What, you thought I’d forgot the reading order for Marvel’s Fall 1989 crossover spectacular Acts of Vengeance? As if.

What, you thought I’d forgot the reading order for Marvel’s Fall 1989 crossover spectacular Acts of Vengeance? As if.

Also, did you know there are many pretty girls in Australia? I think about that a lot. There are many worse things to think about. (It’ll come up later.)

So, Wolverine #17 hit newsstand in August of 1989. Weird time for superhero comics – in hindsight the first part of a rollercoaster that took a while to get off the ground. (The '90s were the rest of the rollercoaster, in case you weren’t sure about the metaphor.) The metaphor in this instance works as long as we both know that by rollercoaster I am referring to one of the rickety wooden ones that looks like the last decision you will ever make. The tulips were just beginning to poke their heads up from the soil during the early months of the first Bush Administration, in other words.

Now, let’s be frank, I didn’t like Wolverine #17 when it came out. Why? I was a kid and I didn’t know my ass from a hole in the wall, for one. That’s what I want to talk about today. I read these comics twenty-nine years ago. It’s my birthday in a couple weeks – Not a milestone yet but inching ever closer to a big one in the next couple years.

I’m also inching closer to an end for what I’m doing here. Not this column, hopefully, but the specific project of this first year, a set of pieces written in a reflective mood, big on first-person pronouns and belly-button lint. The second year will be completely different. I get restless if I do the same thing for too long, I learned that from teaching.

This style has come in handy, however. You see, I underwent a change recently. It doesn’t really matter for the present purposes what that change was – we all change, after all, the experience of change is what’s universal. (Even if my change was a bit more drastic than most.) We’re all changing just by being alive and breathing the same blessed atmosphere. Not a novel observation but nonetheless a true one.

So, first, let me just say what this isn’t, which would be a hatchet job committed against seven innocent Wolverine comic books from the days of George H. W. Bush. I wasn’t looking forward to rereading these because, as I said, I remembered disliking the arc at the time. It seemed interminable when read in pieces over half-a-year. In hindsight I just didn’t care for this run because I didn’t know what I was looking at. I appreciate these comics now, and I mean that with complete sincerity. When I was just a kid I had a kid’s taste. I see now these were pretty good. Not “great,” perhaps, but I don’t think anyone involved was shooting for “great.” They’re shooting for “fun” and they hit the target square.

This also isn’t a story about these thirty-year old Wolverine comics being better in some way than comics today. That’s a pointless competition. There’s always good comics and bad, and the bitch of it all is that we don’t always get the foresight of knowing which are going to be good and which aren’t, let alone which ones are going to be worth holding on to. These seven issues of Wolverine haven’t changed at all in the intervening years but I have.

This also isn’t a story about these thirty-year old Wolverine comics being better in some way than comics today. That’s a pointless competition. There’s always good comics and bad, and the bitch of it all is that we don’t always get the foresight of knowing which are going to be good and which aren’t, let alone which ones are going to be worth holding on to. These seven issues of Wolverine haven’t changed at all in the intervening years but I have.

It’s nice to be surprised sometimes, and I confess I was when I went back to these books. At only seven issues this isn’t a particularly heralded run. Wolverine seemed an odd book for the longest time, which is a funny thing to say about a series that has always been one of the industry’s best sellers. But the fact is that Wolverine the character never needed to have his own book. There’s a reason why everyone involved dragged their feet until 1988, well after Jim Shooter left the building and into the company’s DeFalco-era surge. Claremont had done a fairly good job of fighting the inevitable pressure of franchise expansion for almost a decade, holding the line up to then at a still unbelievably parsimonious three regular X-books – Uncanny, New Mutants, and X-Factor. For most of Chris Claremont’s run Uncanny was a tightly plotted book that didn’t leave a lot of room for characters to be able to have solo adventures on the margins without a lot of juggling, so spinoffs had to be carefully planned.

Wolverine was a mysterious loner, once upon a time. It’s been a while since that was the case, however and it was probably not characterization that could have stuck for such a popular character. If you haven’t gone back to the early Claremont run of the (pre-Uncanny) X-Men anytime recently, Wolverine actually starts out as a real asshole – not a fun avuncular asshole of the Ed Asner variety, but a grating prick who gets on the nerves of every single person he meets and also probably definitely has poor attitudes towards women. That changes gradually but change it does, because he managed to avoid getting written out of the book at every point early in the run when that was a possibility. He stuck around long enough to get cuddly.

By Wolverine #17 the fix was already well in, in terms of Wolverine having slowly but steadily transforming from the annoying guy who everyone wanted to leave in outer space in X-Men #100 to a solid dude who people were very eager to trust with children. It’s a product of the fact that the character was popular that they had to sand the edges off. It was slowly revealed due to the magic of retroactive continuity that he had been bouncing around the background of the Marvel Universe for years, a Zelig in yellow spandex whose past eventually included significant acquaintances with Sabretooth, Captain America, the Black Widow, Bucky, Peter Parker’s parents (I only wish I was joking about the last bit) . . . he was a popular guy.

But every revelation about a secret past adventure took a little bit of the mystery away, and every new team-up where Wolverine met and befriended another hero (to battle the real-world problem of sales attrition, ‘natch!) only succeeded in making Wolverine more approachable. It's hard to be intimidated in quite the same way by the loose cannon loner with a bad attitude when he also just happens to be pals with everyone.

(And since this is as good a place as any to mention it – when time came to pull off all the bandages in 2001 and reveal the honest-to-God true origin of Wolverine just precisely as his creators intended all along, it turned out that Wolverine’s real name was not actually Logan but James Howlett. Wolverines to the best of my knowledge do not howl, and it always seemed to me like they were trying to give him a cool animal-redolent name without realizing his namesake creature doesn’t howl, but rather makes an unpleasant hiss-growl combo. I realize it is seventeen years too late to file a formal complaint but Bill Jemas stopped taking my calls on the matter a long time ago.)

Anyway . . . did you know there are many pretty girls in Australia?

I mention that partly because late '80s were the time when the X-Men were spending most of their time hanging out in the Australian Outback in an abandoned ghost town that just happened to be a secret hi-tech compound previously occupied by evil cyborgs. I mean, it was the '80s, stuff like that happened more often than you’d think. This was, incidentally, a bizarre time to get into the X-Men. There were a good few years there, following the Fall of the Mutants crossover, where the X-Men’s status quo was that the entire world believed they were dead, and that meant literally every time they left the Outback the story had to invent a new reason why no one ever recognized the X-Men when they emerged from a hole in thin air dressed like the X-Men to fight evil mutants.

(“Hey, you look like the X-Men, didn’t you die in Dallas on TV? Neil Conan from NPR was there and everything.”

“Nah, but we get that all the time. It’s the hair.”)

It’s a disconnected era because the team is obviously fraying and being pulled in a number of directions – both within the stories and behind the scenes at the company. Eventually the Australian era ends after a quite depressing sequence where most of the team falls through the Siege Perilous and loses their memories, precipitating over a year of the book aimlessly wandering the map checking in on every member of the dismantled team. Perhaps Claremont had simply been writing the book for too long – I actually quite like the Australia period, even if I recognize in hindsight that it is the book, the writer, and the franchise at its most baroque.

Through it all, well, Wolverine had his own book to promote, even if it didn’t really make that much sense at the time how and why the guy was going to be able to commute to his solo adventures (from Australia, no less) when everyone on the planet had seen him die on live TV. Claremont solved the problem the best way he could figure out at the time, which was to have Wolverine put on an eye patch and cosplay Terry & the Pirates on a fictional Southeast Asian island nation called Madripoor. (Worth pointing out that NBM’s Terry & the Pirates reprint series began in 1986 and the first issue of Wolverine’s solo series shipped in 1988.) John Buscema drew much of the book’s first couple years, and he’s a good fit for Claremont’s Caniff riff even if I’ve never seen much life in the setting. Obviously a personal preference, but when I think back to Claremont’s Wolverine I remember trying to keep track of all the named characters who each had their own backstory, much of which related back to Logan being a real swell dude at some indeterminate point in the past – you know, like literally every other Wolverine story ever told.

Through it all, well, Wolverine had his own book to promote, even if it didn’t really make that much sense at the time how and why the guy was going to be able to commute to his solo adventures (from Australia, no less) when everyone on the planet had seen him die on live TV. Claremont solved the problem the best way he could figure out at the time, which was to have Wolverine put on an eye patch and cosplay Terry & the Pirates on a fictional Southeast Asian island nation called Madripoor. (Worth pointing out that NBM’s Terry & the Pirates reprint series began in 1986 and the first issue of Wolverine’s solo series shipped in 1988.) John Buscema drew much of the book’s first couple years, and he’s a good fit for Claremont’s Caniff riff even if I’ve never seen much life in the setting. Obviously a personal preference, but when I think back to Claremont’s Wolverine I remember trying to keep track of all the named characters who each had their own backstory, much of which related back to Logan being a real swell dude at some indeterminate point in the past – you know, like literally every other Wolverine story ever told.

I mean . . . what we keep circling back around as I try to settle on a way to describe these comics – ugh. Here we are, almost two thousand words in, and I haven’t even started to talk about the comics yet, like one of these days I keep meaning to tell you the circumstances of my birth but keep getting distracted thinking about having to wind the clock . . . did you know there are many pretty girls in Australia?

There’s a note somewhere in this storyline stating that it takes place before Uncanny X-Men #249, which was the issue in which the team finally disintegrated and scattered to the four winds. Wolverine was the only one of the mutants who didn’t fall through the portal and get their memories wiped, and for his troubles he was crucified in the desert and only survived thanks to the help of the sensational character find of 1989, Jubilee.

Why is that note so important? Because these seven issues – #17-23 – contain an Acts of Vengeance crossover. If you’ve forgotten, the gimmick of Acts of Vengeance was at once simple and effective: villains teamed up and traded antagonists, sending mismatched villains against unprepared heroes. (This was the storyline when Spider-Man became Captain Universe, if that helps ring the bell.) Now since everyone at the time thinks the X-Men are dead no one thinks to come after them during the crossover, but Wolverine stumbles onto another of that storyline’s villain mismatches – Sub-Mariner villain Tiger Shark trying to murder a new superhero named La Bandera, from Cuba. He helps her take care of Tiger Shark while before they continue on with the adventure.

Now. Here’s where I’m confused . . . because the actual Acts of Vengeance crossover in Uncanny X-Men came in issues #256-258. So, if you’re following at home: the events of X-Men #249-255 – which occupy a significant amount of time in-story, long enough for the X-Men to scatter and Wolverine to almost die of exposure staked to a cross in the Australian desert – and do you get what I’m getting at here? – the events of X-Men #249-255 take place entirely during the Acts of Vengeance crossover. But that doesn’t make sense! Not enough story time elapses in the rest of the crossover to justify the massive amount of time between Wolverine’s two separate Acts of Vengeance crossovers!

I thought I understood the universe! I thought I knew what was real and what mattered ... and when I was a kid I had the reading order for Acts of Vengeance worked out completely in my head, even down to which issue of Captain America took place between panels of an issue of Fantastic Four. I really can’t remember the details now because, as I was saying above, you know, I’m a Libra and that means two things: I’m indecisive as fuck and my birthday is coming up soon. And it’s been a lot of birthdays since I got to enjoy spending long afternoons sitting around the house figuring out what order to read my comic books.

The reason why this matters now? The note about where Wolverine #17-23 fits into Uncanny continuity (before issue #249, which it would absolutely have to be since the story begins at the Australian base prior to the team’s dissolution) shows up at the beginning of issue #21 of Wolverine . . . which I realized as I thought out this sequence of events, I missed at the time. I bought most of my comics off the newsstand so that happened. I didn’t care about the story to ever go back and catch up with a missing chapter.

There is a part of me that is very glad I still remember enough to get worked up about skewed the internal chronology of a thirty-year-old crossover. I still remember when it was the most important thing in the world, even if it probably isn’t anymore.

So anyway, over the course of the book’s first couple years on Wolverine you’ve got Chris Claremont and Peter David both writing for John Buscema for the first year and change of the book’s existence, and then with issue #17 the new creative team became Archie Goodwin, John Byrne, and Klaus Janson. Here’s where you do a spittake because I somehow managed to bury that lede some 2200 words into this piece . . . not that I’m counting or anything.

So anyway, over the course of the book’s first couple years on Wolverine you’ve got Chris Claremont and Peter David both writing for John Buscema for the first year and change of the book’s existence, and then with issue #17 the new creative team became Archie Goodwin, John Byrne, and Klaus Janson. Here’s where you do a spittake because I somehow managed to bury that lede some 2200 words into this piece . . . not that I’m counting or anything.

There’s a reason I’ve never written much about John Byrne. It’s not that I didn’t like Byrne and didn’t grow up reading absolutely everything of his I could find, because I did. It’s not that some of his work hasn’t aged better than others, because that’s true of anyone. I loved a lot of that the man did and disliked a fair amount as well. I’m close to it in a way that I’ve found difficult to really articulate as a critical perspective other than to say – oh yeah, I read a whole lot of his stuff when I was younger.

But I learned a lot from reading Byrne as a kid, and I think one of the most admirable things about his work even given his somewhat fraught status with his contemporaries (I mean, Claremont-David-Byrne is a cursed progression by any measure on any book) is that he was straightforward about his influences in a way that encouraged readers to learn more, both to understand what he revered and aped as well as what he dismissed and overlooked – at least that was the effect on me. He was an artist whose style even then in 1989 had changed a great over the course of his tenure in the industry, in ways that I could trace and understand even as a kid.

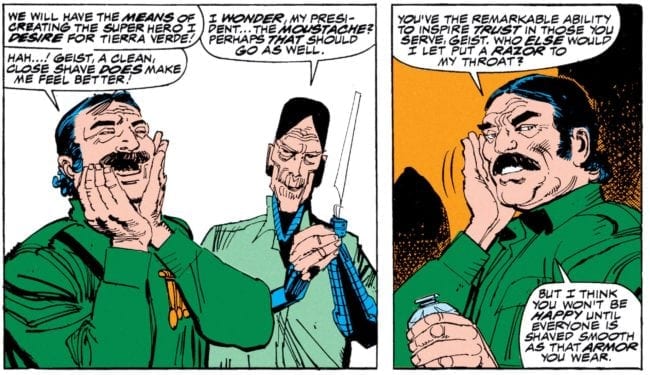

Even as I liked pretty much everything else of his that I could get my hands on at the time, however, I didn’t like this run on Wolverine. He didn’t write it, for one, and he didn’t ink it, for another, and at the time Byrne was doing some very nice looking full-ink work, first on his Avengers West Coast and She-Hulk, then on his Namor (still to this day the only time I’ve ever cared about that character). This story, however, isn’t that kind of Byrne book. Goodwin is writing and while he picks up on Claremont’s Madripoor status quo he also takes the first opportunity to send Wolverine on a boat trip halfway across the world, from Southeast Asia to Central America hunting a Nazi mad scientist who kidnapped his frequent sparring partner Roughouse. It’s very loose, purposefully, in the way that books used to be when arcs were less formally structured and more accretions of subplots that formed and dissipated in the natural course of events and at a more organic pace.

As I mentioned above there’s an Acts of Vengeance crossover a couple of issues in which introduces La Bandera, a mutant waging a war against Central American drug gangs with the ability to inspire others. (I liked the character and wondered what had become of her – turns out she died in a late issue of Gruenwald’s Captain America, a shame since she’s a fine character who seemed like she had a great deal of potential. Ah well, not like Gruenwald ever had any previous examples to learn from in terms of the hazards of killing underutilized characters for little long-term gain or anything.) The ropy plotting works because it keeps the character moving from one environment to another, with a new goon or monster to fight every ten pages or so. It hums right along.

Wolverine was never my favorite character because the milieu of his solo stories wasn’t that interesting to me. I’ve never made any secret of my preference for sci-fi and fantasy over crime and war stories, when it comes to genre fiction. A lot of Wolverine stories (this one no exception) tend to focus on Wolverine fighting a lot of guys in military uniforms or cheap suits with guns. And that’s fine but it wasn’t my favorite when I was a kid, still not my absolute favorite today. Comics used to be a lot cheaper and it was easier in that ecosystem to justify spending $1.50 for a character you only sort of liked but was perfectly readable from a decent creative team.

Now, I haven’t mentioned Janson . . . and honestly, at the time these books were released that would have been a big turn-off. I’ve changed significantly and learned a lot in the ensuing years, in that I know better than to talk in public about disliking Klaus Janson. I kid, slightly. Byrne turns in loose pencils – because honestly I can think of few more useless things you could spend your time doing than turning in tight pencils to Klaus Janson – and Janson makes them into his own, as he usually does. There are plenty of striking images throughout the book, places where Janson really pulls out all the stops . . . and then there are passages where he obscures some of Byrne’s basic anatomy with sloppy linework.

Now, I haven’t mentioned Janson . . . and honestly, at the time these books were released that would have been a big turn-off. I’ve changed significantly and learned a lot in the ensuing years, in that I know better than to talk in public about disliking Klaus Janson. I kid, slightly. Byrne turns in loose pencils – because honestly I can think of few more useless things you could spend your time doing than turning in tight pencils to Klaus Janson – and Janson makes them into his own, as he usually does. There are plenty of striking images throughout the book, places where Janson really pulls out all the stops . . . and then there are passages where he obscures some of Byrne’s basic anatomy with sloppy linework.

There are some close-ups and action sequences that look like they could have come directly out of the pages of Miller’s Daredevil, and it says a great deal about why those comics read the way they do that the same inker can make John Byrne read like Frank Miller. Janson takes the driver’s seat in every collaboration, and I’m not always a fan of that approach. It works with some artists more than others. There are passages throughout, primarily action sequences, where the layouts and the inks get out of each other’s way. But there are just as many sequences where the combination of Byrne’s staging and Janson’s embellishment don’t work quite as well. Janson is a high risk/high reward collaborator, and the problem is that for me the risk and reward usually show up side-by-side.

But I was a kid, y’know, I knew who Byrne was but I didn’t like the inking, and I sure didn’t have any historical context for why a random comic book created by Goodwin, Byrne, and Janson was worth getting het up for. These are very casual comics, yes, but they’re casual in the way that you get when you have three experienced creators basically vamping out a Wolverine road movie where he chases a Nazi cyborg to South America and ends up fighting a monster made of evil cocaine.

I’m not joking about that, see, it just so happened that the Celestials did some wacky bullshit or other back in the primordial days of Earth that resulted in a certain hillside in Central America being infested with weird cosmic power of the kind that grows magic cocaine that turns into raging super monsters who rant about their vendetta against cosmic gods from before the dawn of time. It’s one of those kinds of stories. Faulkneresque, one might even say.

You know why I liked these comics so much, in a way I really couldn’t appreciate when I was a kid? There’s no euphemism here. I think a the time, if I had to guess, I may have thought this run was vaguely crass and cynical for it at the time. I think the tone the book was going for, pitched for just a slightly older clientele than the average Marvel line by a year or two (a small bit of freedom accorded Baxter paper books at both publishers at the time, even ones like Wolverine that had newsstand distribution) was more grindhouse and early Schwarzenegger. Now the tone makes more sense.

When I was coming up in the world, if you didn’t like Wolverine you were kind of fucked. It was grating at the time because, as I said, I didn’t hate the guy but he really wasn’t my favorite. He seemed to me at the time to be a symbol not simply of masculinity but of masculinity as fetishized by adolescent boys – mysterious, embittered, violent. To the person I was at the time masculinity was scary, and I couldn’t read past the obvious and downright creepy wish fulfillment of older kids and teenagers aspiring to be, well, kind of a creep.

When I was coming up in the world, if you didn’t like Wolverine you were kind of fucked. It was grating at the time because, as I said, I didn’t hate the guy but he really wasn’t my favorite. He seemed to me at the time to be a symbol not simply of masculinity but of masculinity as fetishized by adolescent boys – mysterious, embittered, violent. To the person I was at the time masculinity was scary, and I couldn’t read past the obvious and downright creepy wish fulfillment of older kids and teenagers aspiring to be, well, kind of a creep.

Remember how, before Wolverine became the stoic samurai teacher, he was always leering and smiling when he dove into piles of goons prior to skewering them? I never cared for the character when I was a younger because he was ubiquitous and popular seemingly just for being a dick.

But, you know how it is. We get older.

I like Wolverine better now than I did when I was a kid, funny enough. I grew up, obviously, but so did Wolverine, which happens when people refuse to let go of what they liked in childhood and insist on wanting the sagas to grow older with them. People had to keep making Wolverine comics, so people had to keep finding stories to tell with the guy. A few of them have even been pretty decent.

Wolverine never went anywhere, and next thing you know he was in the movies, and suddenly everyone on the planet knew what “SNIKT” sounded like, and here we are still talking about a character created by Len Wein alongside Roy Thomas and John Romita, Sr. as a sparring partner for the Hulk in 1974. Chris Claremont didn’t create Wolverine but he built Wolverine up from very little, and the reason he stuck around in the first place is that Byrne took a shine to the little Canadian dude. Barry Windsor-Smith came along the year after these stories were printed and redefined the character in Weapon X. It took a village.

I appreciate Wolverine more now because I see that underneath the layers of violence was a character who was slowly but surely being defined by successive creators as in direct opposition to portrayals of more toxic forms of masculinity in the media. If you know one thing about Wolverine, after all, it’s that he’s constantly fighting to keep from losing himself to the savagery of his berserker rages. He suffers from the lifelong after-affects of trauma, and specifically trauma stemming from having been a pawn of the military-industrial complex during the Cold War. Wolverine fights a lot but something I notice a lot more now is just how much of these older stories Wolverine spends fighting with himself – I respect now in a way I couldn’t when I was a kid that Wolverine is a character defined by restraint and self-improvement.

Maybe that sounds corny? I dunno. Some of that characterization, as with Weapon X, was still to come as of the time of these stories, but the framework was well in place: Wolverine’s a good guy who is still nevertheless kind of fucked up. He doesn’t parachute into Central America to play white savior or Avenger, he goes on a quest to save an acquaintance and ends up helping some people who help him just as much. He doesn’t try to solve the real-world problems of the drug trade with Adamantium claws and his usefulness to the story towards the end comes in fighting the cosmic cocaine beast. He helps, but it’s not his country. (If you so desired you could probably quibble over the portrayal of the indigenous peoples of Tierra Verde who appear to have been traced directly from the same National Geographics that every other artist used to reference South American indigenous peoples from 1955-1990, but they’re only in the book for a handful of pages.)

One of the reasons I’ve been writing these columns the way I’ve been writing them is that I’ve wanted to trace with absolute scrupulous honesty my thought processes as I learned again the hard work of writing about comic books. I sincerely doubt sometimes if I’ve ever been very good at it . . . not because I don’t try but because it’s devilishly hard. There’s nothing else I’ve done as long or as consistently, for the entirety of my adult life . . . it was strange, after all those aforementioned changes, to look at what was left in my life and realize that writing about comic books still meant an incredible amount to me. I haven’t really taken anything else as seriously, but even then I know I haven’t taken it as seriously as I could have.

Three decades is a long time. I appreciate Wolverine now because he’s a guy with a lot of fucked up shit in his past who sometimes struggles merely to keep the lid on his extremely violent temper, and heh, funny enough about that . . . even after wrestling for years with gender, mental illness, poverty, the bottom line with me is always still a self-destructive streak half a mile wide. Wrath and pride. A temper than requires constant maintenance. Decades worth of resentment and self-hatred and feelings of inadequacy and jealousy, a lifetime’s worth of mental bile and puss that feels sometimes like it can never be drained . . . regret. It’s hard not to look back at empty years and not see missed opportunities and mistakes. Change doesn’t wipe the ledger unless you do the hard work of erasing the scores by hand.

And who’s fault is any of that? Wolverine? Nah, he’s just struggling along like the rest of us.

I avoided Byrne as a topic for years (though not completely) partly because for a long time his fans had a, shall we say, less than optimal reputation for argument. Now in 2018, of course, the idea of getting into a tiff with a few people on a message board seems positively quaint. There are worse fates, worse hells emptied and worse devils loosed on the world in recent days. Perhaps I have been a coward. But if so I am a coward because I’m sick of fighting, sick down to my soul.

Many Wolverine stories are centered around the idea that we are only as good as the duration since our last destructive outburst. It’s a simple notion that probably didn’t play well with me as a kid because, well, I was a kid. Then I grew up.

Many Wolverine stories are centered around the idea that we are only as good as the duration since our last destructive outburst. It’s a simple notion that probably didn’t play well with me as a kid because, well, I was a kid. Then I grew up.

Anyway . . . did you know there are many pretty girls in Australia? I think about that a lot these days. After a lifetime of regret and self-loathing and depression and insecurity and fear the best advice I have to offer anyone is this: spend as much time as you can thinking about pretty girls (or pretty boys or NBs if that’s your persuasion), don’t spend quite so much time obsessing about comic books, and take more walks.