I met the Valencian illustrator and comics artist Ana Penyas in 2018 and 2020, and each time we talked, I was amazed by her work ethic, her brilliance, and her humility. In 2018, Penyas won Spain’s most prestigious comics award, the National Comic Award, for her debut graphic novel, Estamos todas bien [We’re All Just Fine], which has just been published in English by Fantagraphics. It was her first full-length comics work, but a look at her previous projects reveals a consistent output of superb and genuine art.

In her work, Penyas takes a radical approach (in the words of Angela Davis, she “grasps things at the root”), staying grounded in the problems and joys of the common people. Her fanzines and illustrated stories like Mi barrio [My Neighborhood], La Punta [The Edge], and Cabanyal Any Zero [Cabanyal Year Zero] illustrate the testimonies and dynamics among neighbors in small towns of Valencia fighting against gentrification; Etnografia d’una exhumació [Ethnography of an Exhumation] and Los días rojos de la memoria [The Red Days of Memory] tell the stories of real people who continue to fight for justice almost 40 years after the Francoist dictatorship; Senda de cuidados [Path of Care Work] and Territorios domésticos [Domestic Territories] depict care workers’ struggle for their rights. These projects provide an overview of some of the artistic concerns that preceded We’re All Just Fine and remain a consistent focus in her career. In 2021, she published Todo bajo el sol [Everything under the Sun], in which she uses the story of a fictional family in a small town of Valencia to explore the global neoliberalism that has shaped displacement, mass tourism, and urban speculation. It has already been translated into German and won the Éco-Fauve award at the Angoulême International Comics Festival in 2023. In 2022, Penyas collaborated with the anthropologist Alba Herrero Garcés and several women who work in domestic and care work on an exhibition at the prestigious Institut Valencià d’Art Modern (IVAM) that explored the genealogies of domestic and care work. Ana Penyas is one of the most visionary, socially-conscious, and sophisticated artists of Spain—and in the world—today. It was wonderful to meet her for this interview.

-Esther Claudio-Moreno

* * *

ESTHER CLAUDIO-MORENO: You were the first woman to win the Spanish National Comic Award in 2018 for We’re All Just Fine. This comic is the result of an evolving style and coherent career related to activism that centers around themes like collective memory, political violence, gentrification, and the role of women in society. How has activism shaped your work? Did anything change when you won the Award?

ANA PENYAS: The National Award gave me a precious time. To start with, I never thought We’re All Just Fine would be so successful, not in my wildest dreams. Goes without saying that I never created it with the intention to win anything. I was aware that people liked it, but that’s all. The origin for We’re All Just Fine is a short story that had a very good reception among peers and faculty in my Fine Arts class, but I didn’t expand it thinking that I would gain even more popularity or anything like that. I’m as surprised as anyone else.

Before the Award, I worked full time as a graphic designer for different companies and publicity, and I worked on personal projects in my free time. It was exhausting. The Award has given me the opportunity to say “no” to commissions and focus on my career. I’m not rich and I still need to accept some jobs, but I can be more selective.

About activism, it has been immensely relevant, because it gave me a space to experiment and grow without the pressure of a job or a grade. I could also find my voice. I have long been part of different activist groups, but I didn’t always have the feminist perspective I have today. I had to learn little by little. But I’m not an exception, this has been a social thing, a collective change that has developed little by little. When the 15-M Movement1 broke out—which is when I went back to Valencia to start Fine Arts—feminism was brought to the forefront. In the 15-M we saw how feminism was not just one aspect or goal, it was foundational to the demands of the movement, because it provided an inclusive framework that made sure that no one was left behind. Achieving something big by relegating most voices was not an option anymore and that is, in part, the feminist discourse, but it had not always been so strong or visible. I have always been involved in activism, and not even in leftist movements would you see the presence of feminism that we have today. I myself had to grow and learn to be able to express an honest and committed perspective from my positionality.

You mentioned the origin of We’re All Just Fine. Can you describe it in more detail? What motivated you to tell the story of Maruja, Herminia, and many other women like them?

Well, it all started from a short assignment for university. We had to create a story about one day in our lives, but I asked if I could do it about my grandmother Maruja and the professor agreed. I had recently visited her with my father. It was the first time she was living alone, and I found her quite sad and a little frail. It stirred something in me, and I was inspired to tell a day in her life rather than mine. So, I created this story where Maruja tries to stand up from her armchair but it takes her so long that in the end she asks the neighbor for help. In the class, people liked it a lot, so I realized it had the potential to become a longer project, and now it constitutes the beginning of We’re All Just Fine.

Some time later, I found this festival for self-published works and I submitted Maruja’s story with another one about Herminia. The one about Herminia is also in We’re All Just Fine, but it is based on a story written by my mother when she was young. It was called “Tal vez mañana” [“Maybe Tomorrow”], and it depicted how Herminia had to leave many tasks for the next day even though she had worked ceaselessly at the household chores all day. A publisher saw my fanzine and encouraged me to transform it into a longer comics story. I worked hard, but when I had 50 pages he dropped out. So I went on and finished it on my own, and I won my first prize.2

Apart from that, the origin is obviously affection. It was… mmm… not quite sad, but it did affect me to see my grandmothers getting older every day, sometimes getting more dependent or a little lonelier. It is the most personal project I have done.

And as a woman, I have a debt with the generations of women who were “somebody’s” wife, daughter, girlfriend, sister… this is why I needed to tell Maruja’s and Herminia’s story - to bring them to the foreground.

I would say that feminism frames the work and gives meaning to ostensibly insignificant, routine acts…

Yes, I mean, I have a political and feminist perspective and it’s there. That’s more like how I treat my characters. Then we have the main topics, like collective memory, or the crisis of care.

What I mean is that you didn’t choose a feminist heroine to talk about structural gender inequality. You chose the apparently “boring” everyday lives of two old ladies, which I find brilliant while also a challenging creative endeavor.

I intentionally try to avoid clichés, and I prefer to explore the contradictions, the nuances. But above all, I chose my grandmothers because they express the experience of the vast majority of women. On the one hand, there is this silence about the years of the dictatorship, which is how most people were raised then, especially my grandmothers and other women. They were not expected to participate in public life, least of all of the political sphere. On the other, the majority of women did not take an active role against the dictatorship, but as I hope to show in the comic, that does not mean that they accepted it, nor were they victims. They were common people that navigated the system the best they could. My grandmothers lived the role that women had to play at that time, a role that was similar in Spain and abroad, in the US or anywhere else.

Besides, feminism and collective memory are related; they are both concerned about what has traditionally been ignored, misrepresented, and devalued from History with a capital H. The silences, the facial expressions, the everyday household tasks, the care work… the margins, really. We’re All Fine tells a story of women in the foreground and collective memory in the background.

Can you speak more about your interest in collective memory in Spain?

I’ve always loved history. That was my favorite course at school, and I grew up in a house where it played a big part. But I think it is especially relevant for our generation, given that history was kind of stolen or hidden from us as a society.

In fact, my passion for history and memory led me to embark on my first narrative project, where I learned a lot and which was foundational for the evolution in my style, because it kind of educated my gaze. I learned to tell a story through the small details.

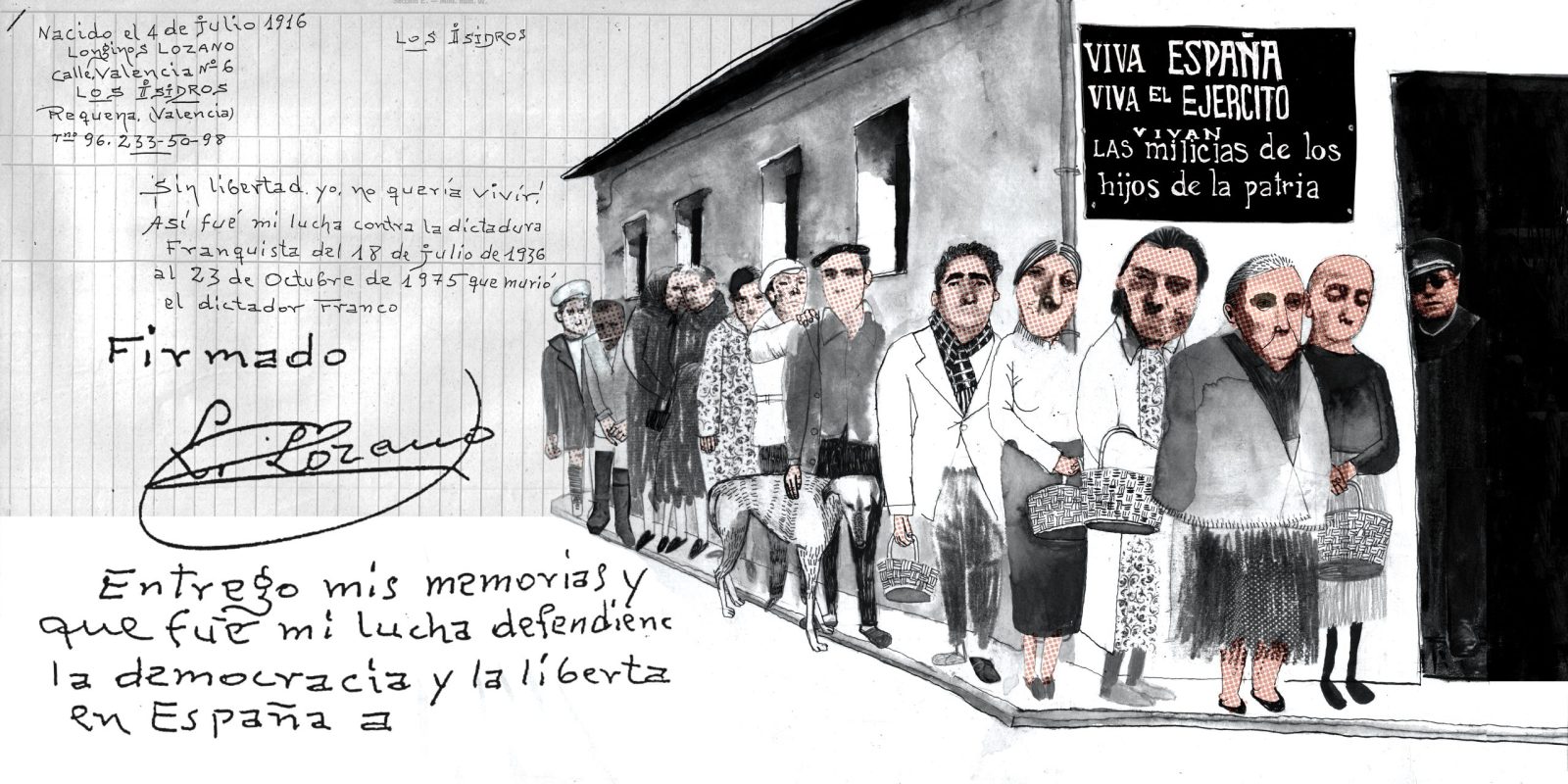

Los días rojos de la memoria [The Red Days of Memory]?

Yes, yes, that one. It all started because my friend Alvaro, who works at two libraries in a small town of Valencia, found the memoir of Longinos Lozano, a very powerful text by an old man who had spent his life fighting for democracy and against the dictatorship in Spain. Alvaro introduced me to his other two friends, two women who were sociologists, and it was very beautiful because we would spend the weekends together in that town - we would work together, interview people, and I learned to use the archive, to interview, to incorporate testimonies… narration is not predominant in Fine Arts. You learn to condense as much information as you can in a single image, so this was an inverted operation. In the end, I created a fanzine in which I illustrated Lozano’s memories, and I submitted it as my final project for Fine Arts. Working on this project, I learned to collect information from objects, places, and above all interviews. This was a very important experience for me, and it’s close to my heart.

In fact, I feel that I’m more like an anthropologist or a social scientist than an artist. And collective memory is a big part of our generation, because memory has kind of skipped generations, you know? I grew up in a house that was open about politics and my father was passionate about history, so when I would talk to others I’d notice how most people didn’t know about our past, that there were gaps.

I find your family more open about it than mine. I was raised on the “hush… don’t let anybody know what you think” (about politics) or the “promise you won’t tell anybody about the family’s past” sort of mentality. It was kind of difficult for me, but from what I saw in We’re All Just Fine, your parents were quite active politically.

Absolutely. I mean, they had to be careful, but both my parents were active in political movements against the dictatorship, so I have kind of inherited that. My father loved history, my house is full of books about the Spanish Civil War, the resistance, and the Republic. My mother was also very active politically, as you see in the comic, so that was normal to me. It took me a while to realize that my upbringing was the exception, and yours was the rule.

Well, also my parents are older than yours. In a way, they’re closer to your grandmothers because they lived through the postwar, through the misery and the worst of the repression…

Yeah, there’s also that, the generational divide. My grandmothers, Herminia and Maruja, were the ones who kept silent and did not want my parents to get involved in anything political.

You’re very graphic. I feel that you communicate more with the image and the gazes than with the words.

Well, that’s because I’m very insecure about dialogues. I feel bad for my characters, they speak very little, the poor things! [Laughs]

What??? I love how real they are! You perfectly captured the everyday, genuine expressions of our moms and grannies. And you also use the specific terms that are characteristic of different regions of Spain.

Really? Thank you so much! [Laughs] I’m always afraid that what my characters say will not sound natural or plausible. I try to be as true to them as I can.

Your characters express with just their eyes, or with their gaze, where they direct their vision…

One thing I have noticed is that my characters hardly ever smile or laugh [laughs], but I do laugh a lot!

[Laughs] They don’t need to talk. Really. I feel like sometimes, for example when young Maruja is alone in the bar at night and she sees the Civil Guard, it is a little like time stops, and for me, as a reader, this kind of pause or this moment with no words, gives me a break to pay attention to the details, to the visual cues.

But it is also something I enjoy in an aesthetic way, because I have a preference for those little things that say a lot over a more action-driven narrative. In fact, that’s the way I learn. I appreciate the big, grandiose stories or topics, but I learn more through the small moments, the everyday. Obviously, drawing makes you be very observant, and I can’t help but pay attention to the little gestures or aspects that might go unnoticed on a normal day. But apart from paying attention to details, I’m interested in how small stories speak to the greater picture. I admire the kinds of films where time passes slowly, that revel in the details. I definitely don’t like to be obvious. I prefer to suggest, like so many other artists in comics and other media that I admire.

Like who? What are your influences?

I’m very influenced by docufiction, [Joshua] Oppenheimer and the like. I would like my comics to be a form of docufiction in that sense. In fact, I learned to narrate through small details and costumbrismo by working with sociologists, anthropologists, etc. In a sense, sometimes I consider my work closer to anthropology than to Fine Arts.

In regard to visual style, I really like Expressionism: Otto Dix, George Grosz. The visual style of Russian Constructivism, the very sober use of colors…

And I also admire photography. I am more a photographer than a cartoonist. In fact, I consider myself a kind of frustrated photographer.

Tell me more about your technique, the mix between photography and drawing…

Yes, the “transfer.” Well, it is not “my” technique. It’s nothing new, and people use it in design, publicity, art… what I do is that I first draw the storyboard by hand, and then I choose what elements will be photographs. Then I photocopy the photograph with very high resolution and a lot of ink, and I transfer it onto the parts of the page I chose. I use a gel to transfer them to the sheet. And then I draw on top of it, or I contour it, and I do the rest of the drawing.

In fact, your visual style is a kind of collage, and your drawings kind of imitate how children draw.

Absolutely. And collage facilitates contrast. You can mix two impossible, clashing worlds, two different realities. And the naïve drawing style is again the contrast, but in this case the clash of “adult” or “serious” stories that are drawn in a childish way. Also, I’m not so good with perspective, so I just completely tear it apart! [Laughs]

Yes! I love the first page of We’re Just All Fine where you put together the eyes of Maruja and the lady dancing on the TV, because this contrast makes the sexy poses—that is, the sexualization of the female body—look ridiculous through the eyes of an old lady.

Yeah [laughs], it’s the clash, the conflict…

It reminded me of Eisenstein’s concept of montage, like that mix of takes that make the whole bigger than the parts and whose understanding or interpretation is kind of unconscious and different for each reader.

Yeah, I love Eisenstein. Collage allows for that clash between violence and silence, the popular and the elitist…

And feminism directs our gaze to the margins. The history of women is made up of scraps, it constitutes a kind of collage itself, of putting together the few pieces left from the hegemonic discourse. It is about telling what nobody cared about, nobody included, nobody paid attention to - and carefully, and with patience and affection, you sew it all together like a quilt. Your style is kind of craftivist…

Kind of what?

Craftivism?

What is that? [Laughs]

It’s reclaiming the domestic, handcrafted tasks that have been traditionally seen as women’s “useless” and “shallow” activities, and bringing them into the public, political arena. For instance, embroidering political and feminist messages. It’s part of the DIY culture, obviously, these unrushed, deliberate activities in opposition to fast, consumerist dynamics.

I didn’t know about that! But yes, in that sense, We’re All Just Fine is a little bit like a work of craftivism.

Your style is not the classic cartoony drawing. Did you set out to create comics initially?

Not really. At least that was not my priority or my natural form of expression. By the time I started Fine Arts I had already developed a personal style where I used photographs and drawing for jobs in publicity and graphic design, but I did not consider using the image to narrate, or not in the way comics do, with panels and so on. I would also put my skills to work in the service of causes I believed in. For example, if I was in any sort of activist group, I would be in charge of posters, banners, and brochures. The closest I got to comics was illustrating projects like Los días rojos de la memoria and other stories about social concerns. Through these collaborations, I started considering the possibility of using drawings and texts to narrate.

What inspired you to give comics a chance?

Well, to see the work by authors like Jorge González or Gipi made me realize that my style, my mix of photography and drawing, could have a place in comics. It’s obvious that I don’t draw with the characteristic style of comics. I mean, I did not make an effort to develop a cartoony, comic-like style, because that was never my goal. When I saw González and other authors’ work, I understood that a style like mine could also be used to tell a story in the comics form, and it inspired me to explore this option.

What’s your criteria to choose what will be a photograph and what will be a drawing? I thought that We’re All Just Fine used photographs of the fabrics of the clothes to underscore the invisible—and unpaid—labor of stay-at-home mothers.

Well, yes, in a way I did pay a lot of attention to fabrics in We’re All Just Fine. To every aspect of domestic life, for that matter, because that was their world. In this sense, to put a pot or a laundry basket at the center is to make it relevant. I wanted the reader to pay attention to all the elements that constituted the universe of stay-at-home mothers but were ignored—or even belittled—by everybody else. It is about the dignity of the tasks, the tools, and above all the women that made everything work. For centuries. And for free.

'Cause women take care of the leftovers of capitalism, but “We’re All Just Fine,” right?

[Laughs] Perfectly fine…

Going back to the photographs, you include some celebrities or icons, like Belén Esteban3 in the end, when Maruja says, “We’re all just fine.” [Laughs]

[Laughs] Yeah, well, of course I had to use photographs with characters that are so well-known. Besides, that’s the “reality” for so many old people, you know? It’s in the very name, “reality” TV. It’s this pseudo-reality that is more real than real life that acts as a substitute for some form of social life. And in the case of some old people like my grandmother Maruja, who feel so lonely, works as some sort of illusory company.

What’s real, what’s not, drawing vs. photography… I love all that! And of course you included Almodóvar…

Yeah, I mean, he is too iconic. Him and [Fabio] McNamara…

So how do you choose what goes as drawing and what as photograph?

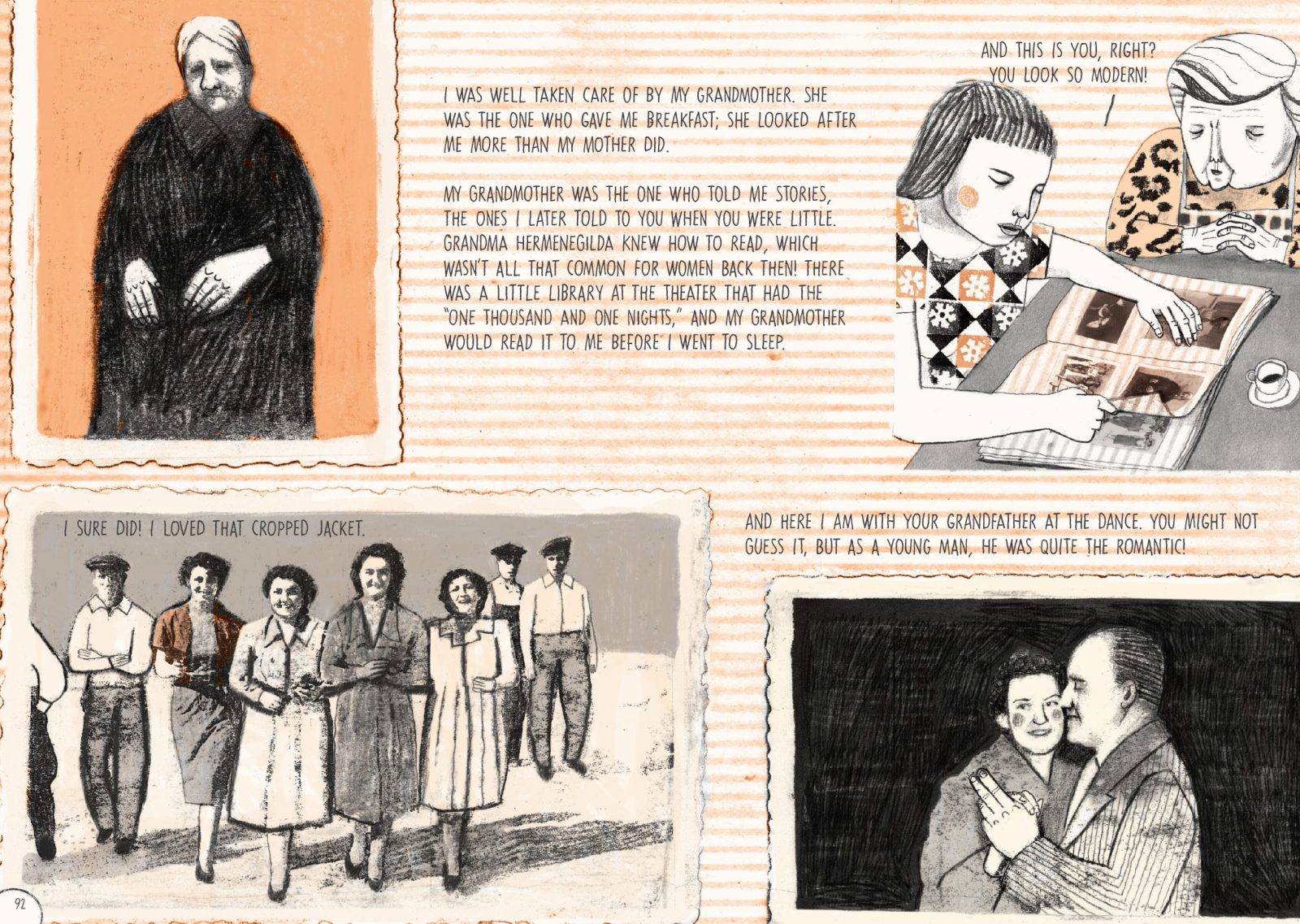

I don’t really think too much. I mean, Maruja, Herminia, and other characters, especially when they talk, they must be drawn because I need to move their face, change their facial expressions, etc. In general, I like using photographs in the objects and scenery, it makes it look kind of real and that is very present in my next project, Todo bajo el sol. Besides, in We’re All Just Fine, they had an emotional meaning for me, like the pictures hanging from my grandmas’ walls, which I’ve seen a thousand times and they’ve been a part of my life, but I’d taken for granted until I started the comic. When I interviewed my grandmothers, I learned their story. For instance, I had seen the picture of the clown shedding a tear all my life, but I didn’t know that my grandma had made it herself! I thought she had bought it somewhere. She told me the story because we talked for the comic so, in a sense, the process of viewing domestic life differently that you mentioned before is a process I experienced myself thanks to working on We’re All Just Fine.

Yeah, I love when you say, “There are plenty of love stories, but not so many grandma stories.”

That conversation on the phone is totally true. Maruja had some really good lines, like the one about spending her life mending the bedsheets. That hit me hard.

And mixing photography with drawing is super-interesting when you and Herminia look at the photo album together.

Well, because We’re All Just Fine is like a family album.

How did you work with your grandmothers? Have they seen themselves in the comic? What did they think?

I interviewed them several times, asked them to show me photos, but I also spoke with other relatives. My parents of course, but my grandaunts are also in the book, and they loved it. I did show it to Herminia, who was quite excited about the project, and she understood what I was doing. Maruja was not as aware, because she rapidly deteriorated due to Parkinson’s.

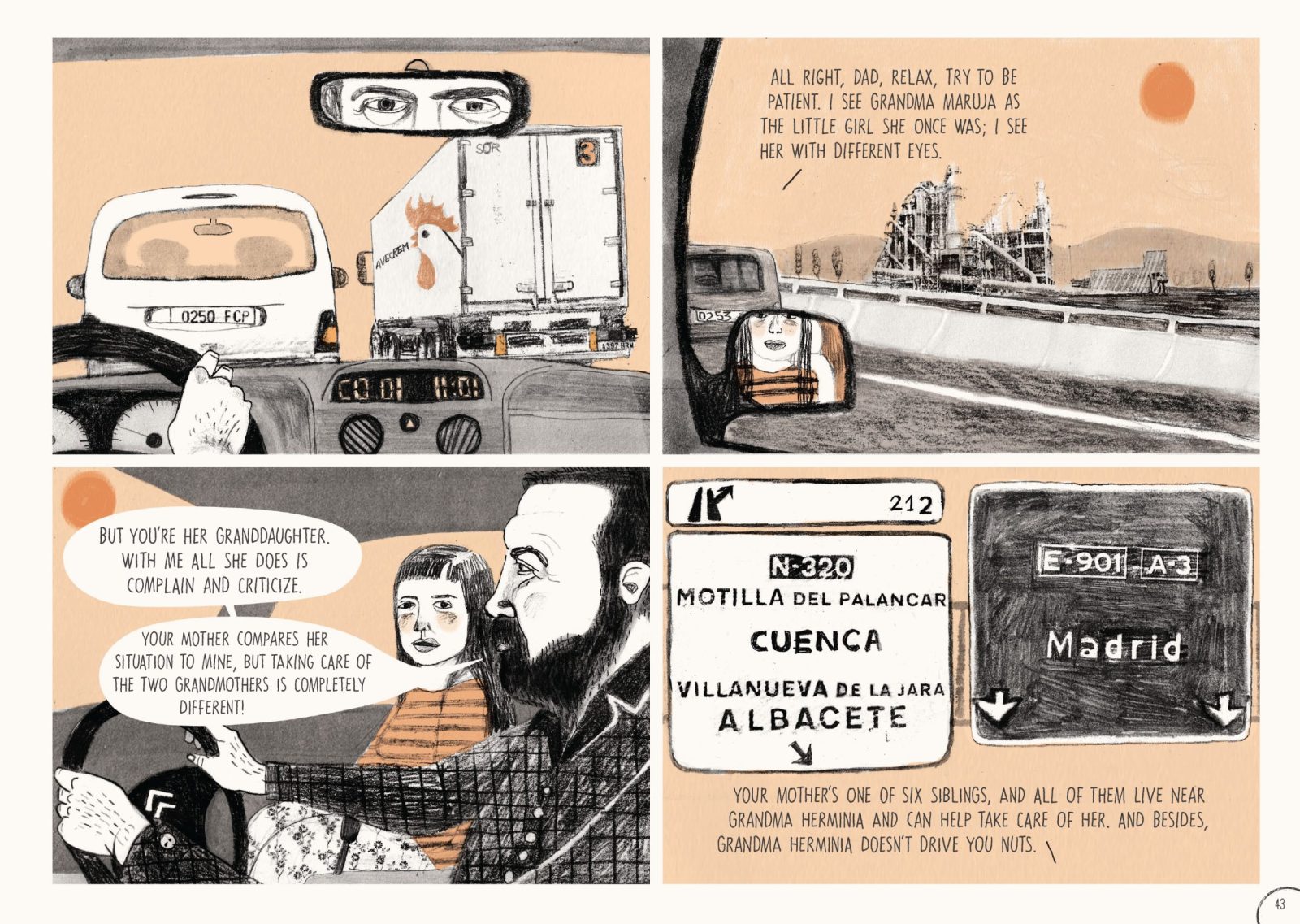

I appreciated seeing that your father had a different opinion than you about his own mother, Maruja. You include this conversation in the comic, and I found it very honest and necessary.

Yes, because I understand that I did have a very sweet relationship with them, but that this was a privileged position because my father acted kind of like a buffer between us. Besides, Maruja and Herminia are human, and they are more complex than just your stereotypical sweet grannies. In fact, one of the most difficult parts for me in this project was to balance their representation. Above all, I needed to make sure I did not victimize them or made them look too fragile and cute. They are people like you and me, and they had their opinions, their character, which was different from mine many times.

Like when Maruja looks scornfully at the non-binary people walking down the street?

Exactly! Her perspective is what it is, you know? It was very important for me to provide a balanced portrayal.

Would you say that color narrates?

Yes, colors are part of the narration and, in this case, they helped separate the stories.

Is there a reason why Maruja’s color is red and Herminia’s is brown?

No, absolutely not. Maybe there’s something unconscious there or whatever… I don’t know why, but when I thought of Maruja, I saw her in red, and when I would recall memories of Herminia, the predominant color was brown or ochre tones. That’s it. In general, because they were my own grandmothers and this is a personal story for me, I used warm colors. One color that’s difficult for me to include is yellow, so I’ve played with it in my next book, Todo bajo el sol. It is true, though, that I like to limit the color palette, to make it a little more minimalistic. It just makes me feel good.

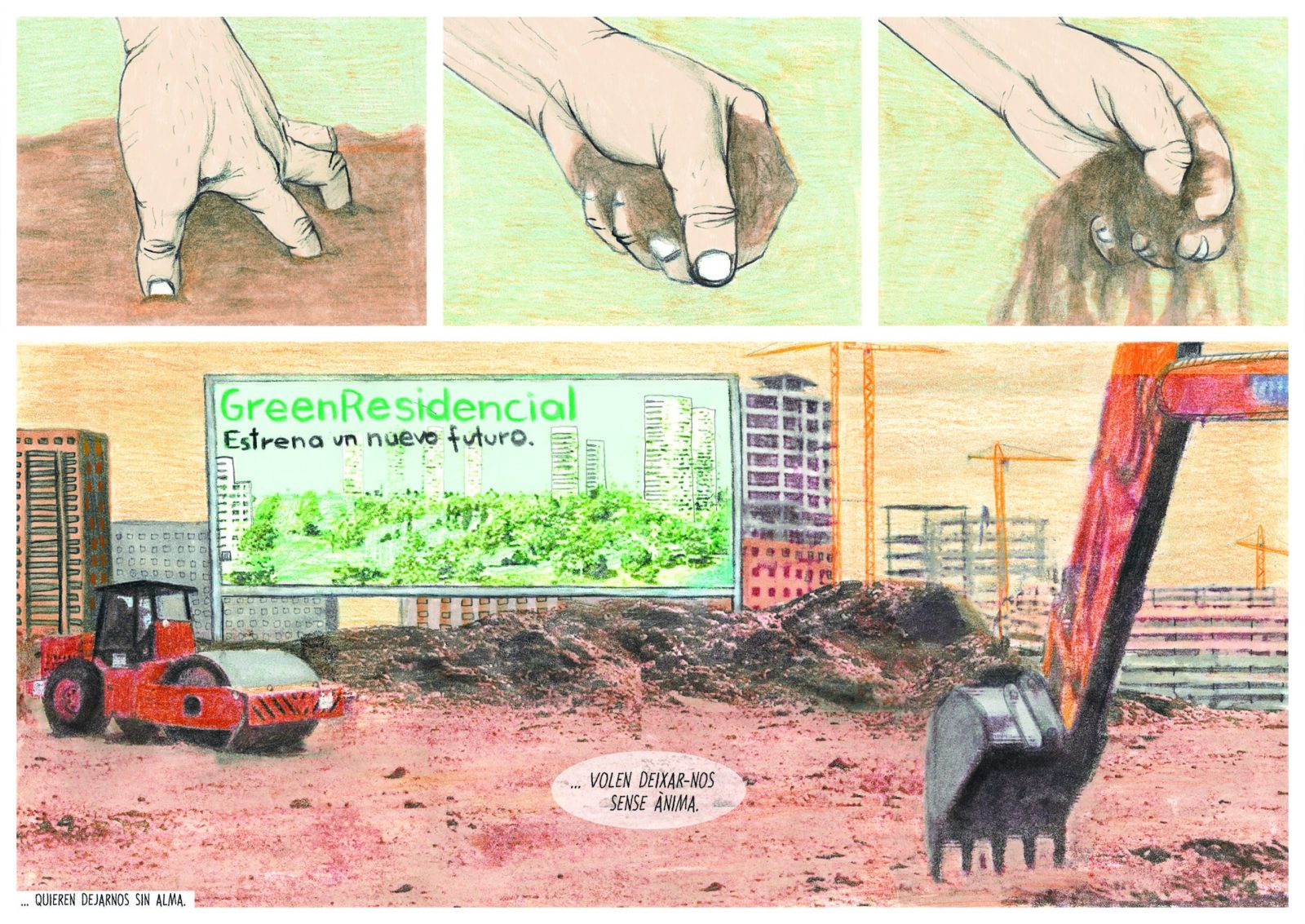

You mentioned Todo bajo el sol, which has become another great success and been recognized with countless awards. It describes globalization, displacement, gentrification, and migration in a small town in Valencia. It covers decades of transformation, describes a wider range of dynamics, and has more characters, so it seems to me a big change from the domestic spaces of your grandmothers’ story.

Absolutely, and it’s 50 pages longer!

And each page counts, right? One sweats over those pages! [Laughs]

Tell me about it! [Laughs] Well, they’re both different projects, because We’re All Just Fine is totally personal, whereas Todo bajo el sol is more like a study of gentrification, the real estate bubble, the economic crisis… so yes, it is bigger in scope but still from the perspective of a fictional family, from the local. I like to anchor my projects in the effects that greater dynamics or structures have on real people, and the other way around, to see the big picture through the eyes of people like you and me. Sometimes, they experience the impact of, say, international dynamics, but my characters are never passive. They navigate the system. And sometimes, they also resist or challenge their circumstances. For Todo bajo el sol, unlike in We’re All Just Fine, the old people in the family are the ones who try to fight more, because they still have the memories of what the place used to be, and it is the young people who try to adapt to rapidly-changing circumstances, to survive the best way that they can.

But in this work, the real protagonist is the territory. We see the transformations over time, the layers of change brought about by different aspects—capitalism, urban development, even publicity and marketing—and the family is more like part of the landscape. I mean, they are important, but the territory is a character itself.

And in We’re All Just Fine, women were at the center, but in this case you focus more on the son of the family.

Above all, I did not want to be pigeonholed. I’m a feminist and my political perspective or personal commitments will always be there, but it is not like I’m going to be telling women’s stories all the time.

Was it very different for you to work with a male character? Because I have talked to some authors who would, for example, only create main characters who are men, and they’ve said they didn’t feel comfortable or even capable of creating women as main characters.

In my personal case, not really, because I have kind of a masculine side myself. [Laughs] I feel very comfortable around men—I have a brother, I have always been very close to my father, some of my closest friends are men—so it’s nothing alien to me. Besides, it’s just a narrative challenge, you know? Like researching and learning about real estate and monetization of land. [Laughs] I didn’t study that in Fine Arts! So it’s just about time, being true to yourself, being genuine and honest, reviewing the characters, all of them, so that they are not caricatures but complex, contradictory, real “people”. So no, it was not hard in the emotional sense, and if there was something challenging, I would just work on it.

What documentation did you use as sources in your work?

Mostly audiovisual, although one of the most useful sources was Alicia Fuentes’ dissertation about visual culture of the tourist boom during Francoist Spain, mainly because it analyzed image: billboards, posters…

Oh, by the way! I forgot to ask about the role of publicity in your work. The billboards in We’re All Just Fine and in many of your previous, smaller projects are so meaningful…

Ah, yes! Well, billboards express a lot in a short time and space, like social transformations that are immensely meaningful. So to me they are like a hallmark that condenses the passing of time. Yes, billboards, banners… they have a role in my work, they are important to me.

But going back to the sources, I used books, articles, but mostly films and documentaries from the '80s and '90s. They’re also useful to me because I play with screenshots. I can include them in the panels of the comic.

And in Todo bajo el sol you included different languages in the comic: Valencian, English, German, Swedish… I find that brave and genuine.

Thanks a lot. In fact, I tried to leave the dialogue in Valencian and not include any Spanish translation,4 but I gave the comic to my housemates and they said they didn’t understand a thing. [Laughs] So I had to translate it into Spanish, because it was more important to me that people could follow the story.

So after Todo bajo el sol, what is your next project?

I don’t see myself making only comics, because it is very precarious, even if you sell a lot. I keep working in other fields. In fact, my next project is with the Institut Valencià d’art Modern (IVAM). I was asked to prepare an exhibition, and I’m working on it with the anthropologist Alba Herrero Garcés. This is a project with interviews, testimonies, and collective work with and about women employed as maids at private households. Alba, the workers, and I are tracking a genealogy of activism for the rights of these employees that goes back to the turn of the 20th century, and it analyzes the fluctuations in time. One of the most surprising things is that we might imagine that things have improved, but when you compare conditions from decades before, things have gotten worse. Now racialization and outsourcing contribute to reproducing power structures, discrimination, and precariousness.

Ana, it was great to talk with you, as usual.

Yes, I had a great time. Thanks a lot.

* * *

- On May 15, 2011—hence the “15-M” name—a massive strike took over the streets of Spain. With more than 20% of the population unemployed, the government instituted budgetary cuts that only increased the polarization of wealth and privileged the banking system over social needs after the 2007-08 economic crisis. In response, protestors took to the streets and occupied city squares all over the country until real measures and steps were taken to fight systemic inequity. Protests continued for an entire month, and the legacy of the movement still reverberates today.

- Estamos todas bien won the 10th FNAC-Salamandra Graphic Novel Award in 2017.

- One of the most famous reality TV celebrities in Spain.

- Spain has four official languages: Galician, Catalan, Basque, and Spanish; Valencian is a dialect of Catalan. Initially leaving the Valencian untranslated was a sort of political choice, to capture the authentic voice of the characters. However, the mutual unintelligibility of Valencian and Spanish proved too challenging to potential readers to not include a translation in the footnotes.