Under cover of night, as September faded into October, bookseller Jacques Noël of Un Regard Moderne departed this life. It was not the sort of loss that cranks Le Monde into hyperbole. But outside of Noël's Left Bank bookstore, the stream of passing mourners has yet to pause. A few leave notes or flowers but most stand in silence, remembering.

That's because there is really no other bookstore – possibly no other place – like Un Regard Moderne. A literal temple to the book, it is most frequently compared to a den, a grotto or a cavern. Here the wary customer has to browse carefully, weaving in between the shaky stalactites, mountainous piles and heaving shelves of barely-balanced volumes. Noël's tiny kingdom is layered, stacked and crammed with riches: bandes dessinees, fanzines, monographs on art, graphics and literature, Beat Generation rarities, Situationist tracts, self-published everything, graphzines, underground comics, leftist lit and erotica. It's a place where Guy Debord meets Gary Panter, the Marquis de Sade sits atop Nazi Knife and William Burroughs knocks elbows with L'Association. For almost two decades, the shop has functioned thusly – both a living sculpture and a natural resource for artists, writers and thinkers.

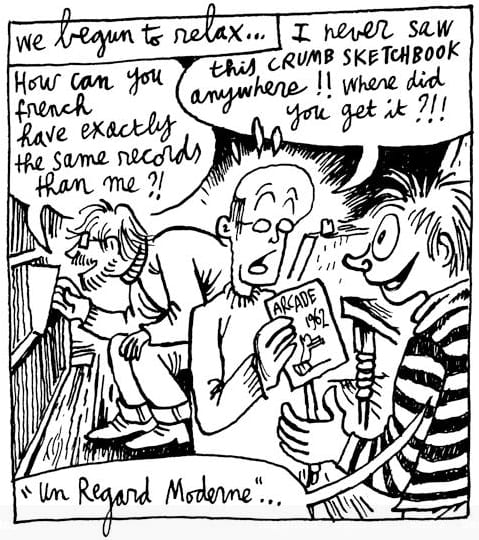

Yet a relationship with Jacques Noël was always personal. That was simply how he saw his profession. Noël viewed himself partly as an advisor and partly as a magician – a "pharmacist" charged with prescribing to (and healing) his customers. In his world, a bookseller was there to surprise his clients, not merely serving but anticipating their needs. This rule held whether the client was Chris Ware, Charles Berberian or a local who wandered in from down the street. Most of those who sought him came in search of new encounters.

The bédéiste Pierre LaPolice made a radio program on him. A "great many customers", Noël confided to him, "come in hundreds of times without buying anything… Yet they are part of my family".(1)

The shop was born out of just such a relationship. Noël had been selling books since the '60s; he became the mainstay at rue Danton's Les Yeux Fertiles. Then, at the end of the '80s, Les Yeux was sold by its owner and he made Noël's services part of the deal. The new owner, when he saw a swastika on Art Spiegelman's Maus, ordered his vendeur to take it out of the window. Noël started grousing to various longtime clients.

One of these was a publisher named Jean-Pierre Faur. Faur, it transpired, had always dreamed of owning a bookstore. But he couldn't really see himself selling the books. Still, he had a property round the corner in rue Gît-le-Coeur. A onetime driving academy, this had already known bookselling and publishing – albeit in the 1808. Faur offered it to Jacques Noël as a place of his own.

The name the new proprietor chose contained a history of its own, one that poetically encapsulated his aims. During the late '70s, Un Regard Moderne was the fanzine of punk graphics collective Bazooka. Its members Olivia Clavel, Kiki and Loulou Picasso, Romain Slocombe and Lulu Larsen had studied together at the Paris Ecole des beaux-arts. They shared an aesthetic of equal parts subversion and drama, one whose imagery was always collaged, distorted and altered. During the spring of '78, after Bazooka staged a "graphic occupation" of Libération, the newspaper started to publish Un Regard Moderne.

Despite its ephemeral nature, the publication was influential. Libé 's then editor Serge July calls its creators "the first generation to make a near-total break with the Gutenberg environment… a generation which made their eyes the basic organ around which language is organized".(2) In London, Bazooka inspired a student called Al McDowell to form his own graphics collective. Then, in 1980, he co-founded i-D magazine.

Since it opened, Noël's shop has emanated the same kind of ripples: spreading both ideas and imagery, forging unexpected ties. Those discoveries, epiphanies and relationships have crossed all all borders, including those of class, language and nationality.

When Noël took over at number 10, rue Git-le-Coeur, he also joined a very singular history. Un Regard Moderne sits halfway up a medieval street, one that looks a bit like an alley. Between the 12th and 16th centuries, its name changed numerous times. The current one, "Git-le-Coeur", is the source of numerous stories. (On a tomb, the term "ci-gît" means "here lies", thus the street's title translates into something like "here lies the heart"). Older city guides say it probably marks the assassination, in 1358, of Etienne Marcel. A prevost, reformer and defender of local artisans, Marcel is often called the first mayor of Paris.

But it's number 9, on the other side, that has become the magnet for the tourists. After 1933, over three decades, it was a boarding-house run by Monsieur and Madame Rachou. The place gained worldwide fame in Life magazine as "the Beat Hotel", a flophouse for creatives such as Chester Himes, William Burroughs and Brion Gysin. It remains a hotel today – a four-star, luxury, "destination" spot.

That contrast in character is a crucial thing about Un Regard Moderne. As writer Warren Lambert noted in one of many tributes, Jacques Noël was "a Mohican", one of a vanishing – and almost vanished – breed.(3) His insistence on face-to-face connections made him atavistic. Chez Noël, says Lambert, "Books were always a method of you and he becoming acquainted. Each time he placed one in your hands, he was thinking that yours were the right hands. That they were the ones for which this book or that review or this particular fanzine was printed… in this, he was rarely wrong". Noël believed in books as an encounter. If the act of reading was indisputably solitary, he felt, those acts of proselytizing and spreading the word must remain human.

Jacques Noël followed art and thought from around the world; visitors from everywhere could and did cross his threshold. But every one of them was entering the universe as he saw it. An initial foray into this world was often intimidating – and he knew it. “It's not easy to enter a shop that often looks like it's closed, one that wants to seem like it's closed. But, then, all of us need a step to surmount".

At 71, however, Noël had few illusions about the age in which he lived. He was frank about confessing financial difficulties. "The Internet is not the only way to make people discover things," he told Carón Kiddo back in 2012.(4) "But if something can't be found there, it doesn't exist…and that can make the battle impossible… I can't sell something which doesn't exist". In recent years, he noted, people had less to spend. Then, since the attacks, they came calling less frequently. Yet he never expected anything to be easy. As he also told Kiddo, "It's worth hanging on ten hours a day, even if only one of those hours brings pure pleasure".

His legacy is an immense one. In a post which now hangs on the closed door of his shop, artist Stéphane Blanquet sums it up with eloquence:

He was one of us, one of all of those who do, those who make images, make texts, make books, who make books out of words and out of pictures, those who make unique books, one-off books, books which burst at the seams, MAXIMAL books. Jacques Noël is a part of me, Un Regard Moderne is a part of me, a part of us, of our history, the history of those who create, of those who love those who create and of those who follow them.

Jacques Noël was himself a creation and a unique one, generous and, despite appearances, always organised; a singular creation made out of books and forged with all of us in his own particular place, his Un Regard Moderne.

Jacques Noël defended both the most obscure and the most obvious, the most advanced and those who were indefensible elsewhere.

He fought, he searched, he rooted things out, he set off on the most unknowable of detours, in order to find us treasures, to find the nuggets made out of three photocopies, the jewels still stinking of ink. Jacques Noël is part of us all and part of me.

This loss also proposes a pointed question. All of those who benefited from such largesse, such determination – what kind of world do we want? What kind of books and art? How much are we prepared to work to keep them truly human? Once or twice a week, I'll still be crossing the rue Gît-le-Coeur. There, I often saw Jacques Noël out having a smoke. With that dark-clad figure missing, I hope I can keep asking those questions.

• The Centre National du Livre's review L'INqualifiable is creating an homage to Jacques Noël. If he touched your life, or stocked your work and you wish to contribute, contact Philippe Liotard at [email protected]

- http://arteradio.com/son/12327/le_regard_moderne

-

Le graphisme punk, Liberation, 12 August 1977

- https://www.facebook.com/UnRegardModerne/?fref=ts

- http://gonzai.com/le-regard-moderne-une-librairie-sans-fard/