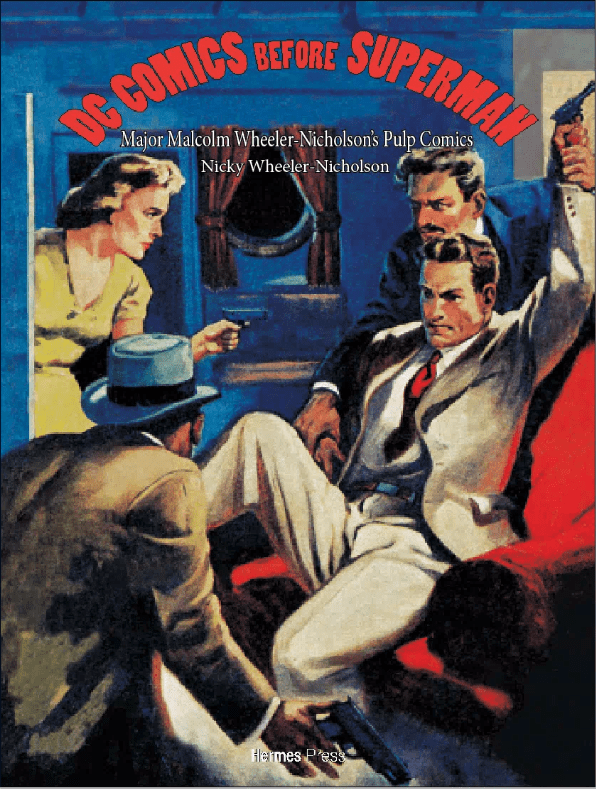

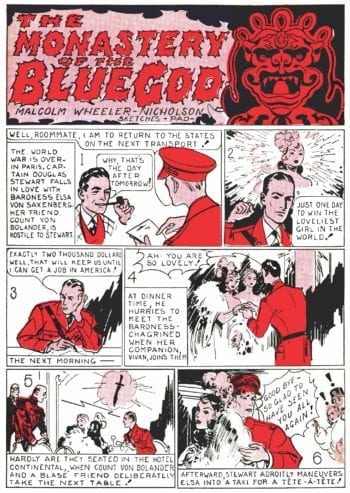

Comics (in and out of books) had been around for a very long time before anything resembling a comic book industry began to emerge in the 1930s. It is only in light of the pulp magazines that directly preceded them that these crude compendiums of flying pals, ageless priestesses, and inscrutable and vengeful enemies of the human race can even begin to make sense today. Nicky Wheeler-Nicholson's DC Comics Before Superman: Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson’s Pulp Comics provides the story of one entrepreneur who brought some innovative notions to the comic book table with a foot planted squarely in both the pulp and comic strip camps. The scope of Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson’s publishing activity lasted only a few years, but they were crucial ones for comic books, where the groundwork was laid for much that came afterward. The long-form stories reprinted in this volume are adaptations of the Major’s own pulp fiction, with collaborators ranging from action-oriented newsprint veterans like Tom Hickey and Leo O’Melia to ornate pen and ink stylists like Sven Elven and Munson Paddock (a personal favorite whose quirky cartooning became aggressively odder in ensuing years.) Sprinkled throughout are samples of embryonic work by familiar creators like Jerry Siegel, Joe Shuster and Walt Kelly who all first found national exposure in the Major’s publications. Besides the voluminous pages of never-before-reprinted cliffhangers, DC Comics Before Superman is a compelling profile of a comic book pioneer, filled with a wealth of tantalizing nuggets: Who knew that this respected military strategist and industrial paint innovator also wrote and syndicated the elusive 1926 feature, Hi-Way Henry?

Mark Newgarden: Your grandfather’s story (as well as the contents of this book) cast him as a veritable missing link between the pulp magazines and the emergent comic book industry. This was a man who wrote adventure stories for titles like Adventure magazine because he actually had adventures. Can you give us a little background on Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson prior to his writing career?

Nicky Wheeler-Nicholson: Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson attended the Manlius School, a military academy, and went into the army as a “shavetail” officer, a second lieutenant. His first assignments were on the Mexican border under the command of General Pershing. From military records it appears that he was often out on patrol with his men. In Adventure, October 1, 1927, he stated “commanded Troop K Second Cavalry Fort Bliss and Sierra Blanca, Texas, border troubles with bandits…”

In late 1915 he was finally given the assignment he had requested when he joined the army, commanding the 9th Cavalry Machine Gun Troop, a troop of African-American Buffalo Soldiers. He and his men went to the Philippines. Although fighting with the Muslim Moros had mostly ceased by mid-1913 there were outbreaks (that continue to this day). MWN was sent out from Camp Stotsenberg into Luzon with his men to map the area. In the same issue of Adventure, MWN stated, “Foreign service transferred me 9th Cavalry Philippines, commanding newly organized Machine Gun Troop broke world’s record machine gun fire, played polo, pistol expert, expert rifleman every season won Officers’ annual race Manila, selected as one of three majors in Philippine department to go with 27th infantry to Siberia.” It was during the Philippines posting that he saw firsthand the prejudice his Buffalo Soldiers suffered. The world’s record machine gun fire he mentions happened because he challenged his superior officer saying he could train his men in machine gun readiness against the colonel’s men and his men could win. Not only did they win but also broke world records embarrassing the colonel in front of the high brass. This scenario was the beginning of troubles that eventually led to the court martial.

He was transferred to military intelligence in 1917, and at one point attached as a liaison with the Japanese General Staff. He was also in China. In the Adventure article, he recounted that he “commanded 3rd Battalion, spoke French and Russian, made liaison and intelligence officer to Japanese General Staff and Russian White Forces, marched battalion to Nikolsk, to Ussuri, to Khabarovsk, Siberia on the Amur.” According to letters obtained from declassified military files during this same period, he was sent on a secret mission near the Tibetan border.

He was transferred to military intelligence in 1917, and at one point attached as a liaison with the Japanese General Staff. He was also in China. In the Adventure article, he recounted that he “commanded 3rd Battalion, spoke French and Russian, made liaison and intelligence officer to Japanese General Staff and Russian White Forces, marched battalion to Nikolsk, to Ussuri, to Khabarovsk, Siberia on the Amur.” According to letters obtained from declassified military files during this same period, he was sent on a secret mission near the Tibetan border.

His last foreign assignment took place after WW1 when he was sent to France and then Germany with the Provisional Forces. One of the interesting details from this period is a story he wrote for Adventure, January 15, 1930, “The Shadow of Ehrenbreitstein”, which I discovered in researching the declassified files. The story alludes to a plot in post-war Germany for a US-held military fort to be attacked by a rebel group of Germans. The fact that it was in the files is intriguing. All of these places figure in many of the pulp stories that he wrote and the some of the comics derived from these stories. “Blood Pearls” in the book takes place in the Philippines. MWN’s use of background details in his writing is especially notable in these tales.

The final chapter in his military career was the court martial that occurred as a result of trumped-up AWOL charges. His JAG lawyer was able to produce evidence that acquitted him. However just before the trial was to take place, he was shot in a strange incident that has the appearance of an attempted assassination. MWN had been to Washington to attempt to speak to President Harding about the charges against him and arriving at Camp Dix late at night he was unable to get into the officer’s club, so he went to his lawyer’s quarters. He could not rouse him after knocking loudly and went to a back window that he knew was unlocked. When he attempted to go in the window he was shot by an unknown person in the darkened quarters. Later it was claimed that it was a guard, but the entire situation is peculiar. The bullet entered his temple, missing his brain, missing his spine, and came out on his side. He was left bleeding on the ground for some time before help arrived. MWN was sent to Walter Reed Hospital and while there wrote a letter to Harding that was published in the New York Times. This was the fourth charge in the court martial and he was put back forty files as a result (meaning he would have to wait for forty people to be advanced in rank before him). It was basically a slap on the wrist, but with everything that had happened he determined to leave the military.

What drew him to publishing? He seemed to gravitate to comics from the outset, first as an aspiring newspaper syndicator and ultimately as a publisher. Do you have a theory as to why this prodigious pulp contributor didn’t venture into the pulp business itself (a common background for his comic book competitors)?

What drew him to publishing? He seemed to gravitate to comics from the outset, first as an aspiring newspaper syndicator and ultimately as a publisher. Do you have a theory as to why this prodigious pulp contributor didn’t venture into the pulp business itself (a common background for his comic book competitors)?

MWN’s grandfather, Christopher Wheeler, founded a newspaper after the Civil War in Jonesborough, Tennessee that is still in print. His mother was journalist at a time when women rarely had a profession. Growing up in a household where writing and journalism was part of the culture it was natural that he would be drawn to writing and publishing. Instead of going into pulp publishing, I think he was always looking for what was new, what had potential, especially something that could be of benefit to society. He felt that comics could be used to help educate and bring literature to a broader audience. MWN was also a decent artist himself. There are early drawings of his in the Manlius yearbook and he drew some of the comics for the newspaper syndicate.

Major Wheeler-Nicholson was one of the first comic book publishers to specialize in marketing original material (including his own) to young readers. Was this a reflection of his prior venture into newspaper syndication or was there perhaps a broader vision at play?

I don’t think it’s an either/or situation but more of an organic growth of an idea. There is a through line from the early newspaper syndication to the comics coupled with his experience as a writer of pulps that blossomed into a much bigger idea of original comic books. He saw the reprints of comics from newspapers that were on the newsstands and naturally as a creative person thought it would be appealing to the public to have original comics, something that stood out from everything else that was being offered thus New Fun—it’s new and it’s fun. In one of his letters to Jerry Siegel he discouraged him from putting Superman into syndication as a result of his own experiences, but felt that Siegel would do better financially if Superman should have his own comic in four colors. That’s pretty prescient, I would say. Since the Major’s terms with his artists and writers was the standard pulp terms of “First North American Serial Rights,” he assumed that they would be able to make a good deal of money from their work. As a creator himself, he followed the precept of people maintaining the rights to their work.

As Jim Steranko points out in his introduction, Wheeler-Nicholson’s heroic, larger-than-life background still left him singularly ill equipped to do battle with his business associates in the underbelly of the depression-era magazine business. How did Harry Donenfeld and Jack Liebowitz enter and exit the Major’s life — and what happened in between?

As Jim Steranko points out in his introduction, Wheeler-Nicholson’s heroic, larger-than-life background still left him singularly ill equipped to do battle with his business associates in the underbelly of the depression-era magazine business. How did Harry Donenfeld and Jack Liebowitz enter and exit the Major’s life — and what happened in between?

That question is worth at least two chapters in the biography! I’ve seen various scenarios posited about when Donenfeld and Liebowitz got into business with MWN, but I’m still not quite certain and I’ve been tracking every tiny clue of where they overlapped for almost twenty years. Most historians place it at the point where Donenfeld took over the printing of the magazines but I suspect it was earlier. The pulp publishing community in New York was not huge. People in the industry knew of one another and about one another. I think there are a number of factors that led to their connection. Just as today in New York City anyone who works in the business of construction knows they are going to be dealing with payoffs. It’s part of the cost. It seems from what we do know that a similar situation existed with distribution of magazines on newsstands. My guess is that MWN knew he would have to shell out cash payoffs as part of going into business. At the same time Harry Donenfeld was dealing with censorship that occurred as the result of the repeal of Prohibition. There was a crackdown on obscenity among other things. Between the Major’s need to stay in business and not run afoul of the system and Donenfeld’s need to legitimize his publishing or possibly launder money, their interests overlapped—exactly how and when I’m not completely sure. Once the Major partnered with Liebowitz for Detective Comics in 1937, the pair slowly coerced the Major into signing away more and more of his rights. MWN alludes to this in the bankruptcy court proceedings and if you look at the legal documents that were signed prior you can see the pattern of the intention to take his business from him. The family story is that Donenfeld and Liebowitz offered him $75,000 for the company and he could remain as creative director. He naturally refused and that’s when they lowered the boom. I have some proof of that but not enough to say it is an accurate story. It probably has elements of truth as most stories do.

Siegel and Shuster emerge as “discoveries” of Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson. How does Superman figure into the Major’s story?

Siegel and Shuster were young and inexperienced and from what I know about my grandfather (and from his communications to Jerry) he saw their potential and wanted them to succeed. He went about that by treating them with respect and encouraging their work at the same time giving diplomatic critique. That’s what a good editor and publisher does. It’s also in keeping with his management style learned in the army. He believed in leading men by encouraging everyone to do their best for the greater good.

As far as Superman, that’s a complicated part of the story. Before I ever started on this journey I heard about Superman and my grandfather as a very young child. I knew he had something to do with Superman but it wasn’t clear exactly what. As an adult I was told by my father and aunts and uncle that the Major was working on the comic of Superman and that it was stolen from him right before it was scheduled to come out. There are various versions, but everyone in the family remembers discussing Superman at the dinner table and being asked by their father what they thought about it. I have not been able to fully reconcile this story with established stories of Superman’s debut in Action.

There are holes in the established stories that don’t quite make sense and I’ve looked at those for clues. For instance, the whole slush pile story is ridiculous. There was no slush pile that the Superman story was languishing in. Jerry Siegel was attempting to get Superman published everywhere. A lot of people in the industry knew about it and most of them had turned it down, so it wasn’t a secret. Action Comics was the Major’s idea and since they were usually working 4 months ahead of the issue date, it seems probable that Superman’s potential inclusion was already being discussed by MWN with the editorial staff (including Vin Sullivan and Whitney Ellsworth.) It’s just too coincidental that the minute MWN was forced into bankruptcy the Superman story surfaced. The other aspect that I don’t think I have ever seen addressed is why was Jack Liebowitz so determined in early December of 1937 to get Siegel and Shuster on board without the Major’s knowledge and while the Major was still the owner of National and part-owner of Detective Comics (as well as involved in the day to-day operations)? Was Liebowitz communicating with other artists and writers? Why these two specifically and why at this particular time? Most people don’t think about the context of the story of Siegel and Shuster being bamboozled into giving away their rights. It’s simply taken for granted that because of Superman Liebowitz would have done that but if Superman wasn’t even on the table in December, what was the reason for pushing them to an agreement? I’m still searching for the answer to that question.

What do you see as your grandfather’s legacy?

What do you see as your grandfather’s legacy?

In 1934 Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson’s vision of original comics magazines became the foundation of the comic book industry as we know it today. He inspired and encouraged others to join in creating original comics and found working studios of artists like Chesler and later Iger and Eisner. People followed his lead. All of this occurred in the midst of the Depression in a completely new medium! Many of the people he hired and encouraged to create went on to become legendary for their innovations at the beginning of this era. The concept of the hero taken directly from the pulps with the kinds of stories taken from the pulps as well as the names of the comic magazines themselves—Action, Adventure, Detective--are directly attributable to him. He also created strong female characters and one of the first female heroes with her own series: Sandra of the Secret Service. Once you see these comics (which is often difficult due to scarcity) you have a greater appreciation for this explosion of creativity. My grandfather was a cosmopolitan, educated person who loved writing and the act of creating. He also loved the collaborative nature of publishing and seeing artists bring their ideas to completion.

What’s next for Nicky Wheeler-Nicholson?

I’m working on the full biography of the Major and writing a script based on some of the Major’s pulp stories. And I’m going back to my southern roots and finishing a novel I started several years ago.

Mark Newgarden is a cartoonist and co-author (with Paul Karasik) of the Eisner Award-winning How To Read Nancy. He teaches at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and the Parsons School of Design in Manhattan