There are any number of overused terms and phrases in the critical lexicon these days - it almost goes without saying, for instance, that “curation” will be inserted into any review of an anthology in place of “editing”, and that your standard narrative comic will be discussed in terms of the character's “arc”, their “agency” (or lack thereof), and the manner in which their “journey” purportedly “speaks to the concerns of” somebody, somewhere, in some fashion or other. Sometimes this claptrap is actually true, but that doesn’t make reading these trendy catchphrases for the umpteenth time any less tedious.

You’ll have to forgive me, then, for stating here that the comics of Yorkshire-based cartoonist J. Webster Sharp have a very definite “dreamlike” quality: a tired description for work that’s either partially or completely unmoored from the strictures imposed from without by the ever-weakening vestiges of what was once thought of as consensus reality. In my nominal defense, the term absolutely applies. Furthermore, to say that Sharp’s body of work belies an “auteur sensibility” is equally unoriginal, yet also true: there’s no one else making comics the way she is, and there’s no mistaking one of her comics for somebody else’s. Her concerns, fixations and flights of fancy are more or less entirely her own, and her means of communicating them are likewise utterly unique. Her training as a fine artist (specifically a portrait painter) obviously influences her modes and methodologies of expression, sure, but beyond that? One might almost be forgiven for thinking that her perspective is that of a true outsider artist.

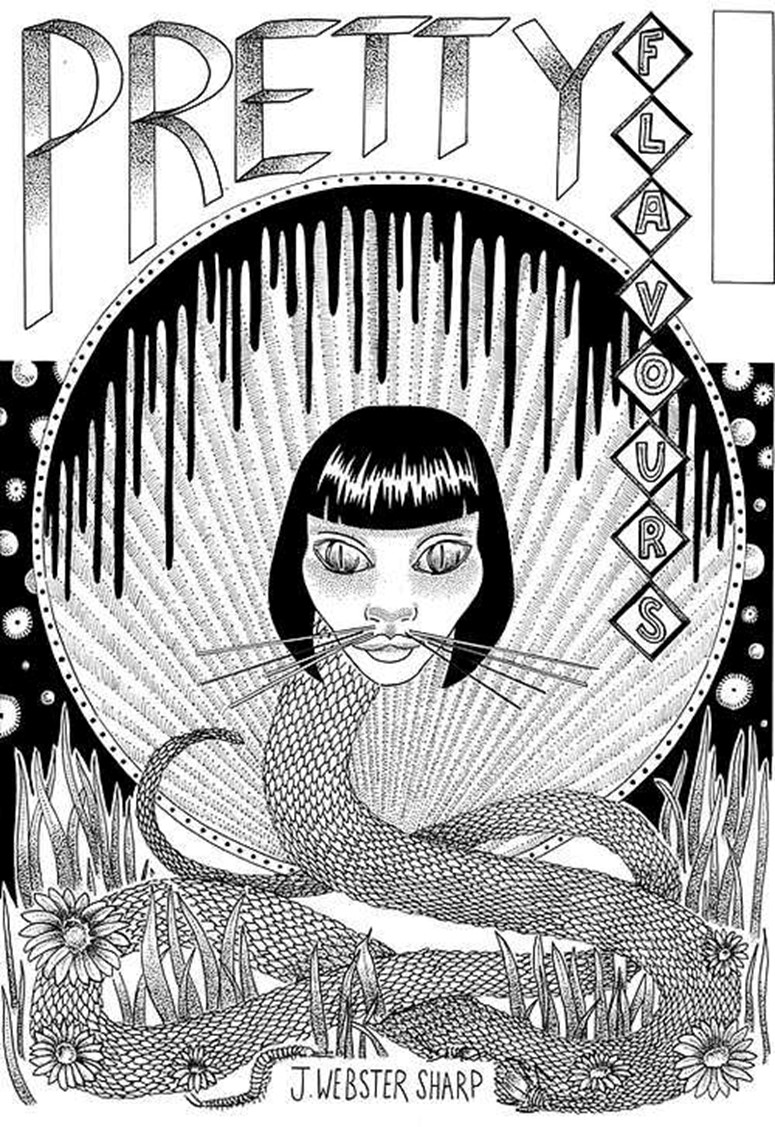

While we’re serving up the clichés, I should also point out that Sharp arrived to comics “fully-formed”, with a clear idea of both what she wanted to do and how she wanted to do it that’s since proven unwavering. Whether we’re talking about her ongoing solo anthology series Fondant, or her one-off comics Pretty Flavours, Sea Widow and Jade and her Schizophrenia—the lattermost written, for the record, by her sister—all of Webster's books have a cohesive through-line binding them together: thematically, conceptually, aesthetically, and, perhaps most important, purposefully, in a way that’s impossible to miss. Sharp is building outward and upward simultaneously, constructing an edifice composed of discrete parts that don’t necessarily fit together, but morph and coalesce into (here we go again, sorry) “a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts”. The fact that she’s only been at this for about a year and half is truly staggering to consider, and leads the reasonable observer to conclude that this is an artist who’s been storing experiences, ideas, feelings, and influences for a long time - all that was missing was finding the ideal means and medium through which to communicate them.

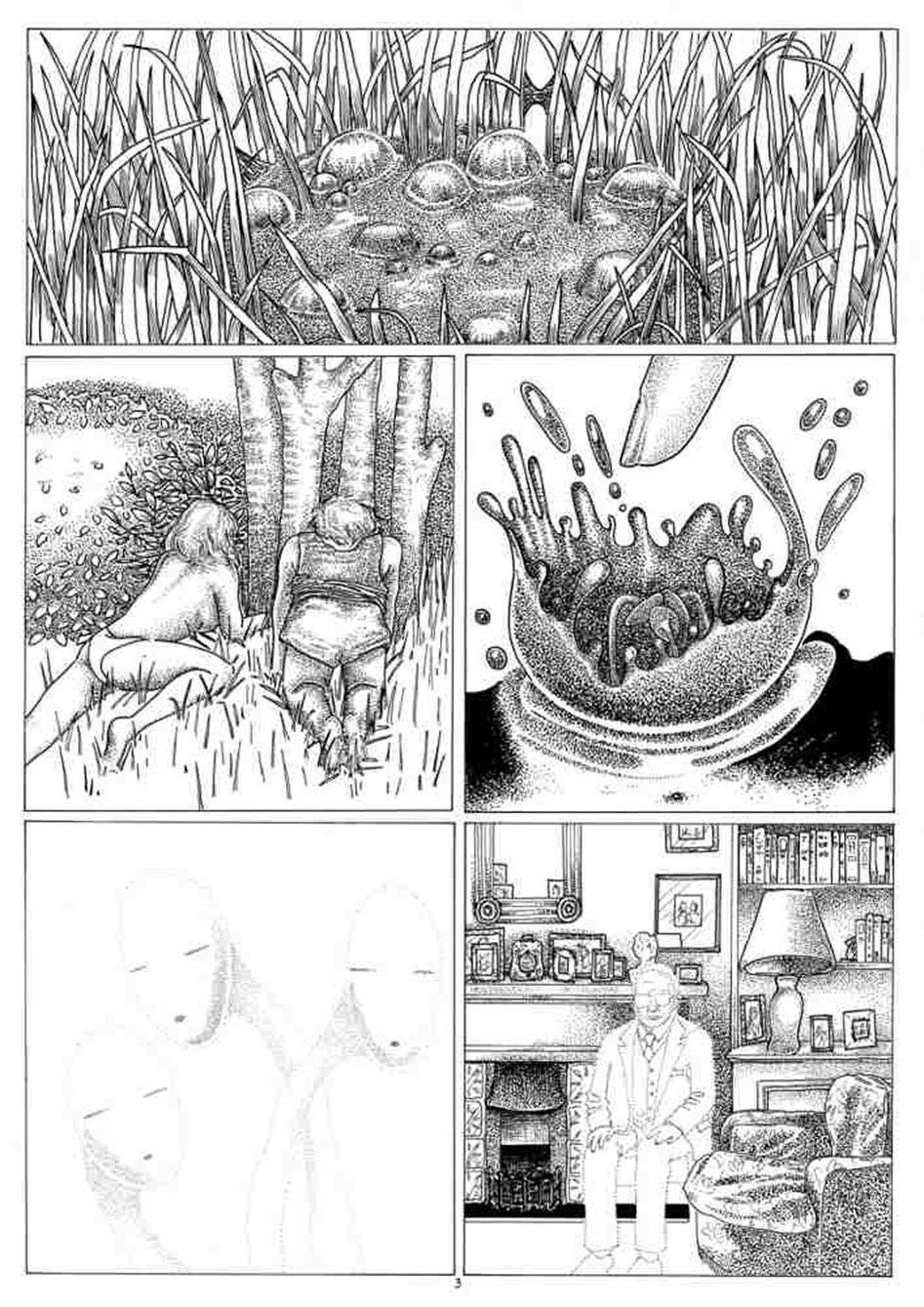

Since settling on comics, the floodgates to Sharp’s conscious and subconscious universes have been blown wide open, and we are all experiencing a deluge as monumental as it is consequential, as unfathomable as it is uncomfortably familiar, as clinical and austere as it is intimate. You feel your way through her comics and intuit or decipher their multiple meanings more than you actually “read” them, and for those of us who are predisposed toward privileging the immersive, the all-encompassing, even the all-consuming - it’s no reach to say we’ve been waiting for an artist like Sharp every bit as long as she was waiting to discover a creative outlet where she could feel at home.

Most of what I’ve said so far is in reference to the totality of Sharp’s vision, but a piecemeal analysis of each of her comics reveals them to be arms of a starfish: cut any one off and it reveals itself to be self-sustaining organism in its own right, and a sturdy and eminently adaptable one at that.

As an example, the story “Human Furnishings” in Fondant #1 offers a unique perspective on the subjects of voluntary depersonalization, physical torment, and biological decay, featuring as it does a number of women who (at least if the sparse captions are to be believed) choose to serve as, well, objects of furniture for reasons we’re only partially privy to, only to find said servitude comes with unexpected dangers in the form of woodworm infection. Before things become even more grotesque than they already are, though, a couple of the young ladies who are either less than enamored with their new “occupation”, or who may have found themselves trapped in this house of horrors against their will (it’s not entirely clear and can be read either way), put paid to the situation by starting a gasoline fire that consumes everyone and everything in sight apart from them. Disquieting stuff when taken on its own, to be sure, but as the themes explored in it are ones to which Sharp returns at other times, in other ways, and from other perspectives, it can also be read a one “chapter” in an unfolding exploration of uncomfortable (or downright taboo) subject matter.

Taking things a step further, there’s really no single issue—or, indeed, single story—within the Sharp oeuvre that doesn’t hold up to multiple readings, interpretations and analyses. Hell, most of her stuff demands multiple considerations and ruminations and, given that fact, it’s incumbent upon me to let prospective readers know that they should expect to spend a lot more time thinking about these comics afterwards, and that complex and even contradictory reactions to them develop over the course of this “post-consumption” period. What they mean to you two weeks or two months down the road will differ substantially from what they seem to be saying at first. Which one of these many views is the “correct” one—or if such thing as a “correct” view even exists at all—is a matter for each person to decide for themselves, but to briefly return to our earlier theme of hackneyed clichés that are nevertheless disturbingly accurate, these comics are “all about the journey” in a way that few others which purport to be actually are, and the journey they take you on is qualitatively different to almost all others: it’s not one where the artist dictates the terms or even takes the less myopic route of suggesting the lay of the land, it’s one where the entirety of what they are communicating is up for grabs and there are no “right” or “wrong” ways of first taking it on board and then unpacking its contents and their various and sundry implications. Sharp is a cartographer, then, of sorts, but one who displays an inherent trust in her audiences’ ability to act as their own guides.

Not that there aren’t signposts along the way, mind you - particularly in the form of recurring imagery, motifs, and figures. Whether it’s lizard people, bondage devices and fetish costumes, feet, or mutated genitalia, Sharp’s comics are awash in self-referential visual cues that lend credence to the idea that what we may be participating in is one long connected work presented not so much in linear “order” as a continuous feedback loop. Indeed, people, places, animals, and things often have what would appear to be almost entirely acausal relationships with one another that exist either outside or apart from time itself as it’s generally perceived. Even “side” projects Jade and her Schizophrenia, a recounting of her sister’s struggles with mental illness, and Sea Widow, an surreally emotive rumination on loss heavily informed by the death of Sharp’s husband, don’t fall entirely outside the shifting and amorphous de facto “boundaries” of the artist’s pointillist id channelings. There is an automatically-drawn quality to all of this fearful beauty (or beautiful fear?) that betrays very little to nothing by way of mediation or self-censorship, which is why it came as no surprise to this author in a recent email exchange with Sharp when she stated that “I would be producing this work whether anybody bought it or saw it or not. Just like when I was painting. It’s important I do this for myself.”

What was surprising to learn, though, is that Sharp is in no way particularly influenced by her dreams, as she confesses that “my dreams are not as abstract or absurd as I would like, I dream mostly realistically and about people I know, they are bland and true to life. The only times I have bad dreams are during periods of massive upset and stress. I used to dream about cutting off the top my head, a skull cap, scooping out some brains and stapling it back on, and going about a regular day hoping no one would notice. I dreamt that over and over. But I wouldn’t draw this.” Color me downright taken aback by that statement, to say the least.

If her dreams don’t inform her work in any appreciable way, then what does? “I am influenced by images, lives, events, anything unusual that pushes me to explore the way I create graphic works,” states the artist, “panels of other comic artists, close up intrusive shots in film, photography and pornography. Reading poetry. These push me to construct associations between real and imagined visuals and make connections which shouldn’t exist, I turn these into silent stories. I am charging my pages with something. Maybe that’s what attracts people to them. I am a heavy collector of images and stories, reference material. I have boxes of clippings from over the years, all kinds, if I see a personal ad which is amazing I keep it. Anything to do with the body and psychology, medical book pages, old pornography, parapsychology…. I get ideas too fast! But that’s how I know they’re right, if they come slow... they’re wrong. I like material which makes my mind race.”

Slightly more in line with my own ideas about, and perceptions of, Sharp’s body of work as a whole are her words in regard to what she is hoping to communicate with it: “How people construct an identity from the detritus of experience I will always love exploring, the biology of an emotion or memory, the loss of innocence. If only I could explore these like the insides of a small creature. The facts of my life have damaged me, it’s where all of this comes from. Experiments in silence, removal of speech, I want to see how far I can push the silence. When you live in fear of your own voice, making graphic art is perfect.”

As far as why the comics medium is the perfect one for the type of “stories” (for lack of a better term, even though it often applies only tangentially) she wants to tell, Sharp minces no words when elaborating on her commitment to her chosen means of communication, saying “from the ones I saw when I was little, these cheap, gory EC Comic type ones that smelled funny and square printed black and white war stories, to the 2000 ADs and Clowes I devoured later on, here was a visual media that had more freedom to explore narrative using images than any other type of creative expression I had experienced. Comics could let me communicate my ideas in a way that painting couldn’t. The atmosphere I wanted to build on a large scale was completely accessible to me on the page. The multiples, the repetitiveness. Comics grew out of the paintings, I will never paint again. Comics are these perfect pieces of existence, they can be anything, perfect if what you want to communicate is very dark. You can make this ill world in this intimate space.”

For my own part, I’m less inclined to label Sharp’s world as an “ill” one and more biased toward describing it as a “startling” and perhaps even “amoral” one. Clearly, a good number of her characters are subjected to proddings, probings, and even violations that appear in no way to be consensual, let alone voluntary, but the context in which these events are taking place is so borderline-unknowable that accepted standards of “right” and “wrong”, “good” and “evil”, seem not just pedestrian but entirely inapplicable. Unease, discomfort and disgust are certainly frequent and in no way unjustifiable responses to much of what she exposes readers to, but even her most debased and frankly perverted scenarios are no mere exercise in shock value for its own sake. In much the same way that “extreme” transgressive authors such as Dennis Cooper, Peter Sotos, Isabelle Nicou and Audrey Szasz have plumbed the depths of the victim/abuser relationship in order to flesh out a more complete understanding of the urge to both do harm—or even, on occasion, to receive it—Sharp uses her art to explore profound yet disturbing questions about the sadistic impulse and how intrinsic it may or may not be to human existence - and ditto for its masochistic polar/complementary opposite.

In the third (and, to date, most recent) issue of Fondant, for instance, the opening story—titled “Ballet”—depicts a prone and helpless young woman leashed, caged, and displayed in front of an audience, her hands surgically replaced with two more feet and her four shoes stuffed with insects. Her captor appears to be a guy dressed in 1960s-style LaVeyan Satantic garb, but he could just as easily “simply” be the master of ceremonies, or even yet another observer. Their relationship is unclear, as is the relationship of two young children, conjoined by a snake-like lower half of their bodies, to the rest of the proceedings. In short order, the kids are separated in fairly crude fashion and preserved in formaldehyde, while their reptilian innards are served to the audience as a meal or snack while they watch a snake/human hybrid ballerina—who may or may not be a transformed and transmogrified version of the girl shown at the story’s outset—dance, decay, and die for their “entertainment.” How much of this is voluntary and how much is anything but is never directly addressed, and the lack of emotional affect in the expressions of the handless girl, the kids, and the ballerina doesn’t clue readers in either way. One is forced to consider all possibilities, then, when it comes to the key question of consent, and none of the potential answers—nor the nature of the characters’ relationships necessarily extrapolated from them—are anything other than disturbing in the extreme. All we know for certain is that some people are being tormented in brutally grotesque ways for the enjoyment of others, and beyond that we’re forced the fill in the very intentional “blanks” ourselves.

Obviously, then, material this combustible would be well outside the bounds of what most publishers would consider touching with a ten-foot pole, but here again Sharp’s absolute commitment to her clarity of vision proves unwavering. “I chose to self publish as it was instant,” she says. “I couldn’t wait. I had no reason to wait, I wanted my work out there as soon as possible, I had gone so long with without drawing, sewing, sculpting, anything. I had to make up for lost time. And I know my work, it isn’t for everybody. It’s silent, the narrative of linked together imagery is disjointed…. And I was producing all of this work and I didn’t want to stop, I was scared to in case all of this went away. And things have a habit of drifting away from me. The ‘do it yourself’ element of anything is so attractive to me, possibly from growing up working class, make do and mend and all that. Having no money growing up really pushes you to create and dream within this fixed boundary. Going to the post office with a bag of orders to mail, my comics going to Rio, Italy, New Zealand… there isn’t really a boundary anymore. I would never have dreamed that comics could do this for me.”

Fortunately, she’s also managed to find an appreciative (if, I’m guessing, comparatively small) audience: “I have been stunned. I can’t believe what I do has spoken to something in so many people. I don’t know if it’s the combination of the stippling and weirdness of the subject matter that speaks to people or if it’s just one of these things… I think of an audience in terms of wanting them to see progress and wanting to keep output consistent, but not trying to ‘out gore’ myself all the while to keep a reader interested.” The end result? Work that is certainly excessive and decadent in the truest sense, but at the same time not particularly gratuitous. The extremes Sharp so skillfully—even painfully—delineates are being shown for a reason, even if those reasons are open to myriad and sometimes contradictory readings, entirely theoretical in nature, tantalizingly out of reach, or any combination of these.

Interestingly, though, in the midst of all this lavishly-illustrated deprivation, degradation, and frequently quite literal dehumanization, this author at least does find hidden within Sharp’s comics something that at least resembles hope as it’s generally understood - it’s not, however, the garden-variety “hope for a better tomorrow” that we’re all accustomed to (past, present, and future being utterly meaningless concepts in the context of this work anyway). Rather, it’s the hope of achieving a more complete and holistic knowledge of ourselves by confronting—ultimately perhaps even embracing—those parts of our psyche that we keep locked away in a strong box out of necessity for our mental and emotional survival. Hell, maybe even for our own physical safety as well as that of others. Sharp picks up where almost all other artists leave off in their attempts to define not just the human condition, but human nature itself - and while she may offer no hard and fast conclusions, or even posit much by way of guesses and conjecture, she asks all the right questions; and, more importantly, she demands readers attempt to answer them for themselves.

Sharp takes us into and through, in the words of her fellow British comics creator Alan Moore, “the most extreme and utter region of the human mind, a dim sub-conscious underworld. A radiant abyss where men meet themselves...” Admittedly, Moore’s iteration of Sir William Withey Gull went on to define this as being no less than Hell itself, while Sharp, for her part, would seem to posit nothing so dramatic, but you have to wonder: if the implication running through her work is that this is simply us, as we really are, once all pretense is stripped away, is that more terrifying than if we were in Hell, more oddly reassuring - or both?