Last time, we saw how comics with sound effects offer a strange variety of audiovisual entertainment in which the human voice mediates between the eye and ear, and how Yokoyama Yūichi’s comics foreground this like few others. At the beginning of that essay, I wrote that, given their handy size and light weight, one might further describe comics as the modern age’s first portable audiovisual entertainments, with the human voice again contributing, by making up for what printed books lack by providing a stand-in for their missing acoustic hardware.

Is Yokoyama plugged into portability as well? Clearly he is into mobile eyes and mobile ears. How about mobile devices and mobile books, and the techniques of miniaturization, content formatting, and sensorial coordination that they require? What follows is a meandering stab at an answer. It will make much more sense if you first read this essay’s prequel.

3: Mini Mega

When it comes to figures of size, Yokoyama clearly favors bigness. His earliest manga, the building narratives in New Engineering (2004), feature gigantic landworks and monumental fantasy structures. Travel (2006) promises an entire long-distance train trip. Garden (2007) features hallways that extend into infinity and giant maps that describe an entire territory in detail. After Garden, I recall Yokoyama saying he wanted to make a 1000-page book depicting war, though he never did.

In all such cases, however, Yokoyama packs bigness into smallness. His books are rarely longer than 300 pages, and often much shorter. Like any comics author, he has to work with a finite number of small panel frames – which would be a meaningless observation were there not indications that Yokoyama has been interested in this aspect of comics-making on a figurative level. For example, the endless hallway in Garden turns out to be a library filled with wordless picture catalogues, suggesting that the entire universe can be condensed, quasi-wordless comics-like, into an accumulation of printed pictures without help of the written word. The horde of photographs dropped from the air and assembled into a map in Garden suggest a similar idea: when a large set of pictures/panels is properly ordered, they can recreate, even if the individual units are small, the world in near whole. Likewise, Travel might be ambitious as a comics project, but it also harbors within it the humble desire of the armchair traveller that the world be adequately contained and enjoyed vicariously through books, screens, and other domesticated media. As encyclopedias are vast by virtue of being compact, so Yokoyama has explored monumentality, infinity, and comprehensiveness through figures and practices of miniaturization, division, and containment.

Similarly, when it comes to the things that his human figures use, Yokoyama demonstrates a penchant for objects, vehicles, and structures that are compact and portable. In the first part of Outdoors (2009), a man operates a hi-tech drone system from inside a building barely big enough to fit even him. In the second segment, the humans inhabit small cockpit dwellings with seats enough for one. And while the final segment of Outdoors features a group of three men setting up a campsite, each sets up his camp individually, using tools defined by their ability to de-miniaturize: the goo out of the tube that turns into a tarp, and the sleeping bag whose decompression Yokoyama has dramatized by depicting the rolling out laterally. What is a camp but a temporary and portable living situation? What are the dwellings in part two but house, car, and sound system folded into a single structure?

Sure, one of Yokoyama’s earliest works, “Memorial to Newton” (2002) in New Engineering, featured Étienne-Louis Boullée’s Cenotaph to Newton (see “Memorial to Newton”). But even in that case, even within the context of an homage to a famous mega-monument, the sphere and blocks are prefabricated and roll themselves onto the scene like remote control or self-automated toys. The army of men that would be needed to build the structure in reality only show up at the end, to climb on it in celebration. Working the other way, Garden spends many pages showing people manipulating shapes and objects in a ludic obstacle course. They are careless and destroy many objects and structures, ultimately causing the world to be ravished by an apocalyptic windstorm. As with playgrounds that feature shrunken mountains, dinosaurs, and castles, or toys and games that involve world war and the building and destruction of civilizations, play in Yokoyama’s work is typically conducted upon the miniaturization of the grandest, vastest, most destructive, or most sublime. If homo faber as homo ludens is a recurrent theme within Yokoyama’s work, so is the related quasi-cosmological idea that worlds are created and destroyed through naïve and child-like, divine play.

Thus, Yokoyama may look like a high modernist, pulling on the audio and visual experiments of the historical avant-garde and the bizarre structures of visionary architecture all the way back to the late eighteenth century. But the way he recodes this modernist legacy for contexts of couture style and recreational leisure emptied of any utopianism other than one of pure play marks him as an artist of the postmodernist age. His penchant for zany play upon traditional figures of the sublime encapsulates (probably unconsciously) the trajectory of core modernist tropes as they have been reinterpreted from romanticism to the present. While toying with romantic mega-monuments and sublime cosmological themes in New Engineering and Garden, Yokoyama updated the visual language of Futurism and its obsession with mechanization and vehicularization in Travel, before aligning in Outdoors with the personalized and ludic turn modernism took with Archigram and the “hippie modernism” of the ‘60s and early ‘70s. Considered as whole, however, I wonder if his manga can’t be read in relation to the subsequent adaptation of those design breakthroughs for a consumer market of small, personalized electronics in the ‘80s and ‘90s – the era in which Yokoyama grew up and started making artwork.

Portable audiovisual technologies were central to this shift. Leading the charge was the Sony Walkman. After the Walkman debuted in 1979, it first revolutionized how people consumed music, then how people consumed media in general. Its inventors thought of it as a way to allow people to enjoy music privately inside or on public transportation without bothering others and without cumbersome equipment. Once the device hit the market, consumers started using it outdoors while engaged in activities more vigorous than the “walking” of its name. It not only became a way to listen to music privately (thanks to headphones) while in public (thanks to its lightweight, battery-powered portability), but a way to do so while on the go. Advertisements featured it being enjoyed by joggers, roller skaters, bike riders, and aerobic dancers in the park. As the defining accessory of the “urban nomad,” the Walkman thus engendered a lifestyle constructed around a peculiar organ: the outdoor, mobile, and inner-turned ear that only hears sounds that no ears around it can hear. As scholars like Michael Bull have argued, this combination of auditory mobility and privatization reached a new state of mobility, convenience, and variety with the advent of digital music formats (and thus the elimination of independent physical software) and the release of the iPod in 2001.

In a way, the Walkman was to music what the paperback book was to the printed word. Both facilitated the private yet public consumption of content that previously could only be consumed practically within the confines of buildings, i.e. homes and libraries. Paperback books, like magazines and newspapers, offered words and stories on the go. While (at least in West) children’s books popularized the idea that the books could be a vehicle of combined image and text, not until Sunday color comic strip pages and floppy comic books became popular – with their use of speech balloons, regional dialect, and sound effects – did the portable envelope of the book and magazine encompass images and sound together in significant quotients. It took some time for machines to make the images actually move and the words actually resonate. While portable television sets date to the late ‘50s, I don’t believe there were any that were small or light enough to classify as personal accessories until Sony introduced the Watchman in 1982. Broadcast programming was not the only content adapted to this new portable moving image technology. Handheld video game players first appeared in the mid-late ‘70s, but only took off after Nintendo introduced the Game Boy in 1989. With the rise of smartphones in the ‘00s, portable audiovisual technology went from being a leisure luxury or toy to necessary and ubiquitous personal accouterment.

Has anyone studied how these recent developments have impacted comics? What would a history of Walkman/video game/smartphone-generation comics look like? I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Yokoyama began making the kind of comics he did in the late ‘90s, just as the portable audiovisual revolution was kicking into high gear. To explain Yokoyama’s emergence, the default context to reference is the artist’s background as a painter and the rise of Murakami Takashi’s Superflat and the (selective) recognition of manga/anime by the Japanese art world and Japanese government. Though that might explain why his comics resemble “contemporary art” in the broadest terms, it doesn’t offer much insight into why his practice took the specific shape it did. Why do so many of Yokoyama’s works focus on basic sound and movement? Why is he obsessed with loud noises that you cannot hear? Why does he associate war and destruction with play? Why do so many of his manga eschew character development and plot in favor of game scenarios?

Biography offers one useable detail. As the artist reveals in the interview accompanying the Breakdown Press edition of Outdoors, his one true obsession as a teenager in the ‘80s was the arcade game Xevious, a popular, vertically scrolling, spaceship shooter. He never played home consoles, yet perhaps manga was his way of converting game spaces into portable, private devices – something like a video game novel with original content and images and (virtual) sound. Is New Engineering like a cross between a town-building game and a puzzle game? Is Garden a mixed side-scrolling and isometric perspective adventure/puzzle game? Is the chick in Baby Boom like the baby bird in Tamagotchi? Are World Map Room and Iceland and their telegraphic dialogue like an adventure game in story mode? Yokoyama claims to have played only Xevious and only for a short time. Yet he has somehow tapped into a range of game aesthetics and adapted them for portable, visual books.

4: Musical Pictures

After a few years pursuing this game vector, Yokoyama began creating relatively straightforward narratives under the name of “gekiga.” The first work he explicitly called as such was, I believe, World Map Room, published in 2013, with the recent Iceland its sequel. However, as these works are clearly related to earlier books like Travel, I think it safe to say that Yokoyama has been thinking about the language of gekiga at least since the mid ‘00s, and that gekiga has, in varying degrees depending on the specific work, underwritten his audiovisual experiments as well as his gaming aesthetic.

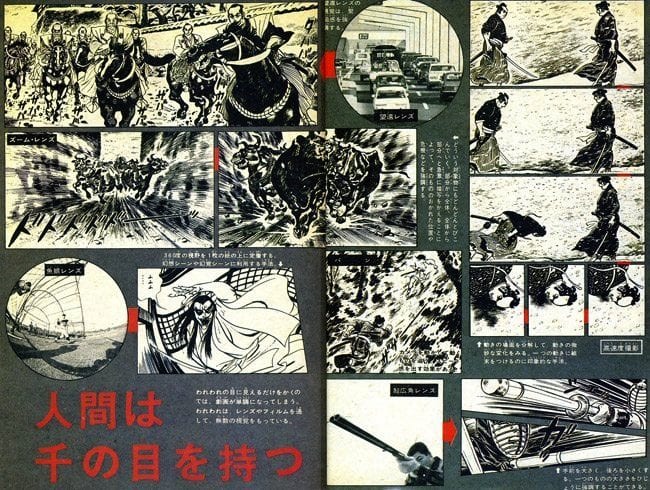

Oddly enough, Yokoyama claims he had no real interest in manga as a child or teen, and that his only exposure to gekiga was random volumes of Saitō Takao’s Golgo 13 – which is ubiquitous in Japan, stocked at barber stores and eateries, as one of the default time-killing manga for men. The relationship between gekiga and established media like cinema, illustration, and photography is readily recognizable, even if under-theorized. In Shōnen Magazine in the late ‘60s, Saitō’s work was celebrated within a modernist discourse of expanded technologized vision, with specific reference to still cameras with various lenses and to filmmaking. On the other hand, I don’t know of any texts that have explored what gekiga might mean post-portable television and post-video games – which is not surprising, given that gekiga has been considered a calcified language and genre for the past thirty years. It took a manga world outsider like Yokoyama to do something new with it.

Yokoyama only occasionally and parodically works in the traditional genres of gekiga (suspense, action, spy, martial arts). Yokoyama’s use of the name nonetheless makes sense if you consider that the focus of gekiga since the ‘60s has been on bombastic displays of male bluster, action, and violence, and that gekiga’s visual language is rooted in an atomistic breakdown of movement and narrative into basic cinematic units and synchronized sound-image signs. Though the genre also trafficked in short stories (especially in its early years), gekiga found its raison d’etre in full-length books and subsequently in magazine serials stretching thousands of pages. Gekiga was, in other words, a comics of grand action and large scale built out from small standardized parts. The play between mini and mega, and between prefab and sublime, was integral to the very comics language Yokoyama worked with.

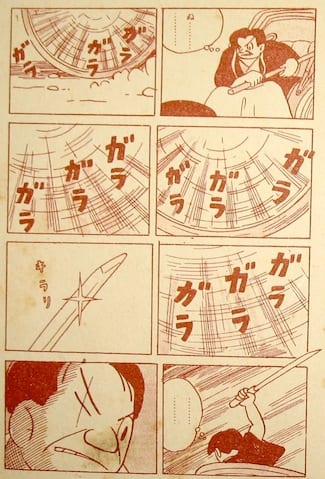

Historically, gekiga’s formal system was not only useful for economizing production for the speedy creation of long narratives for weekly magazine serialization. It also succeeded in perfecting a vocabulary of combinatory figures (articulated over a set of panels) for inducing states of suspense and heightened excitement in the reader. As I argued in “The Eye and the Storm: Gekiga FX and Speed Lines” (International Journal of Comic Art, Fall 2013), the core such figures were primarily optical, with the most common pairing being the excited eye juxtaposed with the object that excites it (as in American horror comics, but more pervasive). Also central was the field of visual effects lines – known in Japanese as shasen (diagonal lines), one variety of kōkasen (effects lines), but deployed so extensively that they fill whole panels and passages, and even serve as the basso continuo for entire books, like Tatsumi Yoshihiro’s Black Blizzard (1956). Such speed lines are not only “visual wakes,” as comics theory traditionally has it. They are also pneumatic disturbances that can be felt by the skin and perceived by the ear. Thus the ease with which exaggerated wake fields turned into blizzards and windstorms and vice versa. Writing a WHOOSH or GWROAR on top of those wakes only accentuates what the emanata itself implies more softly: that the vocabulary of accelerated speed in comics is aural and haptic as well as visual. Last time, I showed how Yokoyama explored this feature in Travel, by making a wordless comic that was nonetheless soundful.

Gekiga’s engagement with the audiovisual did not stop there. It did not stop with amplifying visual emanata with or without written sound effects. Due to gekiga artists’ insistence on visual storytelling through cinematic breakdowns – something that Tezuka previously engaged with, but as one technique amongst others, not as the basis of an entire style – they also subjected the comics soundscape to atomistic breakdown. If cinematic breakdown dictated a single significant figure for each panel – a panel of an eye, followed by a panel of a knife, followed by a panel of a shadow, followed by a panel depicting an impact – it also dictated a localized sound effect for each panel that might benefit from one. Panels in gekiga were thus often sound-images, and their sequencing was a matter of acoustical as well as a visual composition and montage. Even those panels that didn’t represent or imply a sound nonetheless resonated with acoustic “afterimages” due to the prevalence of sound effects in the panels around them. Again, last time we saw how Yokoyama played on this relay between seeing and hearing in cinematic breakdowns in the rain-falling passage of Travel, making the ear as much as the eye an organ of non-verbal perception.

When Tatsumi Yoshihiro complains in A Drifting Life that the wordiness of American comics results in conflicting durations between depicted action and depicted speech, and thus to slackened drama and lack of naturalism, he is making an argument for increased temporal control of the reader’s visual experience through cinematic breakdown, but also for increased synchronization between sound and image. This is very clear in the page from The Demon of Civilization (Kaika no oni, 1955) that Tatsumi frequently used to demonstrate what he was aiming to achieve in the mid ‘50s. Depicting a one-eyed villain readying to cut down another man from a racing rickshaw, it not only juxtaposes eyes and glimmering blades and rotating wheels, but in many panels also pairs those visual details with sound effects. In his 1996 autobiography Reaching for the Star of Gekiga (Gekiga no hoshi o mezashite), Gekiga Studio member Satō Masaaki emphasizes the importance of the sound of the clattering wheels in the above scene from The Demon of Civilization. He additionally identifies rhythmic sound effects (like running and heavily played piano keys), along with the inky fields of speed lines, as what made Black Blizzard so powerful and groundbreaking. Indeed, Tatsumi’s (and before him, and to a lesser extent, Fukui Eiichi’s and Matsumoto Masahiko’s) sound-image system was replicated and elaborated upon extensively by other gekiga artists in the late ‘50s and ‘60s. This is a topic that deserves its own essay (look for “The Ear and the Storm” somewhere in the future); suffice to say here that the “drama” of “dramatic/theatrical pictures” (the literal translation of “gekiga”), as well as the “shock” of “shocking pictures” (in an alternate way to write “gekiga”) was based on carefully coordinated sound effects. It was, in other words, essentially musical.

Interestingly, this idea – that comics could be more immersive by being more musical – was in the air even before the advent of gekiga. Though Tezuka Osamu published many how-to tutorials, his Manga Classroom (Manga kyōshitsu, serialized in Manga Shōnen between 1952-54) is particularly useful for the study of gekiga because it was written when that language was still in a nascent state. I have written previously about how some of the visual-cinematic concerns of proto-gekiga were taken up in Manga Classroom. There’s also a bit on sound, and this bit is doubly wonderful because it frames heightened audiovisuality in manga as an issue also of miniaturization and portability.

“As I was watching the movie The Third Man, I suddenly thought how great it would be if there could be music in manga!” writes Tezuka in a chapter published in 1954. After the movie is over, he goes home, opens a book, and pushes play on his reel-to-reel. “I was leisurely reading, then the music started to get out of sync. It was a quiet scene when suddenly the musical accompaniment of a swordfight barged in. So I pushed STOP.” As a remedy, Tezuka proposes installing a small audio player inside each book. “As you turn the pages, the linked tape will play each page’s music. What a monstrous success I’ve hit upon! After getting rich from selling that idea, I’ll begin adding perfume to each page. And in addition to books with smells, I’ll invent books with televisions so that the images will actually move. Then one day I decided to rig a book so that, when you turn the page to an explosion, it actually blows up – and that was the sad end of me.” Tezuka’s drawing of this multimedia manga shows a fat hardcover volume with a good twenty pounds of machinery inside. Apparently, the artist who got Atomu flying with miniaturized atomic and computer technology could only imagine the expanded comic book as an Edison-age elephant.

While Tezuka is emphasizing more than sound – by including technologies creating smell, movement, and vibration he is responding to a more general desire for immersive experience in entertainment in these years, realized only and only partially in 3-D cinema, which influenced manga as it did American comics – even with just what he says about sound, we can see how Tezuka’s conception of the comics medium’s sensorium differed from what was carried out in gekiga a couple of years later.

Note that Tezuka begins with soundtracking. He doesn’t say he wants the action or speech to be audible. He doesn't say he wants sounds that are already visually represented in comics to now be aurally enacted. Instead, he wants to add to comics something that it rarely has even in written form, which is theme music. He wants comics to have movie-like music, yet he does not express a desire for cinematic sound. That is, he does not suggest that sound in comics should be organized cinematically in the way that images increasingly were in his and other artists’ work. Even his last sound example, the explosion, is not so much about actually hearing the BOOM, and having that sound resonate with other sounds and images, as it is about being rocked bodily by the force of the impact.

Gekiga, in contrast, focused its energies on maximizing local sounds. Despite gekiga’s association with bombast, most of the sounds it corralled and honed were neither caustic nor explosive. Many were quiet, and some (like the sound of a glimmering sword tip) were purely imagined. After all, with gekiga, manga panel frames had become tighter, more focused on the mini rather than mega. Aside from framing shots, paneled images were typically of objects not landscapes, which recommended sounds not soundscapes. Whereas in a landscape the loudest or most significant sounds tends to drown out others, in a breakdown of close-ups aural details are more likely to be represented by the artist and sounded out by the reader just as visual details are more likely to be rendered and seen. Furthermore, because gekiga was premised on the tight control of reader experience to ensure suspense and surprise, the important details had to be both heard and seen distinctly, and done so in the proper succession. As numerous critics have argued with Tezuka’s two-page spreads of cityscapes, concert halls, and senate floors filled with jabbering people, this is not something that landscapes/soundscapes can guarantee. The eye tends to rove more freely.

Tezuka is also not taking into account the reader’s own voice. Gekiga did. Using highly controlled breakdowns, gekiga was able to economize on audiovisual simulation – it didn’t need Tezuka’s elaborate machinery – by relying on the riveted reader to immerse him or herself in local sounds and reproduce those sounds subvocally. The reader became the reel-to-reel player, so to speak. Gekiga also economized, in accordance with the visual focus on eyes and storms, by limiting the range of sounds to varieties of percussion and static, versus Tezuka’s wish for the complex melodies of classical and program music. In Manga Classroom, Tezuka proposes that a portable mechanical orchestra and theater help comics on its way to gesamtkunstwerk; gekiga turned the comics themselves, the panels and drawings and writing, into musical performers. Tezuka wants to add music to comics; gekiga found a way to make the language of comics musical. Tezuka wanted an aural plugin that the reader could hear externally; gekiga came up with an aural program that readers themselves would enact in the course of immersed reading.

Such features are not typically addressed in writing on gekiga. People today (following Garo-associated critics of the late ‘60s, like Takano Shinzō and Ishiko Junzō) tend to describe gekiga in terms of mature subject matter and increased realism. Closer to my emphasis here, designer and writer Ōtomo Shōji insead adopted modern media discourse to champion gekiga as a visual revolution in Japanese comics, referencing cinema, photography, and McLuhan’s idea of media extensions. However, without considering how the ear and voice was an essential part of the new gekiga sensorium, one cannot appreciate gekiga’s success over other forms of cartooning and other comics languages in Japan, nor its ability to hold its own against film and television, nor its impact on Japanese life and behavior in the ‘60s and ‘70s.

Just to give you an idea: There are many photographs of adolescents consuming manga magazines in cafés and public spaces in the mid-late ‘60s, usually as illustrations accompanying articles reporting on the skyrocketing popularity of manga amongst non-children readers. Most of these articles respond to popular worries about what manga reading means for literacy and the future of Japan, before closing with half-baked prospects of a new age of visual literacy. Since it is usually young men that are featured in these photographs, the magazines they are looking at would have been increasingly dominated by gekiga or gekiga-influenced shōnen manga, especially after 1965, when industry leader Shōnen Magazine decided that its continued growth depended on incorporating gekiga into the manga/anime media mix.

Earlier in the decade, a related variety of article expressed fascination with how baby boomer youth, because of their intensive exposure to television and manga, were beginning to speak and act like those media, going as far as to express themselves, not in words, but in sound effects. (See future essay on “Manga and the Television Kid.”) Which is to say, the question of manga’s impact on human literacy and behavior was not just a visual issue; it was an aural one as well. Whatever else the “manga boom” of the ‘60s and ‘70s represents to the history of Japanese culture and society, it was a key part of a revolution that was fundamentally audio-visual. And with manga being consumed just about everywhere young people went – from the schoolyard to inside the university barricade, according to contemporary reports – one could argue that this rewiring of the Japanese sensorium was enabled by the fact that, like the Walkman a decade or two later, manga could be experienced in public and on the go.

Returning to Yokoyama, we have already seen how Travel and Outdoors elaborate on manga’s and especially gekiga’s audiovisual tradition. Let me close with another example from his newest book, Iceland (2016), which is particularly nice since it puts the question of comics’ audiovisual bombast in direct conversation with post-cinematic media. As a sequel to World Map Room, Iceland represents the further elaboration of Yokoyama’s foray into a “neo-gekiga” aesthetic. It is more Kirby-esque, à la Forever People, than ever before. Since Yokoyama has never seen a Kirby comic, it is probably more accurate to say that Iceland is more Steranko via Saitō Takao and via modernist figurative abstraction than ever before. While there are no outright gags in Iceland, the over-the-top-ness of the action and sound effects color the entire manga with a wry sense of humor. Numerous dramatized stand-offs between tough guys over trivialities – a stereotypical trait of mass-market gekiga – further suggest that “neo-gekiga” as a practice is parodic at heart. This can also be felt in the scene in Iceland where gekiga’s audiovisual bombast is most exaggerated. Interestingly, this scene engages with audiovisuality through references to immersive theatrical and video game experience.

The men of the manga go to a bar in search of a friend. The bar is three stories high. As they approach the bar, they hear loud noises – DODODODO – reverberating from inside. Upon entering, they are confronted with an A/V extravaganza of the highest order. Page after page teems with images of booming artillery, rolling tanks, flying missiles, men with guns, spinning blades splitting lumber, jets firebombing cities, warships smashing through waves, and more. Giant sound effects – DADADADA, ZAZAZAZA, BAM BAM BAM, DODODODO, KWEEE – roar across each panel. Two men stand watching these images intently with their hands on their hips. The noise is so loud that the visitors have to ask for the volume to be turned down so that they can converse. Though one panel shows the action occurring on a largish screen of about 6 x 8 ft., other panels give the impression that the video imagery covers the walls from floor to ceiling. The bar’s walls themselves, in other words, are action- and sound-filled panels. Rather than a comics-themed space, Yokoyama offers a comics-engineered space. Since Yokoyama’s work is distantly rooted in Pop Art, imagine being told to view Lichtenstein’s Whaam! (1963) as one should a big Barnett Newman: up close, intently, letting the colors and wakes and sounds flow over you.

Since Japan hasn’t had a tradition of combat-centered war movies since World War II, with the only exceptions – animation and tokusatsu – being genres Yokoyama has no apparent interest in, one is inclined to read this scene in relation to either video games and arcades (which we know Yokoyama once frequented) or gekiga. While most gekiga include long passages of dialogue and aspect-to-aspect changes to establish setting, character, and plot, in the popular imagination it is the moments of high action – modern warfare, mortal combat by fist and blade, hyper-intense sports competition, aggressive fucking – that define the genre. Thus, it seems to me best to understand the bar in Iceland as a full-motion, full-sound, hyper-immersive, architectural version of the audiovisual regime of mainstream gekiga, but with the influence of shooter-type video games narrowing the conception of gekiga to its passages of fighting and action.

The men in the bar are also key. The bar’s visitors describe its patrons as “noisy people,” while a man outside describes them as “scum.” We can see them for what they really are – embedded eyes and ears – and the bar/theater for a supersize version of the rumbling voice box that is at the heart of all comics with sound effects. Indeed, one of the bar’s patrons lounges reading a book. At first, we only see its front and back covers, which are embellished with an image of a continuous range of steep mountains. “How can you read with so much noise?” the visitors ask him. He doesn’t explain, responding only that if the volume bothers them they should ask to have it turned down. At the end of the manga, we see the inside of the book. It is filled with pictures; we see a spread of smoking volcanoes.

This is a strange sort of scene of reading, similar to what Tezuka proposed with his machine manga – in that a series of still pictures are viewed while listening to sound, physically feeling the rumbling, and watching moving images – but shaped essentially by gekiga’s audiovisual tastes and structure. While the old school reader of novels sat with his or her book in silence or amidst soft background music or unobtrusive white noise, the new school reader of picture books prefers an environment of chaos and din, for they supplement and fill out the experience.

How can he read with so much noise? Because the written word and the interiority of thought is not king when he “reads,” and because the human voice of sound effects is a welcome intrusion. Because he is a gekiga-age consumer, and if he can’t take his image-sound system with him on the go into the landscape, he takes his collection of landscapes (in this case, mountainscapes) into a world of sounds and moving images.

Acknowledgements: This essay and its prequel were written with the generous support of a Postdoctoral Teaching Fellowship in the Department of Art, Art History, and Visual Studies at Duke University.