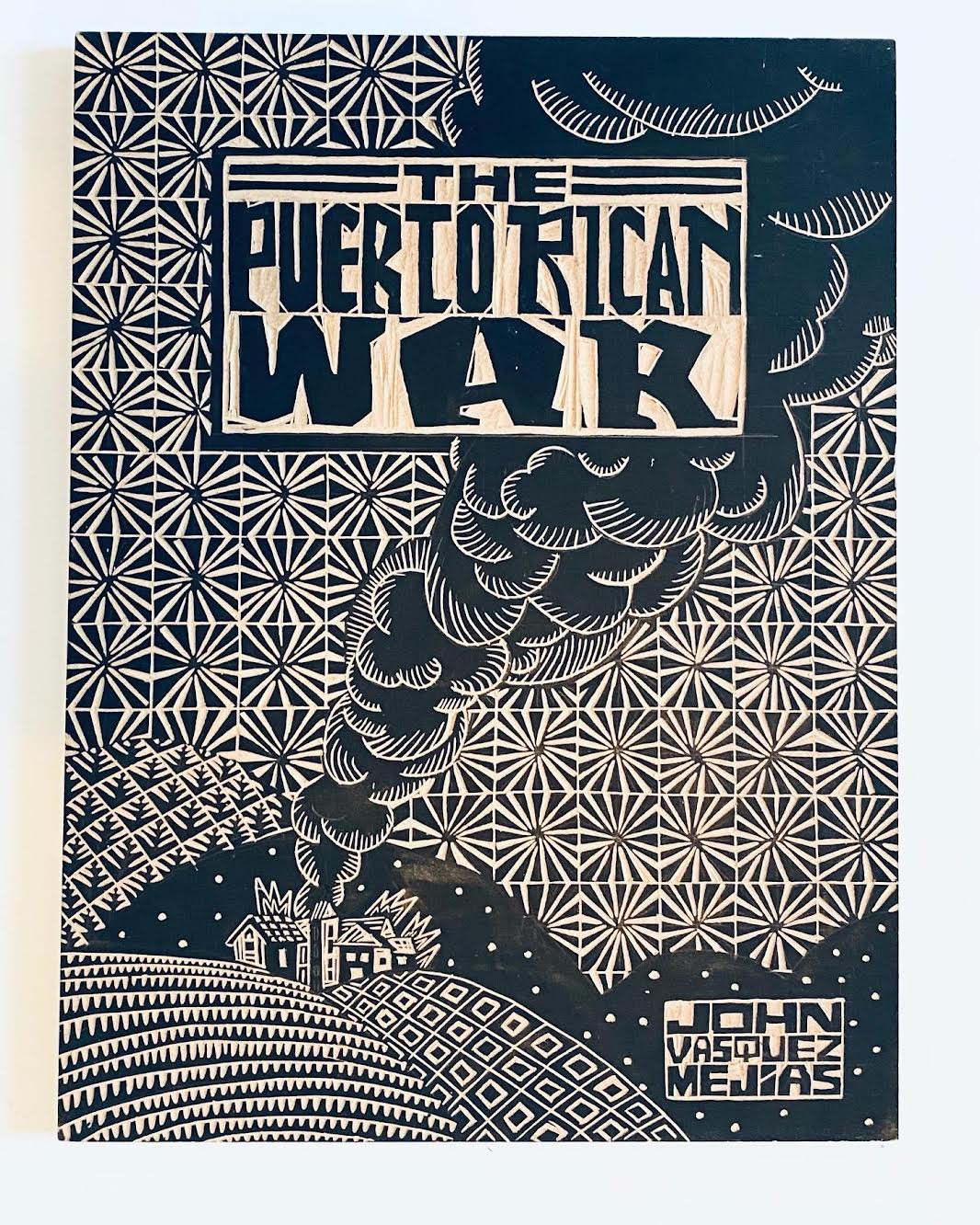

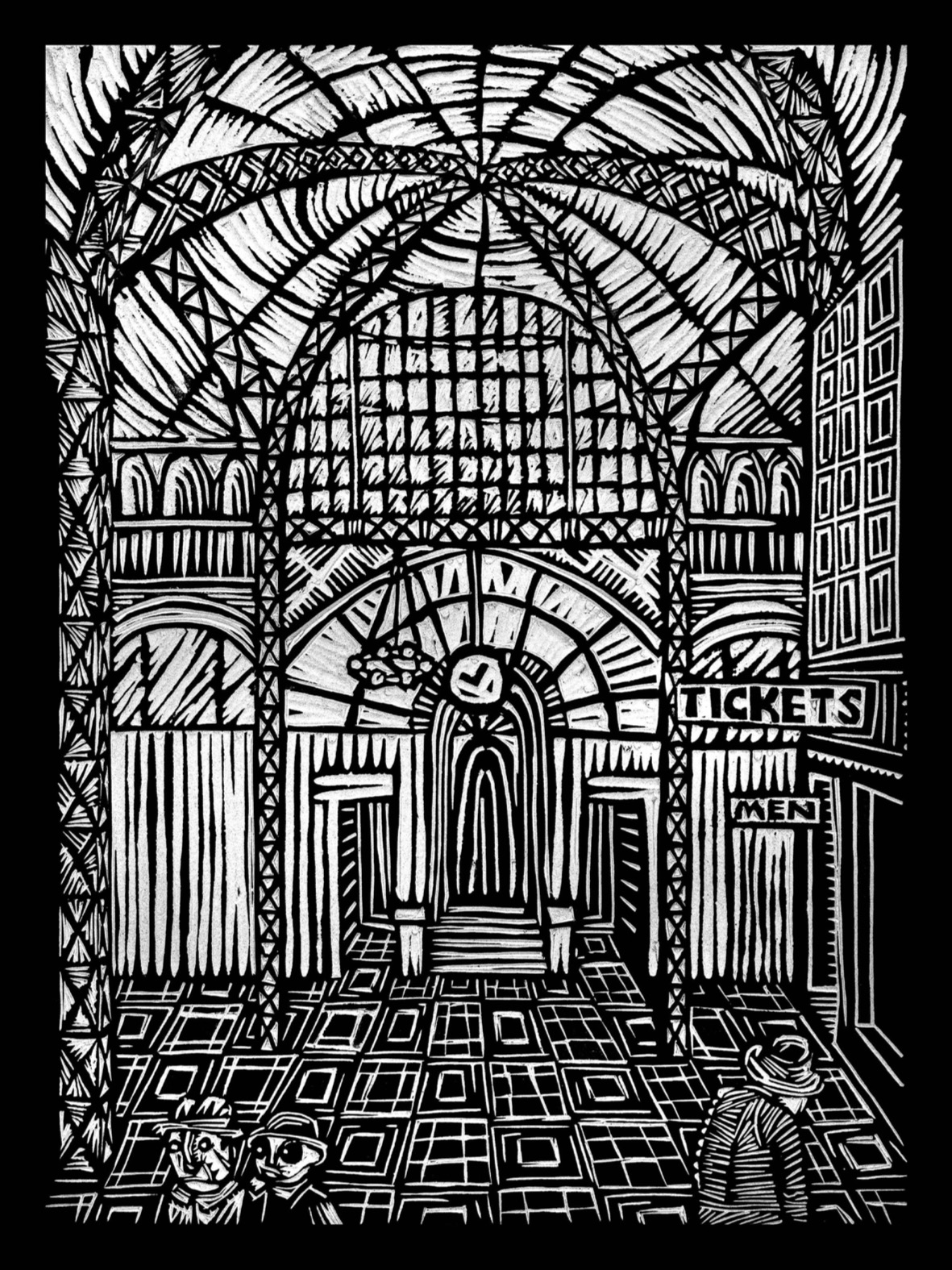

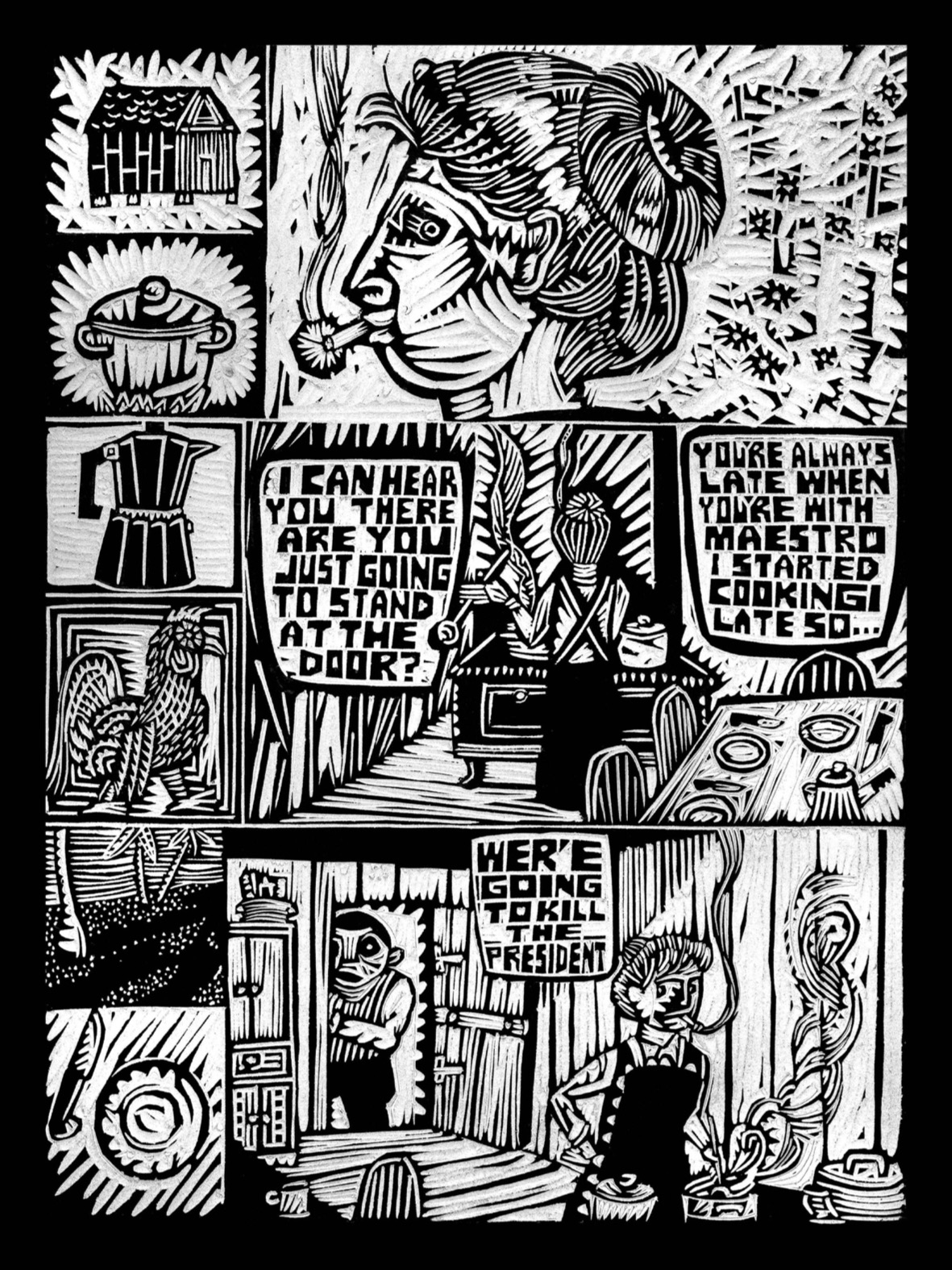

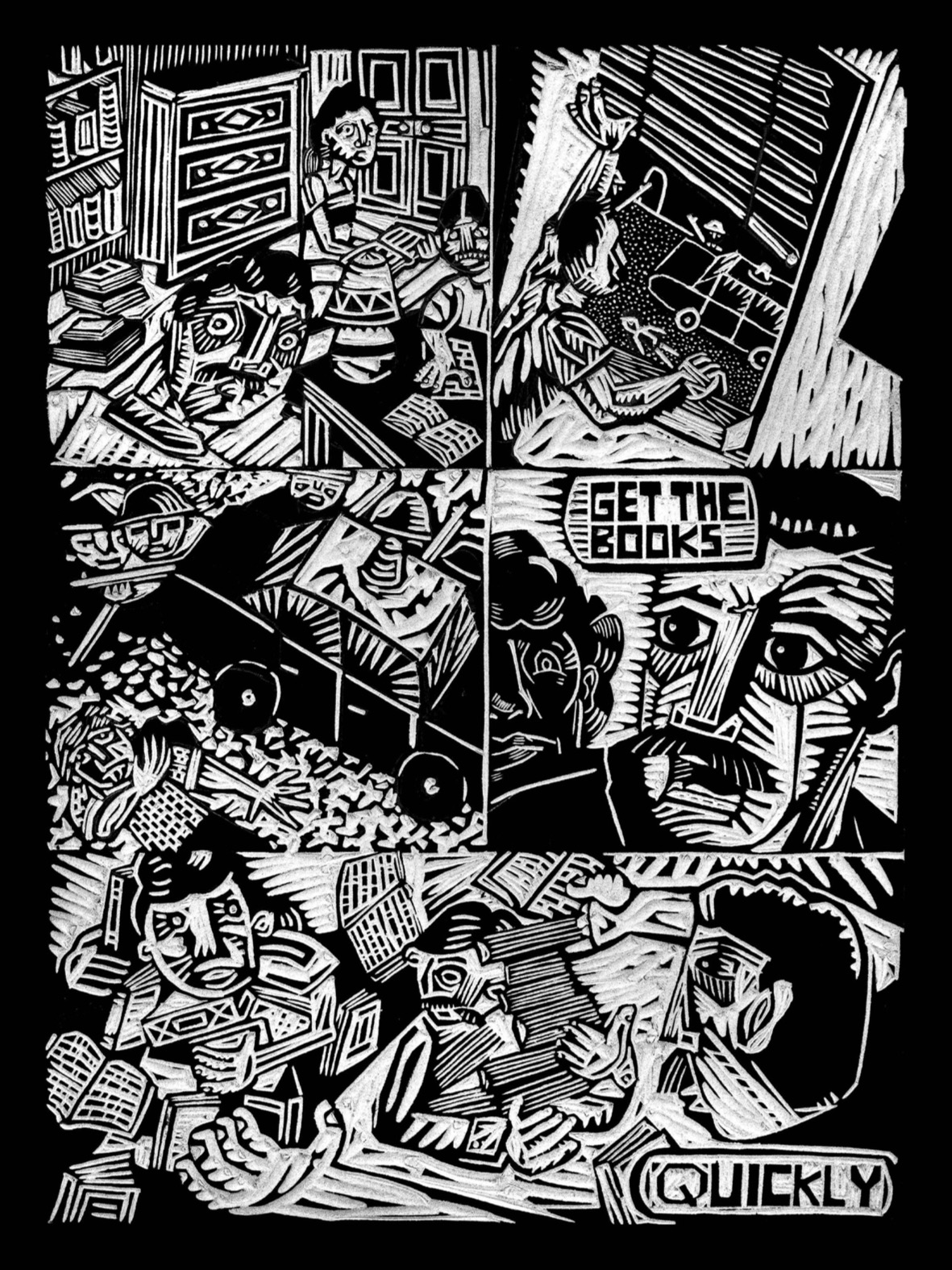

John Vasquez Mejias is a writer and artist, printmaker and puppeteer, storyteller and art teacher, best known for his self-published book The Puerto Rican War. Detailing a little-known group of Puerto Rican revolutionaries in 1950, the woodcut novelette manages to be a deeply impactful accounting of history as well as a striking work of art. Mejias had been working on the book for many years, but he’s been making woodcut prints since he was in college, in addition to a number of short comics which he will collect in an upcoming book. Mejias admits to being amazed at the reach that The Puerto Rican War has had, which has led to invitations to contribute to MoMA’s Magazine, where he carved a comic about his response to the exhibition Frédéric Bruly Bouabré: World Unbound, as well as his participation in Past/Present/Future, an exhibition at the Thomas J. Watson Library/Metropolitan Museum of Art. Currently working on a book about the Puerto Rican revolutionary, Lolita Lebrón, Mejias was kind enough to talk with me about the comics he drew in elementary school, making murals, and why he built puppets to avoid giving book talks.

-Alex Dueben

* * *

ALEX DUEBEN: Now I didn’t know your work until The Puerto Rican War, so I have to ask, what’s your background?

JOHN VASQUEZ MEJIAS: Long ago my parents came from Puerto Rico to Spanish Harlem. I always tell people it was like West Side Story but they didn’t intermingle or sing or dance. Then they achieved the dream of dreams of every Puerto Rican, which was to get a house on Long Island. They had me and my sister. They had a front yard and a backyard. They were like kings. [Laughs] Me and my sister were treated quite nicely and we were in the suburbs of Long Island and then when we went to college my parents said, we hate Long Island, we’re moving back to the city. And they did. My parents were real New Yorkers. Although now that they’re older, like every Puerto Rican, they have a place in Florida. So the typical road.

In terms of comic books, I always loved drawing. I think every artist was a kindergartener drawing in the corner. That was the same for me, too. At all the newspaper places near me, there was a spinner rack. I come from the spinner rack days where just with some change, I could buy this issue of Daredevil and I have no idea what’s happening so I have to keep buying it so I can understand the story. I just kept doing that. It was easy to get into because it was 75 cents. I had my own superhero, Mooseman. He had the power of a moose. I kept a deadline and put it out myself and would give it to my friends. He was basically Batman, but he had the powers of a moose. [Laughs] He had antlers on his helmet.

How old were you when you were making this comic?

Grade school. Probably like fifth grade. I was very serious about it.

If you were giving yourself a deadline and printing copies, that’s serious discipline, especially at that age.

I had other heroes. I had the Harpoonist, who was basically Hawkeye, but he had a harpoon gun instead of a bow and arrow. [Laughs]

That feels very Long Island.

Exactly! He went out to the Sound and fought crime. [Laughs] His motorcycle was called the Blaze X68, but I have no idea why. And I played Dungeons & Dragons. I liked metal and punk. As a teenager I would go to the city any time I could. I could not wait to be in the city and have that city artist life - which I did when I graduated college. But you asked about printmaking. I was always drawing thick and chunky and angular. I had seen some German Expressionism that I did not know were woodcuts. I thought they were drawing or painting that way. Then I took a printmaking class at SUNY Purchase and did some woodcuts and I thought, this really fits into how I draw. Everything is thick and chunky and angular. Then I realized that all that German Expressionism work I liked were woodcuts. I always tell everybody that I woodcut better than I draw. I draw okay. I’m not terrible. But when I’m woodcutting, the tools make their own marks and you’re subtracting. There’s already a lot of black in the area that you’re taking away from. It’s its own thing. It can’t really be copied. I’ve tried it on the iPad, but they do not copy well. [Laughs]

So you’d been drawing with thick lines because you were just drawn to it?

That’s just how I dance. That’s how it would come out. Instead of a ballpoint pen, I would always grab a big thick sharpie, so when I started woodcutting, it was like, okay, this is what you do. Although it was a very long time before I started making woodcut comics because it was so slow. I’m talking in the 1990s when I started making woodcut comics. I would write in the text by hand because I thought I could never carve all the text. Although I do now. A thing that took four panels would take me a week. After all this time, I’m faster and have more confidence. People tell me, "oh you carve so fast." Yeah, it took me a few decades to be able to carve this fast! [Laughs]

So when did you start combining woodcut prints with comics?

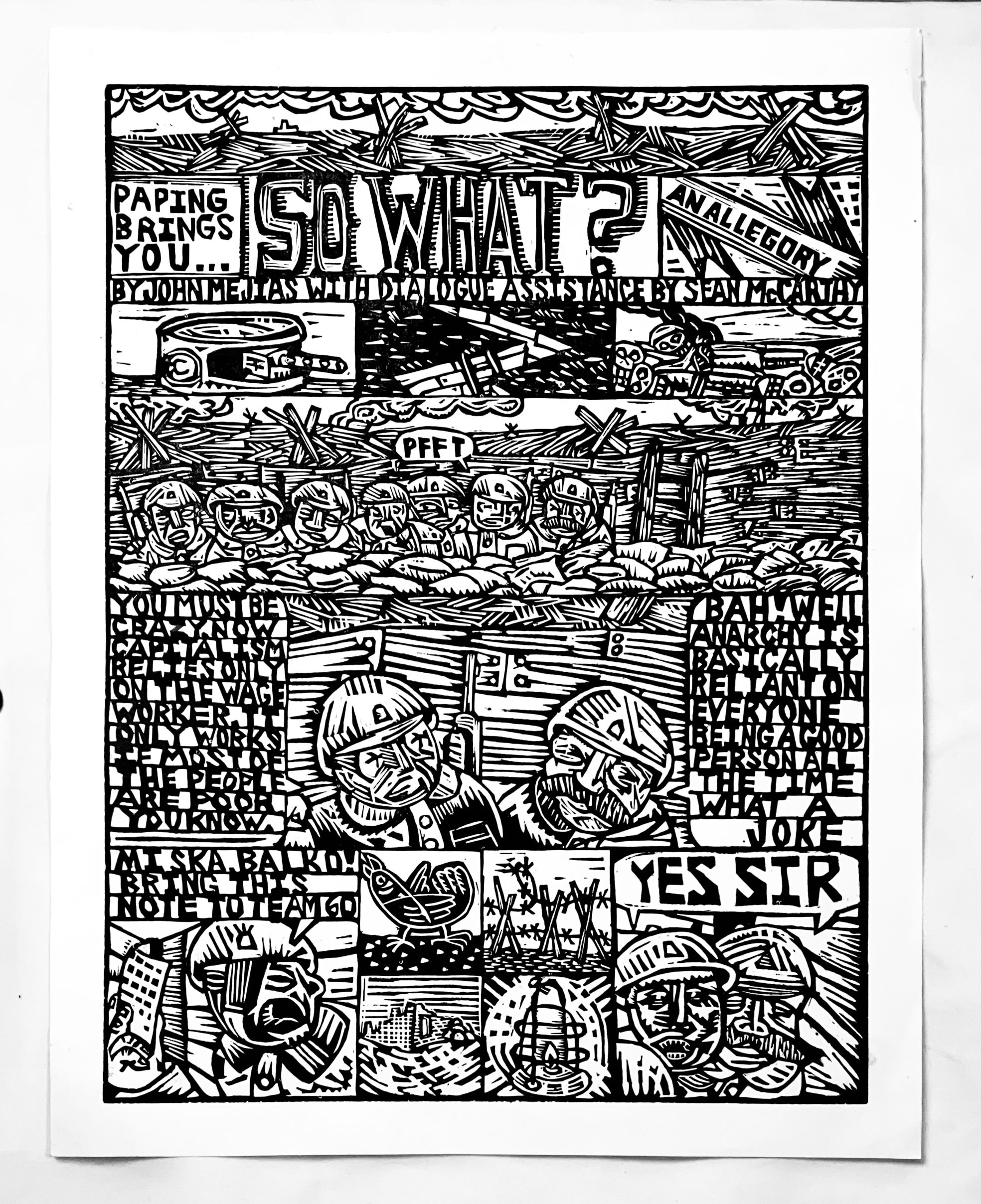

I had a zine called Paping when I was an undergrad. I was making my serious art and making my zine on the side. One day I did a very short story about my dad selling flowers on Mother's Day. He had to sell every single flower to make a profit. It was four pages and it was wordless and it was all woodcut. It took me forever but when I stepped away from it, I saw: this is something. This is next level. I felt good about it. I loved the way it came out. All my friends were like, "this is really something." Then I did it again but I made a story that had words. It was this autobiographical story about going to the city. Then when I graduated and became a school teacher, I was teaching art in the Bronx and keeping a diary of what it’s like to teach. I was like, I cannot woodcut this whole thing. I would make eraser stamps and I would draw with eraser stamps and a little woodcutting, but I would still draw. I would cut something out and collage it in. I was wasn’t ready for the whole thing to be woodcut.

When I started The Puerto Rican War, which at this point is a long time ago, I decided I would woodcut the whole thing. I was going to figure out how to do the lettering. And I don’t care how long it takes me. Nobody is waiting around for this book, so it’s going to take however long it’s going to take. And however long it takes, it will be worth it. I would go to comic shows and see people and they’d ask, "what are you up to," and I’d say I’m doing this thing about Puerto Rico. Then next year, "John, what are you working on?" I’m still working on this thing. That’s what happened. If you look at the book, in the beginning of the book the text kind of sucks and by the end it gets better. That is going to happen with anybody that is drawing and making their art. You can see the evolution. My style has changed and I think it’s better. We’re still moving forward with it.

So before The Puerto Rican War you were making short comics.

I’m going to have a book of all my short woodcut comics. I’m actually working on the title cards now for the chapter headers. It’s one- or two-pagers about me walking with my daughter or an argument that I had and shorter comics like that. Like I said, I was working out my look and my style. When I made those woodcut comics, I printed less than 100 of them and I would sell them at comics shows. No one else ever saw them, so now I’m putting them all together. I’m working on that book now, which is no fun because all it is is scanning. Which is the worst! [Laughs] Like everyone else I look at my phone and my computer all day, every day, and I like making woodcuts because I’m not at my computer. I’m told I have a very low tolerance for computer tech things. I’m always the first person to go, I can’t look anymore! But I can woodcut all day.

So right now it’s the boring drudge work of scanning and those kinds of things.

Things to do. I was just scanning today and my pal Gabe Fowler from Desert Island is doing the prep and design work. I had to write a few things so I had to carve some information, but it’s almost there. I wasn’t that excited about it because you don’t get excited about old work, you know, but I was reading it and going, this is pretty good. When I was 30 I put a lot of work into this!

When did you start thinking about The Puerto Rican War?

Ever since I was little. My father was telling me about Puerto Rican history and the various ways Puerto Ricans get ripped off. The fact that nobody knows anything about Puerto Rico except for West Side Story and that it’s a nice place to visit. The fact that the Puerto Rican flag was illegal for years. That they tested bombs there. They used Puerto Ricans as cheap labor. The list goes on and on. I thought, nobody knows about this. A lot of my artwork starts like that. Nobody knows about this and I want to let people know about something. That’s what I started with when I made my comics about teaching in the Bronx. Again I was saying, this needs to be known. That’s where it started and then I started reading and researching for a long time. A lot of times history comics are a little bland because they’re just bullet points. I added in the ghosts of Gandhi and Michael Collins. My thoughts about how these young people would feel about it. These little fictional parts. Somebody once said that we write history to see where we’ve been, and we write fiction to explain how we feel about the history. I don’t know who said that, but I like it and I think about that a lot.

You were thinking about the events and finding a context and what it means.

Definitely. Joe Smith walking down the street doesn’t know two things about Puerto Rico. And I want them to know! This is corny but I think we can be closer together and closer with people if we understand each other. In the same way some religious person would hand out those pamphlets, I want to say, here’s a pamphlet about Puerto Rico so you can understand where we’re coming from. Also, I’m sure if you read the book carefully, it’s no secret how I feel about a violent war. [Pedro Albizu] Campos really believed in Michael Collins and violent revolution and I’m more of a Gandhi person, so I stuck them both in there to converse with each other. My opinions are in there for sure about the best way to go about revolution. I didn’t want to show violence as a glorious thing. There’s a few times where I have a fart while they’re fighting because I just don’t want to have it seem glorious. I don’t want it to feel like violent propaganda.

Earlier you listed things people know about Puerto Rico and I’m sure some readers don’t even know that much.

I’ve gotten quite a few emails and DMs from people telling me, "I didn’t know this, thank you so much." Puerto Ricans have been trying to tell people this. I got invited to do an art show in Puerto Rico at the Institute of Subculture and when I met Alexia, the gallery owner, and we were putting up the show and talking about it, he said, "here in Puerto Rico they don’t teach this in school." That blew my mind! That they don’t teach about this attempted insurrection and how they tried to kill the President and took over two towns, and how the US bombed the town in retaliation. If they don’t teach this in Puerto Rico then it’s taught nowhere! That blew my mind. My Spanish sucks [and] I’ve never lived in Puerto Rico, and everybody there was so nice to me and so supportive. Just calling me brother and giving me hugs. It was wonderful.

When you were thinking about the book and researching it, did you write it all out or have a plan? How did you work?

The first thing I did was write a timeline. I took a long piece of paper and wrote a bullet pointed list of everything that happened and everything that should happen in the book. From that timeline, I took little post-it notes and I wrote notes like, get a picture of what old San Juan looks like, get pictures of 1950 cars, get a picture of some suits. Although what I do is very stylized, I used reference. Once I had that huge list, I would take one part of the list and work on that. You see that I have chapters in the book, and I was only worrying about one chapter at a time. To break it down like that was so much easier. I didn’t think about way off in the future and this part or that part of the book. That made it a bit easier.

Was there a model in mind you that you were thinking about or looking to?

As you can see my references in the book, there’s two books called War Against All Puerto Ricans [Nelson A. Denis; Bold Type Books, 2015] and American Gunfight [Stephen Hunter & John Bainbridge, Jr.; Simon & Schuster, 2005]. In War Against All Puerto Ricans, these guys are experts in fighting. The book American Gunfight was a little more critical of them and [suggests] they didn’t know what they were doing. I think I split the difference of the two. I also talked to Dr. Basilio Serrano, a professor of Puerto Rican studies, who helped me a lot. He would say, you should read this book, and he would say, you’re on the right track. I really didn’t want to be wrong. It did take me a long time and I was just super careful about it.

As you said, your art is very stylized but you were still relying on reference and focusing on these details.

I wanted that-- if there is a Luger that jams up, what does a German Luger look like? Was the style for double breasted suits or skinny suits? Just things like that. And then when the assassins get to America to kill the President, they’ve got to have hats. They’re dressing up because they’re in America. Things like that. I wanted it to be 1950. I wanted the facts to be right, but it also had to fit in my style. [Laughs]

So you drew the book chapter by chapter.

Yes, but I drew the middle chapter and then I drew the beginning chapters. I started in the middle. Somebody said, "why don’t you put this out into the world chapter by chapter?" Well, because I started in the middle. [Laughs] That’s why! The typical comic thing when you put out the chapters as minis in order and then you put out the trade, well, I did it wrong! I started in the middle where I knew what I wanted. The end drove me crazy for a little while.

The book I’m working on now, about the Puerto Rican revolutionary Lolita Lebrón, I know how to end it and where to leave it, but there’s a lot of stuff in the middle I don’t know. [Laughs] I think I overcompensated. The next book, I’m going to know how to end it and not stay up all night for nights and nights.

You might not be able to answer this, but why did German Expressionism speak to you?

Because I can’t be Lynd Ward or Rafael Tufiño. They drew those exact things, and then sat down and seemingly–to me, from what I can gather–carved exactly what they drew. Whereas what I draw and what comes carved at the end are two very different things. I draw a very simple face with two dots and a smily face and some ears and then, as I’m carving, I want to make him look mad so here’s some zig-zags over his eyes, and that looks good. I didn’t draw that first.

I’m not sure why Expressionism. Expressionism is a very loose and it’s very haphazard, which is kind of crazy to think about it because its woodcutting so whatever you do is permanent so you have to be a badass to do it. I’m not as much of a badass as some of those German Expressionists were. I try to be. Especially after doing the text because the text has to be really exact or nobody can read it. Carving the text is very slow. I’m there with my ruler. When it comes to the figures, what’s really fun if you mess up the figure, then you have to save it. Where is this? Where is it going? Because you can’t erase it. I have to save this piece of wood! [Laughs] I have to bring it back. That’s kind of fun. I think for The Puerto Rican War I only threw out four blocks of wood. I put some to the side and would just stare at it for a while. Then I get all grumpy with my daughter because she draws on an iPad and has infinite chances. I’m such an old man grump. “Look at all the chances you have!” [Laughs]

If she doesn’t like a line, it doesn’t matter.

I deserve all the eyeballs she gives me because I’m a very grumpy old man wood-cutting guy versus daughter with iPad. She’ll start and restart something for a half an hour! She’ll just keeping erasing and at the end of the day she won’t have much because she just kept erasing. Incredibly, we get along, but there’s always that joke between us.

You said that you only threw out four blocks of wood, but is that many? Is that few? I don’t even know.

People think I’ve thrown out more. The Puerto Rican War is 96 pages so to only throw out four is pretty good. I think they were mostly because I mixed up the text. Or I carved out some space too much. Other than that, I saved them.

It’s also hard because you’re not drawing something, you’re drawing the negative image of something that will make the print.

It’s a different way of thinking. In some ways it’s better because if I could erase it and do it again, it would probably take me longer. This is what I have and this is what it is. Maybe I should have made this panel bigger and made this go on a little longer, but this piece of wood has been carved down for a couple of days now and I’m not doing it again. This is what I have. Here it is.

You accept that you can’t make a perfect line, but you see that you made a line that works.

Exactly.

It’s getting a little better now. It’s getting tighter with the work I’m working on now. It’s evolved a bit. Hopefully for the better. I still like to not know exactly what I’m doing and trying to get myself out of things just so it looks expressive and loose. I know I’m not Lynd Ward or Rafael Tufiño, so I have to be me.

You need that element of figuring out in the moment.

Oh yeah. Otherwise it looks real sterile. There’s very few artists that look sterile but are still showing a lot of emotion. Moebius is good at that. We’re not all Moebius. He can make something look tight and technical, but he can also give you heart and make you feel something. Whereas Jack Kirby is super-loose, but he’s another magic man that we can’t all be.

When you were starting to do this, especially early on, were you looking at Eric Drooker or Peter Kuper, and people not doing exactly what you’re doing but their own approach and sensibility that drew from Expressionism?

Yeah. Both those guys are great. Peter Kuper in Heavy Metal actually was the first autobiographical comic I ever read. When I met him, that’s the first thing I blurted out. [Laughs] You were the first! He said, "okay." [Laughs] I definitely got a lot of influence from them, too. I’ve definitely tried to copy a little Peter Kuper at some point in my life. He used to be in Heavy Metal in the '80s and I used to look at those old Heavy Metals and flip through it to see if he was in there. I think in trying to look at people and be them and just failing, that’s how people get their own style. They’re trying to be the people they admire and they’re not good at it, so here’s my style now that I’ve tried for a while now.

When I was in college I discovered that printmaking is this thing you can do. Instead of making one painting and selling it to one rich person for millions of dollars, you could make a lot of them and give them to a lot of people, my teenage brain thought. I could make a lot of things and give it to everybody! The most socialist thing. That was very appealing to me.

I keep coming back to the idea that with a woodcut you’re starting with black and carving out the image.

When I teach printmaking workshops, I take the black image, and I draw for everybody and say, now you want to keep everything - except what you drew! I can see them working it out in their minds, "what?!" But basically you get that concept first, and it’s funny to see people work that out in their brains and even come back and ask me again, "so this is what I drew, but I don’t carve it?"

It’s a different way of thinking.

Like everything else, the artist is just trying to find their tools. Watercolor works great for some and Rapidographs work great for some, but for me, when I started working like this, something just clicked. It just fits for how I’m thinking and what I want to do.

There’s that line about how you picture the image in a block or marble, and chip away everything extraneous to get to the image.

Get rid of everything not an elephant, as they say.

And with a woodcut you picture an elephant, and you’re not carving out an elephant - you’re carving out everything not an elephant.

Sometimes I do over a carve and it looked better before. I look at someone like Mike Mignola and he has a great sensibility as far as keeping it simple. But it’s tricky because it’s not simple! [Laughs]

Many people have said that Hellboy looks easy to draw, but he’s not at all.

Yeah, I got that Artist's Edition last week and I could see what he was doing. Not that I can do it! [Laughs] The glory of all the blacks.

As you’re putting together a book of earlier work, especially after The Puerto Rican War, which was such a big project, can you see the way that your work has changed or your approach and thinking has changed?

I take more chances now. I’m more confident now. My lettering is better. I was very ambitious, so I was really putting in the hours. I have a few things that are in color that I’m going to spend the big bucks and keep it in color. I have one piece that I had a block and I jigsawed it into puzzle pieces, inked them all different colors and put it back together. I have to explain that to people so when they see it, they really appreciate how it was made. When my daughter was first born she would take a nap and I would sit and work. She would wake up and I’d be with her and then when she’d take a nap, I’d sit and work. But again, I’m just better at it now. Sometimes the topics I did were just a little fun thing off the top of my head, but those aren’t always my best work. I think my best ones are talking about the teaching system, The Puerto Rican War, my new one - just to name a few off the top of my head. The small fun [topics] like, "here I am, taking a walk with my daughter," might just be fun for me, so I try to stay away from them even though I get excited about it.

Those kinds of short little things are when you can experiment and play around. They may not be the best pieces, but they’re often important pieces.

I think a lot of people are going to see that I’m working things out. I just did a podcast with Thick Lines and we talked about Barry Windsor-Smith when he used to do Conan. He was fantastic, but he was working it out. We were talking about that. I think it’s the same for me–only not fantastic–but you can tell I’m working it out. Like this piece behind me I made more than 10 years ago, it was super-ambitious. It’s got the most text I ever did. It's about two soldiers arguing about communism versus capitalism, and then they get shot by friendly fire at the end as they’re arguing. A “fun” work! [Laughs]

You also made a piece for the MoMA Magazine recently. How did that happen?

First of all, I was very surprised and very proud of myself, that I self-published The Puerto Rican War and it made it all the way to somebody at the MoMA who saw it and said, "let me write to this guy." That’s really good for a self-published book by a guy with an Instagram account. So I said, sure. They had a Frédéric Bruly Bouabré exhibit and they meant for me to walk around and see the museum and make a comic. They were like, "what do you think of this exhibit? Can you look at it and give us your thoughts?" I had to look at it first before I said yes or no, because if I didn’t have anything to say, or I didn’t like it, I didn’t want to make it. Like I can’t fake something. I’m not good at that. I went there and I actually liked it. He invented his own language. He transcribed his own dying language and invented pictures for it. He did parts of African history. I could see why they want me to do this. He was my kind of guy. But I still didn’t know what to make about it until I just said, I’m going to look at it and write down my thoughts, and that’s the comic. They want a Mejias comic, that’s what they’re going to get. So I sat in the room for a while and I wrote a list of all my thoughts. I brought the list home and it became a comic.

It was this very nice five-page personal response to this very personal body of work.

And again, I had to build up my confidence to say: whatever I think about it is going to be my opinion. They asked for my sense of it, so I can’t go wrong, right? [Laughs] The way that he made his opinion about the world and nature and history, I’ll do that about him.

They just came across your work and reached out?

Being Mr. Cool, I didn’t say, how did you find me?! [Laughs] I just said, sure, I can do that. Of course you want me to do this. [Laughs] Everybody else they’ve ever had has been published by Drawn & Quarterly, Fantagraphics, Pantheon. Big publishing houses. Not a guy making and publishing books solo.

The Puerto Rican War is part of an exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and they’re using my artwork for the banner ad online, and once again I was like, sure, you can do that. But I keep thinking: what?! How did you find me?! But that’ll be fun to see the exhibit. And there’s going to be other books around Latin American art. I don’t know what they are, but I guess I’ll find out.

But people who go on your website will find that The Puerto Rican War is not just a book, but a play.

There is a play! [Laughs] I like how it’s a play. I always call it a performance.

We can call it whatever you want.

I’m going to start calling it a play. One thing I never call it is a puppet show. People think it’s juvenile and it’s for kids. But to call it a “Performance” with a capital P makes it sound fine art.

It’s the same as people saying “graphic novels” instead of “comics”. It’s my third puppet show or performance. When I was working on my master's I really wanted to make a puppet show, and so I took it upon myself to create an independent study and I made one about teaching. It was just woodcuts on a stick. My second one was a shadow puppet performance about the worries of kids. I asked kids what they were worried about - and I told them they wouldn’t get in trouble if they told me. I had two under my belt, and so for this one I looked into kabuki theater and marionettes and puppets. It’s basically a promotion for the book because, as I tell everybody, I don’t like book talks. I never go to a book talk. And I love books! But I sit there and the guy shows something on the screen and talks about it, I just think that’s boring. I want to go out and talk about my book, but I don’t want to do a book talk, so: puppet show! And of course my hope is that the art nerds who might not go to a book talk will go to a performance or a puppet show and see some marionettes.

It’s been pretty successful. It’s about 20 minutes long and tells the story of The Puerto Rican War. It has a theater that I made out of PVC pipes so I can roll it up and put it together. It has a pre-recorded soundtrack that I can push play on. It takes myself and three other people to perform it. It used to be my mom and my sister. They did it once and then said, "you want to keep doing this? We’re not going to keep doing this!" [Laughs] So at this point The Puerto Rican War is performed by a Scottish person, a Japanese person, and myself. [Laughs] Another thing is that it’s just nice to perform and get out and away from my desk. I think that most cartoonists like sitting by themselves and not talking to anyone and drawing all day. You have to like that to a certain extent, but I do like to get out in front of people and perform with my friends.

And you’re wearing a mask and performing puppets, so you’re not standing in front of a crowd talking about yourself.

Exactly! I used to play in bands, and before we would play I would forget all the notes. [Laughs] I don’t have that now. I have a mask or I’m behind the curtain, so you don’t have to be a total outgoing person. There is a little bit of choreography where it’s my half-assed modern dance moves [Laughs] but I love doing it. I love it. I’ve been doing other things, but there’s going to be more performances coming.

My friend who performs it with me makes comics as well, and he just made a shadow puppet show and I said, come with me and next time we do it, we’ll have a double bill. We’ll do your shadow puppet show and we’ll do The Puerto Rican War. Let’s start a thing where people do performances about their comics!

That would be exciting. And different from a slideshow book talk.

I don’t want to talk bad about people because I love comics, but I don’t like the slideshow. I’ve never been excited by it. Maybe I’ll be excited for David Sedaris, but that’s one guy out of like a million that I would go see.

So you’re acting out the book?

We’re acting out the book, but it’s a little bit abridged. The book is already pretty abridged, but it only takes about half an hour. Much like kabuki theater, everyone comes out in a mask and half-poses. And then during the battle, a bunch of marionettes come down and there’s this great avant-garde puppet music. And then during the bombing there’s a liquid light show, Frank Zappa-style. Truman has a puppet of a plane, and he’s bombing the town with the liquid light show. That represents the bombing. The narration is happening and explaining what’s going on throughout.

So the play is something you do here and there.

It’s hard to find a space for it. If you’re in a band, everybody knows spaces where you can play for like half an hour, but the world isn’t really made for traveling puppet shows. You have to ask, and people have to see what it is. I’ve performed it at three art galleries and two different community gardens and a couple bookstores. I did it at a Desert Island event. Again, some people go, "what is that?" But other people are like, "yeah!" So you have to find your audience.

The worst part of it is traveling because it has to all fit in a car. While I’m performing, I think we need more stuff, but when I’m home organizing it into boxes I think I need less stuff, this is way too much. I live alone most of the time, so I have most of the control of the home. My daughter comes to stay with me and I clean up the puppets for her. [Laughs] I also have to emphasize that I don’t really know what I’m doing. I’ve never taken a puppeteering class. Like woodcutting, the learning is in the doing. A college asked me to be a guest and do a puppeteering workshop and I was like, um, okay. [Laughs] Fake it 'till you make it! Or maybe I’m just discouraging myself.

Imposter syndrome.

It’s a bit of imposter syndrome. But seriously, I’ve never taken a class. When I first started making puppets, they would fall apart. But yeah, imposter syndrome is a good way of putting it. If you see that movie Being John Malkovich and how complicated the marionettes are, my puppets don’t do that. [Laughs] I rely on it being charming more than anything else. Not technically amazing, but charming. Which in my opinion goes a long way. So I’ll do another performance, but I have no idea when.

So more exhibitions, another book, more performances. You’re keeping busy.

I’m miserable if I’m not busy. I don’t know what to do with myself if I’m not really busy. I just finished a project–well, I thought I finished everything for this book, but I didn’t–and I had nothing to do that day so I told my friend we were going to start a band. I said we’re only going to play twice and break up - but we’re still going to do it. [Laughs] I’m more excited about making masks and making posters than I am about making music, but I like to be busy. It’s a worrisome feeling when I’m not. Do you feel that way sometimes?

Oh yeah.

So you know. If I have a book that comes out or I’ve finished a mural, the next day it’s like, what do I do with myself? I’m jumping out of my skin and I need somebody to call me and tell me to do something.

Some people have talked about the postpartum nature of finishing a big project.

Good. I’m glad to know I’m not alone in that. So you just keep it going. I just think of the next thing before the thing I’m working on is done. Then I can move onto the next thing. I’m also doing a mural, but that’s not until the spring. On 187th Street there’s a series of 130 steps. Sort of like in the Joker movie. I’m going to do a mural on the front side of all the steps. It’s sponsored by Mount Sinai Hospital. I’m excited about that, but it’s further off in the distance so I have some time to worry about it.

You’ve made a few murals, do I have that right?

I’ve been teaching kids and we do a mural almost every year, even if it’s just a tiny six-foot thing. Then I went to Puerto Rico and did a 40-foot mural and I got the bug! Somebody who saw the mural in Puerto Rico said I should try out for this thing. They had a few people who pitched and I guess they liked my pitch.

So you have a lot of things happening.

Yeah, I’m doing good. I turned 50 in September and I want to be an awesome 50-year old that does a million things! It’s like turning a corner into something new. I want to be a 50-year old who has many things going on.