Was Belgian Andre Franquin (1924-1997) comics' greatest draftsman? One colleague who certainly thought so was Hergé. "Franquin", he declared, "is a great artist. Next to him, I'm only a mediocre pen-pusher." Fantagraphics' Kim Thompson agreed with Tintin's creator. "In terms of ultra-classic greatness," he once wrote me, "Hergé has that abstract line but Franquin has something else. He created the most complete, the most alive, the most absolute cartooniness in comics history."

A current Paris retrospective, Gaston, shares their views. It also honours a landmark birthday – the sixtieth year of Gaston Lagaffe, Franquin's most well-known character. Gaston, whose last name means "the blunder", is an dedicated idler in jeans and espadrilles. While hardly the first antihero of European comics, Gaston was one of their first post-adolescents. Franquin made him into a prototype of subversion.

Over three decades the artist honed Gaston's interests, showing him to be an inventor, a music fan, a DIY fanatic and an amateur chef. But, if his character exudes a Sixties effervescence it also has the era's disillusions. As Renaud Defiebre-Muller notes in the show, "Gaston pits personal autonomy against social control: against manners, against respect, against everyday decorum". Elevated to stardom by Franquin's graphic brilliance, this rebellion-by-default changed the rules of the bande dessinée.

Yet, at the start, Gaston was just an in-joke. Franquin and his editor, Yvan Delporte, had envisioned not a strip but a running gag. Their youth weekly Spirou was a Catholic children's journal which, like its competitor Tintin, stuck to Boy Scout values. Spirou, a red-clad bellboy, wasn't even its featured star. That role belonged to a daring insurance adjuster, Jean Valhardi.

The magazine published both a Belgian and a French edition so, between them, advertising volumes differed. The pagination problems were solved by using a centerfold but unexpected gaps still cropped up. Franquin proposed filling these with a character, "a BD hero too stupid to fit the mold". From the start, his concept was a swipe at the magazine's rectitude.

In Yvan Delporte, he found a receptive ear. Publisher Charles Dupuis had hired Delporte to make Spirou funnier. A comics scenariste with a beard the size of a copse, the editor was a character. He loved jazz, ran a private club and read comics in English. It's still funny to think about some of his initiatives, like a "spring issue" with violet-scented ink which caused the whole print works to vomit. Franquin's pitch for a house "blunderer" tickled Delporte's fancy. He threw himself into it, even naming the character after a shambolic pal.[1]

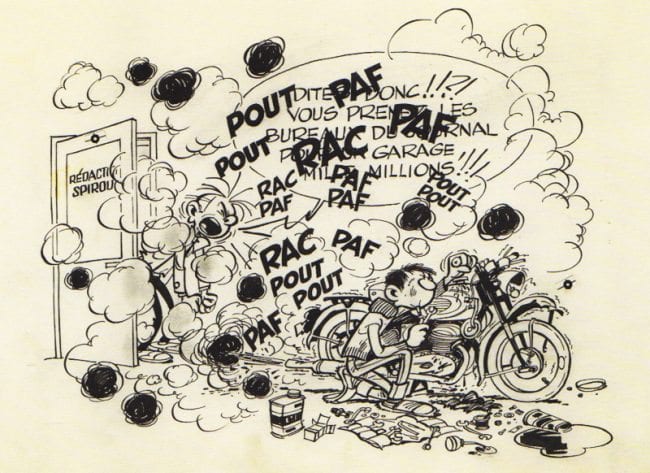

On 28 February 1957, Gaston appeared with no explanation; he was simply shown opening the door to Spirou. From then on, every week, he appeared to instigate problems. A page might be obscured when Gaston poked his face in the camera or an article lost under ink he had spilled. When an irate Spirou eventually tried to question him, a dialogue worthy of Samuel Beckett ensued. Why was Gaston in the office? Who had actually hired him? The character shrugged; he didn't know, couldn't recall and didn't care. Once in place, Gaston never left.

If the concept behind Gaston Lagaffe was simple, his actual character constituted an aberration. In that era, kiddie mags starred exemplary heroes like cowboys, aviators and private eyes. Each of them had a "job" which could further improving narratives. Despite his hopeless behavior, Lagaffe likes people. But, from the start, he was indifferent to all the problems he caused them.

At the moment he got the idea for Gaston, Franquin was overworked. Over a decade, as well as the magazine's cover, he had been producing Spirou and Fantasio weekly. Now he was starting a supplement called Spirou Poche and had just become a first-time father. If that wasn't enough, there was more one thing. Franquin also worked for the competition, Le Journal de Tintin.

This was a situation just as odd as it sounds. In 1955, miffed by a contract, Franquin had stormed over to his rivals. Once "at" Tintin, he created a new strip called Modeste and Pompon and agreed a five-year contract. Back at Spirou, the boss Charles Dupuis panicked. It took him ten days of pleading and conceding to win back his star. When Franquin returned, he was still stuck with Modeste and Pompon. Deliverance only arrived as it often would for him – via close friends who pitched in to help.

With stories from René Goscinny, Greg, Roba and Peyo (not to mention those of his own mother-in-law), Franquin added Modeste and Pompon to his weekly regimen. If it's seen as a bit of a relic today, the strip still personifies what was a heady moment. Its slick, hyperactive graphics – later dubbed le style atome – were an aesthetic powered by Franquin's love of design.

With the exception of one book (Augustin David's 2014 Franquin et le design), there's not a lot about the artist's crush on mid-century style. Yet it informs the whole of his graphic universe. From Spirou and Fantasio's pad to the Spirou "office" in Gaston, Franquin is always precise about décor. His armchairs, sofas and lights comprise exact homages to names such as the Eames brothers, Pierre Paulin and Eero Aarnio. They were of course reflections of Franquin's own taste and home. But, in Modeste and Pompon, the style atome marks something else. It stands as a groundbreaking generation's final nod to America.

Franquin had joined Spirou just after the Liberation. The job followed his brief stint as an animator, at a company shuttered when its owner was tried for collaboration. The change to Spirou brought the 22 year-old a lifelong mentor in the person of artist Joseph "Jijé" Gillain. Also a serious painter and a father of three, Jijé was easy-going yet enormously energetic. Working with Spirou's then-editor, the communist Jean Doisy, he fused his post-War hires into a singular team. Together, they built what became the "Marcinelle school" of comics.

This was a term defined partly in opposition – to the qualities upheld in Tintin by Studio Hergé. While that team stylized reality, Spirou artists spent their youthful energies milking it. Laughter was their chief priority and every path they took to it (slapstick, word games, big noses and funny animals) exuded breeziness and a contemporary air.

At the root of their success was a talented trio: Morris, Franquin and the nineteen year-old "Will" Maltaite. Initially, Gillain lodged and coached all three artists in his home. For Franquin, the only child of older Catholic parents, that arrangement filled "a desperate need to laugh". He valued it for the whole of his life and it spurred an introvert to explore the joys of collective industry.

In 1948, when Jijé went to America, both Franquin and Morris tagged along for the ride. During their trip, incredibly, Franquin kept up his weekly work for Spirou. Within five years, at the age of 27, he was a pillar at the busy publication. Thanks to his refinements, redirections and additions, Spirou's character got a much-needed update. What had once been bland adventures now received complex plots, offbeat geographies and an array of fanciful characters. (Franquin also added outlandish animals, from dinosaurs to the invented, monkey-like "Marsupilami").

When Jijé decided to linger in America, Franquin also inherited his role at the journal. As well as handling much of the magazine's most critical work, he helped recruit and integrate new artists. One of these, Jidéhem,[2] became his assistant. From 1957 through 1968, he would – fully co-credited – create much of Gaston, working off Franquin's sketches.

In Spirou and Fantasio, Franquin resuscitated family-friendly values from before the War. But, with Gaston, he exploded them. The key to both accomplishments was Franquin's way of seeing. Not only did he come at storytelling from offbeat angles; the graphic skills with which he managed it were astonishing. In a golden age famous for its many celebrities – Hergé and Macherot, E.P. Jacobs and Tillieux – André Franquin was an undisputed star.

One bit of film in the exhibit demonstrates why. It comes from a French television show, Tac au Tac, which was broadcast from 1969 to 1975. Tac au Tac filmed live, improvised cartooning duels. The Beaubourg clip features Franquin, Morris, Peyo and Roba. While music plays, these four artists silently extemporise: taking turns to create a wordless, communal cadavre exquis. Everyone is quick and funny and every addition beautifully drawn.

Franquin starts it off with a terrified, scrambling rat. Then, everyone chips in: a cat giving chase, a cop madly cycling, a tax collector, a gangster, a cowboy, an angry wife, etc. But, where others use comic tropes, Franquin's additions are always unexpected. When Peyo inserts a chicken in the chase, Morris follows with a cook waving a cleaver. Without a beat, Franquin adds a sweaty fat man running desperately. He's just been decapitated and cradles his head in an arm.

There's always a crowd around this film -- watching Franquin at his work is really mesmerizing. The artist, who crams his frames so full of detail you lose your bearings, is a virtuoso when it comes to motion. No one ever rendered it with more advanced or effortless physics. Franquin's world just won't wait, won't sit still and never listens. His characters keep ahead because they keep on going.

There's another bit of film towards the end of the show. Made in 1994, it features famous cartoonists talking about how Franquin is different. Says Charles Berberian, "Franquin is a great draftsman but he is much, much more. He's a guy who can capture all the anguish of his character by completely integrating it into the action." Morris, by then a global star from his Lucky Luke, agrees. "He was always the revolutionary. All of us make bandes dessinées. But Franquin, he's doing something else entirely."

It's a special position the artist holds even today. Marcel Gotlib, who passed away last December, was once asked why no-one has a bad word for Franquin. Gotlib shot back, "A bad word about what? Franquin's life? His work? There's nothing to reproach! …Across the whole profession, it's a total consensus: Franquin is the greatest. In terms of the bande dessinée, in terms of drawing, in terms of ideas."

In 1962, Franquin had a depressive crisis which was an omen of difficulties to come. In the midst of a story that was already running, he dropped Spirou and Fantasio for more than year. But he continued to work on Gaston. "I think in life," he said, "there comes an important moment. One when you discover that none of this is a game. That it's something serious, something where nothing is free, where pleasures are rare and finding satisfaction is difficult. It's that moment Gaston always helps postpone."

But even Gaston couldn't postpone the turbulent '60s. The riots and strikes that traumatised France in 1968 brought profound changes to all of Francophone culture. Franquin's was a generation that fell in love with American culture and worshiped postwar design for its optimism. Suddenly they were drowning ina scorn for consumerism.

In Franquin's case, these critiques were just the tip of an iceberg. Always a serious pacifist who opposed the death penalty, he became more and more disturbed by the state of the world. In Gaston, he mocked hunters, cops, generals – even those model Messerschmitts Spirou sold in the small ads. But his humor grew more and more corrosive.

In 1974, Angouleme held its founding festival. It awarded Franquin awarded the Grand Prize for lifetime achievement. But that comics world he had once shaken up was different now. It had produced names like Marcel Gottlieb (Gotlib), Philippe Druillet, Nikita Mandryka, Claire Bretécher and Moebius. All through the '60s and '70s, publishing and art were changed by new publications: Pilote, Hara-Kiri, L'Echo de savannes, Métal hurlant, Fluide Glaciale, Charlie Hebdo. The real action had moved to France – and it catered not to kids but adults. In sharp contrast, Spirou still had its "religious counselor".

Despite his growing sense of isolation, Franquin stayed with Dupuis. He turned down several offers, including one from Charlie Hebdo. Then, in 1975, he suffered a heart attack.

Although it shook him profoundly, Franquin didn't fall behind. In 1977, he and Yvan Delporte took another new idea to Charles Dupuis. It was a "pirate" publication, one that would appear inside Spirou every week. Delporte would edit and Franquin would manage the art. But they had one condition: total editorial freedom. Somewhat surprisingly, Dupuis agreed. He gave the pair an office for their project, "Le Trombone Illustré".

The Trombone roster mixed old friends like Peyo and Jijé with new pioneers such as Jacques Tardi, Enki Bilal and Claire Bretécher. Printed on paper slightly bigger than that of Spirou, what was meant as a centerfold risked dwarfing its host. This soon led to tensions back at the Spirou office. According to Franquin, "We were viciously attacked. Most of the editors really hated us." Not only were his colleagues furious with their star; many disagreed with the Trombone's brand of humor.

One of their main targets was a strip called Idées noires ("Dark Thoughts"). This, along with the supplement's covers, was Franquin's contribution. It was a series of one-page gags whose humor was utterly dark, concentrating on death, disasters and despair.

Over the years of drawing Gaston, Franquin had perfected his style. By '77 he commanded it with a highly cinematic control. But nothing had prepared either the staff or his fans for Idées noires. It looked like, in his own words, "Gaston plunged into soot". Everything in its drawings was creepily alive; even the outbursts and onomatopoeias writhed. Its landscape was baroque – yet chilling in its prevailing black and furious clouds of crosshatching.

Aside from monsters and aliens, Idées noires has two kinds of protagonist: humans who suffer and humans who relish inflicting hurt. Their figures are either utterly dark or a stark, trembling white. All are feeling their way in a universe deprived of light.

Le Trombone illustré lasted less than a year. But when the exasperated Dupuis finally ended it, Marcel Gottlieb rescued Idées noires. Gotlib gave them a home at Fluide glaciale, the all-adult comics journal he co-founded. There, until 1983, Franquin continued the strip. If he had only drawn Gaston, Franquin would be a legend. But his Ideés noires are a spookily prescient landmark. These grim gags are part Goya, part Edward Gorey. But there's no disputing the fact they remain almost shockingly relevant.

Would the strip have been born without Franquin's personal gloom? The artist himself claimed that Ideés noires was just a progression, the logical development of his earlier work. He liked to cite a Spirou sequence from 1966, in which his villain ruins a fingernail while torturing Fantasio. The higher ups, he told a fanzine in 1988, went ballistic over that. "Clearly, I had touched a nerve and that amazed me. I think that stayed in my head and Ideés noires developed from it."

But the graphics were something he had always wanted to try. "There was one Saturday Evening Post I had seen as a kid which had a strip done entirely with black silhouettes. I always wanted to use that for some sort of dark comedy. Maybe it's all gallows humor, but it's humor nevertheless." Frank knew his new look was unnervingly strong. In 1977, he used it on a poster for Amnesty International.

Mostly stark black against a bright scarlet, this appears at the very end of the show. It's a vivid and harrowing piece in which Gaston fantasizes scenes of his own torture. Says Xavier Zeeger, who worked for Amnesty at the time, "Many people were surprised by the strength of feeling in that but it shows how bleak Franquin's vision had gotten."

Fluid glaciale has just re-issued Idées noires. To mark the event, they've also published a "Golden Edition" replete with extras and graphic homages. Yet Franquin's own work that still seems by far most modern.

Editor Gerard Viry-Babel isn't surprised. "When these strips were first published back in 1977, Franquin couldn't have known that forty years on they would still be newsworthy."

"But it's exactly like Gotlib wrote when he first published them, 'From his very first dark thought, it always seemed Franquin was saying, 'Watch out; this is no longer any laughing matter..."

- The exposition Gaston, Au-delà de Lagaffe ("Gaston, beyond the blunder") runs through 10 April 2017 at the Centre Georges Pompidou in the Bibliothèque publique d’information Gallery. Admission is free.

- Il était une fois Idées noires ("Once there were Dark Thoughts"), the commemorative volume, is out now, published by Fluide Glaciale.

[1] Bohemian poet and painter Gaston Mostraet

[2] "As with 'Hergé', 'Jidéhem' stands for the French pronunciation of the artist's initials: 'J.D.M'. They belong to Jean de Maesmeker. Franquin named his Gaston character "Aimé De Mesmaeker", a boss eternally after contracts, after his colleague's father.