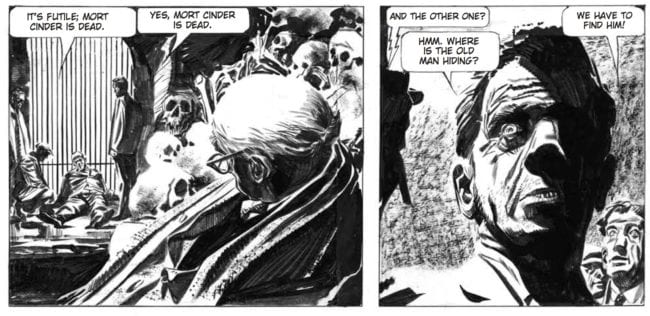

“Lead Eyes” (London, c. 1960). Modern European and presumably South American civilization. Cinder is a murderer who has just been hanged and buried. He is saved by an antiquarian called, Ezra Winston, and is being tracked by a man named, Professor Angus, whose purposes shift with time. Angus seems to be aware of Cinder’s immortality but variously wants to disable him with a stake through the heart and, at other points, to operate on him to gain control of his every thought and deed—perhaps even control over the entire narrative weave and interpretation of history.

In the final segment of “Lead Eyes,” Cinder is found buried in a swamp—has he escaped there or has he been buried by Angus’ men? Perhaps one of the greatest frustrations with Mort Cinder might be seen to be Oesterheld’s elusive plotting; almost purposeful lack of explication; and curious “forgetfulness” with regards motivation and presence of mind (for example, why does Cinder constantly fear for his life when he knows he is immortal?).

At the same time, Oesterheld often provides helpful metatextural commentary at discrete points in the narrative. The single page prologue to the Thermopylae episode presents itself as just this, but only upon rereading. In this instance, Winston has just made a “bad purchase;” a copy of a Greek urn with “too much movement…the Greeks never dramatized like that”—a terse description of his and Breccia’s adaptation of the famous battle if it is compared with the original in Herodotus. In the same breath, he offers a short apologia:

“A copy, when it’s not a forgery is a labor of love. Beside representing the original, a copy attests to the love of the copier. If a copy is good, well then, it’s a work of the greatest art: love. What I wouldn’t give to be able to make a copy like this!”

This is the nature of Oesterheld’s art—it is recursive, often demands rereading and forms a cobweb of meaning across episodes.

(2) Resurrection and Remembrance

(2) Resurrection and Remembrance

The central theme of Mort Cinder is that of resurrection and renewal; a fact openly stated in the pages of the prologue where Ezra Winston asks the reader directly, “Is the past as dead as we believe?”

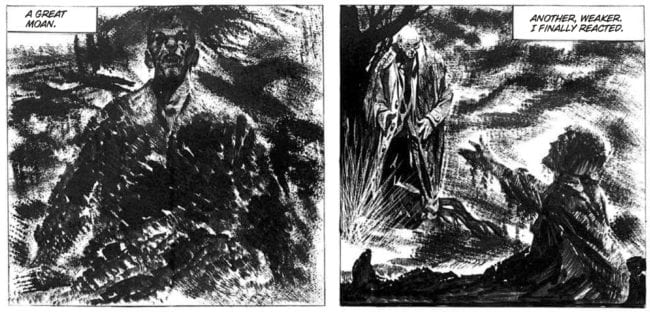

Mort Cinder is of course revived twice in the opening story, “Lead Eyes,” to emphasize just this—his longevity from henceforth is a matter of record and he is never extinguished at any point for the rest of this collection of stories.

Further, there is the scarab which marks Winston’s hand and the path he needs to take to find and revive Cinder—itself a sign of rebirth for the ancient Egyptians. In “The Tomb of Lisis”, an entombed Egyptian priestess is revived by her extraterrestrial lover. A missing soldier returns to his mother in “Charlie’s Mother” and a dead prisoner somehow returns to life towards the close of “In the Penitentiary.”

The underlying meaning of this recurrent motif is more clearly seen when these little awakenings are less physical. In “Lead Eyes,” Ezra Winston is roused from an orgy of fear and anxiety by his new friend, Cinder, and realizes that he has not been betrayed by Cinder or suffered a stroke, but in fact been saved from a kind of lobotomy—a surgical form of mind control which recalls the mind control enacted by the alien invaders in Osterheld and Francisco Solano López’s El Eternauta. (There is little doubt that this is yet another political allegory).

In “The Slave Ship”, Cinder is roused from his “delirium,” his fear of the open sea and his desire to survive a shipwreck at the cost of his African friend, Wango, when he suddenly sees that the latter has sacrificed his arm to save him from some sharks. This is no mere meditation on the impossibility (and desirability?) of physical resurrection but a deeper yearning for cultural and historical recollection—to perceive humanity beyond our own selfish needs, to see memory as the cornerstone of progress.

If we cast our eyes on an Egyptian or Inca artifact, do we simply marvel at the prowess of the ancient artisans of these civilizations or are we also awakened to the cultural history of murder and theft which these objects represent?

In “Stained Glass Window”, an (apparent) Inca priest enacts a curse on Ezra Winston, a hoarder of antiquities who chooses not to pay full value for the goods being offered, a stained glass window. A similar fate awaits the tomb raiders in “The Tomb of Lisis.”

But what exactly is the nature of the curse Winston faces in “Stained Glass WIndow?” Simply the momentary delusion that he has to sacrifice Cinder with an obsidian blade—in other words to kill immortal, personified history. He is saved when “history” in the form of Cinder overcomes him.

(3) Slaves and Slave Owners

(3) Slaves and Slave Owners

In the first story of Mort Cinder chronologically speaking, “The Tower of Babel,” the titular character is a slave working on the tower in question. It is the only story in which he mentions any relatives (“our fathers”) which also suggests his mortality at this point in his life.

As laid out in the chronology of his life, Cinder is almost always in some form of bondage—whether as an actual prisoner in a penitentiary, trapped in the trenches of Chemin des Dames, France, or simply a prisoner of his own honor at Thermopylae. His companions at Thermopylae are not the paragons of masculinity and cultural supremacy found in Frank Miller’s 300 but vile hunters and murderers of slaves, as well as wife abusers.

Cinder is far from an exemplary human being, or at least no more than humanity as a whole can be considered exemplary. Both Cinder and Winston’s rousings from their own selfish needs and fears suggest that Oesterheld was focused on both physical and mental bondage.

Even from the very first, that mental bondage has ensnared Cinder. For instance, he chases a “leper” away from the building site at Babel because he is enthralled by his slavery (presumably a kind of false consciousness) and wants to complete the immense engineering project.

Centuries later in “The Slave Ship,” he almost pushes the slave he once considered his “brother” off a floating piece of wood which can no longer support more than one person. But why is Cinder afraid for his life? If he drowns at sea, is he incapable of being resurrected? Did Oesterheld conveniently "forget" that Cinder was immortal? Or is it Cinder who has forgotten that he is a man?

(4) The Moon Is a Cold Goddess

(4) The Moon Is a Cold Goddess

One of the most consistent and strangest themes in Mort Cinder is Oesterheld’s use of the moon as a symbol for madness, delirium, and forgetfulness—an appeal to ancient etiologies for insanity and epilepsy.

The first time we encounter this occurs during Cinder’s initial resurrection in “Lead Eyes” where Ezra Winston is enraptured by the image of an “immense stone urn, very old, very beautiful. It held a beam of moonlight within it, as though it, too, had been captured by its beauty.” On the face of this urn is the image of “immortal Diana.” It is however a delusion and when awakened by Cinder, he finds only an image of an angel, “utterly worthless, made in the crudest manner”—a reminder to resist the siren call of comforting but false histories (see Winston’s comments on the value of the copier’s art with reference to a modern Greek urn earlier in this article; an example of Oesterheld’s use of recursion).

Cinder, himself, calls the moon “a cold goddess” in the story, ‘Stained Glass Window;” the moonlight streaming though which is the cause for Winston’s murderous intentions towards Cinder. The slave ship upon which Cinder helps to transport slaves is called, The Moonlight. The madness of war and ever present fear of cowardice in the face of danger is enacted on the frontlines at Chemin de Dames (the “ladies’ path”).

The world of Mort Cinder consists of a distinctly male milieu. Women are hardly ever represented in the pages of Mort Cinder—certainly rarely as protagonists and only periodically as victims. In only two instances are they clearly visible: as a forgiving mother in the story “Charlie’s Mother,” and as a silent, static, not quite mummified Lisis in “The Tomb of Lisis;” a fugitive alien who escapes a centuries old, obsessive lover who returns to her side in the denouement to revive her at the cost of his own life.

(5) Blindness, Propaganda, and Immortality

(5) Blindness, Propaganda, and Immortality

As far as internal consistency is concerned, the ultimate source for this “lunacy” chronologically speaking is the beam which the “leper” (an extraterrestrial emissary or hierophant) uses to cast the confusion of tongues at Babel—“an invisible beam that will reach Astarte. She will reflect it, bathing the confused earth in her light”

Cinder by saving this emissary (a disfigured angel if you will) is spared. The alien places his hand on Cinder’s head (“I did not know or understand anything”) and he awakens, possibly immortal though this is never clearly stated in the text—perhaps a sign of Oesterheld’s trust in his readership or unforgiving nature as a dispenser of information.

We can only learn by inference from the events narrated. This is the source of Cinder’s power—he is in possession of the Ur language (the mythical protolanguage) where all others have been blinded; the only one with access to the origins of human nature, genesis, and historical perspective; a return to that hoary adage by George Santayna (here in full):

"Progress, far from consisting in change, depends on retentiveness. When change is absolute there remains no being to improve and no direction is set for possible improvement: and when experience is not retained, as among savages, infancy is perpetual. Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. In the first stage of life the mind is frivolous and easily distracted, it misses progress by failing in consecutiveness and persistence. This is the condition of children and barbarians, in which instinct has learned nothing from experience."

As Megistias, the Spartan Prophet quizzically remarks to Cinder at Thermopylae, “The time will come to sleep for all eternity. And how strange, Dieneces, that you keep watch while the others dream. It should be the reverse.”

In other words, men should keep watch over history, not the reverse. The leaden-eyed figures which populate latter day London are merely a personification of this stuttering vision encased in rigid souls—shrouded in propaganda and misinformation.

But this perspective also suggests a kind of optimism in Oesterheld’s narrative—that historical retention brings about paradoxical change and a civilizing force. This explains the repetition in “Lead Eyes” of Cinder's resurrection narrative—for all intents and purposes a da capo and a variation. By remembering his past and repeating it, Ezra Winston is better able to help Cinder in his defeat of Angus’ brainwashed servants and also comes to trust him (history-memory) absolutely, feeling betrayed when he suspects that he has been abandoned by him.

In his series of essays on Breccia at Down the Tubes , Ron Tiner point us to the writing of Laura Vazquez (Laura Vazquez, Mort Cinder: Memories in Conflict, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 2002) and her suggestion that “the immortal figure of Mort Cinder reminds us of El Immortal of Borges.” Borges short story begins with a quote by Francis Bacon:

“Solomon saith: There is no new thing upon the earth. So that as Plato had an imagination, that all knowledge was but remembrance; so Solomon giveth his sentence, that all novelty is but oblivion.”

Towards the close of the Borges’ story, the protagonist learns the true nature of immortality and that:

“There is nothing very remarkable about being immortal; with the exception of mankind, all creatures are immortal, for they know nothing of death. What is divine, terrible, and incomprehensible is to know oneself immortal… […] …They knew that over an infinitely long span of time, all things happen to all men. As reward for his past and future virtues, every man merited every kindness—yet also every betrayal, as reward for his past and future iniquities.”

I have yet to read Vazquez’s thoughts on Mort Cinder in full but this is a much more pessimistic view of human experience which probably conforms better with our reality—that those who remember the past are condemned to repeat it anyway.

But Megistias the augur—the all knowing prophet, the writer of all these adventures, Oesterheld himself—asks Cinder (and history) to dream and that is exactly what he does. As Cinder calmly explains to Winston at the close of “Lead Eyes”:

“You have many things misclassified, I can help you classify things…I have a long memory, and I remember it all very well. And if you ever doubt me, I’ll return to the past. With you Ezra Winston…Will you hire me?"

This is Oesterheld’s optimism, the heavy but close hand of history, ever ready to classify things, to help us remember, to help us become better, to help us to become free.

Online Reference:

Online Reference:

Laura Vazquez on the political and ideological dimensions of Mort Cinder

“The memories in historical conflict that the immortal possesses are his only and potential wealth. With them he can master the time and space of his actions, but also, and fundamentally, he can interpellate historical events as a subject.

The latter is the fundamental key to the story. Mort Cinder through his narrations will shed light on the vision of the old Ezra, the tacit message of Oesterheld at this point will be: history can be intervened.”