Collecting and studying Trevor Von Eeden’s work back in the day wasn’t enough for me. I looked everywhere, seeking any information on him. Zero luck. If no one was going to interview him, I thought, I’ll do it myself. After trying and failing to get ahold of him, no thanks to a string of tight-lipped industry people, I struck gold early 2008. We hit it off, but not knowing what to expect, I gave Trevor interview options, wanting to make it as comfortable for him as possible. He agreed to a written Q&A — I was too green to insist on a spoken interview, hence my overabundant questions, making sure I didn't miss a thing. I transcribed Trevor’s series of handwritten responses over the course of the year, and TCJ graciously agreed to run the piece. It was May 2009 by the time the interview saw print in issue 298. I've now been asked to rerun our back & forth over a decade after its debut, and I'm perfectly happy to oblige. The more Von Eeden coverage, the better. — MF, 7/26/19

From The Comics Journal No. 298, May 2009

From The Comics Journal No. 298, May 2009

An Interview with Trevor Von Eeden

Trevor Von Eeden stands as an unsung comic artist with a visual lexicon that mostly consists of sketchy yet clean Toth-like figures and complex storytelling solutions informed by an avant-garde level of design. He built a short but unforgettable framework in which he defied and pushed the norms of the mainstream American comicsphere, especially as co-creator of the genre-bending Thriller, one of DC Comics’ oddest, riskiest, and most sophisticated releases to date.

It was a mystery to me as to why he hadn’t produced much work in recent decades, especially when the platform was open to both creator-owned material and independent publishing. I looked everywhere for any shred of information not only about Von Eeden’s disappearance but about the artist himself.

The more I looked the less I found. No in-depth interviews with Von Eeden existed* and a very minimal Wikipedia entry was put up shortly before I began my search. My curiosity is not rooted only in appreciation but in confusion. With this embarrassing lack of documentation, the mystery deepened. How did such a raw and bizarre talent once thrive under the less than perfect circumstances of the mainstream comic book world of the 80s? Why did it oddly mutate in the face of the burgeoning yet exploitative industry of the 90s? Why have his contributions been obscured rather than archived? Instead of becoming the Next Big Thing after flexing the talent to back it up, Trevor Von Eeden’s comic output dwindled, his style changed, and he nearly fell off the face of the Earth.

I couldn’t chalk it up to yet another “comic industry kills creative spirit” scenario. Instead of hoping for a retrospective puff piece to appear in a fan magazine, I decided to go directly to the source. As it turns out, Trevor Von Eeden never really left comics; he was an anonymous, exhausted freelancer who could no longer commit to an apathetic, racist, and corrupt business.

Now, after years of working on a scattered backlog of comics, he’s focused on writing and drawing a 240-page web comic-to-graphic novel about the life of boxer Jack Johnson, the first black Heavyweight Champion of the world. Possibly Von Eeden’s most personal work to date, The Original Johnson promises to be an inspiring socio-political biography.

With the recent debut of his online comic at ComicMix.com and the interest surrounding his subject matter, Trevor Von Eeden is finally getting the recognition he deserves by way of mainstream media press coverage. Von Eeden’s reemergence, however, has been bittersweet due to a pending lawsuit over a broken contract and stolen artwork. To top it off, Von Eeden was described to The New York Times as “a very private person,” by ComicMix editor Mike Gold, who declined an interview to the Times on Von Eeden’s behalf without his knowledge or consent. The following interview is proof that Von Eeden has plenty to say about a lot of things including being the first black employee at DC Comics, the creation of Thriller, Lynn Varley, the ComicMix legal issues, and how he is far from being done with comics. The Original Johnson is an example of how Von Eeden may just yet expand upon his body of work on his own terms.

Many thanks to David Allen Jones for connecting me with Mr. Von Eeden in the first place and for being kind enough to offer me his knowledge and insight. His unofficial Thriller website was a fantastic starting point for this interview. A deep appreciation and respect must be given to Trevor Von Eeden himself for taking the time from his busy schedule to do this interview, which was conducted and copyedited through several letters and e-mails, and for his willingness to share his thoughts on all things comics, past, present, and future.

*Up until very recently, there were only 3 known articles on Trevor Von Eeden. The first was a short introductory editorial in Black Lightning #2, Von Eeden’s second published work circa May ’77. The next piece was an exclusive look into the debut of Thriller in the pages of now-defunct fanzine Amazing Heroes #30, Sept. ’83, which mostly focused on the co-creator of Thriller, Robert Loren Fleming. Fast forward 20 years and you get a retrospective piece in the pages of Back Issue #8, under Tony Isabella’s “Off My Chest” guest editorial. The Von Eeden interview revolved around the creation of the character Black Lightning and was conducted by Brian K. Morris.

MICHEL FIFFE: You broke into the comic book business at the age of 17 and co-created the character Black Lightning with Tony Isabella for DC Comics. How did that happen and how did you feel about this “dream job” at such a young age?

TREVOR VON EEDEN: My friend, Al Simonson, whom I’d met in junior high school in ’71, about a year or so after moving to America with my family (I’m from Guyana, South America), introduced me to American comic books. His collection was extensive, and his desire to share his love for comics with me, and his comics themselves, was infinite. Al was my first, best, and most influential critic/fan. If I did something that he liked, it pleased me tremendously.

Four years later, I’m 16. Al convinced me to send some ballpoint-pen samples to DC for a “professional” critique. I received a form letter in return. At the bottom, a handwritten note inviting me to drop by if I was “ever in the neighborhood.” The best thing about the Bronx is that it’s an hour away from Manhattan.

So an hour later … No, it took two hours — I had to take a shower, get dressed, work up the nerve! Actually, it was a few days later. First, I had to let the notion sink in that I’d really been invited to “drop by!!” I’m 16 at this point, remember! Anyhow, I dropped by. As soon as they saw that I was brown-skinned, I was ushered into Joe Orlando’s office.

He had to explain to me what he meant by “we have a ‘black’ book for you to do” (if I wanted the job, of course). I grew up in Guyana very happily, with other children of all colors. Racism was a foreign concept to me. I’ve always enjoyed my own company, so I didn’t get out much back then, either. I was an A student. I learned and understood everything they taught at school. The facts of reality, though, I learned on my own. At school, I taught myself to draw by practicing in the margins of my notebooks while my teachers went over the lessons again for the rest of the class. But I began to fear that I’d gotten the job only because I was seen as “black,” so I dedicated myself to developing my art to the point where it was so good that it wouldn’t matter what color I was.

Working mostly at DC Comics early on, you later moved to Marvel Comics for a short stint penciling Power Man & Iron Fist and a few assorted inventory stories, but then went back to DC for the majority of your franchise comics career. What was your experience at Marvel like and how did it differ from DC?

Both companies treated me like a “black” artist/person outside their main sphere of interest. I was a novelty to them — the black guy who could think (i.e. “like a white guy”). Anonymity and/or neglect never bothered me. It gives me more time to cultivate my own personal interests in privacy.

When I first went over to Marvel (on a whim), Al Milgrom took me over to [Jim] Shooter’s office. Shooter pulled out an old [Jack] Kirby/[Dick] Ayers Captain America comic and proceeded to tell me, panel by panel, what I should try to draw like. “Study this… and try to draw like this!” I love Jack Kirby! Best comic book artist ever! But I ain’t him. So I craned my neck backward and looked up at Shooter, right in his eyes (I’m 5’6 1/2", he’s what — 7 or 8 feet tall?) and said one word to him: “Why?” He stared down at me as if I had spoken in a foreign language and after a second of dead silence, turned to Al Milgrom and said (right in front of me) “Al, I’ll talk to you — you talk to him!” And that was the end of the meeting.

Sometime later, after he called me back into the office and fired me, I walked down the street into DC’s offices and picked up an assignment that same day. It never bothered me, to this day, that I’d gotten fired for drawing in my own style. It just bothers me, in hindsight, that I could have done a much better job than I did if only I had a little editorial support. But except for Jack C. Harris on Black Lighting in 1977 and Andy Helfer on Legends of the Dark Knight in 2002, no editor ever gave me feedback, ever.

The tenure you had over there sounds like a very short one. You never really worked for Marvel since the Shooter era, even after his departure from the company. Were Marvel’s doors not open to you or did the opportunity to retry your hand at the House of Ideas never present itself?

Working at Marvel never really interested me, either before or after my encounter with Shooter. As I've said, I'd originally gone over there merely as a whim. I've never actually given them a second thought, after that. This is somewhat peculiar, in light of the fact that most of the comics I'd read as a kid were Marvel comics. Jack Kirby, John Buscema, John Romita — these were my all-time favorite artists, ever. At DC, I loved Curt Swan's Superman, and Legion of Super-Heroes (inked by George Klein), and Joe Kubert's brilliant ink-brush drawings were a joy to behold. But all of my favorite comics in the early, long gone, and formative years of my youth and beyond were Marvel Comics.

John Romita's drawing style was one of the cleanest, sharpest, and most straightforwardly and dramatically effective that I've ever seen. His Spider-Man was the only Spider-Man for me (sorry, Ditko fans). That may not seem like much of a huge compliment, but it represents many, many years of loving enjoyment in the formative years of my life, to me. I can never forget the black-and-white story he illustrated in some Marvel magazine about the race of Amazon women, whose men were all slaves. I believe the queen was forced to kill the man she loved, at the end of that tale. I forget who wrote it, but the visuals of that story live on in my memory still [“The Fury of the Femizons” written by Stan Lee, Savage Tales #1, 1971].

John Buscema's incredible artwork (his romance stories were truly beautiful to behold) was quite simply beauty incarnate to me. The "Michelangelo of Comics?” Yeah, he fairly deserved that moniker. Don't think of that as a trivial compliment, either. Michelangelo is still my favorite visual artist, ever. He created visions of sublime and divine wonder in three dimensions (and in marble, no less) that I cannot even create in two, on a piece of paper. The restoration of the Sistine Chapel is an event that I consider to be the greatest boon ever bestowed upon the world of art in the 20th century. To have finally seen the actual beauty of Buonarroti's original vision and exquisite colors (and that superbly sensuous modeling) was the closest thing to Heaven I've ever experienced.

Marvel didn’t impress me. Still doesn’t. “The House of Ideas” died with Jack Kirby. Now there was a fountain of creativity. After waxing rhapsodic about the talent that was John Buscema, it may seem somewhat anti-climactic to mention the only artist at Marvel Comics even greater than he — Jack Kirby. About the King, I need say no more except that he was the King. Period. No greater creative force of pure and unparalleled imagination and energy has ever been unleashed upon the comics page. The man, the artist, was brilliant, profound, dynamic, philosophical, exciting, overwhelming, incomparably original, and above all — intensely and unforgettably human. We all know everything that there is to know about the King, we've all seen his work. Words of praise are unnecessary and superfluous. I remain proudly and steadfastly one of his faithful, loyal, and eternally grateful subjects. Stan Lee was a great dialogue writer; the great Marvel catchphrases are all his. He put words into the mouths of superheroes that delighted the young child in every fan, everywhere. But Jack Kirby created the ideas — the characters, the plots, the powers. To me, Will Eisner created the most literate comics. Kirby created a universe of fun, period! No other creator in American comicdom even compares to [his] individual thought… especially in the business of art, which is the business I’m in — and I take great pains to provide the best that I can offer. Artists can create worlds. Corporations can only sell ‘em. The Dream Maker and the Dream Factory are not one and the same. Only one can create original ideas.

By the time I'd grown up, though, and been allowed the privilege of becoming a comic-book artist myself, that sense of energy and excitement -- of true, original, unfettered creative expression -- had left the company that Marvel had become. Until Frank Miller came along and started to write a new chapter in their history. To the brilliance of his talent and efforts I would willingly contribute, but to Marvel itself — well, as I've said — The House of Ideas died with Jack Kirby, for me.

Your early style was fairly standard within the parameters of mainstream comic books of the late ’70s / early ’80s. Then with the Green Arrow miniseries, the Batman Annual #8 (both written by Mike W. Barr) and later on Thriller, you cultivated a unique style. What was that a result of? What were your influences, comics and non-comics, when you artistically came into your own?

The “style” I created was an individual approach to storytelling. The visual expression was tailored to each job’s specific requirements. My art is always an expression of my philosophy, and I’ve had one for as long as I can remember. My life is the training ground on which I develop and express the ideas that motivate me. My art in comics is one form of that self-expression.

When I discovered Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, it changed my life for the better — forever. This remarkable writer had managed to both answer many questions I’d had for years, as well as postulating new, original ideas and conclusions of her own. Her literary style was absolutely inspiring. She meshed fact, fiction, objectivity, and subjectivity into a powerful and educational work of Art. Her style was like a laser cutting through diamonds (or common sense cutting through bullshit)!

Alex Toth, whose work I discovered at Continuity, was my second influence. His work was abstract, graphic simplicity at its best. The exact opposite of Neal Adams’ “surgical knowledge,” Toth’s art was the important elements of any scene or situation, stripped to the bone, with absolute technical knowledge as its base. Neal piled layer upon layer of beautiful drawings into creations of technically perfect beauty, seemingly correct in every detail: it was pure thought made visible. Toth’s art, like Kirby’s, seemed to come straight from the artist’s subconscious: it was imagination made visible.

The other influence on me besides Rand and Toth was Bruce Lee. “Enter the Dragon” is my favorite movie ever, and I mean ever. Bruce Lee was more than just technically perfect, he had actual ideas that he was trying to communicate through the medium of film. The man was quite a prolific writer, an unusually profound philosopher, and an absolutely brilliant scholar on the martial arts. He transformed his skinny frame into a body of superhuman proportions, all through the force of his own will — in the service of expressing his own ideas. People forget that this human killing machine was a philosophy major in college — and a cha-cha dance champion in Hong Kong. Bruce made himself into a work of art. He was, in Ayn Rand's words, "the personification of strength made visible."

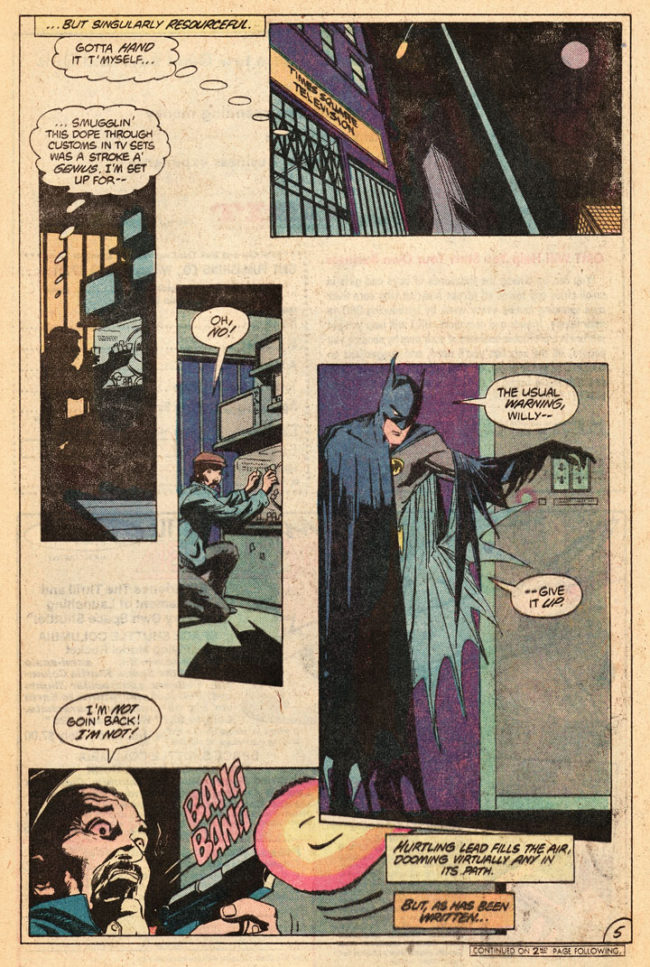

After many years, I created the Batman Annual #8 in 1982, which I’d managed to have colored by my girlfriend at the time, whom I’d met at Neal Adams’ Continuity Studios. It was her first job in comics. Her name’s Lynn Varley. She ended up doing pretty well in the biz. That was when this “dream job” became a happy reality to me! I still lived and worked in a racist society, but was never again in doubt as to my own self-worth. The Batman Annual was the culmination of many years of intense effort and serious dedication. Lynn and I finally consummated our relationship after I got this [Batman Annual] gig. I lost my virginity between pages 4 and 5. It was well worth the wait. Interesting where in the book it happened – before Batman’s first appearance!

One of my all-time favorite jobs, both art and script, was a [four] page story called "Second Chance," which appeared in Mystery in Space #114 in 1980. I still love that little gem. I had fun drawing those Green Arrow back-up stories in World’s Finest, mainly because he was such a difficult character to correctly draw. It was but one of many back-up stories in that book and it’s when I designed the villain, Count Vertigo (one of my personal favorites). I also liked the Green Arrow back-ups in Detective Comics # 521 and even more so, #522. It was during that time that I'd begun consciously creating a unique and individual style of visual storytelling, and page design, which reached its fruition in the Batman Annual #8. That book would not have turned out as well as it did, without Lynn’s presence in my life. For me, she was the one.

Who knows? Had I been allowed to continue drawing the adventures of Batman, after that annual, things might have turned out quite differently in my career. But then, I might not have ended up bumping into Bob Fleming in the hallways of DC Comics, and Thriller might never have been. Who knows? I tend not to speculate too much on the "what ifs" in life, though.

Did you have studio mates or any peers who influenced your work and your work ethic? How strong was the sense of camaraderie for you back in those days?

“Sense of camaraderie?” You mean “every man for himself?” That’s about it, as far as I could tell back then. Didn’t bother me; you don’t need a sense of “camaraderie” to become an artist but a co-dependent. You need a sense of self to be an artist. Meeting Neal Adams in ’78, and working for him doing advertising work while drawing Black Lightning, was the strongest and the most important influence on my work and my work ethic. As an artist and professional, Neal is impeccable. I learned just by being around him. It was all very Zen — he didn’t teach, I learned. Neal’s become somewhat infamous for his brutal honesty, in some circles. Those are the people I like to call “jealous assholes.” Beware of “jealous assholes” in every facet of your life and career. They exist simply to destroy what they cannot create. They lurk sometimes even in the hearts of those closest to you. They fade in the light of independence. My life is simple: I yearn to find the truth in any and every case. Those who consider “brutal honesty” to be a bad thing are people with whom I never choose to waste my time. I’m too damn busy finding out something important. That’s what life is for.

Here’s something that you might find surprising: Gary Groth’s review of the Marshall Rogers/Terry Austin “Joker Fish” series was so insightfully and intelligently written, that for the first and only time ever, I was inspired to create artwork worthy of that kind of review!* This is, and remains, the only time a critic’s work inspired me to better my own. I’d seriously like to reread that review, just to see if it was as good as I remember it to be. I’m sure it is, though.

I met Gary at a con a few years ago. He’d asked me to do a sketch for his nephew, I believe, and when he told me who he was, I insisted on doing it for free (conventions are a source of revenue for a starving artist). I always regretted not telling him that his [magazine's] review of Marshall’s work, back then, had helped me a great deal in creating my own. Oh, well.

*[The review of the “Joker Fish” era in Detective Comics, which was written by Steve Englehart and drawn by Marshall Rogers, was written by R.C. Harvey. Harvey’s article, "The Reticulated Rainbow," immediately followed the Marshall Rogers interview conducted by Gary Groth in The Comic Journal #54, 1980.]

Your versions of Batman and Green Arrow, being the characters that you mostly worked on and gained early notoriety for, are very much definitive: elegant, sharp, heroic. Did you have a fondness for the characters or did it just happen to be the assignments you were given?

I liked Green Arrow’s personality. I’m a sucker for independent-minded thinkers. The goatee was a bitch to draw, and it was quite a challenge to draw that Adams-designed costume. Much fun, ultimately, though. I loved Dick Giordano’s inks on my Green Arrow miniseries, by the way.

Batman is my all-time favorite superhero, ever. He’s “just a man” who raised himself to the level of commanding respect and admiration of super-powered beings — by his own efforts. And he keeps on going … and going. Batman is “man as superman,” by the power of his own will and desire. The best he can be and then some. Batman is a man worthy to walk among the gods. Man as scientist, creator, inventor, fighter, moralist. Man as a force for Good. Batman is also one of the richest men in the world! If I wrote Batman, I’d make use of this concept. Good use, that is. Batman is man at his best, period. My ideas for Batman are still far beyond the trite, generic creation he — or rather, his franchise — has become. But limited minds are always condemned to limited forms of expression. My Batman is not a scared, helpless, traumatized little boy at heart. He’s the Man who has overcome all that, including juvenile thoughts of revenge. My Batman would be really scary. He’d have no psychological scars to cripple him and make him more “identifiable.” My Batman would be an incredible engine of pure will power — a force capable of enormous destructive and constructive energy, held in absolute control, by a man you absolutely trust to be a force for good. Kinda like Bruce Lee in his movies — an absolutely lethal killer that you know you can trust implicitly but he still scares the shit out of you in real life. I guess now I know why I like Bruce Lee so much.

So, yeah, I like Batman.

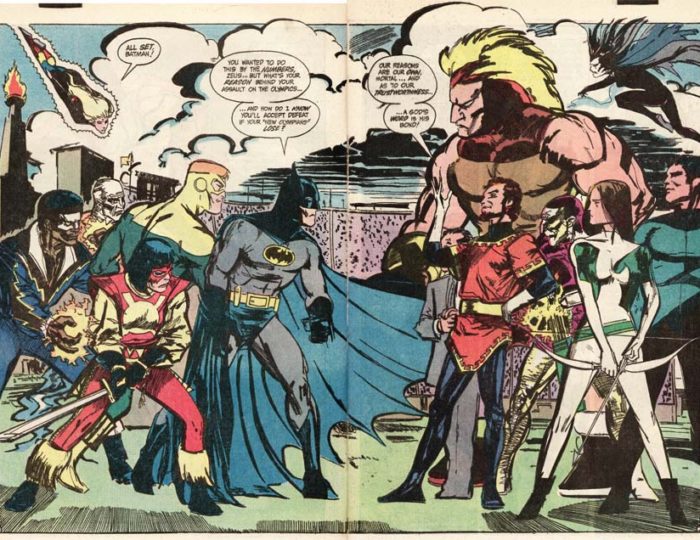

In 1984, you worked on the groundbreaking comic series Thriller with Robert Loren Fleming, who was a relative newcomer. How did that project come to fruition and how deeply involved were you in the creative process regarding story and art direction? Did you see Thriller as an opportunity to use the form as a vehicle for experimentation?

Thriller was an opportunity to use the form as a vehicle for original expression, never “experimentation.” I never “experiment” — I express what I know. The very term “experiment” seems incredibly arrogant, inconsiderate, and condescending to me. I can’t stress this enough. Whether or not it will sell — that, to a corporate mind which is usually full of clichés and stereotypes, is an “experiment.” I take great pains to both find out and express what I know. I intend to lead my life according to what I know and have discovered firsthand. I never believe what I’ve been told. I believe what I know. To a corporate mentality, it was an experiment on their part. Not mine.

Experimenting is not inherently wrong, though. I didn’t mean to imply your art was weird for weird's sake, but the concept of experimentation is the root of… well, everything. Accepting that premise, experimentation must be part of the equation in the creative process. I understand that you draw and work from what you know, yet I have to question if all of your work springs forth fully conceived without any experimentation whatsoever?

In my case, all the "experimentation" goes on inside my head. My visual art generally, almost always, comes from the desire to depict or illustrate a concept in my head. The concept's always in the form of a sentence or two. In my comics career, I'd have to "translate" my writer's ideas into concepts that inspired my art. The only "experimentation" I indulge in, is in creating the concept that I want to draw. As I'd said, I like to draw ideas. That's what comics are all about to me — telling stories. That being said, here’s the origin of Thriller:

Bob Fleming was working in the mailroom at DC when he bumped into me in the hallway. We went into an empty office and he told me his idea for the series. I was impressed and went to Dick Giordano with the idea — and Bob.

Thriller was not a mutual effort in script creation. Bob wrote all the scripts himself. He’d call me on occasion to run an idea by me for a reaction (they were all good) but I had no hand in the writing, whatsoever. I did design the characters from Bob’s descriptions, but I assumed that Dick, being an old hand in management, was helping Bob with the literary chores — development, creation, editorial suggestions, etc. I was strictly in charge of the art.

The first two issues of Thriller show my art at its supernatural best. My page/panel layout sense was designed to tell a unique concept in a unique way. The actual drawing – or finishing the image once I’d laid out the page and determined the storytelling – was an expression of the thrill I’d actually felt in bringing Bob’s ideas to life, and in working for one of the largest comic companies, let’s not forget. DC had treated me well after my “debut” on the Batman Annual a few years prior and the quality of my work was fueled by the fact that they’d let me alone and allowed me to do my work without interference. Money was never a factor. I was always told that my books did not sell, but that the editors gave me work because they liked my art. I was never aware that I had a fan following of any kind (one interview in Amazing Heroes and one convention appearance was the extent of promotion for the book). But as I said, anonymity never bothered me. I’m always busy working on something or the other in order to develop my art. Again, it’s worth every minute of every struggle I’ve had to undergo for its sake. Art is about self-discovery, and so is life – if you want to be happy in it.

Frankly, the only regret I have in my artistic life – my career as a comics artist – is the work I’d done on the later issues of Thriller.

To this day, Thriller stands as an underrated watermark in comics held in high regard by pros and fans alike. It’s safe to say that Thriller would not have been the same without your artistic input. Having said that, how do you feel about the notion that, as Thriller editor Alan Gold felt, “Fans believed they were in the presence of profundity because they didn’t know how to appreciate its elliptical narrative?” What was the overall reaction to such a project?

Fans were in the presence of profundity – with the first few issues of Thriller (especially the first two). It was the direct abuse and neglect of its editorial staff that murdered that book – very slowly. “Profundity” is not something “black” men were supposed to be associated with in American comics at the time. By this, I mean me, not fictional characters like Black Lightning, Luke Cage, or even the great African King, T’challa. Actually, when Jack Kirby created the Black Panther, fans were then in the presence of great profundity – a black man as king … gasp! But Kirby’s entire output was so profound, in and of itself, that the “blackness” of the character was never a factor. Kirby’s Panther was a king – period. But then again, so were all of Kirby’s heroes. Just like the man.

What Alan meant was that the editorial staff didn’t know how to appreciate (or understand) the book’s concept – much less its “elliptical narrative”— whatever the hell that means. The book was straightforward storytelling of an original concept. They just didn’t get it; others did.

The overall reaction from fans? I don’t know. The overall reaction from editors – they called me into the offices with “newbie” Alan Gold and tried to pull the “collapsing chair” stunt on me. If I’d not refused to sit in the only chair made available while my editor stood, my ass would’ve hit the ground, instead of Alan’s. After my third refusal to sit, he took the chair, to avoid a confrontation. He ended up with a pain in his ass. I ended up with a useful bit of information about the people I worked for.

Let me get this right: A prank that was supposed to be at your expense was intercepted by rookie editor Alan Gold. Why would this be done to you or anyone? Was it personal animosity, direct racism, commonplace in the office or just some sort of initiation? I've heard industry horror stories before, but I'm having trouble placing the motivation behind the "pranksters" and why such action was tolerated by anyone.

No, the chair incident was no prank. It was a corporate effort to embarrass me, and "bring me down to Earth," so to speak. Partly because I was an artist/employee on the rise, mostly because I was a "black" artist/man on the rise. No prank, but a power play, designed to humiliate. I wasn't humiliated – I was infuriated, and that was my mistake because in the end, it was my career that suffered, not DC Comics.

After Thriller #2, each job was done in successive stages of steadily mounting anger. This “chair” incident was never referred to again, nor was any attempt made to speak to me to at least find out what was behind the consistently deteriorating quality of my subsequent visuals. It took me a while to realize that editorial management at DC had no interest in my success as a legitimate artist in comics, whatsoever. If they’d wanted to help me make money or real fame in this industry, they’d have put me on Batman on a regular basis after the Batman Annual. Instead, they gave me assignments like the first part of a two-part story in World’s Finest #287 – but not the second – and the Green Arrow miniseries, because GA was one of their weaker selling characters who probably wouldn’t make me any money. Did the same thing with Black Canary later on – instead of putting me on the new Black Lightning series, which was also being published at the time, they put me on their weakest female character. Now, both GA and BL are appearing on Smallville on TV. Ironic, huh? Where’re my royalties?

The lesson I learned, in retrospect, is to never work in anger. That's my only regret regarding the Thriller years, and beyond. In that whole period (years), the joy of creation had left me--my work was full of anger and depression. Anger had replaced exaltation as my true motivation. And since my art always reflects my emotional state, it showed. But, I didn't care. Back then.

Hence my desire to apologize to the fans of the book – of whom I was always completely unaware, due to what I'd been told.

Robert Loren Fleming left the book after writing seven issues and you left after the eighth. A book that was a product of your combined visions with Fleming ended with a different creative team. What is the story behind the demise of Thriller?

First of all, the little bit of my soul that got squashed beneath that chair Alan sat in, grew bigger and bigger every day, since then.

Specifically, here’s how it went down in chronological order:

Thriller #1 and 2 – I’m literally thrilled to be able to do my best on this new series.

Thriller #3 and 4 – New and inexperienced editor on board (“Hey, let’s make it as hard as possible for Trevor to succeed in the industry, why don’t we?”) Then the chair incident. The beginning of the end.

Thriller #5 – Elvis appears. I don’t know why. I’m a huge fan of early Elvis, but it seems like a gimmick to me, for a book this original. Still, I like Elvis, so what the hell, I ain’t happy, anyway. Dick Giordano calls me in and asks to ink the book. He never once asks me “What’s wrong?” or even “Your inking’s been slipping – any reason why?”) No, he asks me if he can ink the book, that’s all. I say “sure” – if Lynn Varley can color it. This is the only other issue besides the first two that I still like. Especially the cover.

Thriller #6-8 – Lynn had colored (or was about to) a Daredevil book for Frank Miller, whom she’d met at Upstarts, along with Walt Simonson and Howard Chaykin. I suspected her of seeing Frank behind my back and confronted her about it. She admitted that it was so – “she loved him but didn’t know if she was in love with him … ” Oy! As soon as I heard this, I left. I’m not stupid … and I had a lot of other things on my mind.

After Thriller #6, which was drawn in the most depressed period of my entire life – betrayed by my co-workers, betrayed by my girlfriend, I was as blue as I could possibly be – DC literally begged me to do issues #7 and #8. I believe Fleming had already left. I was completely disgusted with everything at this point, but what really hurt was that it showed in my work… and nobody cared! It was like they were happy to see me fail. I couldn’t understand this at the time. Now that I work with the fans in mind and not the editors, I understand it perfectly. My fault.

Then I got a call from Lynn. She and Frank had rented a house in Montauk, and she wanted me to come by and meet him. What you have to understand is that before I’d met her, Lynn had been victimized in a number of relationships that had almost destroyed her self-esteem as an artist and as a person. I spent three years with her; I loved her more than I’d lusted after her, and it meant a lot to me that she was aware of her own worth. When she “relieved” me of my virginity, as I’d mentioned, it was after I’d told her that she was going to succeed with or without me, and I meant it. So, when she started seeing Frank, I was afraid that she was regressing back to that previous state of mind (my depression at the time sure didn’t help, either) and I was more upset about that than that she was seeing another man. Happily, I saw that Frank really loved her. She was speaking to me once and I happened to glance over at Frank – and I saw such a look of joy, wonderment and pure love on his face as he looked at her that I remember it to this day. I almost got jealous.

So I gave ‘em my blessing and went back to my own problems, my heart much lighter than it’d been before. Things worked out well for all three of us, as far as I’m concerned. Lynn’s happiness is my own.

Do you guys still keep in touch?

I was invited to the Sin City premiere (Lynn’s idea, I later found out) a few years ago. When the movie ended, the audience was dead silent, as the credits rolled – you couldn't tell if they loved it or hated it. I got up to run down to where Frank was sitting. I was in the middle of the back row, and the people got up to let me out – then promptly sat down again, to stare silently at the credits. I swear, it was like a scene from The Twilight Zone. I found Frank, staring at the screen with the famous Frank Miller frown on his face, touched his arm -- and could only mouth the word "Wow!" when he looked at me. His face broke into a big smile – and at that very moment, the lights went up, and the audience erupted into applause. It was also at that moment that I noticed Lynn at his side, and blew her a kiss and a smile. She leaned over as I started to leave, and asked: "Are you coming to the movie afterparty?" I hadn't planned to – until that moment. She looked the same as when I'd last seen her – 20 years ago. We spoke briefly, I gave her a real big hug -- oh yes, I'm only human – and told her how I happy I was for her. She seemed sad about something to me, but it sure wasn't because of seeing me again. That hug was way too warm for that. But unfortunately, it turned out that her father had just died, shortly before the screening. I found that out later, when she called me, about two months after the event.

It was in the middle of the night, about 2 a.m. She asked if I could meet her in the city, later on, that day. I said "Sure" and hung up the phone, slightly numb from my toes up.

We spent one entire afternoon together – walked through Central Park together for a while, spent a couple of hours at the Met Museum (which was much fun), the lakeside boathouse, and then back through the Park again.

She had a lot on her mind to tell me. She talked more in those few hours than she did in the entire three years that we were together. She wanted me to know that she had left Frank, and was moving into a place of her own in the city (nice neighborhood, near Central Park) – apparently he'd been neglecting her as a consequence of his runaway success with the Sin City movie, and in her own words, she "wanted to be with somebody who loved her although was not necessarily in love with her." She was always very big on the difference between those two states of mind. Well, my essential dilemma has always been that I do love the woman – so I told her, in no uncertain terms, that she knows that she was the muse, the inspiration, behind my success – that she was obviously the same for Frank and that, most importantly, it was now time for her to be a source of inspiration unto herself – to see in herself what is/was so obviously there, to Frank and I.

Don't get me wrong, the temptation was sometimes overwhelming, to take advantage of her and all she that now had to offer, especially in this vulnerable state, but I like being able to sleep at night with a clear conscience. So I gave her the kick in the pants she needed to keep on going and I let her go. The very last thing I said to her over the phone was "Lynn, you'll never get anywhere by being a coward!"And then after a short pause, she hung up on me. I never heard from her again.

Two months later, on my birthday, I found out that I'd finally be getting my chance to write and draw The Original Johnson, a book that no gigolo could have ever written by the way, lemme tellya! And, oh yes, I'm no fool, I had managed to give Lynn a copy of the first nine pages of TOJ, in written and penciled form, when we met. I'd told her that this was the book that I planned to write – long before the project had been sold. She later read the intro but never got around to telling me what she thought of it. I was too busy telling her the things that I thought she should know – along with all the things that I wanted her to know since I knew I'd probably never be seeing her again after I did. I'm very glad about that. I later learned that she did divorce Frank, to live on her own.

Wherever she is, I hope she remembers my advice – and I hope that she likes my book. All I ever really wanted from Lynn is all I've ever really wanted for Lynn – I want her to be happy. That's all. I hope that she is.

Your comic art remained unique and innovative after Thriller, though it wasn’t long before there was a notable turn in your style. Having other inkers work over your pencil art may or may not have affected your artistic foundation, but it comes to mind as a prime indicator of that shift. You actually never inked yourself again, which was part and parcel of your art. Also, the more design-heavy experimentation of page layout and pacing was replaced by a more traditional approach. Were all these changes in style a natural and personal progression or was it more in tune with editorial demands?

I did ink myself again after Thriller, but very badly. At this point in my career (circa ’85 – late ’90s), all the joy had gone out of my work. I still loved my job – drawing comics – but comics are about storytelling. The incredible mediocrity of the scripts I’d been given after Thriller inspired nothing but ennui. I certainly wasn’t about to do my best work for those scripts. I did a lot of advertising work to pay the bills, but I couldn’t give up comics. I just loved the creative freedom and untapped possibilities that the medium held. There was no joy in creation where mediocrity was concerned, but life was and still is a learning experience for me.

One can learn a lot by observing oneself under the worst circumstances. An open, alert, and honest mind saves one from repetition of many mistakes in life. My mistake was allowing the seeds of my creative expression to lie in hands other than my own. But that, too, is part of experience. It’s all a process of learning. My work in this “black period” of my career was a result of personal depression (anger turned inward, 'tis true) and editorial neglect. I later realized that this “hands-off” policy, in regard to me, was neither flattery nor a show of confidence – it was racism, pure and simple.

At this time, around 1996, I began to write my Jack Johnson book. I’d always recognized a kindred spirit in Jack, but it wasn’t until I read his views on racism – he allowed it no place in his consciousness – and read the last sentence in his autobiography, that I knew I had to tell his story, from a “black” man’s point of view for a change: “As I look back on my life and compare it to the lives of my contemporaries, I consider mine to have been a full life, and above all – a human life.” The last three words are what got to me. Y’see, my idol, Bruce Lee, had always said that he wanted to be remembered not as a “superstar” but as a human being. That’s what Bruce was all about. Thing is, Bruce idolized Muhammad Ali – and Ali’s idol was, of course, Jack Johnson. Three nonwhite human beings that changed the world – simply by being human in an inhuman society.

I wouldn’t say that your work was inked badly at all; it was energetic and instantly stood out. Although you say that you were depressed and aggravated with comics, the art on some of that post-Thriller work seems highly inspired. It’s as if your frustrated state of being inadvertently led you to get looser and bolder while retaining structural control. Your last two World’s Finest issues and a few Outsiders stories immediately come to mind. Clearly, you were still responding to something beyond your professional task or personal woes.

All of my art is an honest and direct expression of my state of mind, at the very moment of creation. To me, that's mandatory, in being an artist. But the "looser" aspect of my line work is actually what displeased me upon later viewing of the work. My pages are always laid out first in light pencil, at which stage I concern myself solely with panel-to-panel-to-page design, and the relationship of the elements within each panel to each other. All this is in service of the most dramatically effective and aesthetically pleasing way of telling the story. Once a page has been drawn in light pencil, I then finish the images with a darker, #2 pencil. After that, I ink it. The "looser" quality of the inked line work that you found so bold and expressive, would have been more pleasing to me had I taken the time – or felt the desire – to refine it further. It's much like writing feverishly in the grip of a flood of emotion when your pen seems almost incapable of putting down your thoughts with the rapidity with which they occur, the quality of your handwriting (its legibility) suffers, despite the content and meaning of the words written. The same writings, words neatly printed or typewritten, are much more effective in this more legible form. The ideas expressed are more easily communicated to the reader, without the unnecessary distraction of having to interpret and/or decipher words written in a fevered rush.

Fellow artists might find this interesting, being able to understand and relate to the creative force behind such "bold and loose" scribbling – much as a pharmacist is able to decipher a physician's seemingly incomprehensible hieroglyphics on a prescription – but to the layman, or average reader, this is an unnecessarily distracting chore. I pride myself in my best work, on refining my line-work to the point at which it clearly expresses my intentions without the loss of any dramatic effect or power. Much of my post-Thriller inks, fueled by prolonged bouts of profound depression, lack this necessary refinement, or "professional polish," from my point of view.

It's like seeing the raw, rough, first draft of a script that someone has written, replete with mistakes, redundancies, and rough passages – expressively revelatory to a fellow writer – as opposed to the final draft of the same material, refined, edited, and made ready for public consumption. The same work, just in a more easily accessible form to the reader. My general state of mind at that time, combined with a pronounced lack of interest in the mediocre scripts I'd been given to illustrate, precluded this final "polishing" of my inks during this long and dark period of my life. Instead of letting pages sit for a while, and coming back to them later, in a clearer state of mind (quality checking) as is my usual method, I'd literally finish 'em – then get rid of 'em by handing them in as soon as I was done. The joy of creation, in my finished inked drawings but not in my page design or storytelling (which remained consistent – the "structural control" you'd mentioned), was noticeably absent from my mind in this period. It's that very joy in creating and expressing a part of one's own soul in the elements of one's art that propels an artist to polish, burnish, refine, and just plain caress his creation, to its absolute peak of expressive perfection before final presentation. Just look at Michelangelo's sculpture and then remember how they'd all started out as crude, ragged, and unrefined blocks of rough-hewn marble stone.

To me, this is what being a "professional artist" is all about. Not just expressing your soul honestly, but also expressing it to an audience – keeping their wants and needs in mind as well. But please don't forget – in my mind, my audience at that time were not the fans, but rather the editors for whom I'd worked – and frankly, Michel, I didn't give a damn about them under the circumstances in which I'd found myself.

All that said and done. I am happy to hear that some kind of positive energy did manage to rise up out of the murk and impress itself, in some form, on the sensibilities of some of the comics-reading public, despite my depressed and angry state of mind. I don't share that view, of course. I wish, in hindsight, that I had taken the time to execute my visuals with more dispassionate deliberation and less passionate emotion, but in my troubled state of mind back then, that was just simply not possible. My art, specifically the quality of my inked line work at the time, was cathartic rather than communicative, in both its nature and intent. Frankly, that's what I really regret. A professional should always put the needs of his clients (in my field, the readers) first. To this day, that's what I truly regret not having done, during those dark and depressing days of my early career.

Cont.