The Italian graphic novel scene has its fair share of eclectic figures, but few are as elusive as Marco Corona. Bluntly put, Corona is weird. And I don’t mean weird as person - even though, don’t get me wrong, he definitely is weird as a person (and I mean that as a compliment). I mean, weird as an artist. Very erratic in style and interests, with works ranging from traditional illustration to experimental visual storytelling. It’s probably no wonder that he's flown under the radar of mainstream recognition for so long (and, in all fairness, still does): Corona is particularly hard to pin down into clear categorization. Looking at his body of work, one may think of it as a collection of unrelated books bound together only by the name on the cover. But, taking his oeuvre as a whole, a coherence of sorts emerges, despite (or maybe precisely because of) its variety.

Corona’s work is deeply personal in nature, both in terms of the artist’s creative aim and the perception of those aims by the reader. Presented with such ineffability, a rational and chronological account of his evolution as an artist may not be the most useful thing. Instead, what I’d like to do here is sketch a portrait of the author: my partial understanding of him, derived from a personal journey through his work. And since we have locked rationality in the drawer and thrown chronology out the window, I will start with his second book.

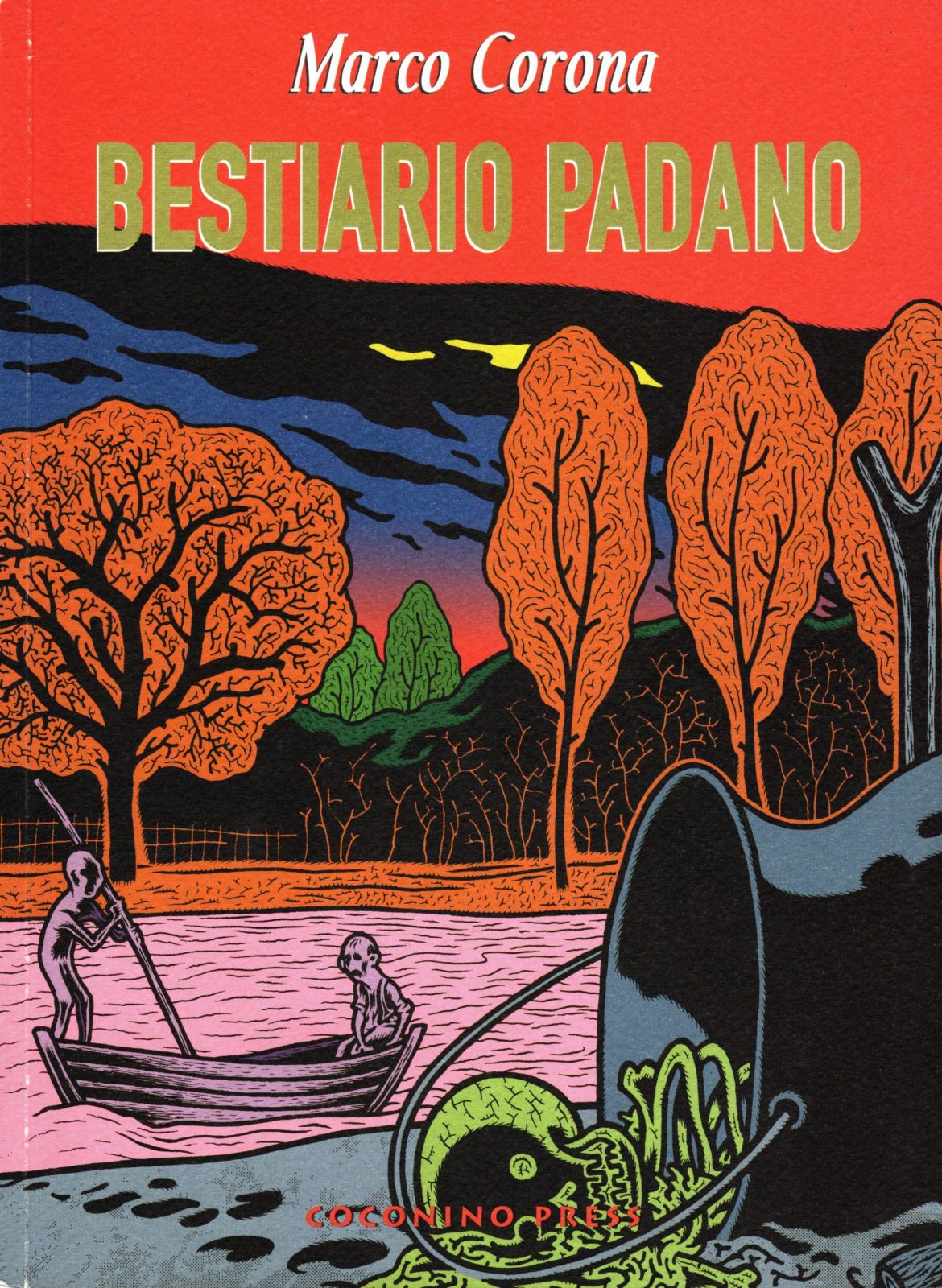

Bestiario padano (Coconino Press), which translates to “Bestiary of the Po Valley”, came out in 2003. At that time, Marco Corona was 36, his name already whispered in reverence by a niche of connoisseurs who saw and appreciated his work in magazines such as Blue and Schizzo Presenta; perhaps they saw his illustration collection, 32 coups de toux, from the French publisher Le dernier cri, or his short story in the seminal anthology Comix 2000 from L’Association. At the time, Coconino Press was “la crème de la crème” of the soon-to-be graphic novel scene in Italy. Under the artist Igort's direction, the Bologna-based publisher was translating and producing the best the world had to offer in terms of high-level visual storytelling, giving birth to a period of growth in recognition and legitimacy for Italian comics that still continues today. I was 13 in 2003. I didn’t know about Bestiario padano, nor anything about Marco Corona - nor, for that matter, Coconino Press. I was too busy reading cheap manga and the occasional superhero story. I’m glad I only discovered Bestiario padano many, many years later. As a young teenager, I would’ve been shocked and confused and repulsed by it. I would’ve hated it.

Bestiario padano (Coconino Press), which translates to “Bestiary of the Po Valley”, came out in 2003. At that time, Marco Corona was 36, his name already whispered in reverence by a niche of connoisseurs who saw and appreciated his work in magazines such as Blue and Schizzo Presenta; perhaps they saw his illustration collection, 32 coups de toux, from the French publisher Le dernier cri, or his short story in the seminal anthology Comix 2000 from L’Association. At the time, Coconino Press was “la crème de la crème” of the soon-to-be graphic novel scene in Italy. Under the artist Igort's direction, the Bologna-based publisher was translating and producing the best the world had to offer in terms of high-level visual storytelling, giving birth to a period of growth in recognition and legitimacy for Italian comics that still continues today. I was 13 in 2003. I didn’t know about Bestiario padano, nor anything about Marco Corona - nor, for that matter, Coconino Press. I was too busy reading cheap manga and the occasional superhero story. I’m glad I only discovered Bestiario padano many, many years later. As a young teenager, I would’ve been shocked and confused and repulsed by it. I would’ve hated it.

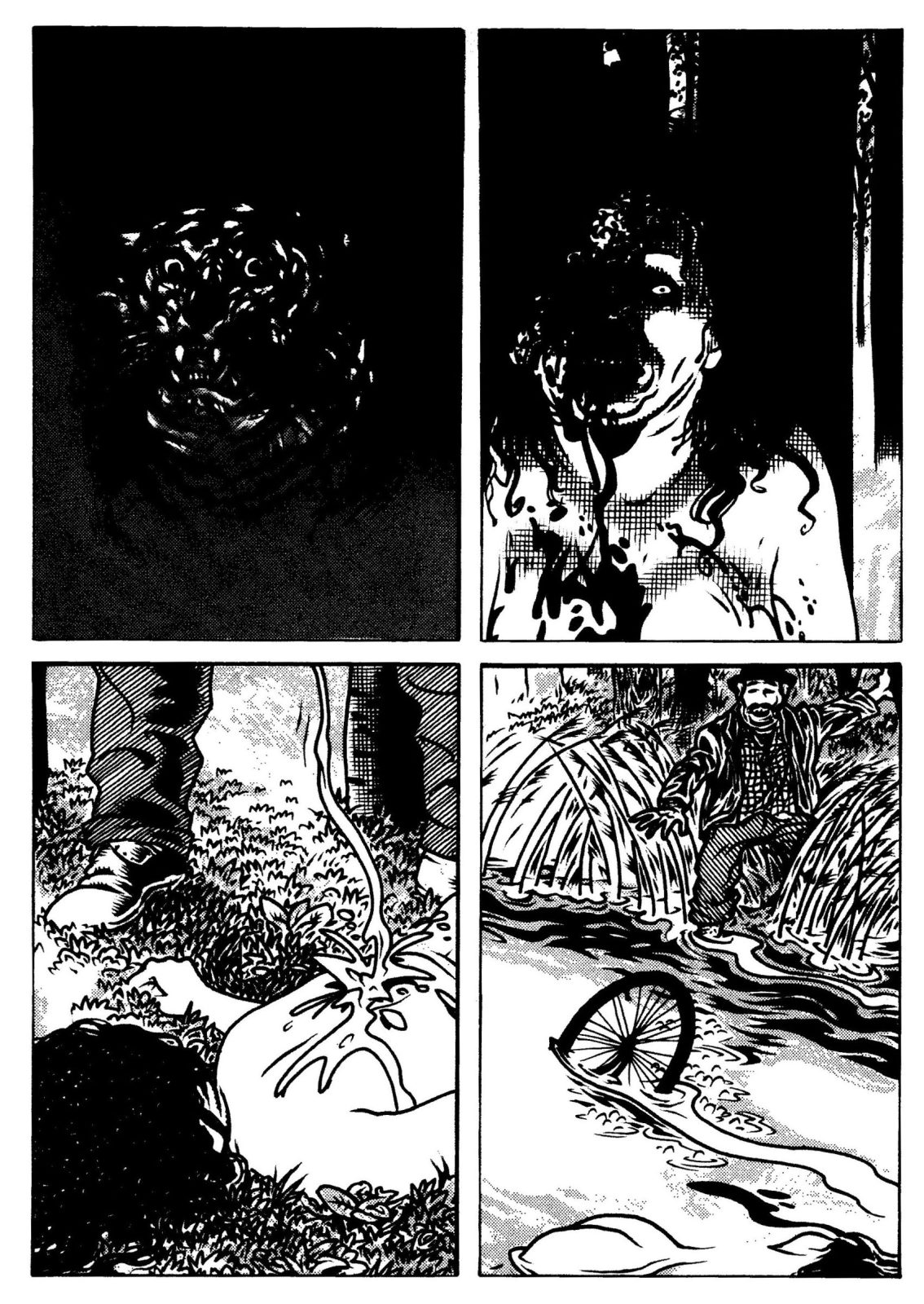

Beneath its cover—which, to be fair, looks a bit old-fashioned in its graphic design—the book opens with a dedication: A mia madre e a mia sorella, “To my mother and my sister.” Then, there is a sequence of four highly disturbing four-panel pages - stark black & white images, with a sickening halftone screen.

Page one. Panel one: bikes abandoned in the woods. Panel two: a naked woman, shown from behind, just a glimpse of her grotesque smile. Panel three: a man looking at her from behind a tree, drooling. Panel four: the woman leans down on all fours, buttocks facing the camera, legs parted, as if inviting the man and the reader to join in; a shadow seems to be approaching.

Page two. Panel one: the man’s face is contorted, his crooked teeth dominate an unshaved chin, his erect and pulsating prick emerging from a cliché peasant's checkered shirt. Panel two: another man wanders in the woods. Panel three: the new man spies on what’s happening from behind a tree. Panel four: a scream issues from behind the woman, still on all fours, looking back at her companion, who’s inferred to be penetrating her from behind; her face is a grotesque mask, without joy or pleasure.

Page three. Panel one: a deer emerges from a white background; elegant, beautiful, maybe scared, like a dream or a symbolic apparition. Panel two: the man is in front of the woman, his dick all that is visible to the reader; Apri la bocca, he says, “Open your mouth,” as she looks at him sweaty and desirous, though Corona draws her with no particular erotic aesthetic. Panel three: the new man is still lurking behind a tree, watching as the first man raises a club above his head while the woman kneels before him. Panel four: the first man grunts in pleasure or hate, his face distorted to an animalistic character, weapon raised.

Page four. Panel one: another symbol, a tiger, emerges from deep darkness, its muzzle mimicking the expression of the tumescent man. Two: the woman has half her face obliterated from the blow of the club; strangely, what remains of her face also mimics the appearance of the tiger. Panels three and four: the attacker pisses on the cadaver, now laying facing down, and then flees the scene, the corpse deposited in a river.

This introduction doesn’t tell you anything about what kind of story you’re about to read, aside from maybe hinting at a setting (some kind of rural area in the Italian province, maybe around the turn of the 20th century) and at a basic plot device (a brutal murder in the woods, with a body, a murderer, and a witness). But boy does it set the tone right away!

The aesthetic of the book is masterfully disturbing, even disgusting at times - there are close-ups of decomposing things, grotesque faces on caricatural bodies, maggots, vaginas, maggots inside vaginas, inscrutable secret agents, and all sorts of less-than-pleasing characters. Corona’s drawing style, at this point, is often said to be influenced by Robert Crumb's and Andrea Pazienza's most extreme and underground works. I would add Charles Burns to that list - the resonance between some of the more bodily aspects of Bestiario padano and Black Hole is staggering. But stepping outside of comics history, it’s hard to look at Corona's early works and not think to the early 1900s painter Antonio Ligabue, especially his self-portraits. There’s this unapologetic vibe in the depiction of bodies and their facial traits…

From my description, one could think of Bestiario padano as a depiction of rural life, and not a particularly flattering one. To be honest, up until a certain point in the book, it might well be just that: retrograde morals; distorted faces burnt by working the fields under the sun, teeth crooked from poor nutrition and poorer dental care; the stillness of Sunday afternoon wines at the local tavern; the contrast between outward righteousness derived from a mix of Catholic and pagan traditions, and inward lewdness and decadence. But then aliens start to appear, and people turn into centipedes, and vaginas form on the side of buildings, and deformed creatures arrive on the river via boat…

Now another emotion starts to build in the reader - growing slowly at first, then suddenly all at once to the point of becoming unbearable, surpassing the distress generated by the earlier portions of the book: a crippling sense of paranoia. What becomes evident in the second half of Bestiario padano–but is present from the beginning, in retrospect–is characters looking directly at you, the reader. Ligabue's self-portraits were usually frontal, but his eyes shift away from the observer, as if avoiding their gaze. With Corona, these strange peasants are looking at you, precisely at you, and there’s nowhere to hide because they follow you with their disgusting stare and their grotesque faces and bodies you cannot trust because they could be aliens or myriapods or whatever else. Few books make me want to run away like this one.

* * *

I think the best way to continue now is to jump ahead–way ahead–to a very difficult book titled Benemerenze di Satana (Hollow Press, available in Italian or translated to English by Valerio Stivè under the title “Satana’s Merits”). This comic was years in the making, finally wrapped and collected in 2018, but its genesis dates back long before Corona’s birth. Benemerenze di Satana is both an adaptation and a homage to the homonymous autobiographical work of mostly-unknown Italian author Domenico Vaiti, born in Messina in 1896; nobody knows when he died, but he is almost certainly dead. It’s a sort of diary, but the diary of a deeply disturbed person - I don’t use the term “disturbed” lightly, and I don’t mean to be offensive, but in all honesty I can’t think of a more suitable word. The protagonist goes on and on and on and on about his sexual obsessions; about the angelic (but more often demonic) voices he hears; about the trauma he suffered at the hands of a skinny prostitute, and his subsequent fixation with overweight women; about the haunting memory of kicking a skull for laughs in a time of war; about his allegiance with fascists first, and with communists later. But mainly his sexual obsessions.

It's a very difficult book to process, and definitely not a pleasant read - at least, not strictly speaking. Corona's visual style is all over the place: elegant hatchings giving way to blunter Ecoline inks or watercolors. Disturbing representations of the protagonist’s visions and sexual encounters alternate with walls of text: frenzied streams of consciousness from a not-so-sane mind. Taking a trip inside Benemerenze and expecting it to simply “make sense” in a rational, traditionally narrative way, is nonsensical. Navigating this emotional portrait requires the reader to abandon themselves to its seemingly disconnected ramblings; to accept brutal depictions of sexual desire–simultaneously self-deprecating and demeaning of women–with actual representations of a mental illness so acute it may as well be the divine (or malicious) calling the protagonist thinks it is... all communicated through an over-the-top, ever-changing, but constantly disturbing mix of drawing styles.

I don’t think I have ever read anything quite like it. And yet, despite the variety in Corona’s work I mentioned before, in reading Benemerenze di Satana you can feel it connecting to his other works. The growing sense of unease and paranoia, the brutal and sometimes blasphemous depiction of sexual acts, brings back to mind Bestiario padano. Indeed, the cover to Benemerenze depicts a huge woman on all fours, ass almost facing the reader, in a manner reminiscent of the second panel on the first page of Bestiario. Two major differences, though: here the aesthetic intent is clear, the woman's expression not a grotesque smirk but showing a hint of distant haughtiness; the protagonist is not going towards the woman, the object of his carnal desires, but is walking away, almost mortified.

I don’t think I have ever read anything quite like it. And yet, despite the variety in Corona’s work I mentioned before, in reading Benemerenze di Satana you can feel it connecting to his other works. The growing sense of unease and paranoia, the brutal and sometimes blasphemous depiction of sexual acts, brings back to mind Bestiario padano. Indeed, the cover to Benemerenze depicts a huge woman on all fours, ass almost facing the reader, in a manner reminiscent of the second panel on the first page of Bestiario. Two major differences, though: here the aesthetic intent is clear, the woman's expression not a grotesque smirk but showing a hint of distant haughtiness; the protagonist is not going towards the woman, the object of his carnal desires, but is walking away, almost mortified.

What we’re about to experience, the cover seems to say, is not a violent act towards the woman; the balance of power is completely reversed. Then again, exploring the book, this power balance is more complicated: without a doubt, the protagonist sees himself as a victim of these women and their beauty, while in fact, if he’s a victim at all, it is of his own obsessions - trauma and uncontrollable desire. Moreover, the protagonist’s fetish for self-deprecation and submission, together with his self-proclaimed hermaphroditism (in this sense, a man who possesses feminine characteristics), blurs the distinction between victim and oppressor in a challenging way: the women Domenico yearns to be dominated by are almost prehistoric examples of exaggerated femininity, with huge bosoms and huger hips. But he also sees himself as a woman - or at least partly one. So, symbolically, who’s dominating who? If in Bestiario the power balance is clear–male/murderer on one side and female/victim on the other–who’s on top of the food chain here? Who is Domenico Vaiti, and what role does he play - or what role does he think he plays, in his narration of his own life?

The book ends with Marco Corona himself becoming a character on the page and giving up on his adaptation. “When I get tired of Vaiti," Stivè translates, "I take my scooter and go for a ride around Roma.” But Vaiti's visions still permeate Corona's world. On the last page, the walls sprout eyes and faces that follow Corona while a Junoesque woman, one that may as well have been the object/subject of Domenico’s obsessions, addresses him directly: “Don't forget to change the oil!”

* * *

By that point, it was not new for Corona to blend his own life into his works. For instance, his first book was deeply informed by his personal experiences, despite it being a biography of Frida Kahlo. It originally came out in 1998, titled Frida Kahlo - Una biografia surreale (Stampa Alternativa, 1998; then Black Velvet, 2006), which translates to “Frida Kahlo - A Surreal Biography”... and surreal it is! More a collection of moments than a monolithic or chronological recollection of life events, with a fragmented style of narration that closely resembles the later erratic nature of Benemerenze, it’s a very nice portrait of not of the artist’s life, but of her essence, as seen through Corona's personal attachment to her. Years later, the author would revisit this very early work and complete it with a second part. The augmented book would then be titled Krazy Kahlo (001 Edizioni, 2016). The newer part of the book is basically a series of unmerciful splash pages depicting Kahlo's struggle with pain following her 1925 bus accident: a pain that would go on to become an intimate part of her life, as well as one of the main focuses (possibly the main focus) of her artistic pursuits. For our purposes, know that chronic pain appears to be something Corona shares with Kahlo (though I can only hope Marco’s is less dramatic in origin), which not only makes the representation of suffering more on-point and heartfelt, but tightens and deepens the connection between the two. In this way, Krazy Kahlo is both one of the best Frida Kahlo biographies (albeit a predominantly thematic one), together with Vanna Vinci’s, but also a more general consideration of pain and suffering, and the way it intertwines with artistic purposes.

Corona's other books are more upfront yet dismissive of their autobiographical nature. I’m thinking about La seconda volta che ho visto Roma (Rizzoli Lizard, 2013), which translates to “The Second Time I Saw Rome”. It’s a wonderful recollection of the author's journey to the capital - he went there hitchhiking to see the rock band Marlene Kuntz. But it’s also the story of the city itself, a complex book composed in an equally complex style, formed from symbolic connections and stream-like thoughts more than any argumentative historical reconstruction. Even more, I'm thinking of In mezzo, l’Atlantico (Coconino Press, 2005), “In Between, the Atlantic” - part autobiography and part travel diary of time the author spent with his girlfriend in Colombia, drawn in a style that both resembles and distances itself from Bestiario. It clearly is a personal recollection of real events, a window by which the reader may peek into the author’s past life. And yet, the book opens with a bold statement: “This is not an autobiographical story, maybe it’s not even a story, the same way its protagonists are not my girlfriend and me but two impostors that look a lot like us, like two drops of water. Colombia and Bogotá themselves aren’t real in this comic—for the only certain thing is that this is a comic—they’re nothing more than glimpses, papier-mâché sets, buildings and roads drawn with chalks. Everything is fake.” So, what’s real? Marco’s experiences in Bogotá with his soon-to-be wife? Domenico Vaiti's struggles with divine intrusion into his mind, and with his own sexuality and obsessions? Is Corona himself giving up on making sense of Vaiti’s work in Benemerenze di Satana even real?

* * *

Reading over this piece, I feel like Benemerenze is starting to look a lot like the centerpiece of Corona’s body of work, and in a way it is: it functions as a showcase of the artist’s proficiency and experimentalism in various drawing styles - and, above all, of the erratic, confusing, and at times unpleasant nature of his narratives. It’s all of these things, for sure, but at the same time I think we should now approach what I see as the true cornerstone. The key to it all, in all its apparently random peregrinations. I’ll jump right into it.

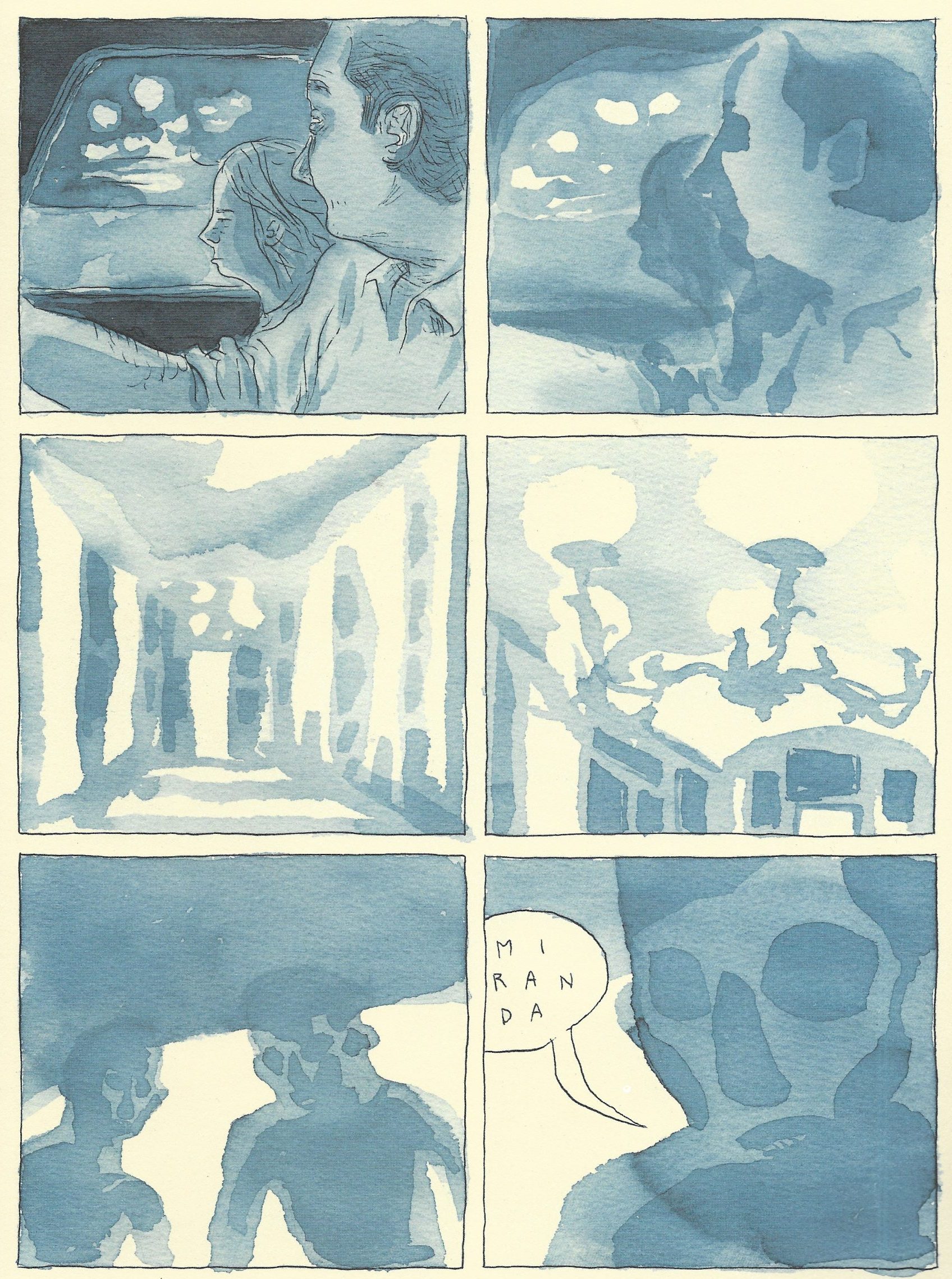

Riflessi (translated to English by Kim Thompson under the title "Reflections") was published in 2006 and 2007 in three chapters, as part of Coconino’s Ignatz series: a line of A4-sized deluxe stapled comics, made available in North America and the UK in collaboration with Fantagraphics. Editorially, this is very different from Coconino's reputation in Italy as the “main” graphic novel publisher. The Ignatz series published some of the most important international cartoonists of all time - Gilbert Hernandez, David B., Richard Sala and Kevin Huizenga, but also the Italians Sergio Ponchione, Leila Marzocchi, Gabriella Giandelli, Igort himself, and Gipi. And then, in issues 11, 14 and 17 of the series (10, 18 and 24 in the English series), there was Marco Corona with Riflessi, 96 pages - his masterpiece.

Everything starts with a dream, Miranda’s dream. Miranda is a small girl spending the summer with her grandmother because her brother is sick, hospitalized near the sea. In her dreams, she foresees her future: a bright palace with a translucent crystal chandelier and 365 rooms, one for each day of the year, though some are closed because of water seepage. Her mother is "crazy," she says.

Then Miranda is old. She lives alone with a lot of cats, which were prohibited inside the house when her parents were alive. Her brother got well, and now spends all his time traveling. He sends her postcards from around the world.

Suddenly, we’re back by the shore. Kid Miranda goes to visit Riccardo, her brother. Their father never visits. Riccardo daydreams of being the captain of a pirate ship.

Miranda is a little bit older. She sneaks out of the grandmother’s house to smoke; a boy named Topo (which means “Mouse”) always offers her a cigarette beneath the underpass separating the house from the sea. She barely knows him; they never speak, they have nothing to say to each other, and she never says thank you. But one night, something goes wrong, and the boy attacks her beneath the underpass. She manages to escape, and never speaks about the incident with her family.

Riccardo is the fearless captain of a pirate crew. Some days earlier, they assaulted another ship and set it ablaze. Only two were spared: his father, the rival captain, forever condemned to exile; and Miranda, because “we need a cabin boy!” At one point, Riccardo shoots somebody on deck while down below a member of the crew named Topo attacks Miranda, who stabs him in the eye, so that he has to wear an eyepatch. Miranda is washing herself. “You don't want to carry the rat's offspring,” somebody tells her. But then Riccardo tricks his own crew into disembarking from the ship. He sails away, wandering, as he’s doing now, in real life, so many years later.

Again, the underpass. The boy Topo, who always gives Miranda cigarettes, rapes her with two accomplices. She reaches for something metallic and pointy and stabs him.

Miranda is a small girl. She pictures her future as a bright palace with a translucent crystal chandelier and 365 rooms. She’s visiting the palace, which is now a museum, with her crazy mother. When the tour is over, she discovers the exit is the same as the entrance. We’re back in the present, which is also Riccardo’s fantasy of piracy, and his escape from the crew after casting away his absent father, and Miranda’s rape, and her visits to grandma and the hospital by the seashore, and her smoking in secret, and her life with cats. “Everything starts somewhere,” are the closing words of Riflessi, and yet everything has already happened. And keeps happening, echoing through the walls of an empty palace, or reverberating through the everchanging reflections of a mirror.

It’s a stunning series. Maybe less brazenly disturbing than Bestiario padano or Benemerenze di Satana, but no less potent. On the contrary, it’s poetic and delicate, emotional and symbolic in a way that makes you want to cry, even though you may not realize why. A great representation of trauma - the one thing that touches and influences every other thing. Because of this, the narrative is not linear; time goes back and forth, and reality blends with dreams and hopes and reveries, because trauma isn’t rational. There’s the moment itself, and its aftermath, but time is shaken so that all the moments before the event are just moments leading to and from it, which determines your imagination and dreams. Everything overlaps; the exit is the same as the entrance, and all has yet to happen despite having already happened. At the same time, there’s a room for each day, even though some are unusable.

If Benemerenze is a showcase of Corona’s technical skills, and his way of frantically building stories, Riflessi depicts better than anything else how the collection of fragments that composes his stories all fit together to form the emotional portrait of a state of being.

Looking back at Marco Corona’s works, I struggled a lot to find a fil rouge uniting them all. I meant to compose a systematic and chronological analysis of his work, to examine both his stylistic and poetic evolution over time, to find a common theme amidst the variety. Then I thought of Riflessi - of it being the story of Miranda and Riccardo, but also, probably mainly, the portrait of trauma. The same way Krazy Kahlo is a portrait of pain and suffering, Benemerenze of sexual obsessions, Bestiario of paranoia, In mezzo, l’Atlantico of that kind of nostalgia that makes the past real and imagined at once. The same way his series L’ombra di Walt (Coconino Press, 2008-2009) is unfinished, and therefore a perfect depiction of depression; Il viaggio (Eris Edizioni, 2021) a dreamlike exploration of childish and childlike terrors; La galaverna (001 Edizioni, 2018) a journey through grief.

And so it struck me. Maybe Marco Corona is not trying to tell stories - not in the prosaic sense. Maybe he’s trying to capture emotional states of being: traumatized; obsessed; paranoid; depressed; nostalgic; suffering. States of being are atemporal in his stories; they don’t need chronology to work, they refuse causality and rationality and linearity. So I decided that was the aspect of Corona’s work I wanted to try and convey, jumping around through his books as he does in the stories they contain. Building sense from seemingly unrelated fragments. Because, in the end, as Riflessi so plainly states, all has yet to happen, and yet everything already has.