It’s been three days since Henriette Valium (or Mister Patrick Henley) has passed away and my Facebook feed is still completely filled with memorials and pictures in reaction to his early death at 62. I have never seen such an outpouring of emotions in my life over an artist’s death (and it continues apace as I write this obituary).

Henriette Valium, often described as Le pape de l’underground (the pope of Montreal’s underground), had been a beacon of inspiration and resilience for local comix artists for 40 years.

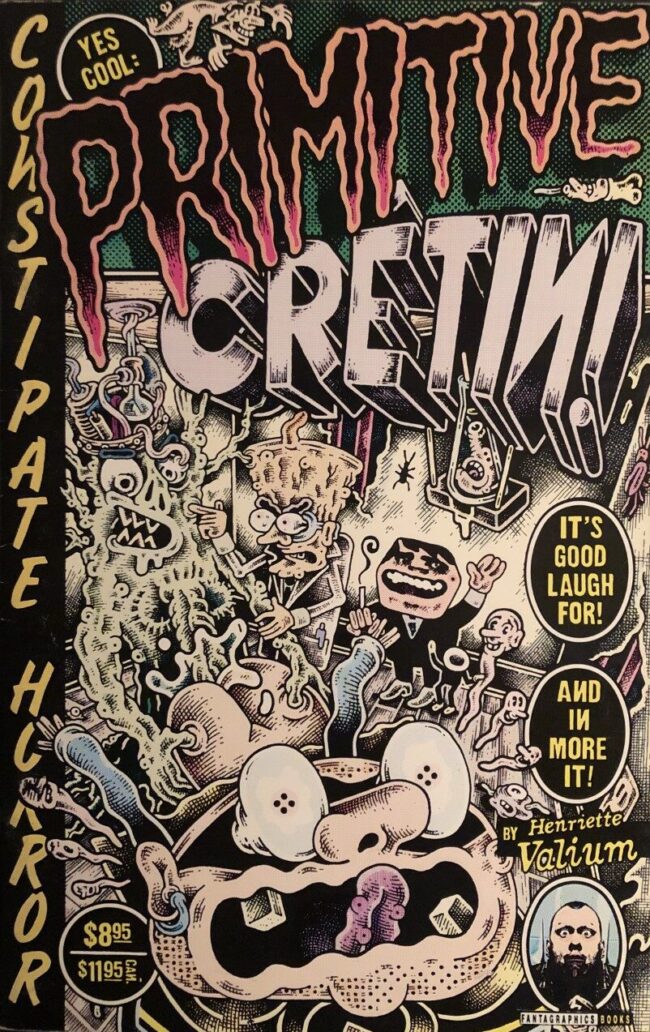

At the start of the '80s, Valium began to self-publish. First with photocopied and stapled comics (Vajorbine 14, 1981; and Iceberg, 1983), then graduating to silk-screened covers (Motel, 1986; 1000 Rectums, c’tun album Valium!, 1987) and finally, silk-screening whole books in his studio in very limited editions (Primitive Crétin!, 1993). His books were astounding works of art, outside and in. Every single line meticulously rendered, as close to perfection as one could get. Each book an artistic marvel from an artist who never counted the hours that he put into all his projects. Valium was full of rage inside and it was his saving grace. The practice of art became the salvation that kept him sane in a fucked up world. Ultimately in his later years Valium found peace and balance through creation. Imagine an artist with 40 years of non-stop art making; polishing a sharp bright mind, always creating and experimenting, always keeping himself at the top of his game. Rupert Bottenberg, music journalist and fellow artist, has aptly described Valium as the «Hieronymous Bosch of Montreal».

Thus, he would be at it all day, switching between canvasses, collages, music, videos, silk screening and comics. He could spend days, weeks or years working on a complex multi-level canvas with collaged pieces. Every single piece of art met the high level of perfection he had strived for in his constant artistic practice. For me, looking at the contemporary art scene in Quebec now, Valium is the most important artist of the last few decades. Surprisingly, if you discount his devoted fans and admirers (and there are a lot here and in many other countries), he was never able to completely break out of the underground scene like Julie Doucet did with her comics, silk screened art objects and collages.

I first met Henriette Valium in 1987 at the launch of his first collected book, 1000 Rectums. He already had the reputation of being the top underground comics artist in Montreal. Months later, I went to his office a couple of floors over the famous Montreal nightclub Les Foufounes Électriques. Valium had achieved another kind of celebrity designing and silk-screening all the posters for shows and events at Foufounes. In his office, he had a little glass display case showcasing some of his comics and silk screen works. Valium always dreamed of opening a small museum where all his art in all its various forms could be displayed. At the start of the '90s artists like Julie Doucet, Marc Bell, Richard Suicide, Caro Caron, Hélène Brosseau, Denis Lord, Simon Bossé, Rupert Bottenberg, Alexandre Lafleur, Billy Mavreas, Howard Chackowicz, Rick Trembles, Eric Braün and so many others all knew and were influenced and inspired by Valium. He was there first, he showed the way, and we all followed in his tracks.

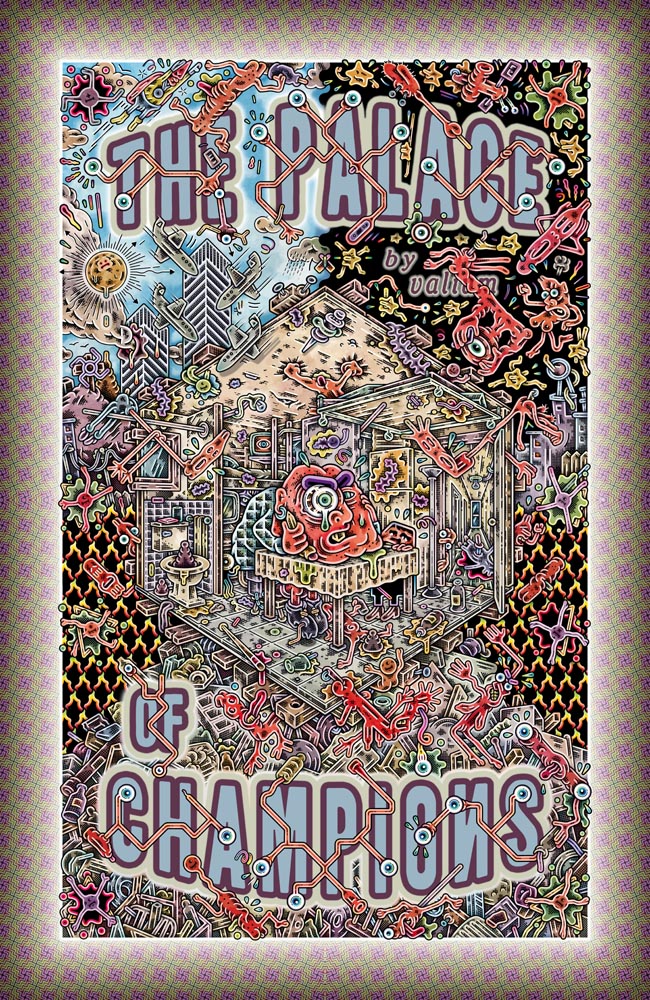

Then, in the mid-'90, a new generation of comics artists like Carlos Santos, Mathieu Massicotte Quesnel and Guim were in awe of his drawing ability and literally revered Valium as their god. The adulation by other artists did not stop with them. With recent projects like Nitnit and the Pink Lambda Mystery (self-published initially, also in hardcover from Crna Hronika) and The Palace of Champions (Conundrum Press for the English version, Moëlle Grafik for the French one), young artists were discovering Valium and were still blown away. After more than 40 years of producing an incredible body of work, the Canadian comics community seemed at last ready to embrace his art. He won the Pigskin Peters trophy at the Doug Wright Awards in 2017 for The Palace of Champions. This was followed in Quebec City in 2018 by the Prix Albert-Chartier, honoring him for his artistic contributions to the Quebec comics scene. Finally in 2020, he won the Expozine award for best comic in French (for Nitnit).

All the awards were fine and dandy except no money came with them. His lack of durable and serious recognition for his contributions to the Quebec arts scene did not allow him to live off his art. Over the years all his grant applications were rejected. He lived on welfare and eventually settled into a garage that he renovated into an incredible studio and living space.

This lack of institutional support can be attributed to the darker subject matter that he tackled, like suffering, anxiety, sex, racism and fascism (the swastika being a graphic motif that he would often use). No light subjects or abstract ideas here. Some of his images are so unsettling they would spark debates whenever they were shown. Nicolas Verstappen remarked that Valium’s art "Burned my retina more than once..."[1]

The series of collaged images called Curés malades (“Sick priests”) (published by Le Dernier Cri in France) would consist of a portrait of a Quebecois priest superimposed in collage over pornographic images. Following in the footsteps of Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Valium created an effect where at first glance, you’d only see the surface image, the portrait of the priest; but when you looked close, real close, you’d start to see underneath shocking sexual elements. There was an exhibit of these in a small gallery in Montreal. It was talked about in the press and a one of his collaged priests made the cover of the TV and weekend activities guide that was included in the Saturday edition of Le Devoir, a serious and respected newspaper in Quebec. NO ONE looked closely at the image of the priest and it was distributed across Quebec. This could have started a raging controversy; but most, who were unfamiliar with his art, took the image at face value and saw absolutely nothing!

Valium continued to explore this alley, being even more radical with his collages than the respected UK artist Linder, who also uses sexual imagery from pornographic magazines in her own collages. Gallery director Robert Poulin started to represent Valium, buying his art and paying him a monthly stipend. He had his first show at Espace Robert Poulin in 2013.

Who’s afraid of Henriette Valium?[2] To this day, a lot of people have the misconception that Valium is not for everyone, that it’s too disturbing for regular folks. I disagree. Valium’s art sparks debates, discussions, and exchanges of ideas. He is a provocateur, but his stance is justified and fits within the context of an artist challenging himself to explore the limits of his personal boundaries.

In 2009, I asked Valium to contribute to a collective publication that I was editing. He sent me collaged images taken from what looked like pornographic images of underage women. My wife was so shocked by them that we fought over whether to publish them or not. In the end, it came down to this: could I defend these images on social and artistic grounds if the book got into trouble? Yes, I could. I ended up putting aside a few images and publishing the rest. To this day, it’s still a very provocative portfolio. The negative effect of all these explicit collages is that a lot of people remember just those when they think of Valium. Valium liked to turn the spotlight on shit that people did not want to acknowledge. A powerful image that disturbs deeply is often the mark of an exceptional artist.

Earlier in his life Valium drank a lot. Like most underground artists here in Montreal, it was either booze or drugs that fueled us. More than a decade ago Valium decided to quit drinking. Sobriety made him friendlier and definitely grounded him. As Valium worked on his new graphic novel (that he did not complete) or his collaged canvases, his daily practice brought him joy and a measure of peace. To be around him in the last few years was to enjoy the company of an extremely vivacious and joyful person. His charm, his subversive humor and razor sharp wits always amazed and made us laugh. He was a character living a life less ordinary.

His passing has created a void here, an immense one. At his funeral last Thursday his ashes were laid in an empty can of silk screen paint surrounded by the last canvases he was working on. Maximum capacity was for 50 people inside. His close family filled that room while outside more than 200 artists and friends came to pay their last respects. Olivier Henley, Valium’s oldest son, is working on creating the Henriette Valium Foundation with the help of his siblings and Valium’s girlfriend, Silvia Gérome.

When Henriette Valium was alive in our comics community he was a leader that we all looked up to, a fucking relentless beacon of inspiration. The famous Montreal comix scene began with Henriette Valium. He was there at the start, and I daresay it could not have existed or thrived without him. We owe him so much.

Like Julie Doucet and Michel Rabagliati, Henriette Valium was one of our greatest ambassadors. The best we can do now is make sure that no one forgets Henriette Valium and the amazing artistic legacy that he’s left us.

Marc Tessier

September 10th, 2021

* * *

[1] As reported by Paul Gravett in his Facebook post on Valium’s passing.

[2] To paraphrase the censured poster that Robert Crumb did for Angoulême in 2000, Qui a peur de Robert Crumb?