I met Renee Blitz twenty years ago in the hot tub of our health club, where she discussed Kafka while others planned vacations in Tuscany or weekends at Squaw. Renee is eighty-two and a grandmother. She grew up in the Bronx, the tomboy daughter of Yiddish-speaking Orthodox Jews. She graduated Hunter College and married a stand-up comedian who, after moving them to Berkeley, the laughs not coming, became an ass-chasing social worker.

Renee passed her time hanging at dives with a jazz pianist who’d 4-F’d the army and on-the-roading with a salesman whose best attribute was how much fun he was to get stoned with. The surrealist poet Nanos Valoritis recruited her into the graduate writing program at San Francisco State after reading her self-described, stream-of-consciousness “typewriter plays.” (“Get your ass in here,” he said.) He declared Renee the only of his students destined for a career in the theater. She thanked him for the flattery but spent her time raising three daughters.

Her next future ex-husband was Moe Moskowitz, whose bookstore had made him to ‘60s Berkeley what Sylvia Beach had been to ‘20s Paris, if Sylvia Beach had been a bald, pot bellied anarchist who smoked foul cigars. Moe is, of course, known to comic historians for his role in launching The Print Mint, which published Zap, Lenny of Laredo, and Yellow Dog; but Renee’s proximity to the UG did not include reading, let alone writing, them. Her prose did not re-surface until Sitting Shiva for Myself, a collection of dark, savage, comic feuilletons (Regent Press. 2010). It received two reviews, one rave by me, on-line, at Trouble with Comics, and one by a stranger, in The Daily Forward, who lauded her “crazed, wild and despairing Jewish rants” as “the underrated gem of the year.”

When the anthology Black Eye, containing a chapter from my novel The Schiz that I hoped would lead to calls for its entire publication was, instead, ignored by critics, both mainstream and backwater, I thought, What about Renee?

When the anthology Black Eye, containing a chapter from my novel The Schiz that I hoped would lead to calls for its entire publication was, instead, ignored by critics, both mainstream and backwater, I thought, What about Renee?

She handed back my copy with a penciled note. (She also somehow handed me the pencil.)

“I was hoping for a review,” I said.

“For who?” she said.

“I’ll think of some place.”

“Who’ll read it?”

“Lots of people. Dozens.”

“Me? Why? I don’t know if I can write a review.”

We decided on collaboration. I’d interview her about Black Eye. She’d interview me about me. It took place, on a crisp, clear fall morning, beside the club’s pool. Renee wore baggy gray sweats, a towel concealing all but her nose, eyes and mouth. While we talked, she stared into the water’s deep end.

“I still don’t know what we’re doing,” Renee said. “What’s it all mean?”

“Isn’t that always the question?” I said.

.......

BL: So, Renee, you don’t read comics, right?

RB: As a child, I read all the comics in the Hearst press. I loved Dick Tracy. When Dick Tracy had the two-way wrist radio and when Gravel Geritie had the baby, Sparkle Plenty I think it was called, I felt some kind of thrill. I didn’t know what it was, but I thought, Shit, that’s fucking great. Sparkle Plenty, Gravel Gertie, Two way wrist radio; and Smilin’ Jack with the buttons popping off his shirt every minute. It was a relief to me from the world I was thrown into as a child which is to believe in what is presented to you, believe what we’re telling you. And this was a shout saying, “It’s all a fucking lie!” And I somehow got this as a kid. It’s a fucking lie and they’re fulla shit. I was bored shit in school and these comics were a relief. I loved the colors, these words, these concepts. Their world was different. I’d wait at the candy store for hours Saturday night for someone to scream, “It’s here! The paper” because the comics were life-giving for me.

BL: Then seventy-five years later comes Black Eye.

RB: It’s a nice looking book. I like the paper. I like the color. A little note on a contributor might be nice, or a table of contents, but I didn’t miss it.

BL: And the content?

RB: The book was great. It’s all about death. This skull on the cover. This thing, “I Made a Mess of Things” [Author’s Corrective Note: “Oh, I Have Made a Mess”]. This story “I Fuck Dead People.” And these crazy, intense, expressionistic drawings and the message the world in uninhabitable. The world is, as we know it, uninhabitable, spiritually, physically, emotionally, and the question is how do you inhabit what is basically uninhabitable.

RB: Oh yours is definitely about death. You didn’t know it was about death?

BL: No.

RB: I feel all writing is about death. You know what Kafka said? He said something like “Pretend you’re writing from the grave.” You’re dead; you’re in the grave; and that’s the way you see the world – from the grave. Write with the third eye of death. Because it gives significance. It gives significance. It gives significance.

BL: You wrote in your note about these comics “telling truths which are otherwise hidden and prevented from coming out, as if we are imprisoned and held captive by conventional linguistics, without even knowing it.” Explain what you meant by that.

RB: These cartoons are like nothing else. They are trying to say something that even by them doesn’t necessarily get said. They’re trying to say there’s a big block here, a wall of crap, a wall of stone that you can not get through, and they are very brave because they are saying we are going to try. We may not get through but it’s enough to acknowledge we live in death. We have no answer. Our meaning may not get through. We may not even have a meaning, but it’s enough to say there is a wall of death that makes the world uninhabitable. And these comics seem to know that.

BL: When you say “wall of death,” do you mean actual physical death?

RB: I’m talking about the daily death everyone experiences. It is a spiritual death. People know that they are miserable. It’s like the Bob Dylan song, "Mr Jones." [Author’s Corrective Note: “Ballad of a Thin Man."] “I walked into a room with a pencil in my hand. I see somebody naked and I don’t understand.” Or it’s like the Rolling Stone guy [Author’s Corrective Note: Mick Jagger], “I get no satisfaction.” The reason these songs got to people is because it’s the truth. Now I don’t know what kind of death is death. There’s a million kinds of death and they all amount to the same death because ultimately we all know we are going to die but we try to run from it. We try to say no we’re not going to die; we’re going to have fun. But everybody knows, after the fun is over, death rears its head in some sort of terrible dissatisfaction, emptiness, despair.

The book describes itself as a “journal of humor and despair.” You know, I don’t think it’s really that humorous. I know they say that to depart from conventional values and to brazenly put stuff out there is a form of humor. I didn’t find it so funny. I never laughed. It was not a ha-ha humor. It was just the act of saying, “Fuck you and what you’re putting out; I’m not buying it.” And that’s a heroic statement.

BL: You don’t think my story was funny? [Author’s Note: In the published chapter, a doctor who has been suspended from practice supports himself by curing women of a disease he has diagnosed by having sex with them.]

RB: No.

BL: Do you think Nathanel West is funny?

RB: No. I don’t think Nathanel West is funny. I think he’s very serious. I don’t think all those stories write to him ‘I don’t have a nose and nobody likes me’ I read Miss Lonlyhearts a couple of time. It was gripping but I didn’t find it funny. I didn’t find your book funny. [Author’s Note: In a subsequent phone message, Renee clarified her position to say that she now believes “there is a different kind of funny, a mixed funny-sad state, which these stories are, but not a Milton Berle-funny.”]

BL: In your note, you used the term ‘spiritual pornography’ and ‘grief-stricken surrealism’ to describe my writing. Why? They were lovely things to say, but I never thought of myself as creating either.

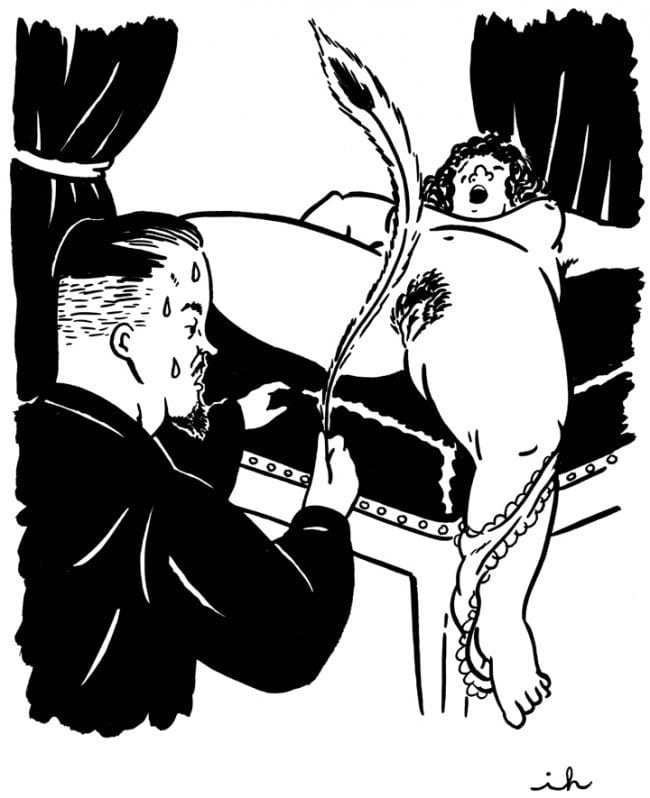

RB: When Dr. Mort is fucking the fat woman with the wart on the nose, on the one hand, he’s digging the fact that she’s a very heavy, not so sexy woman, and he’s getting off on it, but there’s a disjunct in his mind. You don’t know whether he’s a flat-ass pervert, if he’s digging the grotesque, or if he’s suffering the human condition. You know, a lot of people are turned on by fucking someone who’s not the typical beauty. Who’s morbidly obese, who’s maybe crippled. But he’s also in despair because he owes a lot of money. And the drawing’s very sleazy. His hair is like dripping, with some sort of crazy expression on his face.

BL: I loved the drawings...

RB: I loved them too...

BL: I had nothing to do with choosing the illustrator [Ian Huebert] and they weren’t anything like how I had pictured my characters but they added this air of like comic Victorian pornography to it.

RB: Absolutely gorgeous. But the guy looks tortured. On the one hand he’s digging the sex, digging it from a low point of view. And he’s getting back at the medical establishment. But you get the view he’s immensely sad. And you wonder what is the sadness about. It’s very mixed. That’s what makes it powerful. You get the feeling, on the one hand, he’s out of it. He doesn’t care. She’s an object, and he has to pay his alimony, but you get the feeling he realizes that he’s living in shit, that the entire medical establishment is corrupt. He’s aware of the sea of shit he inhabits and he’s perpetuating some kind of sea of shit by doing what he’s doing. He’s a tortured guy. He’s not just a guy trying to earn another buck.. He’s in another trip and part of this trip precedes what had happened to him that he can’t practice for a year. His true essence is coming out. He hit bottom and the bottom is leaking. He’s not just a regular guy getting off. Life has handed him something very hard.

RB: Absolutely gorgeous. But the guy looks tortured. On the one hand he’s digging the sex, digging it from a low point of view. And he’s getting back at the medical establishment. But you get the view he’s immensely sad. And you wonder what is the sadness about. It’s very mixed. That’s what makes it powerful. You get the feeling, on the one hand, he’s out of it. He doesn’t care. She’s an object, and he has to pay his alimony, but you get the feeling he realizes that he’s living in shit, that the entire medical establishment is corrupt. He’s aware of the sea of shit he inhabits and he’s perpetuating some kind of sea of shit by doing what he’s doing. He’s a tortured guy. He’s not just a guy trying to earn another buck.. He’s in another trip and part of this trip precedes what had happened to him that he can’t practice for a year. His true essence is coming out. He hit bottom and the bottom is leaking. He’s not just a regular guy getting off. Life has handed him something very hard.

How do you view that guy?. Is he just sleaze or do you feel him as a person who’s tortured?

BL: When I came to write this thing... The crucial character is off stage at this point you’re reading, the patient Dr. Beujack is about to see. He is a homicidal paranoid schizophrenic who is based on a client I had [when I was practicing law].. At the time I was writing these sophisticated, macabre humorous stories like John Collier. The only I published was in this skin magazine but that’s another story. So, this guy became like this problem. How could I use him in a story? This lawyer meets this guy who’s an untreatable homicidal paranoid schizophrenic, okay. That became my situation. And the doctor was based on this guy down in San Mateo who the papers were calling “Dr. Sex” because he had this deal where he was like treating this women and his treatment was he would have sex with them to cure them of this disease, and I thought, Now what’s that all about? Who are these people? Do they really think they’re getting cured of a disease? I was like collecting these things that were in the world. Homicidal paranoid schizophrenics, Dr. Sex, and I’d go on from there putting these pieces together, trying to expand them into enough length to have a novel. And I thought, I’d do for lawyers and doctors and patients and clients what Nathanel West did for Hollywood. I wasn’t thinking “pervert” or “tortured.” I was more like giving this world view.

Anyhow, why do you want to read more of it?

RB: I’m curious as to who you are, and I think other people would be curious to see... What the fuck? What is this? It sounds like it’s not an ordinary story even though you have the ordinary details of the guy losing his medical license and the wife getting all the money and fucking the lady on the special table from Goodwill. It sounds like you want to reveal yourself. You’re searching to reveal yourself and I want to see who you are.

BL: I’ll definitely bring you the rest of the manuscript.

RB: Good. I have a feeling about you. I have a very deep feeling about who you are. Because I think that you’re a lot like me and want to see how you work with those elements. I want to see how you work. What you do with it.

I think the meaning of being Jewish is a lot of rumination, a lot of depression. The Jews have enormous sadness; their history, it’s all there. In all the writing I’ve ever done, all the ruminations I’ve ever done, all the depressions I’ve ever cultivated, and I deliberately cultivated depression because I felt the depression people had the truth, and you had to be depressed to be a real person stuff. I mean I might have been very depressed anyway; I’m sure I was, but I actively cultivated depression. I had a whole lifetime of cultivating this cheerlessness, dealing with depression, dealing with thoughts that lead nowhere, entertaining myself with thoughts that are total mishegas, craziness, entertaining myself with shadows on the wall. That’s my schtick. Which is ridiculous. The shadows on the wall speaking to me.

The goyim are happy. Like when I was a little kid, there was a tap dance studio around the corner and girls were tapping, with Shirley Temple curls and a dress with a sash on it with big polka dots and tap shoes with big taps, and I said to my mother, “I want that. I want to go there and do that”; and my mother said, “That’s for the goyim.” Then I said, “If I can’t do that, I want to be the high-stepping girl with white boots and tassels, leading the parade, with a really tall hat, two-feet high, with sparkles, and twirling a stick.” And my mother said, “She’s a goy too.”

So I thought what’s a Jewish girl supposed to do? What’s she allowed to do? And later, when people started fucking, extrapolating from what my mother said, I figured out “Blow jobs.” Blow jobs were the Jewish girls specialty, because then you could get married and still be a virgin. And I started writing, because writing really wasn’t a thing to do; it was a thing without being a thing. You could slip it in somewhere and you didn’t have to call it anything. It was a “no-thing,” like breathing or shitting. You don’t say to your mother, “I want to be a breather,” or “I want to be a shitter.” It just happens. Like, “Shit Happens.” Writing happens.