In hindsight, it was so obvious. And I missed it completely.

When I published my book Hemingway in Comics late last year, I was reaching out to my favorite writers to ask for cover blurbs—among them J. M. DeMatteis (Moonshadow, The Amazing Spider-Man). I'd spent years documenting Ernest Hemingway's 120-plus appearances in comics alongside Wolverine, Mickey Mouse, Superman—and exploring the Nobel-winner's cultural impact. DeMatteis responded almost immediately and wrote me the most flattering endorsement.

Almost as an afterthought, DeMatteis told me, “Kraven’s suicide at the end of Kraven’s Last Hunt was partially inspired by Hemingway’s death. I remember being a kid and hearing about how Hemingway died and that image of the ‘Great White Hunter’ shoving a rifle in his mouth haunted me for years.”

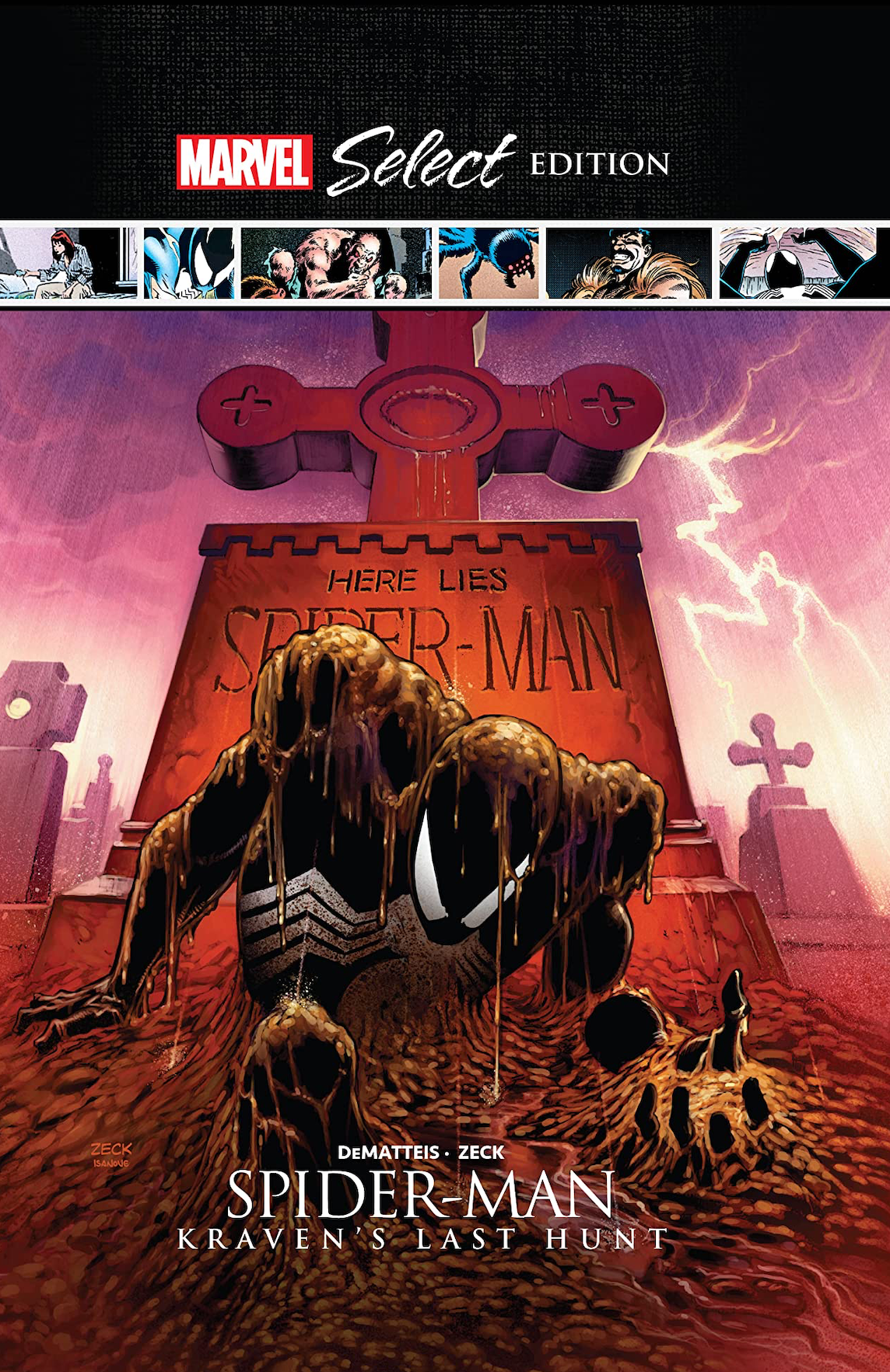

For the uninitiated, Kraven’s Last Hunt—written in 1987 by DeMatteis and illustrated by Mike Zeck—follows Spider-Man villain Kraven the Hunter (aka Sergei Nikolaevich Kravinoff) into a spiral of mental illness and obsession. But it’s not enough for Kraven to simply defeat Spider-Man, who he’s turned into a symbol for everything wrong in his life. To get revenge Kraven must also become his nemesis and literally assume the mantle of Spider-Man (costume and all) after burying the real webslinger alive. Having accomplished his goals and defeating Vermin, another Spider-Man adversary, Kraven kills himself—an ending that shocked the comic book world.

With Marvel’s Select Edition of Kraven’s Last Hunt out this month and news that Kraven might soon join the Spider-Man cinematic universe, it seemed like a timely opportunity to talk with DeMatteis in a wide-ranging conversation about Kraven, suicide, the nature of death in comics and Hemingway’s impact on this masterful, disturbing story arc that helped define his career. - Robert K. Elder

Robert K: Elder: What was your first exposure to Ernest Hemingway?

J. M. DeMatteis: Weirdly, my first exposure is exactly what we're here to talk about: How Hemingway died. I remember my friend telling me about his suicide. I knew the name because he was just such a mythic figure—you didn't have to read his books to know who Hemingway was: the macho guy, the hunter, the whole thing. And I remember my friend explained to me that this guy stuck a rifle in the mouth and blew his head off. And it's shocking at any point. But when you're a kid, and you hear something like that, it’s absolutely haunting...and it always stayed with me.

One quick bit of clarification here. Most biographers say that, in 1961, after battling chronic depression, multiple brain traumas and previous attempts to kill himself, Hemingway put a double-barrel shotgun to his forehead and tripped both triggers. There is some disagreement about the details, however. In 1999, biographer Michael Reynolds wrote that Hemingway put the gun in his mouth. That account is no less horrific, however, though it’s strange how the image of a gun in his mouth took hold in the culture—even before Reynolds wrote about it. No one was in foyer with Hemingway when he died, however, and there was no autopsy.

It must have just trickled into my unconscious mind and just marinated there all those years. When I was working on Kraven, it just seemed like a natural ending. I don't even know if it was completely conscious.

It's horrifying. And yet, it's fascinating. It's like the traffic accident that you can't look away from. Suicide in general is always baffling. And to a kid, it's even more baffling. And then it's so graphic, and it's so grotesque.

And yet it's the same thing that draws us to horror movies and our fascination with the dark aspects of life. We get fascinated because we want to understand it and absorb it so that we can make sense of the world. I think that's why we get fascinated with these horrible dark things. Because life has its fair share of horrible dark things.

There’s a value in writing villains and, for me, one of the most interesting things that I came to realize over the years is that by looking at the so-called evil person, and really looking at them in three dimensions, and the fullness of who they are, you can have compassion for them. It brings a level of understanding through the fictional interaction that we can then bring out into the real world. By looking into them, you can come to some kind of understanding: “Why would a human being do this? Why do things like this happen?”

That's why we’re writers, we’re unafraid to delve into those dark waters in our own psyche and in the world around us.

Why do you think that the Kraven story has resonated over decades?

There are a number of factors. For me personally—it's gonna sound a little odd—but I was going through some of the most difficult times of my life while I was writing that story. I don't have to get into all of it, but I was going through a very painful divorce and then, as often happens in life, one trauma kind of uncorks another.

And everything I was going through—all my pain and struggle—was in that story. I was Peter Parker in that grief, trying to claw my way out of the grave. I was also Kraven, on the edge of madness. The emotions are so authentic, that I think people responded to that.

But I think the real reason is, always inexplicably, the chemistry between writers, and artists. If Mike Zeck hadn't drawn that story—even if I'd written every word the same, if every panel was the same—we might not be talking about the story today, because there was a chemical click between me and Mike. You know, we'd worked together for three years on Captain America, and it was as if we had been in the gym, working those muscles together. And so by the time we got to Kraven, we were completely in shape.

There are all these accidental elements, too: the fact that Spider-Man was in his black costume, the fact that Peter and Mary Jane had just been married. That added a whole other emotional layer to the story. So all these elements came together at the same time to create this resonance in the story, elements that were certainly beyond my control. The story became something bigger than the individual parts.

This story was published in 1987, a year after Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns and just as Alan Moore’s The Watchmen was wrapping up. What was happening in the comic industry that gave rise to this more mature, darker storytelling?

I think it was that decade, because the ’80s was the decade when things really exploded. New formats were coming in and publishers were allowing you to push the barriers in different ways that have never been pushed before.

I think everybody was excited and inspired each other. And seeing what, for instance, Frank Miller was doing with The Dark Knight gave me permission to push. For me, the thing that really did it was working on Moonshadow for Epic Comics, where I could step outside of those constrained superhero universes. That was where I found my voice as a writer. That's where I could sit down and not write a “comic book.” I could write as if I was writing a novel. And that freed me of all these preconceptions, 90% of which I imposed on myself because I thought, “This is what you're supposed to do when you write a comic.” I went from Moonshadow to Kraven’s Last Hunt. So having broken those shackles, Moonshadow freed me to write Kraven in a way that I could not have written before.

I know that this story didn’t originally start out as a Spider-Man story. You first pitched the concept as an Avengers story about Wonder Man and his half-brother, the Grim Reaper. Later, it morphed into a Batman/Joker pitch, then a Batman/Hugo Strange story. But did any of those stories end in suicide?

I don’t think so. But it’s been so long that I can't swear to any of this. But my feeling is to go right back to where we started. It was that “Hemingway Great White Hunter” thing. It seemed like an inevitable ending for Kraven to go out in a Hemingway fashion.

On the surface level, Kraven’s whole image is wrapped up in this macho idea of being the Great Hunter—the embodiment of that macho male stereotype—and Spider-Man is the game that has eluded him.

The other level is the deeper psychological layer of Kraven. In his childhood, he was brought up essentially like a prince in Russia in those so-called glory days of the tsar, and everything was taken away from him. And then his family comes to America and his soul is crushed. His mother dies in an institution. His father, from his point of view, was just weak and miserable. In his madness, he's looking for something to hang all his pain and all his struggle and all his suffering on.

And so Spider-Man becomes the embodiment of every frustration in his life. And he thinks that in destroying Spider-Man, or at least proving himself superior to Spider-Man, he would find the ultimate victory.

The great hook of the story that I can still appreciate all these years later is, “I'm going to kill you, but I'm going to bring you back so you can know that I killed you, and that I'm better than you.” [laughs]

And that's why, in his own mind, Kraven was at peace in the end, because, “I proved I was better than the Spider.” But the whole idea of the Spider is an idea projected from his own mental imbalance. The Spider doesn't exist, he just proved himself better than something that is only a projection of his own madness.

I’m sure that Kraven’s origin, in part, comes from that old short story by Richard Connell, “The Most Dangerous Game,” about the Russian aristocrat who hunts human beings for sport. Kraven is a combination of that and Tarzan/Jungle Jim. I think this is the most toxic part of the Kraven story is that “white guy in the jungle” thing. If I was writing that story today, I would address that directly and more sensitively, but that's another issue for another time. The whole idea is that Kraven ended up somewhere in the African jungle because he rejected the civilization that raised him.

But that's also Hemingway. He loved Africa and even wrote a book in 1935 about his safaris there, The Green Hills of Africa. For most of his life, Hemingway lived in remote places. All his life, he loved hunting and fishing and one of his favorite writers was Ivan Turgenev, a Russian realist writer who wrote about hunting. Hemingway also moved to Idaho because he said it reminded him of the terrain in Africa.

Oh, that's interesting. There's a little bit of that in Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness. If you really explore that, there's a lot of racism—where we’re civilized and they're the primitives, even when it's presented in a noble way. The idea that one culture is “civilized” and one isn’t—is a fairly toxic one.

Coming back to Hemingway, what was the larger cultural context in his death? What did Hemingway’s suicide mean to you? Was there symbolism in it?

I never really thought about that. I thought about that more in this conversation than I have in my entire life. I was probably somewhere between 9 and 12 when I heard the news. It was a shock.

I grew up in an era where there were a lot of shocks. When I was in the fourth grade, the Cuban Missile Crisis happened, and I literally thought that, within the next 24 hours, we were all going to die in a nuclear holocaust. That leaves an impression. The next year, Kennedy was assassinated. And as a kid, it's like these things that you could never conceive before had happened.

And hearing about Hemingway’s suicide, although on a much smaller scale, is one of those things that suddenly opens a window and says, “You know, life can be really weird and really dark and really shocking.” People can do things that just seem so inexplicable. And I think that's why those things stay with us. And that's the thing that really did it without me being Hemingway aficionado, having only read A Farewell to Arms and The Old Man and the Sea.

And yet, that imagery stayed with me for years. Maybe Hemingway’s suicide became a symbol of that dark, incomprehensible part of living—things that, no matter how much we try to explore or explain, will always have a level of mystery to them. But I do not in any way see Hemingway's suicide, or Kraven’s, as a noble death.

What sort of conversations were you having with your editor, about either the depiction of mental illness or suicide? For me, I first read this in 1987, when I was 11. It was my first exposure to the concept, let alone the visuals, of suicide.

I hope I didn't traumatize you. The amazing thing about that story was: I pitched it, they loved it, I wrote it. That basically was the process on that book. The only note I remember coming back was from Jim Shooter, who was the editor-in-chief when we first started working. It was one panel with Vermin. Because he was a cannibal, there were a lot of bones in the panel and Jim was like, “Can we take out a few of the bones?” and that's the only note I remember.

You returned to the storyline in 1992 with the graphic novel Amazing Spider-Man: Soul of the Hunter. Was this because of some of the criticism you received over the suicide?

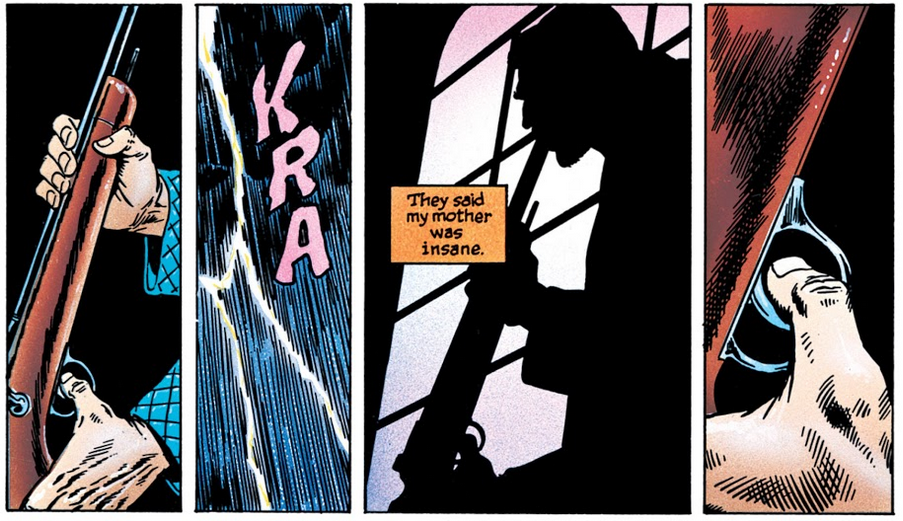

It wasn’t overwhelming, but Tom DeFalco, who was Marvel’s editor-in-chief after Shooter, called me up. He got a letter from a suicide prevention group saying that they were very upset that we glorified suicide. Well, in my mind, we weren't glorifying suicide. In my mind, it was very clear that Kraven was a tragic figure, who was mentally ill. We set up the whole thing with his backstory. His last words were, “They said my mother was insane,” and he pulled the trigger.

But when you say that’s glorifying suicide, I have to step up and say, “No, no, no, no, that interpretation is so far off the rails.”

And I'm sure there were people that interpreted that as a noble death. But that was not the intention at all. So when I heard this, being the person that I am, with my Jewish / Italian guilt, I felt terrible. So I thought, “Let's see if we can do a story that addresses that.” And so that's where Soul of the Hunter came from, which was really all about Peter’s guilt. Peter, being who he is, has got to feel, “Why couldn’t I have gotten back sooner? I could have stopped it, I could have done something.” It's really about Peter dealing with his guilt over that suicide.

How did you feel about Marvel resurrecting Kraven in 2010’s The Grim Hunt?

You know, they waited so long. It was at least 20 years when they brought him back. I believe that Joe Kelly wrote that story, and I thought they did a good job. But I mean, here's the truth: Would I have liked him to stay dead forever? Sure. But it's comics. Everybody comes back.

I’ve brought back characters that may have pissed off some other writer, but it's just the nature of comics. Everybody's playing in the same sandbox. Everybody's playing with the same characters. I may undo someone else's story. Someone may undo my story or revamp it or reboot it or whatever. It's just the way it goes. The question is, “Did they do it in a way that works?” And I thought they did.

I was just talking with a friend about this. It’s hard for comic book characters — who are now movie franchise characters — to have real life-and-death consequences because at a certain point, they aren’t characters: They are ATM machines. They exist to make money, and it’s hard to kill off IP (intellectual property).

I just finished my writing class over the weekend, I was saying the same thing. There's a very big difference when it goes from being a character to IP.

Then there’s the nature of serialized storytelling and the fact that it's Spider-Man. And you know, this comic is going to be coming out 10 years from now. He's not going to be dead. He's just not. That's why, when you think about an event like the Death of Superman, only the civilians—and some really hardcore fans who should know better—believed that it was true.

People who were lining up to buy the Death of Superman comic book—because they thought it was going to be worth a million dollars—didn't know the first thing about comic books. When you plaster the message on the cover that says, “This story will change everything!”— when that's plastered on a cover every month, it's not changing everything. It's just not. And that's the problem of serialized storytelling.

And that's why I always say: Just tell really good stories. You don't have to change everything and tear it down and reboot, because what happens inevitably is: they tear it down, they rebuild it, and they bring all the old elements back. Over time, all those elements come back, they may come back in a slightly different form, but they all come back.

You've had this long, illustrious career and it’s been a joy reading you over the decades. I have a personal affinity for Moonshadow, but is the Kraven story the one you're asked to talk about most?

It's one of them. When I go to conventions, I feel like a third of what I sign is probably Kraven’s Last Hunt. But a third of what I sign is on the exact opposite side of the spectrum, the Justice League stories I co-wrote with Keith Giffen. What amazes me when I look back is that I was writing those things simultaneously. I was writing this incredibly dark Spider-Man story and these very funny superhero comics at the same time.

Honestly, it's not my favorite story. It's a story I'm proud of and I think it's an excellent story. But if I was listing my favorite stories, it wouldn't be in the top two or three, for sure. If I was listing my favorite Spider-Man stories, then maybe it would be number two or three, but not number one. That said, I’m proud of it and honestly very moved that it’s lasted this long, that people are still reading, and discovering it.

OK, let’s go on the record then. What are the favorite stories you’ve written?

The years that I did on Spectacular Spider Man with Sal Buscema (1991-1993). I'm really, really proud of that, especially “The Child Within” arc (issues #178–184), which was a semi-sequel to Kraven because it brought back the Vermin character. It was one of the first mainstream stories that dealt with child sexual abuse in a direct way. In the course of those two years, there was a big Harry Osborn / Peter Parker story that ended with the climax in Spectacular Spider-Man #200 with Harry's death.

In terms of other stories of mine, it’s the more personal stuff. It's Moonshadow, it’s Brooklyn Dreams. There’s a very obscure fantasy thing that I did with artist Mike Ploog called Abadazad that we did first as a comic for CrossGen, then as a series of children’s books for Hyperion. And then I’ve got that whole universe of stuff with Keith Giffen, which is like a whole other career.

Not in any way to negate Kraven; it’s up there. I think one of the reasons that it’s harder for me to appreciate than the audience is because it was written at such a painful time in my life. And it’s like all that pain is in the story. So, I don’t need to go back to that, y’know? But I do understand what people see in it.

Kraven is a gift that keeps on giving. Back in the 1980s, when I wrote the story — I thought it was a good story and that was pretty much the end of it. You didn't think about books being in print continuously for 30 years. That's the weird thing that happens with the audience and that has nothing to do with me. It has to do with the chemistry between the audience and the story. And I’m very grateful for that.

Robert K. Elder is the author of 15 books, including Hemingway in Comics, out now from Kent State University Press. J.M. DeMatteis and Mike Zeck’s Kraven’s Last Hunt is out now in a new Marvel Select Edition hardcover. For more information about Elder, visit robertkelder.com.