Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie is the most misunderstood and misinterpreted comic strip of its era. It was never easy to classify; it changed as its creator’s skillset grew. Gray’s Depression-era narratives are powerful depictions of the hard-scrabble life much of America endured. This is the Annie that inspired the stage play and film of that name—the gutsy, outspoken girl and her ever-arfing companion, Sandy, risin’ through adversity th’ ‘Merican way. (The contemporary radio version of Annie owes much to this incarnation. She and Sandy moved a lot of product for their sponsor, Ovaltine.)

Elements of World War II crept into the strip by the end of the 1930s. Axel, a sinister espionage master and would-be tyrant, hounded Annie and Warbucks well before America entered the global fray. The wartime Annie is perhaps the least interesting stretch of the strip. Though Gray relaxed his extremist political views and expressed grudging (and temporary) admiration for Franklin Delano Roosevelt, he seemed to create the sequences in which Annie forms a Junior Commando squad and tackles hometown hoarders and black marketeers with more a sense of duty than inspiration.

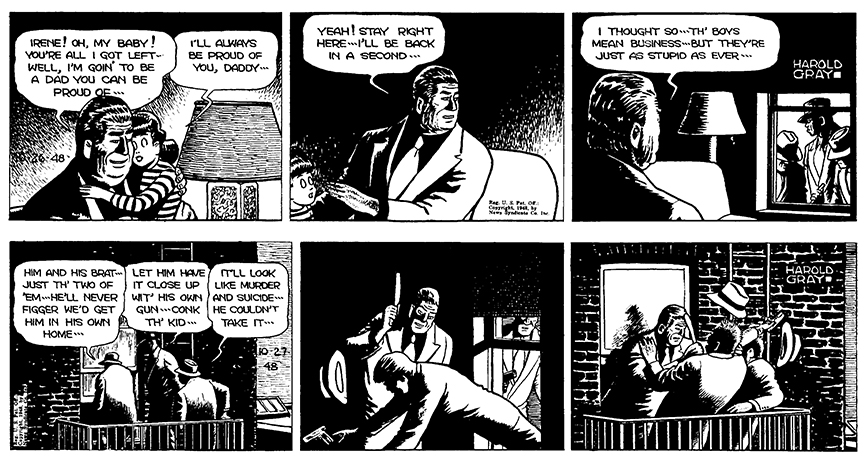

Though Gray eschewed the gritty, brutal combat scenarios that Roy Crane depicted with grim power in Buz Sawyer, some of the nightmarish sense of wartime flavored his domestic melodramas. That fatalism—which emerged in contemporary American films and novels—would soon be known as noir, a phrase the average person recognizes today. It is fascinating to see the noir sensibility take hold in Gray’s work after 1943.

And though Annie was still given to philosophical soliloquies that couched her creator’s political biases, that luck-and-pluck, sun’ll-come-out-tomorrow character of the radio show and musical didn’t exist by WWII's end. The strip continued its typical course. In the infrequent company of her benefactor, Oliver “Daddy” Warbucks, Annie has short spells of well-being. Warbucks leaves the picture, due to business matters or mayhem, and Annie is forced to fend for herself. She and her russet dog, Sandy, hit the road in search of safe harbor. She typically wanders into a small town, where a benevolent couple—or a brutal malefactor—takes her in. Annie exposes hypocrisy, razzes the status quo and gets herself into peril. She is trapped in a bad situation—a vicious orphanage, the home of a sociopathic sponsor—and sticks it out until there’s nothing to do but run. There is always a new town, new friends and enemies to meet, and her lot is seldom dull.

When alone—engaged in vague chores or walking with Sandy—Annie pontificates about people, politics, justice and the inherent ironies of life. She speaks for her creator in these moments. Her creator had a lot to say, and his strip was a daily pulpit for his gripes and hopes. Some of his views remain hysterically cracked. Others seem almost liberal compared to 21st-century conservative and reactionary schools of thought (and I use the term loosely). I'll leave it to you to discover these moments, and see where they fall on your sociopolitical spectrum. Few comic strip creators so blatantly wove their personal agenda into their work. Make of it what you will.

Annie was equally controversial for its intense moments of menace, doom and violence. As a raconteur, Gray has few equals in his field. His story cycles merge, morph and melt away in layers. Events and characters from past episodes return to haunt Annie and her friends. At any moment, Annie’s world is turned asunder by the arrival of a pal or a bitter enemy. Like Charles Dickens, whom Gray admired, fortune and misfortune take a masterful shuffle through the lives of his characters in his narratives. The pleasure of reading these stories exacts a price of the reader.

Each time I begin a new volume of The Library of American Comics’ Annie reprints, although I know it’s coming, and try to be prepared, the first incident of Gray’s soapbox screeds is jarring. His views, mild or emphatic, are blunt, and intended to shame those who have transgressed. In Gray’s eyes, that is almost everyone. Virtue is more precious than gold in Annie’s world. Redemption is possible, after much suffering, though the occasional ne’er-do-well is tolerated, if not applauded. For every rule in Gray’s worldview, there are myriad exceptions. His harsh and self-conflicted opinions are the portal a reader must pass through to enjoy his storytelling. Once I’m inside Gray’s world, I get lost in his teeming narratives—stories that become weirder as the war ends.

In the mid-1940s, Gray seems newly inspired and more willing to take risks. The turning point occurs in late August 1944, when Annie, having witnessed the watery underground death of a nest of fifth columnists, and her ailing benefactor Warbucks’ apparent death, falls into the hands of Mrs. Bleating-Hart. Her new home is a prison; Annie is worked from dawn to dusk and must endure Bleating-Hart’s constant stream of condescending criticism. (Her pontifications chafe as much as Gray's—an irony that was unintended.) This socially admired woman, who resembles Eleanor Roosevelt and is considered a do-gooder, hides a black heart under her genteel exterior.

This long narrative is as noir as American comics got in the 1940s, with a murder sequence worthy of James M. Cain and moments of unremitting bleakness. This blend of Victorian melodrama and hard-boiled crime, tempered by the home-front tensions of wartime, continues well into 1946, as Annie is tried in court for the murder of Mrs. Bleating-Hart.

This storyline, in volumes 11 and 12 of the LoAC’s series, is among the great comics narratives of its decade. Its sense of entrapment and inescapable doom is horrifying. It's Victorian gaslight melodrama with a jitterbug twist. Here, Gray wipes the slate clean. With the war over, the strip could be about anything, take place anywhere. Though controversial—Jeet Heer’s excellent introductions in the Library of American Comics books report a stream of complaints from readers and editors—Little Orphan Annie remained popular and beloved. With Dick Tracy, Terry and the Pirates and Gasoline Alley, all Tribune properties, it was an asset to any paper that could run it.

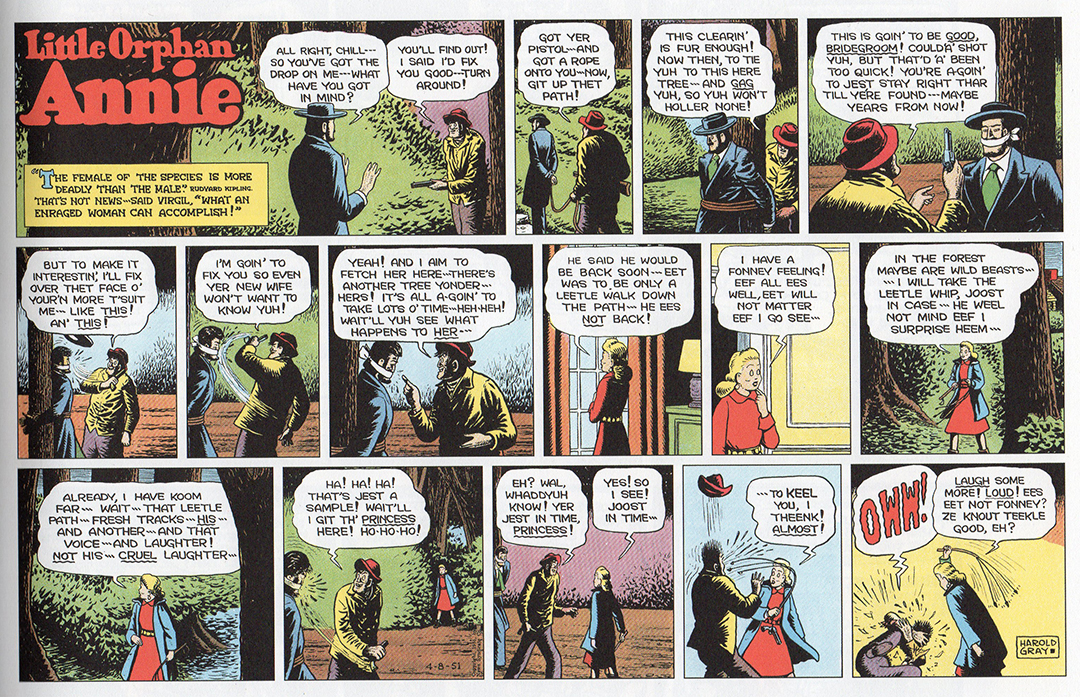

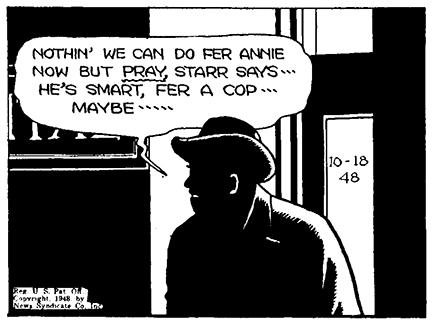

During the war, fundamental visual changes came to Gray’s strip. In the 1920s and ‘30s, it was, in daily and Sunday installments, a relentless grid. Every weekday strip had four equal panels. Sunday strips adhered to a rigid layout that stacked as a full-page or tabloid (portrait) or half-page (landscape). As with Dick Tracy, this grid imparted a hard rhythm to Gray’s strip. Here are two examples: the classic grid of the 1930s and the experimental post-war style.

By war’s end, the daily was reduced to three panels. The Sunday strip, a rigid layout up to 1945, experimented with varying panel sizes—from Bernard Krigstein-style slivers to panoramas. This easing of rigor, along with a simplified, stark chiaroscuro approach, makes the post-war Annie one of the most visually striking comic strips of its day.

Gray’s strip began in a flat simple style typical of the mid-1920s, and became more expressive by decade’s end, with complex pen-and-ink shading and cross-hatching. The 1930s saw this approach reach an atmospheric peak. This decade’s strips often achieve a deep mood of mystery, melancholy and a sort of visual poetry. They are a counterpart to French films of the decade like Marcel Carne’s Daybreak and Port of Shadows and Jean Renoir’s La Bēte Humaine, Grand Illusion and La Chienne. (The finest film equivalent to Gray’s atmosphere is Charles Laughton’s 1955 The Night of the Hunter, which nails the mood of the late ‘30s Annie.) The visual elegance Gray achieved served his increasingly dark and enigmatic storytelling whims.

After the war, this style hardened to a powerful shadowy black and white that suggests the work of cinematographer John Alton, one of the visual architects of American film noir, which drew inspiration from the European films of the ‘30s. Gray arguably did this technique better than Milton Caniff or Chester Gould, though the three cartoonists have different approaches to their work. Gray could create striking compositions in pure black and white, with a minimum of linework and an absence of cross-hatching, as seen in these strips from 1948:

The 14th volume of LoAC’s Annie series might be a safe bet for new readers. Though it starts and ends in mid-story, it mines some of Gray’s richest themes and greatest eccentricities. It contains a brief pro-comics narrative, which is played up big on the book’s dust jacket but barely has a chance to happen. For a month at the start of 1949, Gray let the censorial critics of comics have it with both barrels. Annie refers to these early social justice warriors as “Hitler helpers,” and the story climaxes with a book burning that claims the small town’s library. Perhaps Gray was told to stop this storyline. In its brief run, if often fades into the background as more mundane events take center stage.

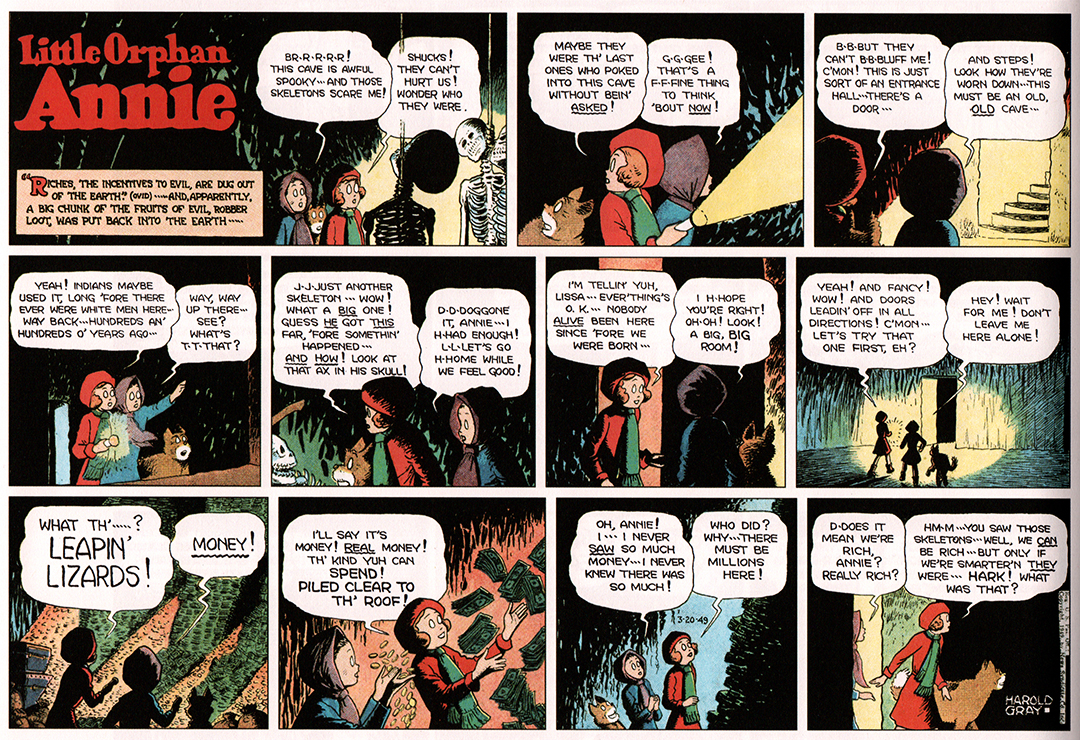

This controversial narrative thread is brushed out of the way for one of Gray’s grandest and least logic-driven storylines. Recapping narratives of Annie does the work no favors. Events that sound bonkers in synopses come alive when read and absorbed. In this sequence, which spans February to July of 1949, Annie becomes a curious fantasy dressed in street clothes. Relocated to a bleak farm hamlet, Annie and an ailing friend are taken in by Jeb and Flossy Jitters, rural under-achievers whom are transformed by Annie’s no-nonsense work ‘n’ win attitude.

Annie is intrigued by a bleak rock quarry near the Jitters’ farmhouse. In its dismal valley is a run-down cottage inhabited by Gypsy Belle, a cackling loner the townsfolk call a witch. With her tangle of long brown hair and Shakespearian dialogue, Belle is tuned into a different wavelength than her neighbors. Annie befriends her and learns of a vast treasure left by generations of criminals that is concealed within the towering walls of rock.

What happens next suggests a merger of a Frank Capra movie and One Thousand and One Nights, the classic collection of Middle Eastern myths and legends. It's a striking, baffling blend of themes and treatments. But disbelief gives way to absorption. Harold Gray sells us a load of hogwash and has us hooked. Gypsy Belle entrusts Annie with a magic whistle that, when tootled right, opens a mystic door to this horde of plundered wealth. Sent for her assistance is Funjab, a pint-sized cousin of Punjab who is more prone to pranks and play than Biblical justice.

Annie intends to do good with this money, which she considers hers by the homespun rules of “finders keepers.” She begins work on a Utopian town for orphans—the safe harbor she has never known for long. Then the government steps in and seizes the wealth. Officials attempt coerce her to blow the whistle and give them access to the subterranean mounds of gold, jewels and currency. She refuses; they attempt to blast the vault open, but the explosion swallows up this mega-fortune and it is lost for the ages.

This wasn’t Gray’s first incursion into the supernatural. The godlike Mr. Am, introduced in 1938, and Warbucks’ right-hand men the mystic Punjab and the murderous, cadaverous Asp are larger than life, have supernatural abilities that are never coherently explained. They appear at opportune moments to extract Annie from death and destruction. In a fall 1946 narrative, Annie discovers that she can communicate with ghosts. These spectral agents of mirth and mischief help her torment a group of gangsters who have threatened Annie’s life.

Sans ghosts, Annie’s associates walk in other worlds. Punjab, a towering Indian mystic, sends malefactors to another dimension with the aid of a magic cloak. Warbucks chuckles at this gruesome parlor trick, and Punjab makes it clear, through measured language, that these travelers have met a nightmarish doom. Shades of Fletcher Hanks and The Spectre!

Such moments in LOA are presented at face value and street level; they just are. With these paranormal forays, Harold Gray explored a personal deep end which has some equivalents in comics, but none quite as peculiar and inexplicable.

Gray’s narratives are structured like classic fairy tales, and evoke Little Red Riding Hood, Hansel and Gretel and Snow White as they recall Charles Dickens or Victor Hugo. Annie often falls into the hands of people and institutions that wish her physical and emotional harm. As with Mrs. Bleating-Hart, whose demise is worthy of the Brothers Grimm, the villains in Annie meet dramatic, sometimes poetic ends, and our heroine and companion canine live on, none the worse for their misadventures.

Gray never seems to write for children—that is, to aim down to their assumed level. These mystic shenanigans play alongside hard-bitten noir and rural tragicomedy. The inexplicable hovers at street level at the heart of Gray’s work. Call it magic realism before its time. No other comic strip worked this corner of the universe with success. Those who write Annie off as hawkish propaganda, or sentimental kid stuff, haven’t spent time with the strip. Yes, melodramatic elements are there; yes, characters utter sweeping statements about society and politics that may cause modern blue-state readers to blanch. Gray’s dogmatic views and playful leanings are components of a sprawling and often-unguessable game of storytelling.

The remainder of LOA 14 occurs in a marshy underworld that explicitly recalls French film of the late 1930s. Annie rescues a dying woman who has been abandoned by her no-good ex-con husband. With Annie’s pre-programmed pluck in her corner, sickly Lena gets back on her feet. With the help of a community of friends who live in this brackish fen, Annie converts Lena’s houseboat into a seafood restaurant. Its success gives way to noir tension and tragedy.

The pregnant atmosphere of the swampy setting inspires some of Gray’s most striking night-time and outdoor scenes. Like the craggy rocks of the quarry, the towering reeds that choke the swamp are claustrophobic, as befits the story, and give their artist dynamite geometry to compose stunning chiaroscuro panels. After the epic daffiness of the quarry narrative, this stretch of Annie reminds us that Gray’s feet are on the ground, be it marsh or macadam.

Gray wasn’t through with the jutting imagery of the rock quarry, vast treasure caches nor the presence of the paranormal. In the summer of 1950, these themes return. Sequences in the 15th volume of Annie renew an anti-Communist streak in Gray’s work. Gray’s hatred of dictators and controlling governments never abated, and sinister agents of what we presume are Communist countries appear in the strip prior to World War II. The Cold War environment brought global focus to Soviet Russia and its leader Joseph Stalin. This was prime material for Gray’s radar, and his anti-Communist view gained new vigor from 1950 on. These narratives are fascinating and promise a rich decade to come for the reprint series.

The post-1944 Annie has never been reprinted; the last comic-book reprints of the strip appeared in 1948 and contain material from 1940 and 1944. It’s possible that the political content of the post-war strip made it too hot a potato for comic books. Other strips from the same syndicate—Dick Tracy and George Wunder’s Terry and the Pirates—continued to be rerun in comic book form into the era of the Comics Code.

Prior to this sequence, “Daddy” Warbucks is present for a long spell. For once, this isn’t a time of tranquility; Communist spies attempt to destroy Warbucks, the symbol of decadent Western capitalism. With Punjab and The Asp’s superhuman help, Annie and Warbucks escape death. Warbucks spirits Annie to the Western ghost-town of Fiasco, where his old friends Lightnin’ Lem and Sarah live in isolation. As one might expect, Warbucks soon disappears—the apparent victim of foul play—and Annie is in the benevolent hands of old family friends.

Lightnin’ Lem's search for the fabled “Lost Armenian” gold mine has cost him 40 fruitless years—until a landslide reveals the long-obscured aperture to the cache of wealth. With this opening comes Annie’s next contact with the netherworld—and another moment that stretches our suspension of disbelief to its extremes. A Western-accented ghost who calls himself “Windy” addresses Annie and Sandy, who seek help for the dying, injured Lem. “Windy” explains his presence to Annie in words worthy of a fairy tale:

You have th’ special powah, Mam, possessed by only th’ pure in speerit…

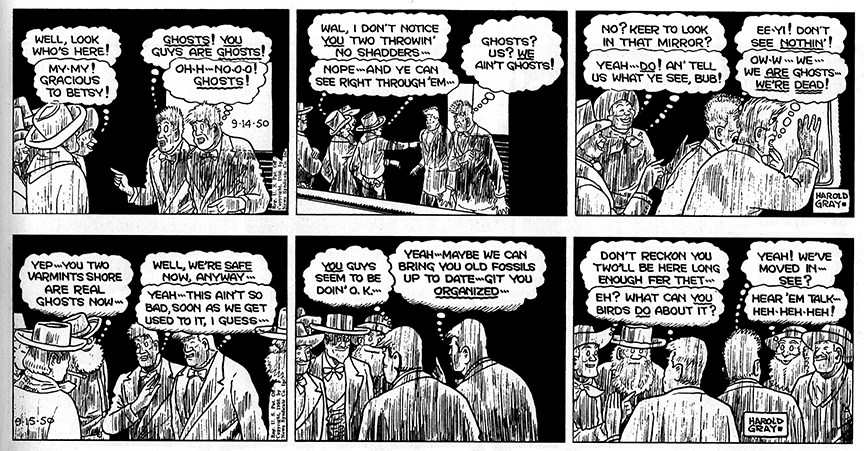

“Windy” introduces Annie to other gold-rush specters. As with the 1946 sequence, Gray plays his ghostly cast for comedy. In the strip for 9/14/50, a group of ghosts welcome two gangsters-turned-spirits to the fold. They must be convinced, by their lack of reflections in a convenient mirror, that they’re dead:

Lem and Sarah are hornswoggled by the ghostly antics, but they proudly display the status symbols of wealth in Gray’s world—fancy clothes, diamond stickpins, spats, cigars and pearls.

This sequence, and its earlier kin, provide a litmus test for your Annie tolerance. You either buy into Gray’s cracked wonders—sidestep the political rants and get sucked into his fevered storytelling—or you don’t. Like Chester Gould, Gray was an eccentric yarn-spinner with a popular public forum. Newspapers jockeyed to get the rights to Little Orphan Annie and Dick Tracy. The strips were proven circulation builders and got the primo spot on a paper’s daily and Sunday comics pages. This was not outsider art, nor arcana—it was as mainstream as it got. Millions read and followed this work.

If readers carped at Gray’s political views—which, in the age of Trump, seem mild-mannered—they didn’t dare miss an episode. Annie remained a top strip through the dawn of the Space Age; only Gray’s diminished energy, as the 1960s rolled on, slowed its unconventional pace. (Gray died of cancer in 1968; the strip continued in a miserable state by various hands. It expired in 1974 and reprints of late 1930s stories began.)

The visuals of Annie also confound expectations. The outer face of Gray’s cartooning is primitive. The empty orbs of his characters’ eyes, the crude blurs of their facial features and exaggerated proportions seem less ‘real’ than the angular figures of Gould, or the slick but crude cast of Zack Mosely’s aviation strip Smilin’ Jack. Gray’s skill as an artist belies the false front of his human characters.

He may have been comics’ greatest landscape artist. Obsessed with texture, he renders wood, stone, gravel, brickwork and dirt with a gravity and striking sense of design. In these two quarry-set sequences, one feels that Gray’s interest lies in the dynamics of landscape; the characters are an interruption to these haunting vistas of wear-streaked stone, stark light and shadow and the powerful shapes of nature. These three 1950s strips are breath-taking:

The Sunday episodes showcase another Gray eccentricity. His sense of color is out-there. As distinct a signature as the “Hark!”s his characters utter every few strips, Gray’s pastel palette bursts with baby blue, pale yellow, moss green, sherbet orange, pink and violet—applied to objects that are never those hues. He changes the colors of objects and settings, from panel to panel, in “real” time as characters converse. Shrubbery is yellow in one frame; pink in the next; violet in the last. The range of these colors is gentle, but their constant clash adds to Annie’s irreal impact.

Harold Gray’s work of the late 1940s and early ‘50s, created in his 50s, is an example of what popular culture tries not to be, in the 21st century—made by middle-aged, eccentric Caucasian males, and targeted to no clear demographic. America’s cultural horizons have broadened much since Gray’s heyday, but these old white guys raised hell on the comics pages, were paid handsomely for their effort and became celebrities. They were careerists, dedicated to one, perhaps two, features for their professional life.

With the works of Gray, Gould, Caniff, Frank King, Roy Crane and other long-term comic strip creators at our fingertips, we now appreciate their peculiarities of style and approach and the extent to which their personalities informed the work. Only death or exhaustion took them away from a life’s work, created in endless rows of panels, borders, speech balloons and blunt, powerful images. Newspaper comics have no pull, no agency, and may cease to exist in the next decade. We are fortunate to have these huge bodies of work preserved. Comics have lost most of this mid-century, mainstream American crazy. The world moves on, and the market, audience and atmosphere for such work may never exist again.