My brush with comic book celebrity came when I was 17 years old. We were a month into our AP English class at a high school outside of Portland, OR, when our teacher departed on paternity leave for the remainder of the year, leaving us in the hands of a capable long-term substitute, one Ms. Wagner. Periodically throughout the following class term, Ms. Wagner would drop references to her husband “the comic artist.” Portland being a comics town, I thought little of it, until, during the final week of class, she finally added the first name “Matt” to that description, and the penny in my brain very belatedly dropped.

Perhaps it was for the best I hadn’t known, because the knowledge of being one step removed from Matt Wagner would have been enough to leave me distractedly starstruck in those days. That this was true even despite the fact that I had largely fallen away from monthly comics—these were my years of pretentiously reading Chris Ware in public—testifies to the peculiar place that Wagner has always occupied in the comics firmament. Neither a creature of the mainstream nor a product of the underground, he has remained defiantly in the good graces of both. This owes much to his skill as a cartoonist: his linework, balanced on the liminal edge between Japanese-influenced exaggeration and shadowed American noir, have at this point evolved into something akin to a harder-edged Will Eisner (an artist to whom Wagner openly credits a great deal).

Yet as popular-skewed as his storytelling sensibilities may be, Wagner has largely avoided the temptations of long-term work-for-hire employment: some Batman stories here, a stint writing Zorro there, and a highly-regarded tenure as the co-writer of DC’s Sandman Mystery Theatre, but nothing in the manner of, say, Frank Miller’s years on Daredevil. Instead, Wagner’s great passion has been his two creator-owned titles, the Arthurian modernization Mage, and the decades-long, multigenerational epic-in-progress Grendel. It’s fair to say that Wagner’s tastes aren’t so much for Marvel’s and DC’s stock in trade of superheroes, as for the pulpy elements that inspired them. Reading Grendel especially is like journeying through an alternate vision of how dime store crime comics, science fiction anthologies and Hollywood B-movies might have evolved into another comic industry entirely - one thoroughly lacking in the crowd-pleasing niceties and comfortable illusions of change that define the one we got.

What he is, in fact, is a lingering vestige of the 1980s heyday of mainstream independent comics: the decade when both Mage and Grendel debuted at the now-defunct Comico. Those days, coming in the wake of the breakout success of Eastman and Laird and their Turtles, were a time when comic publishers imagined doing what Marvel and DC had once done, and capturing the readership they had once held, albeit with the creative freedom and lack of corporate oversight that revealed their gritty roots. Those utopian years are behind us, but Wagner survives, a lone reminder that mainstream isn’t synonymous with anodyne, and popular isn’t the same as compromised.

This November, Wagner is returning to his earliest roots, augmenting (not to say giving the George Lucas treatment) to one of the earliest Grendel stories, Devil by the Deed, with a Master’s Edition that augments and re-contextualizes the original narrative in light of its creator’s 40 odd years of additional mythology and biographical detail. Wagner spoke to me from his home outside of Portland to talk about returning once more to his signature creation, tying off the long-running trilogy of Mage, and the road that’s taken him here.

-Zach Rabiroff

ZACH RABIROFF: You’re in Portland now, but where are you from originally?

MATT WAGNER: Kind of central Pennsylvania, nowhere anybody would've ever heard of. The closest thing of note was State College, which is the main campus of Penn State. I lived about 25 minutes away from there, maybe 30 minutes out in Amish country. My parents had been married a long time, tried to have kids; never worked. They built a retirement home with a barn and a stable. My dad was a horse fan, he wanted to get a horse. And they moved in, and three months later [my mom] was pregnant. [Laughs]

What did your parents do?

My mom was, in her early days, an English teacher. And later I married an English teacher…

I’m sure we can do some psychological analysis of that.

I also married my editor, Diana Schutz's, sister. My dad worked for a synthetic fibers corporation for years. He was in World War II, and following that, he got a job with this corporation. He was there his entire professional life, pretty much. I mentioned my mom had been an English teacher, so she was always really strong about encouraging me to read, and I became a voracious reader as a result of her.

Were you reading comics at the time as well?

Yes, absolutely. A lot. Unlike a lot of English teachers of her generation, my mom didn't mind that I was reading comics so long as I was reading; you know, she thought I'd grow out of them. [Laughs] When I was growing up, they had a childhood memories scrapbook sort of thing. And on the back of the grade school years, it said what I want to be when I grow up. And in second grade I wrote “astronaut,” and that was the year they landed on the moon, so every kid wanted to be an astronaut. Then every single other year, I wrote comic book writer. Now, I put comic book writer because at that point I just assumed whoever wrote them also drew them.

A utopian vision.

Right, right. I’m just one of the extremely lucky few who got to grow up and do what he wanted when he was a tiny, little kid, you know?

Tell me about the origins of Grendel. Where did this idea come from?

I read a book when I was about 13 called Grendel by an author named John Gardner that told the story of Beowulf and Grendel, but from the monster's point of view; it was sympathetic to the monster. And that kind of blew my mind. And then when I was in high school, I discovered the works of Michael Moorcock, specifically the Elric saga. That was my first experience with an antihero of that sort. Because you were very much entranced with Elric, and very much on his side. And yet he did a whole lot of horrible things, and ended up killing almost everybody who was ever dear to him, and almost everything he attempts to do doesn’t work out. So I would say those two factors really influenced me a lot in the direction I went with my first creation.

Similarly, I had a book that was popular at the time called The World Encyclopedia of Comics, by a fella named Maurice Horn: big, thick reference tome. And I would pore through that and learn a lot about international comics that I had no access to. And I learned about the Italian characters Diabolik and Kriminal. And they were both kind of gentlemen criminals that had a code of honor. They were still ruthless to their enemies, but had some sort of code of conduct; certain lines they would not cross. All that kind of culminated in me trying to come up with a storyline wherein our main character was the villain, but he was handsome, and suave, and debonair, and the good guy was ugly and brutal and savage. So that was the basis for it. Of course, in no way did I imagine it would ever leap beyond its initial [concept] into this century-spanning epic. I kind of was making it up as I went along. I almost compare it to a jazz riff, where you pick up a note, and you just kind of go this direction and then that direction.

When did the Hunter Rose character [the original Grendel antihero] really crystalize for you?

Around '79, '80, I was in college-- I had done two years of college at a liberal arts university in Virginia, a place called James Madison University, and then I transferred to an art school in Philadelphia, the Philadelphia College of Art. And it was there that I met the guys that ultimately formed Comico, my first publishing company. And they gave me the opportunity to come up with a character in a book, in black & white. And unfortunately for us, this was just before the black & white boom of the '80s, where every black & white book just sold out the wazoo. We kind of missed that by about three years. So I set about creating this character, and, you know, I will fully admit the first efforts were kind of crude.

That was the aborted three-issue Grendel series [i.e., an ongoing series cancelled after three issues, 1983-84]?

Yes, and the short story in [Comico's early house anthology] Primer, which was the first appearance of Grendel [Primer #2, 1982]. And so, when you say “aborted,” we discovered that the black & white books just weren't selling, and we were going to have to go to color. Comico had struck a deal with Chuck Dixon-- and this was before his rise to fame working for DC. And he had a book with his then-wife, who was the artist Judith Hunt. It was called Evangeline; it was about a killer nun in the future, an assassin for the Vatican. And in those days—I don't know if this is still true or not—but in those days, it behooved any publisher to print two books at once, because the printing presses were X wide, and they could fit two runs side by side. So you were basically paying the same for two books to get printed as you would for one book to get printed.

So they needed another color book, and of the four books they had originally done in black & white, Grendel had garnered the most positive reaction. So they offered me a chance to develop something, and that turned into Mage; I decided to go a completely different direction. Then after I'd been doing Mage for about five or six issues, I started to get responses from people: “Hey, whatever happened to Grendel, you just kind of quit that mid-stream, you know?” And realized there was interest in finding out how the story wrapped up, because we kind of started at the end with Grendel dying.

So that's when I reworked it into being this backup feature in the back of Mage. It was four pages every issue. And as a result of that limited space I had to work with, that's how I struck upon the idea of doing it not as traditional pane-to-panel comics with word balloons and captions, but almost as an illustrated text. So we had blocks of floating text on these very designy pages. And in that fashion, I could squeeze more story into four pages than I would've been able to just with traditional panel-to-panel continuity.

It's a really interesting shift from the initial three issues you had done, not only in storytelling style, but in art. Those first three issues have an interesting combination of rounded, almost cartoonish forms, and noir-influenced very heavy blacks and shadows. How much of that was deliberate, and how much was just your early style?

It was deliberate in that I had just discovered anime, and anime was kind of a rarity at that point. Right. There weren't many examples of it available here in the States. So it seemed intriguing to me, this style of big feet, and big eyes, and the little mouth, and I was kind of taking my cues from that. But at the same time, yeah, I was also influenced by noir comics. Frank Miller was in the thick of his upward trajectory at that point, and his style was really prevalent all over Marvel comics. So there was a huge, huge switch from those [issues] to what ended up becoming Devil by the Deed in the back of Mage. And part of that was, again, as I said, the limitations of space I had to work with. But also I was just growing up creatively. There's an old adage in comics that everybody has a hundred pages of comic art that they have to poop out first before they get to anything that looks pretty good. And I was reaching that hundred page mark, finally.

So in some ways a boon that you had to take that pause before you returned to the character.

Most absolutely. And that's been true with a lot of my career. You know, the sequels to Mage got delayed due to Comico’s bankruptcy, and that sort of stuff. And I later realized what a benefit that was: it gave me more time to reflect on my life, since Mage became an allegory of my own life. So, you know, it just worked out.

So what did you draw from when you conceptualized the very illustrative style you adopted for Devil by the Deed?

I said I had discovered anime. In the interim, I had discovered the works of the Art Deco movement, and Alphonse Mucha, and that kind of thing.

I was going to mention Mucha. I can definitely see the influence.

It's not as severe Mucha as you see Adam Hughes using sometimes in some of his illustrations, which he's really good at. But you could tell the influence is there. I'm digesting it, and distilling it into my own version: a simpler version, because I'm doing continuity as opposed to just singular illustrations. You can't get that sophisticated on every page.

It also looks like you’re drawing from stained glass window artwork, or maybe illuminated manuscripts.

Yep, yep. All of that. And in his original introduction to the collection, the first collected edition, Alan Moore compared it to pinball art. I hadn't considered that, but that works.

The Grendel character is a marked contrast to what you were doing with Mage at the time, just in terms of the general mood and the outlook of the characters.

I always say that Mage is about facing up to life and growing up, whether you want to or not. And Grendel is about great aptitude that atrophies and never comes to fruition. And those are two diametrically opposed outlooks. I just found it very creatively fulfilling to be able to play with both of those concepts, and not get locked into one mindset, because I don't feel like I have one mindset about life. You know, I believe in heroism. I believe in doing the right thing. But I'm also incredibly cynical when I look at the world around me and realize what most of the people in power are, you know? So I was just glad that I didn't get pegged into one way of looking at the world creatively.

Interesting, though, that you knew from the outset of the Hunter Rose story that you were going to kill him at the end, because you put it right there in that first book.

That was probably inspired by Arthurian [storytelling]. One of the most famous accounts of King Arthur is Le Morte D’Arthur, this big compendium written by… oh, God, the author’s name escapes me now. The author was in prison when he wrote it.

Thomas Malory?

Mallory, yes. But of course that means “the death of Arthur.” That seemed intriguing to me. Again, I was just always looking for different ways to tell stories. And at that point in comics you had Frank [Miller] doing stuff, you had Alan Moore doing stuff, but stuff had gotten pretty tired and pretty by the numbers, you know? So we were always just looking for different ways to tell things. And starting a story with the main character, this kind of all-powerful villain, on death's door, just seemed a very intriguing thing to me.

Did you have any notion that you were going to come back to the character after that?

None at all. Comico approached me later saying, “Look, we would really like you to continue Grendel as an ongoing monthly.” And I was like, “Well, I just killed him. So that's going to be kind of hard.” [Laughs] So here again, drawing inspiration from the things that I liked when I was young, the comic strip The Phantom by Lee Falk: in the comic strip that Phantom was, I think, the 32nd Phantom; it was a generational character. The father handed on the role to the son down through generations fighting piracy and corruption. And I will admit the influence of Michael Moorcock is here as well - the fact that in his Eternal Champion cycle, you can have a character be in different realities, interpreted as different versions of the same persona.

So I thought, well, why does it have to be Hunter Rose? Can I come up with another version of Grendel and just continue it like that? And then it struck me: why don't I just keep doing that? Why don't I make that a major motif of the series as a whole? And when I was asked to do a monthly comic, my thought was, the only way that's going to remain interesting for the readers is if it remains interesting for me. And I'm going to have-- I don't want to say fickle, that's not the right word. I know how hungry I am for change in my narrative. So I wanted to just keep changing things over and over again.

At the same time, another change I was looking for was the fact that I had just finished Mage. I had just finished Grendel: Devil by the Deed. And I was getting a lot of props, lots of people patting me on the back and telling me, “Hey, man, you're doing great. You're doing everything exactly right.” And luckily, I was only 25 years old, and I was smart enough to be suspicious of that. So I decided to step back from the art and try something I had never done, which was to write for other artists, and that would force me to see things in a different fashion.

I discovered the work of the Pander Brothers when I was on the Mage tour in 1985, which was a cross country tour with a group of buddies. I got Comico to rent this tricked-out van, and we traveled all the way around the country. We were on the road two and a half months, and we did 27 signing appearances. And that really served to bump Mage up into the next level of awareness in the comic book stores. It also gave me this huge education about the comic book market. I got to interact with retailers of all different levels, and fans of all different kinds.

Beginning with that second story arc that the Pander Brothers drew [Grendel (color series) #1-12, 1986-87], you started building out the larger generational mythology of Grendel, but periodically you keep coming back to this initial character of Hunter Rose. Why is that?

Well, I'd say it's a combination of crass commercialism and a familiar creative well that is deep, and dark, and doesn't seem to have a bottom. [The upcoming Devil by the Deed: Master’s Edition] was a bit of crass commercialism combined with a creative challenge. It was meant to both support and piggyback off the higher visibility of the Netflix [Grendel] show. And, of course, Netflix canceled it.

As Netflix does.

The whole series is filmed. I have it all on DVD.

Not to derail this conversation, but do you have any ability to sell it to another network?

We tried; nobody bit. The first episode is completely finished. The other seven are all put together in a very watchable format, but there's still plenty of post-production stuff that needs to be done on those. But yeah, it’s crushing, believe me.

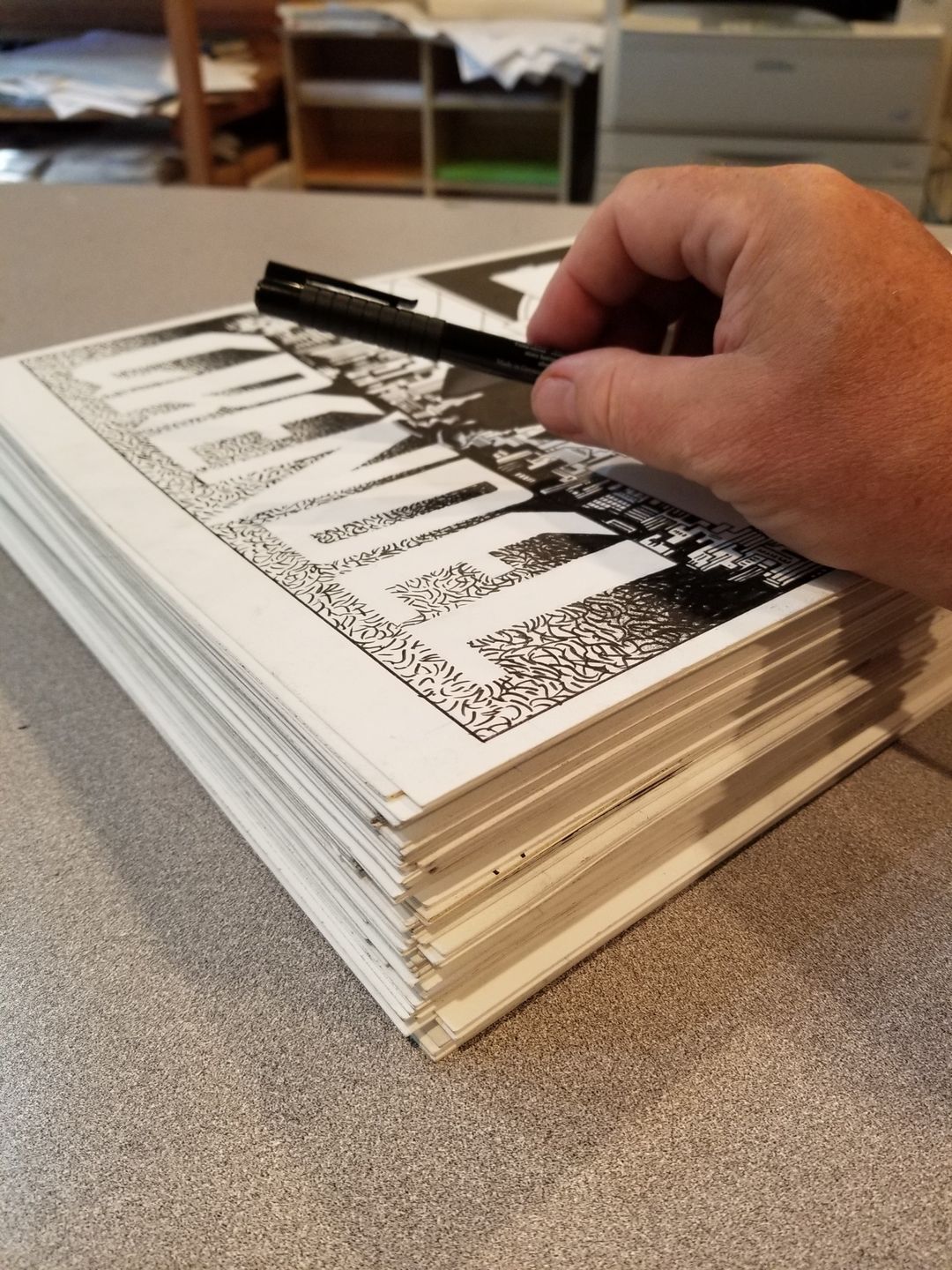

But when it was still up and running, and it looked like we were going to get this much greater visibility for the character, I approached Dark Horse and said, “Look, the first version of Devil by the Deed, considering how iconic it became, is only 37 pages long. And I drew it when I was 24. Let me come back and just completely redo it. It'll be the same story. It'll be informed by the other stories of Hunter Rose I have done since then. But it'll be drawn by me now at 60, in a much different stage of my artistic career and capacities. And it won't be 37 pages, it will be 121 pages. And I'm thrilled with it. I'm totally proud of it. My son, who is my regular colorist, Brennan Wagner, he colored it. It’s in the black, white and red palette that has kind of become Hunter Rose’s motif over the years. But I saw that as a challenge to go back to my first steps, reinterpret them, rediscover part of who I was then, and yet bring all the various skills and influences and talent that I've developed over 40 plus years of doing this every day, and weave something entirely new.

All of the Grendel stories have an unusual willingness to traffic in unhappy endings, which is out of the ordinary for comic heroes, I would say.

I would say, yeah, it just doesn’t work out in Grendel. [Laughs]

Where is that coming from, do you think?

Look at society. Look at history. I'm surprised humanity's lasted this long, you know? I can look around and I see acts of great charity, and acts of great creativity and altruism. And there's acts of great barbarism and cruelty: I mean, my God, the way this country's divided now, the MAGA crowd doesn't seem to have any philosophy other than just cruelty. They don’t seem to have any political aspirations or any policies in mind. It's just the other guys. And a movement can't sustain itself on that. That’s just sheer nihilism, you know?

I guess if we want to get speculative about it, we could say the cynicism of Grendel starts with Reagan, and evolves into what we’ve seen the country turn into by the time we get to Trump.

Yep, yep.

It’s interesting to me, because Grendel seems to exist right on the nexus of the comic world as, on one hand, a highly populist, commercial book, but also something that defies all the clichés of comic book commercialism.

It helps that I have Mage, which is much more hopeful, and much more down to earth and humane. So I get to unleash my anarchy-ridden punk rock self via Grendel. I mean, certainly, I don't want to say I don't want readers—I want readers—but I don't want my readers to ever control me. I'm going to do what I want. It's why I've really done such limited stints of working with the big publishers. And every time I've worked with the big publishers, it's always been in conjunction with an editor that respected me enough, and knew to just step back and keep their hands off me. You know, Karen Berger when I was doing Sandman Mystery Theatre, Bob Schreck when I was doing some Batman stuff. Archie Goodwin to go back a little further when I did [the Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight story] “Faces.” But I just can't stomach having some editor call and tell me how to improve something narratively. It's like, that's not why you hired me. You hired me because I know what I'm doing, you know?

So what I'm doing is always trying to keep my readers off balance. If they know what to expect, then I'm just a can of Campbell’s Soup. I have to always be unexpected as a storyteller. The best stories are always going to lead you somewhere that you didn't expect. If they don’t, then they're as tired as most of the major religions are, you know? So it's a combination of deliberate thumbing of the nose at traditionalism, but also just the way I'm built. That’s what I want out of the stuff I read. I want it to surprise me, and I want to take me places that I didn't expect. So I like to try and mirror that in my own creations.

And part of that seems to be a really freewheeling influence from different kinds of pulp genres.

Yeah, I’m a real genre-snatcher. I just stick it all in a blender and let it roll.

You’ve gone from pulp crime, to mystical and magical, and then ultimately to science fiction in Devil’s Odyssey [Dark Horse, 2019-21]. Did it ever feel like a risk to you?

Well, yeah, I always wanted it to feel like a risk, you know? The great thing about being an artist is to be able to venture into the unknown. The most recent thing I did, Devil’s Odyssey, I had returned to Grendel Prime after doing the third Mage series [The Hero Denied, Image, 2017-19]. And when I came back to it, I thought I was feeling a little tired, like I've done this. So, what can I do? I'm going to send Grendel into outer space. [Laughs] And, in the follow-up series, Devil’s Crucible, which I'm working on now, he comes back to Earth and everything's changed. I didn't picture that when I even started Devil's Odyssey. It was only about halfway through that I realized where I wanted to end up. To me, that's just the joy of doing what I do. Stuff just occurs to me all the time - ideas that, when they come to me, they seem so natural. Like, snap: that's it, man.

It sounds like a lot of this is just allowing yourself to generate this universe as you go, and that there’s not really a grand plan behind it all.

Oh, there’s definitely not. That's why I love doing what I do and the way I do it, which is to keep it kind of loose and open and free. Like you said, anything can influence me, and I'll take it and run with it.

Which has got to be liberating, but also terrifying, I would think.

Yeah, you’re right. That's what makes it exciting. I try to tell people that there's nothing for a young creative more terrifying than the blank page. You sit down, you're like, what do I do? And you're judging yourself so ferociously, and you’ve got to get past that, you know? But at the same time, I assure people that even at my stage—and I've been in this biz a long time, I've produced a ton of work—every time I sit down at the white page, there's that slight flicker of fear in the back of my head that says, “Is it going to work this time? Let's see.”

Going back to this new edition of Devil by the Deed, you mentioned the change you made to the colors, which are a pretty striking alteration from the original version, which were in very much the same color tones and palette as Mage. And now you’ve gone to this red, white and black color coding, as you say, for Hunter Rose. What motivated that?

Devil by the Deed has been colored three times, with three different approaches. The first time [1985-86], I colored it myself in the now-completely obsolete and antiquated technique known as "bluelining," which was a big thing back in the '80s. Dark Knight Returns was colored that way. What that amounted to was that you would create a blueprint image on whatever paper stock you wanted to work on. And then you had the linework on a piece of acetate that flapped down, so you colored the parts that needed to be colored underneath. And then they would scan the two separately and marry them together. So I had colored that, and that's why, as you said, it bore a similarity to Mage, because I was coloring that at the same time. I wasn't that sophisticated yet as an artist, you know, I just kind of did what I knew.

Years later, when the book ended up at Dark Horse, we were starting to get everything back into print. We did another version [1993] that was colored by Bernie Mireault using a much brighter color palette. Then after we had done Grendel: Red, White, & Black [a 2002 various artists anthology series], we put it back into print again [2007], and we had it recolored as black, white and red, because by that point, all the Hunter Rose stuff had started to become black, white and red, and it just seemed to fit his persona. You know, that noir aspect you were talking about, with an accent color. And of course, it’s a dangerous accent color. So it just really fit to continue that for the Master’s Edition.

Now, the black & white art has quite a bit of rendering by me on it in tone. So I was doing a lot of ink wash application, and some black colored pencil, and even a bit of black airbrush here and there. And then my son took that and kind of went to town adding his layers of color on top of that.

And Brennan’s been working on your stuff for some time now. How has that been working out for both of you?

He grew up in my studio, basically, so we kind of speak the same creative language. There's not a lot of butting heads-- a little bit, because it’s a father and son relationship, you know? [Laughs] He knew he wanted to do something creative coming up through high school. I never particularly pushed him towards comics. He just kind of organically settled into comics on his own, and specifically coloring, because he could get a gig. He is now branching off into a whole new aspect as a co-creator of a new series that Dark Horse is publishing. He's co-writing it and coloring, it's called Saint John. I've read the first issue [published September 13], and I’ve got to say objectively, it's great.

We’ve got a totally out-of-the-blue gig right now. Have you ever heard of The Last Podcast on the Left? I became a fan because the main guy, Marcus [Parks], he and his wife do a podcast called No Dogs in Space, which is a deep dive into all my favorite bands: the New York Dolls, the Ramones, the Velvet Underground, the Replacements, the Damned. So I actually wrote them a fan letter, and Marcus told me they actually do a comic book with Z2 called The Last Comic Book on the Left. And they said, “Would you be interested in teaming up on a story about Sid & Nancy?” And I was like, “Yeah, that sounds great.” So I’m drawing that now. It’s written by Marcus, and I’ve only ever drawn a handful of stories over my career for other writers. It’s always kind of intriguing when I do. Brennan’s coloring that too, and it doesn’t look like any of the stuff he’s coloring for me otherwise.

It seems like a lot of thought has gone into the color theory behind the whole Grendel saga: you have this black, white and red coloring for Hunter Rose, and then the palette gradually builds out over the generations, so that by the time you get to Grendel Prime you’re working with a wild spectrum of colors for the sci-fi setting. Was that a deliberate choice?

Again, yes, deliberate, but not premeditated. We get there just because we got there, you know? It's just kind of doing what feels right in the moment. But color's always been enormously important to me. When I was doing Mage, I was writing, drawing and coloring it, and then it became evident I was not going to be able to keep doing all three of those. And rather than give up the color to a colorist, I chose to bring on an inker, which was Sam Kieth. And he started with issue #6 so that I could maintain coloring the book. And of course, it was very painterly color at that point, so it was a bit time-consumptive.

Outside of just colors, how would you describe your artistic evolution over the course of this project?

I think you can see that best in Mage, as an example of how I've kind of evolved. Because when you look at all three of the Mage series—The Hero Discovered, The Hero Defined, The Hero Denied—the second series was done, I want to say 11 or 12 years after the first one. The third one was done 18 years after that one. And when you look at it, it's very evident it's the same guy at three different stages of his life, and three different stages of his approach to his art.

I think at this point in my career, you know, I'm-- I'll be 62 here in a couple of months. I've kind of settled into a familiar style. But I still try and mix it up. The story that I'm doing right now doesn't really look like Grendel. It's incredibly grungy. Lots of sex and drugs. And people have asked me, why is there so much sex and violence in your work? And my answer is because drama is about change, and things have to change for drama to be intriguing. And sex and violence are the agents of change.

Do you think that’s one reason you haven’t chased after a lot of the more mainstream publishing opportunities? You’ve done a little bit of work for DC and others, but you haven’t done, say, a big run on Batman.

No, no. But at the same time, when I go do those things, I understand that [there are limits]. I don't want to show Batman's dick. That's just not where that belongs. I like to push the envelope when I'm working with those characters, but within the [limits] that still make them stay those characters, and that kind of narrative. And so far as working on those other characters, I kind of look at it as a band doing cover versions of the stuff that meant something to them when they were coming up, you know?

What tools are you using to draw with these days?

I mainly use my Faber-Castells: they’re called Pitt Artist Pens. And I have what’s known as the bullet nib. They come in a fine and medium brush, the ink’s color-fast and waterproof. It's nice to be able to just use a pen and not have to dip in anything.

How long has that been your pen of choice?

Oh, probably 10 years now. Maybe a little longer even.

And how does it compare to the way you were working back when you started out, around the time of the first Grendel stories?

So, I didn't ink Devil by the Deed, that was Rich Rankin. But I was using more traditional media at that point, mainly because that's all we knew. The markers at the time, anything that would resemble this, had ink in them that would fade real fast. So I mainly used a quill brush. I really appreciated the fact that you could get so much variety out of one tool: you could get a very fine line, you could get a thick line, you could get a rough line. I drew a lot of inspiration from Will Eisner: his run on The Spirit that was reprinted by Warren in the '70s had a real big influence on me as well.

So in your inking, at least, you seem to be remaining firmly analog.

Oh, yeah, yeah. I'm too old to learn that new trick. [Laughs] Plus, I just like the organic quality of touching the paper, and seeing it come to life at the very tip of my fingers, as opposed to on a screen. Everything's on a screen these days.

Do you ever see yourself coming back to the character of Hunter Rose again? Or does this feel like it to you?

You know, I say it every time: this is probably it. But, the problem is he had such a short lifespan; he was like a fiery comet that burned itself out. But somehow I manage to keep squeezing in new stories. I don't know. We'll see. I'd never say never. I do feel like I'm done with Mage. I finished Mage, I stuck the landing. I have so many people telling me that I'm gonna come back to Mage, eventually…

There was a long gap between each of the Mage volumes. Why such long delays, and why did you decide to come back when you did?

In between Mage, I try not to think about Mage, because I want to keep it super-fresh, and I don't want to get bogged down in ideas I come up with that I might not be able to get to quickly. I don't do any pre-writing, or notes, or layouts with Mage; no thumbnails. I sit down with blank pages, and I just start drawing, and I let it take me where it's going to go. I try to treat it like a Zen approach. And that's not to say I don't think about it at all. I do, but I try and keep it new and fresh every single time.

The first delay was due to Comico’s bankruptcy [in 1990]. And I'm glad it took that long, because I think if I would've jumped into the second Mage right away, it would've ended up kind of ordinary. It would've been Kevin [Matchstick, the protagonist] romping around hunting down monsters, you know? But with the third one, I knew I was going to have my family in it. I was going to have my wife and kids, and I realized at some point, oh, I have to wait 'till the kids grow up. If I try and do it when they're young, I'm going to idealize them too much; I’m not going to show a complete version of them. I have to realize what sort of people they're going to eventually be before I can portray the people they were. And as I said, that's just always been the case with Mage. More of my life needs to roll by so I can reflect upon it and mythologize it.

And the character really is your most autobiographical, wouldn’t you say?

Yep. And I will say, even that was unintentional. The way that came about was years beforehand, I had this big interest in Arthurian legend. And of course, part of the Arthurian legend is that King Arthur will come back someday. So I had started another version of what became Mage long before I was even close to being able to handle something like that. I produced only two pages, and it was much, much, much more traditional, and ordinary, and boring. And then DC announced they were going to do Camelot 3000, and I was like, “There goes that idea.” Because that story's been done, and that Brian Bolland guy draws a little bit better than I do. [Laughs] So then it came out, and it just seemed so ordinary to me. It seemed like nothing's really changed. These are guys running around the contemporary day in the same armor they wore back then, and King Arthur was even in a Superman costume: he was wearing red, yellow and blue. And Merlin looked exactly like the Merlin you would picture. And it's like, this just is not intriguing me at all. So maybe there is another way for me to do this, you know?

So one day-- this is when I was living in Philadelphia, and I was down on the docks one day, and I was just sketching at that point. And I did a sketch of myself kind of leaning back, sitting. And I had done self-portraits before, but they were all always a little more idealized, trying to make me seem a little more interesting than I was. And this was the first one that looked kind of mundane and world-weary. And it really struck a chord in me that this was the approach I needed to take if I was going to retell King Arthur. You know, when you look at King Arthur, it takes place in the technology of its time. I had to make it take place in the technology of my time. I didn't know anybody that ran around in armor and swords; I knew guys in jeans and t-shirts, and wandered around through the alleys, you know?

And I knew it was okay to base a character upon yourself visually. I mean, Charles Schulz was Charlie Brown, right? I know you know what Dave Stevens looked like: he was Cliff Secord. He was the Rocketeer. I even maintain that Jeff Smith looks like [Fone] Bone, for God’s sake. [Laughs] What I didn't realize was, as I was telling the story, how much of my life I would incorporate into it beyond just the look of guys in t-shirts and jeans. There's the old funny line of, “Listen, kid, I paint what I see,” and that's what I ended up doing. I just found that I was inadvertently pulling in these aspects of my life, and mythologizing them, and making an allegory out of them. It was only afterwards that I realized how I should be more deliberate about that. I had just kind of stumbled my way through that first one.

Additionally, I didn't know anything about Joseph Campbell and the hero's journey at that point. And when I read The Hero with a Thousand Faces, you read the steps in the first stage of the hero’s journey, and it was like reading the plot points for Mage. And I was like, “Well, I got that right.” But it [mostly] struck me how hardwired these archetypes are in the human psyche, as [Campbell] maintains. So there again, with the second and third one, I researched much more of what Campbell pointed out as being the aspects of the hero's journey, and more deliberately tried to incorporate them.

Which gives it, if not quite as much finality as Hunter Rose dying, certainly a sense of resolution, since you’ve taken that hero’s journey to its conclusion.

Yeah, at this point, I can't conceive how I would take it further.

Unless maybe to make it generational, the way you have with Grendel.

That is an option. In fact, if you look at the very last page of the last part of the trilogy, his son Hugo, who's an analog of my son, is wearing a Mage hoodie. And whereas the rest of the family's kind of focused on the house, he's looking off to the side, off-panel.

So would you object if Brennan wanted to take it on and continue the story?

Probably not, no. We’ll see whether that happens or not, but yeah, I would bequeath it unto him. [Laughs]

A final question here: what's your sense of comics today? Do you feel like there's a good future left in the business?

You know, on one level, you have this utterly rich array of material and creators. On another level, I look at some of these books that are highly lauded, and it looks like the guy drew it in an afternoon. I have to think that craft and a certain level of artistic mastery really needs to be in place. And I also just kind of feel like there's too many bands, you know what I mean? [Laughs] It’s like, Jesus, everybody is a comic artist these days. So I don't know. I mean, eventually I think that the wheat will be separated from the chaff. People are not going to be satisfied with stuff that looks like it was drawn in a week. But, again, there's no denying it's great that there's so many female creators now, and creators of all political stripes, sexual stripes, racial backgrounds. It's great. You know, it used to be a boys’ club.

Before the advent of modern cinema, we used to try and discuss what was it about comics that made it different than film. And it used to be that in comics, you could draw anything; anything can happen. Well, now that's achieved in cinema, you know? And now I think there's a level of intimacy that is unique to comics. When you're watching a film, you are not really participating. It's happening to you. When you are reading a prose novel, you're doing a lot of the work; you're filling in based on the author's description. With a comic, you are actively involved in the aspect of reading, which is intimate. And yet you also have the joy of these fabulous visuals to accompany it. There's an intimacy. I'm sure you know how many people discover comics later in life and get the bug hard - it’s almost like a heroin addiction. I think it's that level of intimacy that is so appealing to people.