"I'm trying to draw as well as I can."

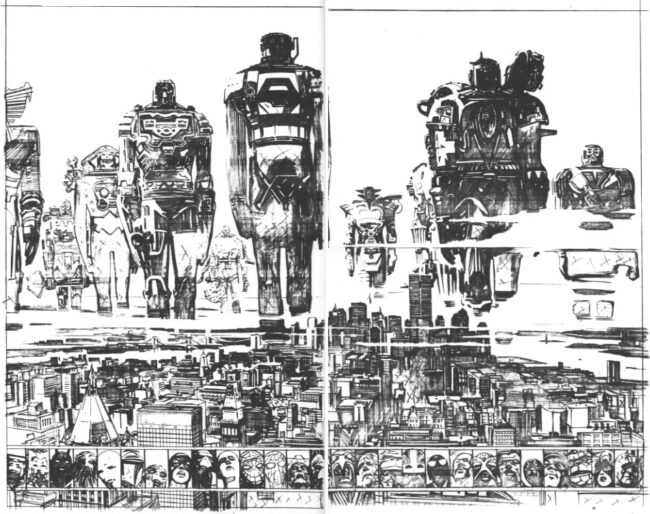

When John Paul Leon was on David Harper's Off Panel podcast, he was asked about the gravity he brought to something like Earth X, a Marvel expansion of a fun thought experiment envisioning its characters in a dystopian future, initially made for a Wizard magazine article. He was asked if he knew that his style would bring an uncommon believability to a scenario like this, and at first he didn't know how to answer; the quote above was his response. Listening to him struggle to address the idea of "consciously choosing an approach to a project" is something I can relate to. As an admirer of Leon's work, and as a cartoonist myself, I recognize how bewildering the question is. It's one that I might have wanted to ask him too, but I have enough drawing experience to know that it comes from a place of the after-the-fact observer. When drawing, you're just consumed with finding a delicate line where efficacy and excitement benefit each other, where what-the-brain-wants-to-see and what-the-hands-want-to-make find common ground. Or, as Leon puts it to Harper, he keeps working things out until he gets to a point where he "believes what he's drawing", no matter how absurd.

John Paul Leon passed away on May 2nd, at the age of 49, after a third battle with cancer. He grew up in Miami, to where he would eventually return, but he broke into comics while still attending the School of Visual Arts in New York City. He was well into drawing the launch of Milestone Comics' most famous title, Static -- written by co-creator Dwayne McDuffie and Robert L. Washington III -- before he graduated. He leaves behind him a gargantuan legacy in the comics industry, frequently pegged as one of those "artist's artists", mostly for two reasons: his work and name are held in reverence by a vast number of mainstream western cartoonists; and, by and large, his work has gone either uncollected in the trade market, or suffered from low print runs and high markups in book form. Even now, collected editions of his seminal series The Winter Men, with writer Brett Lewis, sell for $150 online on a good day.

Leon's approach to comics was story-driven before all else. The Alex Toth influence is clear: his thick blocky contour lines; his method of shorthand; and high-contrast backgrounds. Also apparent in his style is Toth disciple David Mazzucchelli - his early Milestone work feels very reminiscent of Born Again-era Mazz. Almost from the very beginning, with Static #1, Leon's layouts and attention to subtle framing choices felt astronomically more considerate than the average barely-even-20yrs-old cartoonist. Later on, in Earth X , and his landmark, The Winter Men, I see a reserved drama in his layouts combined with a photorealist approach to faces that also remind me of greats like Arthur Ranson. His tendency to create shadowy depths in his backgrounds and mechanical designs have an angular brush marker geometry to them that even recalls Yōji Shinkawa's concept work for video game designer Hideo Kojima. Leon's work is stark, to say the least, but without the frozen-in-time feeling that a style like that can often bring.

Leon's career spanned nearly 30 years, starting with the Robocop: Prime Suspect miniseries for Dark Horse in 1992. He soon moved on to becoming one of the initial artists for Milestone, where he stayed for a while, developing the look of the line through interiors and covers. After penciling the first 9 issues of Static (1993-94), he drew fill-in issues across the Milestone catalog, eventually penciling 16 issues of Shadow Cabinet (1994-95) - maybe his least talked-about work, but it's the longest run on a series he ever had, and a really wonderful growth period for him. Throughout the '90s he remained a penciler, working with a long list of inkers. He moved on to Marvel, penciling The Further Adventures of Cyclops and Phoenix (1996), notably inked by Klaus Janson, then returned to DC for a Challengers of the Unknown series (1997-98), and capped the decade off with the previously mentioned Earth X (1999-2000), which seemed to bring him a new mainstream notoriety. Through all this, and until the end of his life, Leon filled his breaks from interior work with a substantial amount of covers, and became a fan-favorite for them - notably the majority of Vertigo's DMZ and The Sheriff of Babylon.

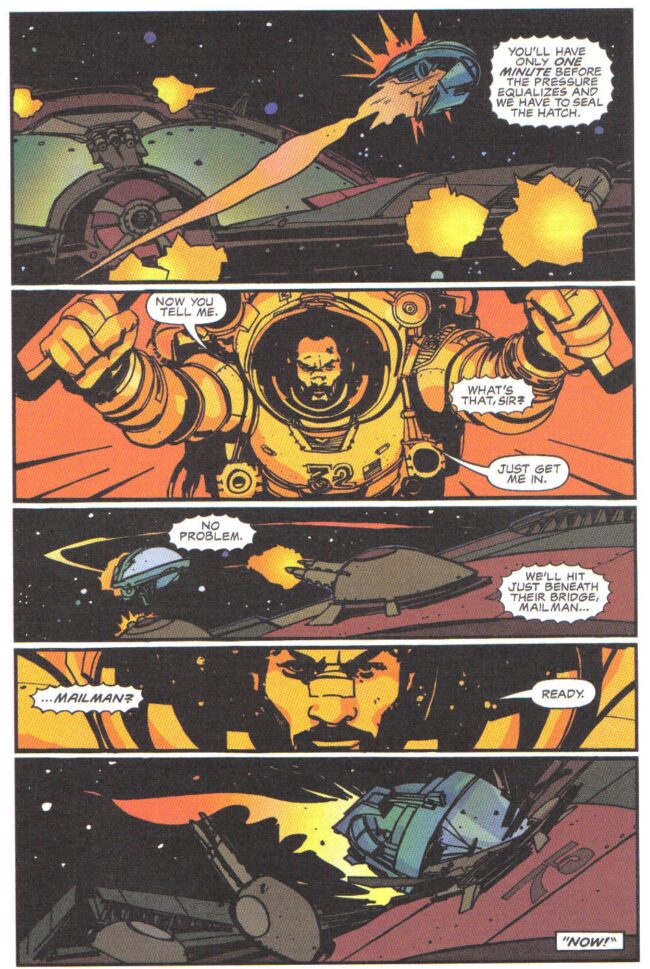

The 21st century saw him developing The Winter Men (2005-09) with longtime friend and SVA classmate Brett Lewis. They'd previously collaborated on an odd licensed adventure comic about Utah Jazz basketball player Karl "The Mailman" Malone (it's surprisingly great - "Best selling comic in the history of Utah," per Lewis). Here is where he began inking the majority of his work, shown off keenly in The Winter Men. He seemed to fall in love with inking his own pages, and here I see a greater dimension to his work, a new chapter starting. Leon's career goes a little all over the place from The Winter Men, drawing single issues or segments of issues for everything from Captain America to Gen 13 to The Spirit, while also taking jobs in Hollywood making style guides for DC movie properties like Superman Returns and Batman Begins.

He eventually returned to a committed series all his own, a Batman passion project with Kurt Busiek titled Batman: Creature of the Night (2018-20). The project was plagued with delays, as both creators struggled with worsening health issues, but it marked a new phase for Leon, as he got to pencil, ink, and color it all himself. The fourth and final issue came out last year. It's beautiful.

Listening to Leon speak, he has an affable everyman personality, unassuming and grateful. You can hear his love for the history of comics and commercial illustration in his voice, but at a remove from the fan culture surrounding his job. He seemed to love approaching comics as nonstop puzzle-solving; the fact that he drew fantastic scenarios of people with ridiculous powers was just a fun perk for him.

Filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni once said something to the effect of 'there are two types of film: one where the camera follows the actors, and one where the actors follow the camera'. I often think about how this applies to comics. One easy, broad way of thinking about that difference could be: "Are you sacrificing a powerful composition of a scenario as a whole for the sake of a character's powerful emotional presence, or vice versa?" In Leon's pages, I see a constant vast scope to the worlds he's drawing, gazing upon figures from a distance in cluttered, lived-in backgrounds. But always, I see an intimacy of mannerisms - an interiority-from-a-distance, that makes me, the reader (the camera), want to 'follow the actor'. This is especially effective in The Winter Men, a story about cold, inscrutable men, where showing intimacy and interiority any other way might feel forced and unearned. I can feel the protagonist Kalenov's thoughts and feelings being withheld from me, as they would if he were there in front of me, even when there's ample narration from him. But through Leon's careful, slow-burn examination of Kalenov's motions, he makes me want to be let in. I feel rewarded for every small glimpse into his reactions, his posture - and a window into his soul slowly builds, as I begin to know him more than he would ever want me to.

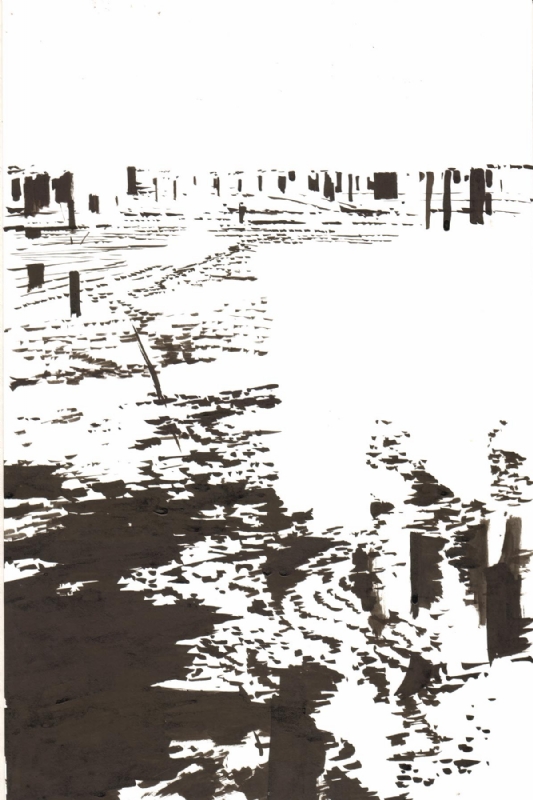

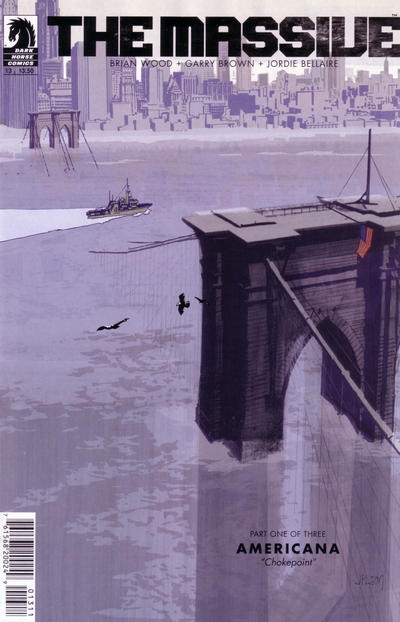

Years ago, I found images of a cover Leon drew for Dark Horse's The Massive, issue #13. He drew it in layers on three separate pages, blending sharp line art, brush work, and wash textures together for the dramatic effect he was looking for: a scene of New York City flooded from rising ocean levels, to the point that a fishing boat is sailing over the Brooklyn Bridge. Finding this, I felt a more personal connection to Leon's work than I ever had before, because this is something I do frequently: foregoing digital methods for an archaic-but-more-graspable-to-me physical way of controlling the elements of an image by drawing multiple pages of layers for an effect. I never had the chance to meet John Paul Leon, but looking at that cover specifically makes me feel close to him and his work. The legacy of his creative comics output is profound, and the outpouring of testimony from friends and colleagues show a man of great warmth and kindness, a combination that seems much too rare.

John Paul Leon is survived by his wife, daughter, and older brother. A memorial fund has been set up by his friend and fellow cartoonist Tommy Lee Edwards, to help his family. If you can spare it, please donate here.