The history of comics is replete with heroes, flamboyant saviors known for outsize exploits. But one character and his creators played that role for real, as revealed in a new Paris exhibition.

At its center is Belgium's Spirou, a character who turned 85 last month. Thanks to the genius of André Franquin, Spirou is as famous in Europe as Tintin. He has his own vehicle, Le Journal de Spirou, his own animal sidekick (Spip the squirrel) and, in place of Captain Haddock, a pal named Fantasio. But it's Spirou's early work during World War II–stepping out of his strip to join the resistance–that animates Spirou dans la tourmente de la Shoah ("Spirou in the Turmoil of the Holocaust").

The exhibition is based around a graphic landmark, the artist Émile Bravo's L’espoir malgré tout ("Hope Despite Everything"). Issued in four volumes between 2018 and 2022, it represents 15 years of work and, in 2022, won Angoulême's Prix de la Série.

Bravo's remarkable series was informed by actual people who, in his books, appear obliquely. Sometimes it's through a name, like that of the young resistant "Victor". Other times, their echoes turn up in characters: married Jewish artists who live a clandestine life; "good" and "bad" Catholic priests who happen to share a church; a young woman with a perplexing string of boyfriends. This exhibition unveils the lives behind those clues. It also introduces Spirou's subversive editor and his motley troops. They included not just writers, artists and editors, but a single mom, a sociologist - and a puppet. Led by this marionette, the crew defeated actual Nazis.

The show is notably well-conceived and carefully staged. You don't need to know either Spirou or Bravo's series and, like both of them, the contents are family-friendly. (For children, there's a special cartoon-led, guide.) Best of all, it's completely free of charge.

Bravo's L’espoir malgré tout series first made waves for its debut cover. This featured the Spirou fans have long known, clad in his signature scarlet uniform (Spirou began his life as a bellhop). But here he was pictured at a remove, behind marching black boots which occupied the foreground. The cover was announcing Bravo's bold ambition: a 330-page series that immersed the cartoon innocent in World War II. From its start, the series carried allusions to modern events, such as the world's migrant crisis and its demagogues. But it also evoked some lost controversies, including what Le Monde termed "the troubled past of the era's most promising artist." This, of course, was Hergé, at whose expense Bravo makes a lot of gags.

The world Bravo's Spirou and Fantasio face grows bleaker and bleaker. Yet these books are never history with a capital "H". For, as the series continues, its classic roots are more and more evident. Although born in Paris, Bravo is steeped in Belgian comics and he is masterful at marrying laughs to high adventure. His heroes' escapades take their cues from reality (one major source was a Belgian banker's wartime diary), but Spirou and Fantasio keep to their usual antics, just as they do their traditional rapport. The books' wonderful colors, which are by Fanny Benoît, add a winning vintage aura. All in all, it's a Franco-Belgian classic.

Bravo is especially careful to avoid exploitation. Rather than personified in characters, his Nazi menace is signaled, page by page, through a growing darkness. The only Nazi face you see turns out to be a Belgian, and there are none of the usual WWII clichés. There is no fetishizing of uniforms, nor any wallowing in human abjection. Says the artist, "Nazis were never the point. I'm a children's author and I'm interested by how a conscience is formed, how the process of what you encounter shapes you. I wanted to show the importance of opening up to the world, how you learn to listen while retaining doubts. That's what educates you and that's how you grow."

"Also," he adds, "as a kid I learned a lot from Charlie Chaplin. He taught me laughter and tears are never far apart."

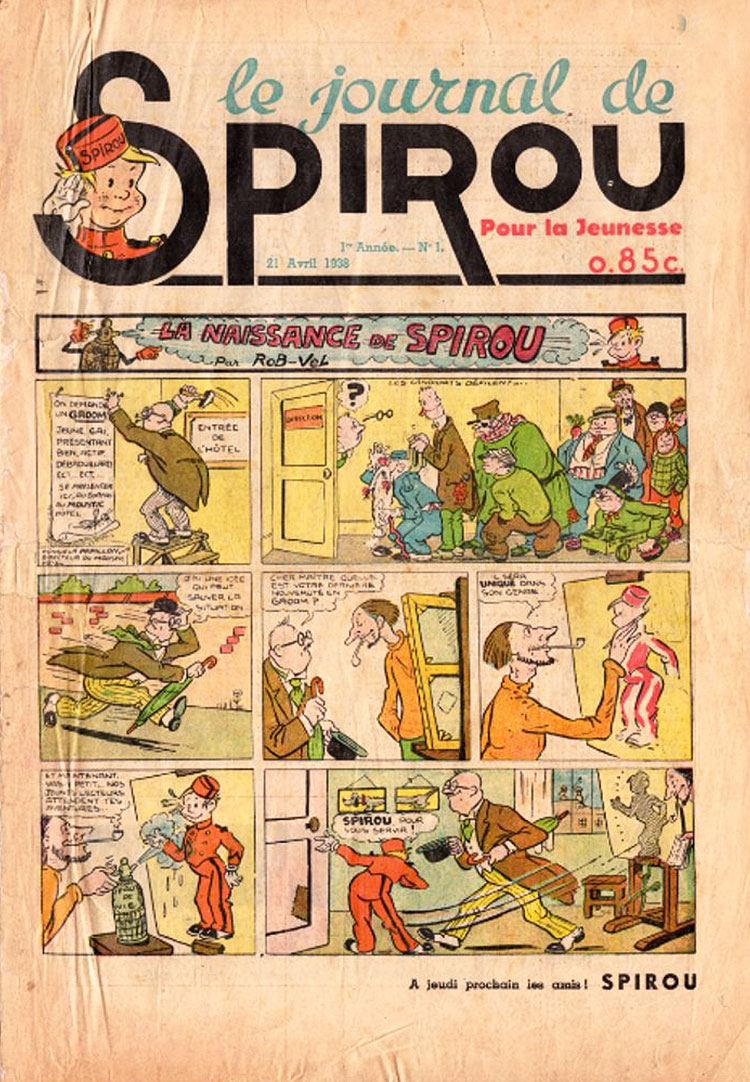

Spirou, despite his childish looks, was never normal. His very first move was to break out of the frame. In 1938, on Le Journal de Spirou's first cover, he was drawn into "life" by a bearded artist. Once the canvas was spritzed with "eau de vie", the sketch of him came alive and leapt into the magazine. The hirsute cartoonist depicted was Luc Lafnet, a close pal of Spirou's creator Robert Velter ("Rob-Vel"). Lafnet drew many comics written by Velter's wife, Blanche Dumoulin, who signed herself "Davine". While this trio of friends functioned as a studio, it was Velter who signed the Spirou strips.

Published by the Catholic family firm Dupuis, Le Journal de Spirou was based in Belgium's Marcinelle - a suburb of working-class Charleroi. There, in an uncle's kitchen, Jean Dupuis founded his print works. He aimed his weekly Journal at young children, but it produced many comic legends: Jijé (Joseph Gillain), Franquin, Maurice Tillieux, Morris (Maurice de Bevere), Will (Willy Maltaite) and Peyo. They became known as the School of Marcinelle and, in the 1950s, it was Spirou artists who created la ligne claire's rival, le style atome. Le Journal de Spirou brought the world numerous classic characters, too, such as Franquin's Gaston Lagaffe, Tillieux's Gil Jourdan, Peyo's Smurfs and Morris' Lucky Luke.

It was Jean Dupuis (1875-1952) who baptized Spirou. Literally, the character's name is Walloon French for "squirrel". But, as Dupuis explained, "To us, a 'spirou' means a kid of 8 or 10, a boy who's sometimes boisterous or absent-minded. Yet he's a boy whose teachers won't complain because, as well as he can, he always does his duty." He was insistent that Spirou stand for moral good.

The Belgium that welcomed this character was largely Catholic, and the church applied controls over almost anything that dealt with children. It was a very conservative, royalist nation, and one that retained a colonial domain in the Congo. Anti-Semitic views existed throughout its society, and Dupuis' early publications were no exception. But in 1940, when the Germans invaded, Belgian print was flourishing. The country had 78 daily papers, 350 weeklies, 300 technical mags and 9 publications for children.

There was always drama in Spirou's early life. He was not even two years old when Poland fell to the Nazis. Within days, Rob-Vel was drafted by the army and, within weeks, he had been captured. Less than a month later, Lafnet died of cancer. Left to manage Le Journal de Spirou by herself, Dumoulin called on the only demobilized artist she knew. He was Joseph Gillain, better known as "Jijé" (the French pronunciation of his reversed initials). Jijé was 25 and already seen as a maverick. Yet he was deeply Catholic - two of his brothers were priests and two of his sisters nuns.

Jijé had been trained to decorate churches, and he could handle anything from metal to frescoes. He also had an original mind and liked to work in different styles. "From every point of view," says the comics historian Christelle Pissavy-Yvernault, "Jijé was a force of nature."

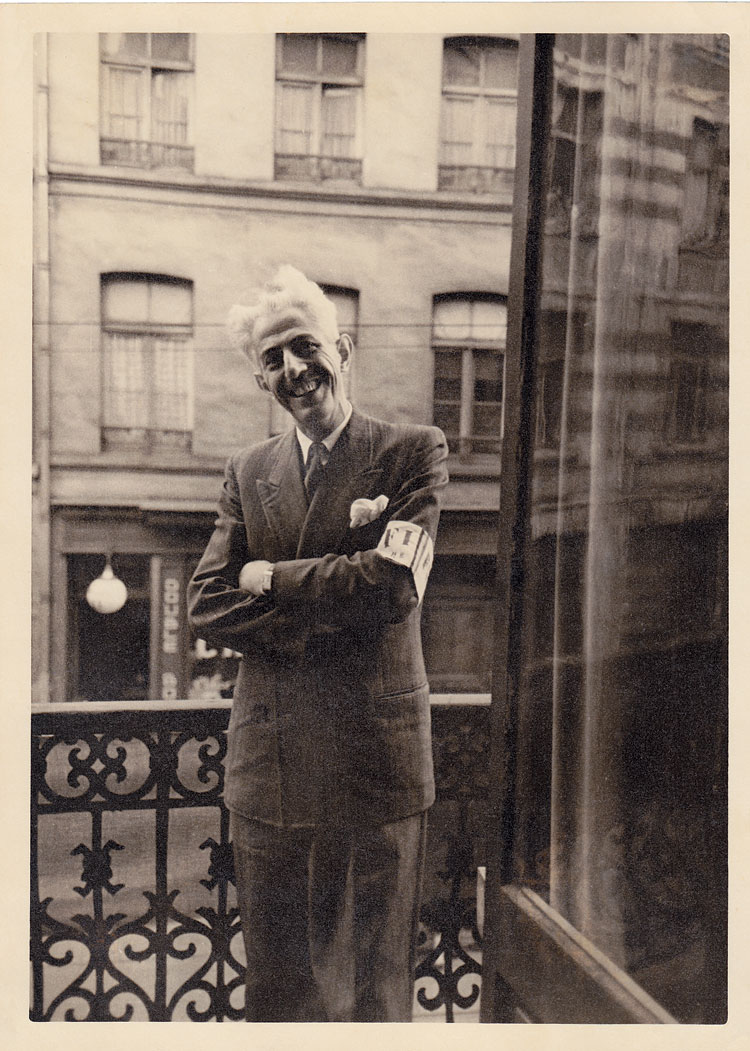

Gillain often knocked heads with Le Journal de Spirou's editor, the thin and mustachioed Jean-Georges Evrard. Evrard, 39, was known at work by his nom de plume Jean Doisy. He had been at the firm for seven years and, unlike his colleagues, was a fervent communist. With his close friend, the journalist Emile Hambrésin, he had co-founded a ligue contre le racisme et l'antisémitisme. By 1939, Doisy was also part of a Catholic group that helped Jews out of Germany.

Doisy had two public roles at Le Journal de Spirou. He wrote in the magazine as "Le Fureter" (a fureter, or "ferreter", also means "snoop") and he ran the "AdS" or Amis de Spirou ("Friends of Spirou"). Every kids' magazine had such a fan club, but within a year of its launch, Spirou's boasted 5,000 members. All had access to a secret code, created by Doisy and used only with them. The editor even invented a character to "help" him, a rambunctious fellow he dubbed "Fantasio". In 1949, Jijé made Fantasio part of Spirou's strip.

The 1940 occupation was not Belgium's first. During World War I, Germany had ruled the country between August 1914 and November 1918. This caused a near-total economic collapse, and it was a time of widespread suffering. WWI killed 40,000 Belgians, and it wounded another 70,000, many of them horribly maimed. Over 120,000 residents were deported, serving as forced laborers in Germany. This was the world in which Jean Doisy grew up.

Twenty-two years on, the same thing happened again. This time it took only 18 days; invaded on May 10, 1940, Belgium surrendered to the Germans on May 28. Every publication was then face-to-face with censors, and the closed borders caused a serious paper shortage. Being a World War I resistant who feared reprisal, Jean Dupuis fled to London. He left his sons and son-in-law to run the firm - which, thanks in part to Doisy, kept on going.

Le Journal de Spirou diminished in format and pagination. But every week it still trumpeted "Spirou's values". Those pages, allegedly for children, rapidly filled with coded resistance messages. Spirou's AdS also enjoyed a sudden boom, and by 1945 it numbered 65,000. Many of these new "Friends", however, were not children. They were teenage youths and, thanks to Doisy, resistants.

Doisy was a recruiter for Belgium's Front de l'Indépendance. (René Matthews, Jean Dupuis's son-in-law, was also a member.) The underground "FI" was founded by communists, but its members varied from leftist Catholics and social liberals to militant Christians. In 1942, after the first acts against Jewish residents, the FI helped form a Jewish Defense Committee (Le Comité de defense de Juifs). In addition to working with all these groups–not to mention editing Spirou–Doisy was running a secret journal. This was entitled Pourquoi pas? ("Why Not?"), and it appeared on paper pilfered from Dupuis. Outside the office, he was equally active: hiding strangers on the run; planting propaganda; and smuggling explosives.

Between 1940 and 1941, most children's journals received enough paper to publish. The Dupuis family also had hidden stocks. But once pro-Nazi youth mags appeared, the occupiers started shuttering their competition. Because of his radical views, Doisy was closely watched, and the Gestapo even called on him at home. This ordeal left the editor so shaken that, overnight, his dark hair turned white. Yet he continued exactly as before.

The Nazis closed Le Journal de Spirou in 1943. For its star character, this was the start of what proved a restless history. After the war, Spirou went on to be drawn by a range of artists. Jijé passed him on to Franquin, who was succeeded by Jean-Claude Fournier. Fournier has been followed by a parade of others, each of them seeking a personal rendition. "Spirou is now almost like a franchise," Bravo told France Culture. "But there's a problem for everyone who takes him on, which is the 1946 Spirou André Franquin imagined. No one can really follow such a genius. All you can do is accept the fact with grace."

At first, when Dupuis asked him to join the roster, Bravo said no. "I thought, 'This is Franquin's world and no one touches Franquin.' But then I started to think, 'What about the Spirou who preceded Franquin? Why not explore his youth?' After all, I grew up with Spirou and Tintin. I had nothing in common with American comics and those huge men in ridiculous clothes. But, as a kid, I was really intrigued by Spirou… Why was he always wearing that bellboy suit? How did he come to work in that hotel? How had he ever met someone like Fantasio? I always wondered what had turned a jolly-looking mascot into Franquin's Spirou… a character with a conscience and such a wily mind."

In the end, those questions about "what had happened" seduced him. Bravo became one contributor to an homage, a special collection of Spirou albums by different artists. Each book was called Spirou par… or "Spirou by…" Bravo called his Le Journal d'un ingénu: "Diary of a Simple Soul".

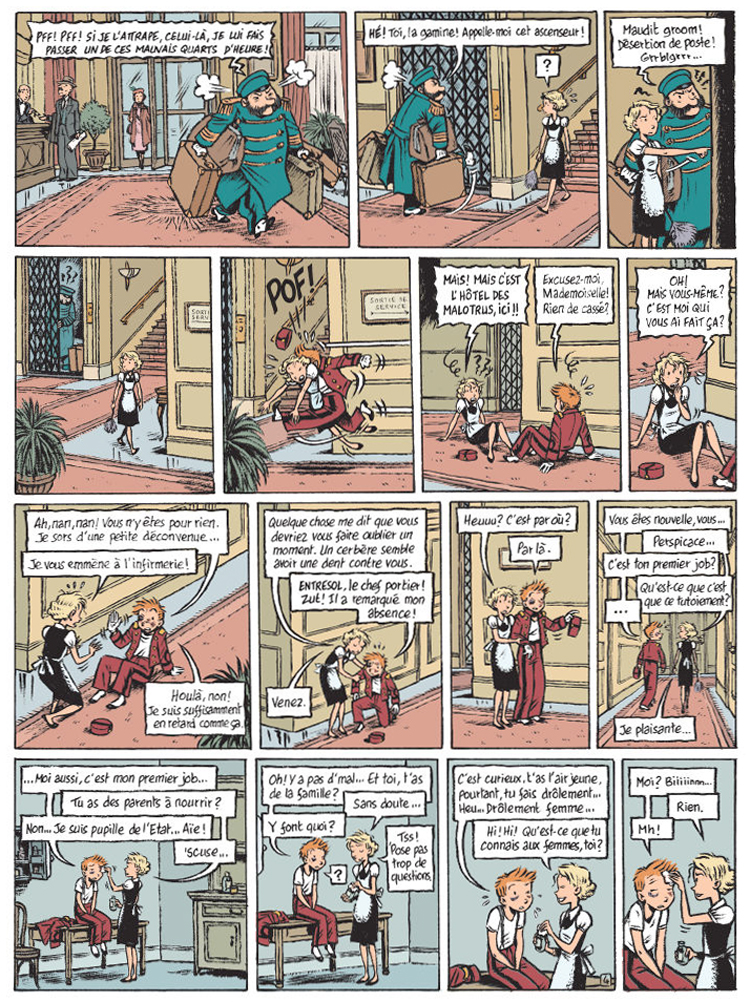

Le Journal d'un ingénu appeared in 2008, but its story took place 70 years earlier. Staging this tale in the run-up to WWII helped Bravo answer the questions he had posed as a kid. "I started out with the date and what's about to happen. But I needed something to wake Spirou up as a person. Then I realized that, for someone as young as him, it would probably be a girl. Because falling in love can be your first revelation. So I started to think about a female character. Right away, I knew she would be political. Because here we were in 1938."

That she would be a communist, he adds, seemed evident. ("I had to get Spirou out from under his 'Belgitude', his Catholicism and all that.") So he created a Jewish "fiancée", a fragile blonde named Kassandra Stahl. Born to a Polish mother and a German father, Kassandra was raised in Soviet Ukraine. Because Spirou is working class, the artist made her a domestic, a fellow employee at Spirou's "Moustic Hotel". Behind the scenes, however, Kassandra is a Soviet agent.

By Journal d'un ingénu's end, Kassandra has disappeared and, in the L’espoir malgré tout series that followed, she hardly appears. Yet, for Bravo, she provides the common thread. "It's his search for her that keeps Spirou going. All our lives are constructed by chance. So, while Spirou meets Kassandra accidentally, she is the thing which brings him into the wider world. It's her character who makes geography human."

Bravo's "Diary" supplied Spirou's missing past. The book revealed him to be an orphan named Jean-Baptiste, placed in the bellhop job by clerical carers. Since another "Jean-Baptiste" already worked there, he took the name of his pet squirrel. This squirrel–initially Spirou–then became Spip. Spirou met Kassandra and Fantasio through work, where each was trying to get something out of him. Kassandra wanted intelligence for the USSR, while Fantasio, a journalist, was on the lookout for gossip. (Amusingly, Fantasio was employed at Le Moustique, which was another of Dupuis's real publications.)

Using fiction to animate fact has been done before in comics. What makes Bravo's books so singular is their inventiveness. For example, in order to fool the Gestapo, Spirou has to shed his telltale uniform. The disguise Fantasio rustles up–a long coat, flat cap and baggy plus-fours–turns him into Tintin's eerie double. This (like Spirou's irritation with the kids who always cry "Tintin!" at him) is recurrently funny. But, while many nods and winks like this lighten the story, they also deepen it. What seems to be–what is–a tale of WWII, becomes a reflection on illusion itself.

Says the artist, "Having Spirou dress as Tintin so he can pass unnoticed was just my little joke. But Tintin certainly made it through that time without a problem! In my version of the era, Spirou really exists. Tintin remains just a paper hero."

Bravo's Spirou keeps the character Jean Dupuis decreed; when Fantasio takes up arms, he refuses. But his "simple soul" is nonetheless deeply changed. Although Spirou keeps on dreaming of Kassandra, by the story's end she is lost to him. Readers know she survives the camps and reaches Palestine, but it's clear events have severed her from Spirou. "The fact he loses Kassandra," Bravo told Le Monde, "is the sign Spirou will never grow up. He's going to spend his life in waiting - which is why he retains the red uniform. It's his homage to Kassandra's communism."

Bravo is 58, a self-taught independent. In 1992, along with David B, Lewis Trondheim, Joann Sfar and Emmanuel Guibert, he co-founded a studio, the Atelier Nawak. He was also part of another studio, the Atelier des Vosges, which included Marjane Satrapi. In 1993, Bravo and Jean Regnaud created Les véritables aventures d'Aleksis Strogonov ("The True Adventures of Aleksis Strogonov"), a series that traversed the Russian Revolution, fascism and the Balkan conflict. Since then, he's also been behind the interstellar series Jules, a six-volume epic that won the Prix René Goscinny for comic writing at Angoulême. In addition to all his children's publishing, Bravo has a separate career in illustration.

There's a reason his personal books are so political. Bravo's father was a Spanish Republican and fought Franco during the civil war. But when he entered France as a refugee, he was interned in a camp for foreigners. He managed to escape - only to endure the German occupation. Says the artist, "I was very affected by his experience and I've always had an interest in that era. Everyone who lived through it speaks about the same things. It's just always hunger, cold and fear. It was less about heroics than about daily endurance."

But something else helped shape L’espoir malgré tout. This was the appearance, in 2013, of Christelle & Bertrand Pissavy-Yvernault's La veritable histoire de Spirou 1937-1955 ("The Real History of Spirou 1937-1955"). The two historians unveiled a wartime story that, before their research, had largely been unknown.

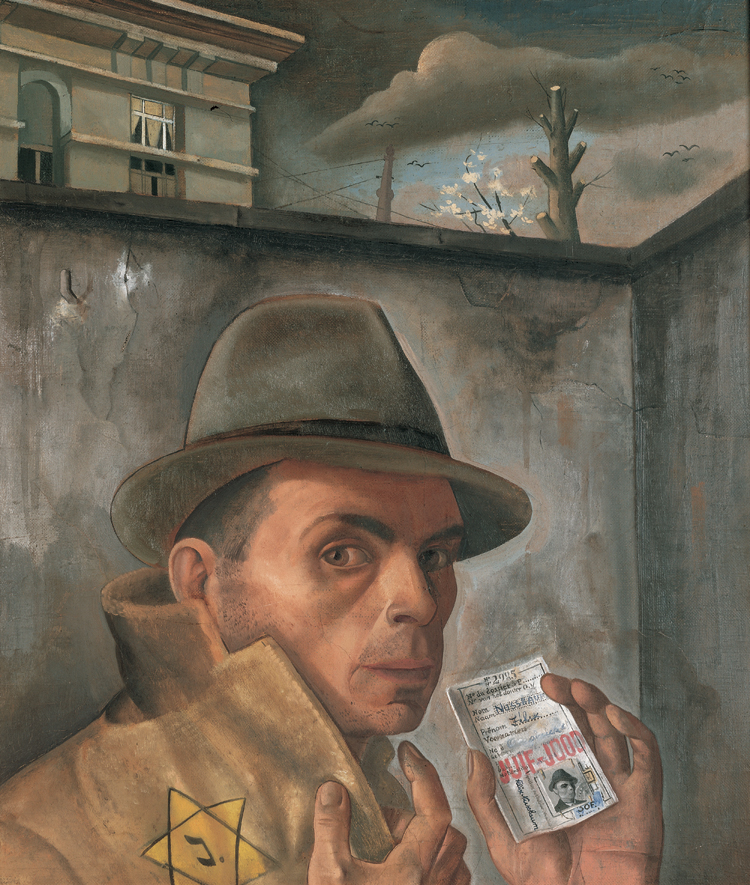

Bravo's choice to continue his Spirou saga was in part decided by their revelations. But imagining Spirou's start in life was one thing, and plunging him into World War II was something different. How could a children's icon ever confront the Holocaust? Bravo found his answer only by discovering a pair of Jewish artists: Felix Nussbaum (1904-1944) and Felka Platek (1899-1944). Before this pair were deported to their deaths in Auschwitz, they had lived as refugees in Belgium.

Nussbaum was German and his wife was Polish. Both were accomplished painters who, even in hiding, managed to continue working. The Spirou dans la tourmente de la Shoah exhibition contains many of their pieces, and those by Nussbaum are mostly self-portraits. They illustrate the collapse of their maker's psyche and reflect the terrors felt by Belgium's Jews. Bravo's Spirou befriends "Felix" and "Felka", but their family names are never given. Still, Bravo follows their actual story to its end. This is not pictured, but conveyed through a depiction of Nussbaum's final painting.

The two artists seem almost present in the show. Nussbaum's painting of his studio, for instance, exudes a sense that he has simply left the room. Platek's portrait of a female friend is similar; it brims with shared laughter and life. Yet, only inches away, the pair's solemn faces peer out of photographs on their Jewish identity cards.

While this is a poignant sight, it's only one of many. Bravo's original art boards sit alongside Jijé's wartime art; photos of Le Journal de Spirou's staff flank a yellow star. There are lists of deportees typed on crumbling paper, and eulogies from Spirou that hail "Friends" who perished. There's also a small and fading note scribbled in pencil. This reads "It's 5 in the morning and they've come for us in our beds. No idea why. Farewell, Boris."

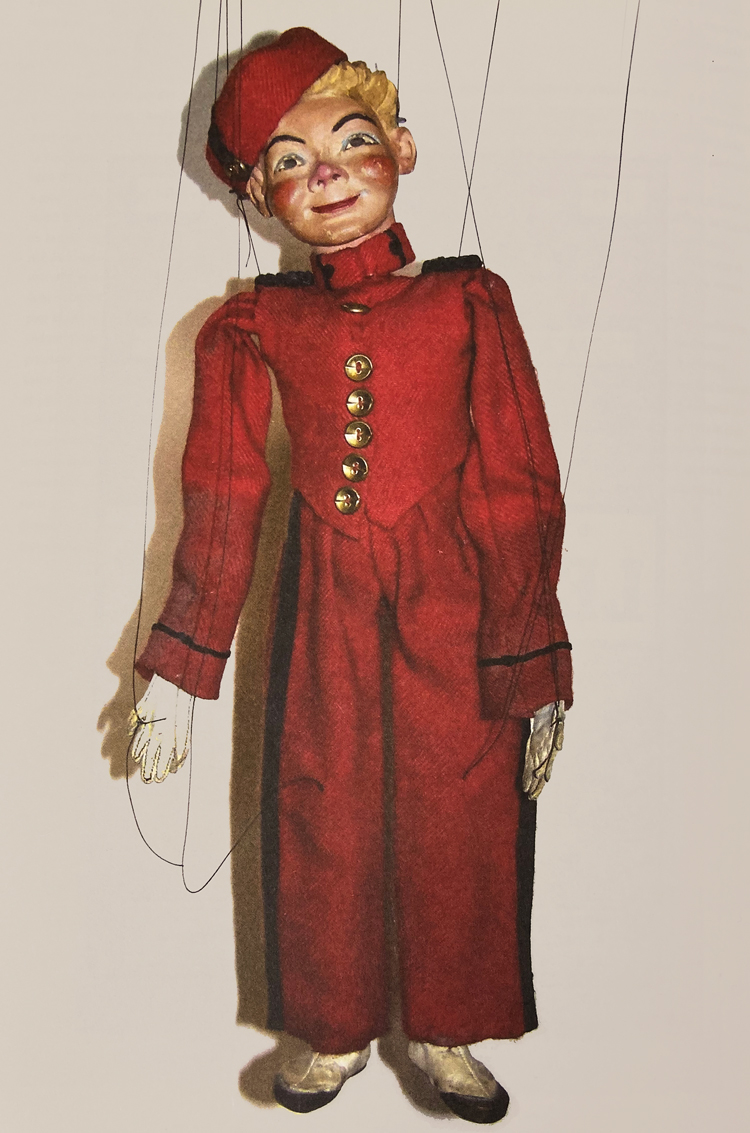

Yet the show's presiding mood is uplifting. The exhibition's essence resides in a puppet: a colorful 3D likeness of Spirou himself. This fantastic figure is a real-life hero whose strange story begins in 1942. That year, on a Wednesday in July, Doisy and Hambrésin lunched with Hertz Jospa. Jospa, also a communist, had co-founded the Jewish Defense Committee. Now, under the cover of superficial banter, he and Hambrésin had a pressing request: Doisy must find them a woman to save Jewish children.

They had assembled a set of homes and churches willing to conceal those threatened with deportation. But the scheme still lacked a female leader - someone they could trust to front the operation. She had to have a credible cover and plenty of nerve; she might well end up paying the ultimate price. As he departed, Hambrésin whispered to Doisy, "Make sure you're honest. Paint the darkest picture possible."

These three friends never met again. Hambrésin was denounced, and died in Germany. But in confiding the mission to Doisy, he and Jospa chose well. Within days, helped by an activist chaplain, the editor found them the ideal candidate. She was a widow by the name of Suzanne Moons, a Catholic single mother. At her home, over a cup of coffee, the modest 41-year old said she would start the following day. As Doisy was leaving, he spied a curious structure in the room next door. It was, Suzanne explained, her son's puppet theatre. André was 19, and crazy about marionettes.

The little cabin provoked an epiphany. Doisy knew Le Journal de Spirou's closure was a matter of time. But if it did shut - could Spirou live on as a puppet? A traveling marionette show would seem innocent. Yet, for moving kids around, it was the perfect ruse. The next day, while Suzanne received her false papers, Doisy introduced André Moons to Jean Dupuis' son, Paul.

Within a week, Spirou launched a special puppet operation. Working with black-market goods and helped by Jijé, Moons had a portable theater ready in record time. He and Doisy called it Le Théâtre de Farfadet ("Theater of the Little Sprites"), and it premiered December 13, 1942. With the Farfadet as cover, Suzanne Moons saved 600 children.

In L'Espoir malgré tout, this idea comes from Spirou. (He is inspired by marionettes in a painting Felix shows him.) But only Fantasio understands its covert role. Says Bravo, "Spirou never catches on; only after the fact does he realize. But his own resistance takes a different form. Spirou resists simply by staying human, by remaining kind even in a climate of hate."

Bravo has Felix and Felka help make the puppets. But–as was actually the case with Spirou himself–they are replicas of the two protagonists. In André Moons' Farfadet, Spirou played the role of an emcee and not a star; he was the host of a comic variety show. But in Bravo's story, Spirou and Fantasio man their actual clones and the dramas they present mirror Spirou's life. These performances feature a black-clad villain ("Grochapo"), constantly pursuing a puppet Kassandra. As the would-be shapers of their own existence, Spirou and Fantasio ensure their wooden Spirou saves her. It's an unexpected mise en abyme - one that feels remarkably unsettling.

Doisy's Farfadet performed all over Belgium. It was run by the Moons family, with help from friends like Jean-Jacques Oblin. Oblin was 18 and ran clandestine meetings through the AdS. He also bombed infrastructure sites used by the Nazis and published a secret journal of his own. This was called Nos Jeunes en Guerre ("Our Kids at War"), and he modeled it on Le Journal de Spirou. Only days after marrying his teenage sweetheart, Oblin was caught and deported to Buchenwald. His new bride was also imprisoned, at Ravensbrück. But Oblin survived - and he later told their harrowing tale in Spirou.

Shortly after the Farfadet's debut, Jospa once again approached Jean Doisy. He had to know what was happening to deportees. The few reports Jospa got told him almost nothing, and this want of information made him fear the worst.

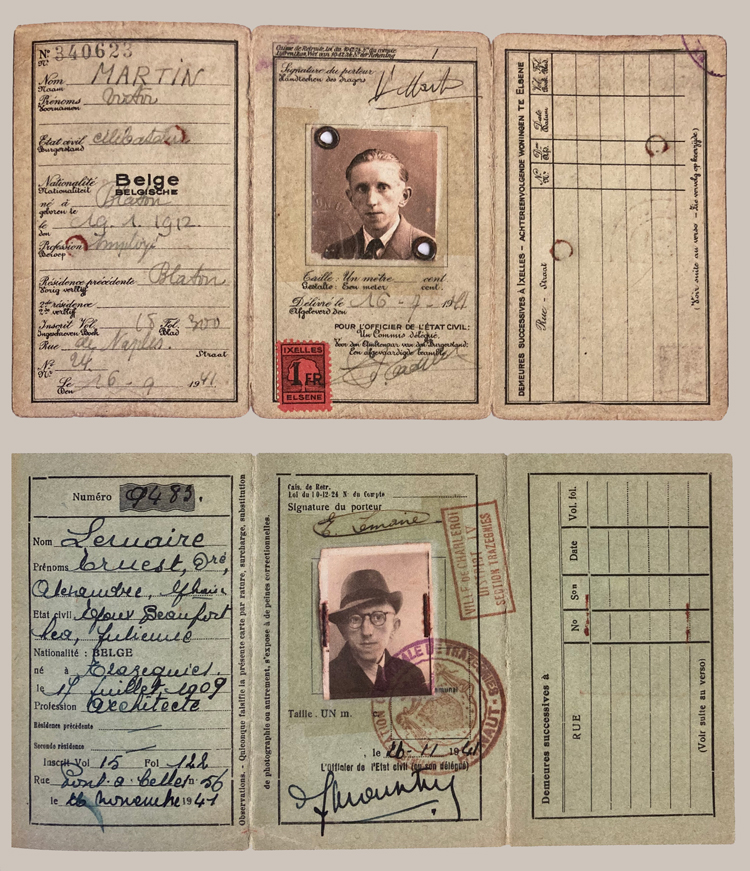

Nothing could be deduced from the trains themselves, for–although this would change–the Jews were leaving in ordinary, third-class carriages. This was also true for those conscripted by the STO (Service du Travail Obligatoire), the forced labor corps. But how "normal" could such targeted expulsions be? Jospa wanted someone to investigate, someone who would actually track the trains to their destination. Dangerous as this would be, Doisy soon found someone: a 30-year old sociologist by the name of Victor Martin. Martin himself knew nothing of Judaism. But he was fluent in German and had contacts in the east. The editor turned him into "Ernest Lemaire", a researcher headed for the Breslau Berlitz school.

Using Doisy's papers and plans, Martin managed to get there. In doing so, he negotiated more than 600 miles to enter the very heart of Nazi domination.

Two hours outside Breslau, Martin found and entered the ghetto of Sosnowiec in Poland. Here, he heard his first stories of the camps. But the ghetto's conditions seemed so awful–it was on the verge of liquidation–that he was unsure what to believe. Were these stories true, or were they rumors fueled by fear? Looking around, however, he realized he saw neither children nor elders. So, as discreetly as possible, he kept searching. Within six kilometers, he discovered Katowice. The conquered city was a hub of labor camps, and one of them was attached to Auschwitz. Another one housed a French STO unit, whose men toiled with workers from the death camp. Cautiously befriending two of the STO men, Victor Martin learned everything they knew.

The slight, bespectacled professor saw Germany as the home of Kant, Goethe and Heisenberg. He sat speechless as the Frenchmen told him, "Don't try finding out what's become of your women and children. You won't see them. The Germans have ovens, huge crematoria that run day and night. When the wind blows towards us, we can smell bodies burning. How they kill these poor people we don't know; it's a mystery. But don't ask anyone anything. Everybody here knows… and everyone keeps their mouth shut."

Martin departed quickly, but was not fast enough. Before he made it out of Breslau, he was arrested. But, over two days of torture, he maintained his story. Thanks to this, he was spared and made a "translator" in one of the camps. Martin leveraged this status to his advantage and, with help from other prisoners, managed an escape. By hiding on trains and navigating forests, he then made it all the way back to Belgium. The minute he arrived, he typed a long report. Part of this remarkable document, which was sent to Churchill, can be seen in the show.

Under the name "Philippe", Martin continued to work for the underground. But he was rapidly discovered and imprisoned once again. He spent time in two more prisons and another camp, before succeeding at escape a second time. Against all the odds, Victor Martin survived.

Histories like these make you think twice before throwing around a word like "resistance". Yet the bravery on show here could well have remained, like so much, hidden. The exhibition has been organized by Didier Pasamonik, an expert on comics and the Holocaust. Says Pasamonik, "It was only by working on this exhibition that I came to really understood Jean Doisy's importance, not just to the resistance but in saving hundreds of children. One of whom, I should say, was my own mother."

Once Doisy played his part in the Liberation, he went back to just editing Le Journal de Spirou. Asked to hand in the record of his war work, he filled less than a single typed page. Belgium's government gave him the Croix de Guerre with palm, a medal usually reserved for bravery in battle. But, when Doisy died at age 55, most of what he had accomplished died with him.

"We still don't know the true extent of his activities," says Christelle Pissavy-Yvernault. "Even his own family never really knew." But, she adds, Doisy had a maxim by which he lived. This was a precept he once shared with Spirou's "Friends": Les titres de noblesse n'écrivent pas sur une carte de visite.

"Noble standards aren't meant as business cards."

Spirou dans la tourmente de la Shoah runs until August 30, 2023, at the Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris; entry is free of charge. There is also an online bibliography. The excellent catalogue is available at the Memorial's bookstore. So is Christelle and Bertrand Pissavy-Yvernault's La veritable histoire de Spirou 1937-1955 ("The Real History of Spirou 1937-1955"). Three of Émile Bravo's five Spirou books discussed in this article have appeared in English versions from Europe Comics: Journal d'un ingénu, under the title "The Diary of a Naïve Young Man"; and the first two volumes of L'Espoir malgré tout, under the title "Hope Against All Odds".