When composed in a certain way, a comic book is something like a Walkman. Of course, comic books (by which I mean any bound volume in the comics medium) lack electronics, and there is no drawn and printed software independent of the paper hardware. You’d be hard-pressed to pick up actual sound waves from its drawn images. Nor will you find a jack to plug in headphones and pipe a soundscape into your ears. Yet no one can deny sound’s place in comics, with their BIF BAM BOOM, pulverizing crashes, and blood-curdling screeches. You, the reader, are the hardware. The speakers are lodged in your throat. Leakage may occur from your mouth, though most of us are capable of keeping the sounds to ourselves, or at least to a soft lip murmur.

Since dialogue, vocal outbursts, and sound effects are represented only visually in comic books – that is, through writing or emanata – it is not the ears but the eyes that are the comic book readers’ audio tape heads. In that sense, the Walkman is the wrong technology. We need something with a moving image or simulation thereof. Old portable handheld televisions once were the best analogues, or perhaps the Game Boy and its spinoffs, though now we have smartphones and thus the entire audiovisual universe in the palm of our hands. Maybe comic books are precocious in that sense: They were our first portable audiovisual entertainments. They were the first medium to allow us to transport a conjunction of sound and movement (albeit virtual) from one room to the other, from indoors to outdoors, from home to coffee shop or train seat.

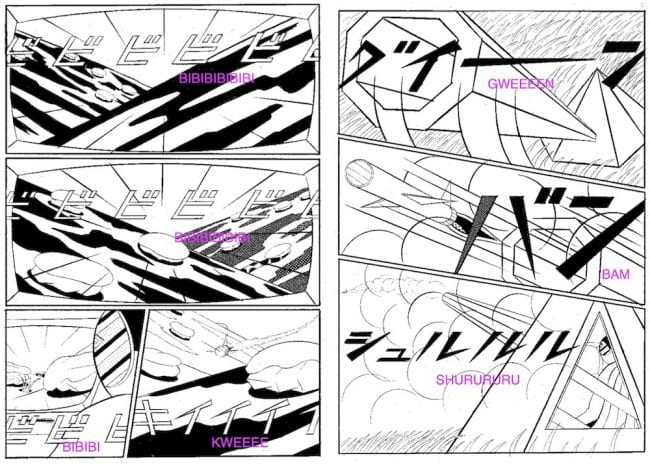

While this is latent in any comic with speech or sound effects, avant-manga artist Yokoyama Yūichi has created a number of works that make a working principle of it. Bombastic sound effects have been a central feature of Yokoyama’s work since his earliest, construction-themed works, collected in New Engineering (2004). Recent works like World Map Room (2013) and Iceland (2017) – an English edition of which was recently published by Retrofit Comics – are crammed so heavily with roaring sound effects that the human figures are forced to navigate not just other people and physical obstacles but also sensorial invasions of visual and aural noise. “This is the loudest comic I have ever seen,” said Leonard Rifas about World Map Room when I gave him a copy recently. Interestingly, Yokoyama has described noisy World Map Room and Iceland as works of “gekiga” – a style of manga that is usually defined according to subject matter (mystery, gangland action, samurai aggression), the sidelining of laughter, and a heightened realism, but in this case seems to refer to a specific comics vocabulary emphasizing intensified visual and aural experiences around scenarios of masculine bluster.

Meanwhile, an earlier work, Outdoors (2009) – which will also appear in English this year, from Breakdown Press – represents an exercise in comics listening of a softer sort. Though not constructed or intended as a reflexive work in the “understanding comics” vein, Outdoors foregrounds the audiovisual funkiness of comics in a stripped-down and demonstrative form. Outdoors is not a work of gekiga, says the artist. Yet it, too, can be read in relation to the audiovisual tendencies that became pervasive in Japanese comics because of gekiga’s influence over the course of the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s.

As innovations in one medium often occur by rethinking that medium through new developments in other media, it is worth keeping in mind that Yokoyama’s peculiar manga aesthetic emerged in the late ‘90s and early 2000s, at a time when handheld audiovisual and gaming devices were reaching a new height. Gekiga, on the other hand, had been a more or less dead genre since the ‘80s, living on only through reprints of old classics and a handful of popular new titles that were employing its codes for convention’s sake. If Yokoyama’s “neo-gekiga” represents a revival of gekiga, it is so through the matrix of this new audiovisual age, as will be argued below.

The results are oftentimes comical; if attended to closely, they ask us to expand our idea of how comics function. Some of Yokoyama’s best-known works, like Travel (2006), are tour de force demonstrations of the power of comics as a visual narrative medium. As such, they appear to confirm a discourse within comics historiography and criticism that describes the medium in its most essential form as “sequential panel art,” or some such variant thereof. It is a discourse that aligns visual experience in comics with pictorial reading and non-figurative and non-verbal graphic appreciation, and links the rise of modern comics with the advent of visual technologies like chronophotography and cinema – all the while marginalizing, ignoring, and sometimes outright denying the importance of sound and speech in the medium. What we find in Outdoors and Yokoyama’s recent “neo-gekiga” works, in contrast, is the artist playing with the fact that visual experience in comics is often deeply tied to the ear and, through the ear, the human voice. These aural and vocal qualities, once recognized, can also found to be operating in Yokoyama’s super-visual, wordless works.

As argued elsewhere, I suspect these aural/vocal qualities are latent, if not suppressed, in many abstract and wordless comics. In Comics and Narration, Thierry Groensteen, expanding on Andrei Molotiu’s work, proposes two broad categories of abstraction in comics: abstract comics proper (non-narrative and non-figurative) and infranarrative comics (figurative but non-narrative or massively elliptical, related to what Scott McCloud calls “non-sequitur” panel relations). Both categories presume that the rejection of narrative and/or figuration is a prerequisite for extensive abstraction. They also presume that abstraction is primarily and finally a visual matter, ignoring (but for the occasional empty speech balloon) the verbal, aural, vocal, and integrated audiovisual qualities of most work in the medium and the abstraction that can and does stem from that basis. Yokoyama’s work shows that the theory and discourse of abstract comics – even that of comics in general – needs to be expanded beyond these biases, at the very least to include sign systems and sensory apparatuses related to hearing, writing, and speaking/vocalizing. The present essay and its sequel is my attempt to begin theorizing such “audiovisual abstraction,” using Yokoyama’s work as a case study.

1: The Ballistic Ear

Since at least Travel – a wordless manga set almost entirely on a high-speed, long-distance train resembling Japan’s bullet train – Yokoyama has engaged with what Paul Virilio termed “ballistic vision”: seeing as a bullet or other projectile does, hurtling through space face-first towards a destination, typically with penetration or destruction as the end goal.

Yokoyama’s embrace of vehicular and technologized vision, however, is not limited to the head-on view. He is even more keen on lateral movement, in seeing the landscape rush by as one moves parallel to it, and in the sliding planes of space that result from different objects being at different distances from the mobile viewer. Visual abstraction in Yokoyama’s comics often builds on that basis, generating geometric rhythms and entropic figures that repeatedly draw the reader into the diegesis, then push them out to the picture plane, and back. Play with lateral movement also leads to the production of analogies between the language of comics and technologies of seeing and moving – which is important to recognize because it establishes that abstraction in Yokoyama’s work is not just about pen-on-paper, but rather is almost always inflected by technology.

For example, in Travel, lateral movement is typically rendered from the perspective of the train’s passengers looking out at the landscape through the train’s windows; the windows, in turn, frame both the passenger/viewer and the landscape as framed still pictures. This double framing often results in an implied analogy between vehicularized vision (mobile viewing through frames) and sequential panel art (seeing motion across a series of frames). Underwriting this analogy is not so much an insight about comics in general (most comics are not about vehicularized vision, even if many are about movement), but rather the cinematic turn that Japanese comics took in the ‘50s around the emergence of gekiga, more about which later. Likewise, if Travel seems like an extended homage to Futurist paintings and prints, German “city symphony” films of the ‘20s, and the mechanomorphs of Dada ballet, this has less to do with any deep interest on the part of the artist in the historical avant-garde (Yokoyama claims ignorance), and more with his choice to regard cinematism in comics as involving, not just moving pictures, but also moving eyes.

With Yokoyama’s next book, Garden (2007), featuring a group of men traversing a world of bizarre objects and structures like an obstacle course, the relationship between vision and technology becomes more complex, mainly due to the introduction of photographic apparatuses and photographic documents.

Already in Travel, on one page a man is shown photographing the passing train with a Polaroid camera. This is expanded in Garden, with one human taking snapshots at intervals throughout the entire manga, generating visual correspondences between comics panels and photographic prints, and suggesting a relation between the sequential panel maker (the comics artist) and the camera-toting tourist or train-watching otaku.

The more memorable photographic devices in Garden assume a quasi-military and surveillance form. Near the manga’s mid-point, bomber-sized airplanes roar through the air. Suddenly, giant flashes go off on their fuselages. When their bomb holds open, massive caches of photographic prints fall through the sky. The manga’s humans assemble as many of these prints as they can, creating a giant map of the world they inhabit. While Travel presented a visual regime of bullets and rushing windows through civilian technologies of vehicularized travel and recreation, Garden instead offers something like a gamer aesthetic by crossing surveillance and war technologies and mapped play spaces.

This shift from an early modernist paradigm of motion-machine vision (trains and cinema) to a postmodernist one of games (play spaces, video games, and remote control wars) informed Yokoyama’s work when he returned to vehicularized vision a couple of years later in Outdoors, a web-comic (though conceived and hand-drawn as usual) published in book form in 2009.

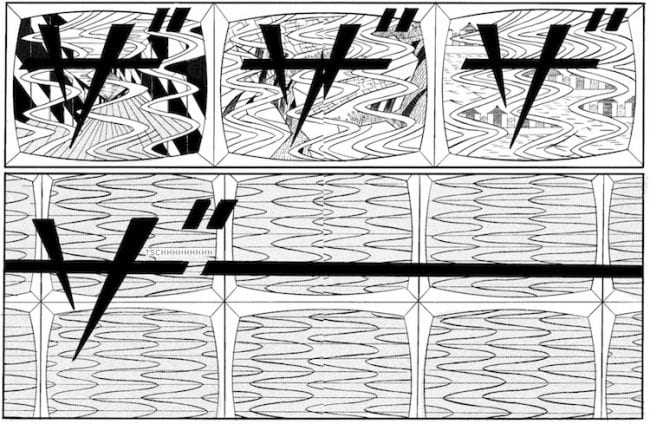

The first segment of Outdoors opens with a human sitting in a small pyramidal structure furnished with nothing but a chair and a console equipped with steering handles, a video monitor, and (we learn later) a photographic printer. The next twenty-four pages show him steering a drone missile over land, through bushes, under fallen trees, through a flock of birds, and finally into the water, where the adventure ends in a crash. Intermittently, the man presses a button to generate a still printout of what he sees on the drone’s video feed. Since the content of these photographs is insignificant – a fruit tree, a grasshopper, flowers, a bird – their purpose in the manga seems more about generating play between forms of still and moving imagery and their corollary technologies, and deriving fun from the perverse use of military technology for end-in-itself, leisure and aesthetic purposes.

If visual technologies and technologized vision are thus everywhere in Yokoyama’s work, so is sound. True, Travel is wordless, and sound is not a major feature of Garden – though when there is sound, usually it is loud. When the flying fortresses arrive to map the world with their cameras, note that their mechanized uber-vision enters the manga with a deafening roar. This goes back to Yokoyama’s earliest works, where odd happenings were presented to the eye with theatrical displays of sound. His first book, New Engineering, is filled with machines hammering and grinding, and massive geometric shapes moving, almost always accompanied with sound effects in oversize katakana. The noise returns with Outdoors – but with a difference that reflects what Yokoyama had been up to in the meantime with Travel and Garden.

While the early, New Engineering pieces focus on land works, and the building and destroying that construction activities entail, the soundscape of Outdoors is linked to the zooming mechanical eye that Yokoyama had established in the vision-centric universe of Travel. Outdoors thus poses a number of interesting cross-media and cross-sensory questions. Like: What is the sound of an eye hurtling through the space? What is the sound of photographic and video technologies being converted into print and panels? The mobilized eye, Outdoors suggests, is not a disembodied flying organ. It is linked to a whole network of sensory inputs that are collectively forced to cope with the intensification of experience in a world ruled by herculean and speeding machines.

In Travel, Yokoyama could get away with ignoring the modern noise-ridden soundscape by setting the manga in and around the Japanese bullet train. Yet, as anyone who has rode the bullet train knows, the experience is in fact not very quiet, due to the incessant whooshing noise. Sonically fairly homogenous, yes. But quiet, no, and certainly not silent – and this is where it’s important to not collapse “wordless comics” with “silent comics,” as writers sometimes do. If Yokoyama has a penchant for high volume, he also knows that noise is best appreciated when controlled. Note that, even at their loudest, Yokoyama’s soundscapes are exceedingly clean and articulate. Sound is subject not only to the neat geometry of Yokoyama’s graphics but also to the basic formal nature of writing. Since he is dealing with written and visual representations of sound rather than actual auditory sound, even the loudest din has to be converted into discrete phonemic written characters. Even the TSCHHHHH static of the interrupted video feed in Outdoors or World Map Room is elegantly contained in a single katakana character and a smoothly tapering dash. Graphics are Yokoyama’s way of musicalizing (i.e. aesthetically organizing) noise.

This same principle can be applied to Travel, even though the manga is devoid of writing. Certain parts of Travel make it clear that Yokoyama wishes the reader to listen into to the manga’s hyper-visuality. The manga’s endless speed lines and visual wakes, for example, suggest a constant static of whooshing; a non-verbal TSCHHHHH pervades the book. Meanwhile, it seems that Yokoyama thought other varieties of sound (specifically percussive ones) needed more obvious aids to resonate. When rain drops begin pounding the train’s roof halfway through the book, Yokoyama decides he needs to do more than just showing them crashing and splaying. After two horizontal panels depicting falling rain, he shows two panels each with a man look towards the roof. On the next page, after three horizontal panels showing rain hitting the roof, a detail of an eye and then a detail of an ear – an injunction for the reader to look in order to hear.

This manga might be wordless, this passage states, but it’s not silent. More deeply, Yokoyama is showing how the visual breakdown of motion (on which Travel’s ambitions as an experimental project are ostensibly built) is also an aural breakdown of the soundscape. We know paneling as a way to organize time and space; it is also a way to organize sound. Usually paneling is employed in that capacity in tandem with written sound effects, but here we see how it can also operate musically on its own. Film theory has extensively theorized the relationship between the cinematic shot, cinematic montage, and sound editing. Comics, both under the influence of cinema and otherwise, deserve a related theory.

If Yokoyama’s work is musical, what kind of music is it? Writing about non-figurative abstract comics and mainstream artists like Steve Ditko, Andrei Molotiu has usefully shown how comics layouts can be understood in musical terms of melody and rhythm, terms which he uses metaphorically to describe periodic visual patterns and compositional structures. He calls this “sequential dynamism” and frequently uses vocabulary from opera and Western classical music. (See Molotiu, "Abstract Form," in Critical Approaches to Comics, 2012.) One can find similar things operating in Yokoyama – Baby Boom (2009), for example, is an extended exercise in optical and choreographic rhythms – though in most of his works patterns and structures often progressively devolve into figures of near-illegible visual confusion. Travel, for example, plays extensively with the relationship between rhythm and entropy. And when the visual and aural are correlated, the “musical” forms they resemble most – drone and non-rhythmic percussion – are closer to varieties of nonperiodic noise.

Drone-wakes and beat-breakdowns in Travel: If the drone of whooshing speed lines are the aural corollary to the accelerated and ballistic eye, then the non-rhythmic percussion of raindrops corresponds to vision momentarily removed or abstracted from the time-space continuum through paneling. On the one hand, there are multiple passages showing full faces and full landscapes striated with speed lines within single panels and across multiple panels. On the other, the attentive listening pages (the rain drop pages) presents a focalized eye and a focalized ear, each contained in their own panels, juxtaposed with other panels showing the objects making discrete but irregular sounds. In the first example: bodily immersion in the undifferentiated and environmental noise of speed. In the second: attentive looking and attentive listening directed at the focalized sound of singular rhythmic events. Sometimes he overlaps and interlocks the two.

In this essay’s sequel, I will explain how this articulation of noise-forms visually and aurally speaks to the legacy of gekiga. For now, it’s enough to recognize that vision and sound are intimately linked in Yokoyama’s work (probably more than they are in most comics), such that it makes little sense to speak of abstraction or musicality in purely visual terms.

2: The Blurting Eye

The first segment of Outdoors, showing the drone-missile racing across a landscape, foregrounds the ballistic ear. The second segment is instead organized around the attentive ear. It takes that single-page injunction to attentive listening in Travel and turns it into an extended meditation on audiovisual appreciation in comics. Unlike Travel, however, Outdoors includes written sound effects. It thereby forces to the foreground a different and more curious facet of audiovisuality within the comics medium: the fact that between the eye and the ear in comics typically stands another set of organs, namely those located in the reader’s mouth and throat.

Before continuing, it is important to clarify the function of the humans in Yokoyama’s work. Lacking personality and interiority as most of them do, it is hard to call them “characters” as one usually would in describing comics. They are more like “human figures” in the way the term is used in modern art: as conventional scaffolding (portraiture in painting, human action in comics) for carrying out formal experiments. In Yokoyama’s case, such formal experimentation does include visual abstraction in the traditional sense. But as we have seen, vision and sound are intimately linked in the artist’s work, such that it is not possible to speak of abstraction in a reductive, single-sensory way. Hence, the scaffolding his “human figures” provide is not just for abstraction in visual form (shape, mass, color, perspective, movement). Instead, they serve as vehicles to explore connections between the visual, verbal, and vocal as they function within comics making and comics reading.

Note that Yokoyama’s sound effects are almost never of people or animals making vocal noises. There is no yelling, crying, squawking, or howling, though there are birds with their beaks ajar and wolves with their mouths agape. When Yokoyama uses speech balloons, the dialogue is always flat and rarely modulated by smaller or bigger typography or punctuation. In other words, not only do machines, nature, and inanimate objects dominate his aural universe; they are the only entities allowed to have expressive sonic characters, i.e. “voices.” Just as it is hard to call Yokoyama’s humans “characters” even though they act and talk, so it is hard to say that they have “voices” even when they are speaking and communicating.

How strange and paradoxical, then, that the human voice is everywhere in Yokoyama’s comics. It is part of why his comics are so odd and wonderful. Even wordless ones, like Travel, seem to be responding to this ubiquitous vocality. His wordless comics are wordless, I suspect, not only to show off the possibilities of comics as a visual medium. They are wordless – and one might be able to say this about wordless comics in general – also to keep the human voice at bay. For there is no sound in comics that is not a human sound, and therefore to create a truly machinic and post-human comic (as Yokoyama seems to want to do), sounds, whatever their source, must be suppressed. Wordless comics, especially in their “purest” form as metamorphic abstract comics, typically deny the importance and power of sound in comics. At one level, this is simply a consequence of their rejection of verbal signs. But in some cases, this suppression can also be attributed to a conventional high modernist antipathy toward intermedia miscegenation, and perhaps even an unconscious anxiety about the vulgar human body that all sound effects, willingly or not, smuggle into comics.

Readers of Outdoors will probably sense what I did while translating it, and that is that the manga’s second segment is best understood as a visual sound poem. Again, there’s no story: three different human figures enter three different motorhome type dwellings, take their respective seats, and listen to the rain falling first in drops then in sheets upon the roofs and awnings of their dwellings. Once it floods, they drive their small, motorized abodes away.

While no more character-like than the humans in other Yokoyama manga, the human figures in Outdoors serve a unique function: to plant ears and eyes inside the diegesis as conduits for the readers’ own audiovisual experience. Why do these men occupy these strange dwellings? So that there can be comic book eyes and comic book ears inside those structures when it starts raining. Why are each of the dwellings stylized so differently? So that each may resonate differently when the rain falls. Sure, the dwellings’ designs derive loosely from a history of avant-garde architecture. But the building materials and their subjection to the elements speak instead to experimental music and poetry. These funky structures look like houses, and turn into vehicles in the end, but they are essentially musical instruments. Yokoyama has chosen building materials as much for how they sound as for how they look. As a paper architect, he is also an acoustical engineer.

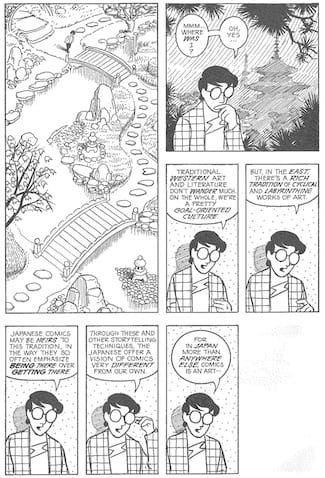

Though I cringe to admit it, there is something stereotypically Japanese about this segment of Outdoors. As Scott McCloud pointed out in Understanding Comics (1993), there is a heavy quotient of “aspect-to-aspect” transitions in Japanese comics, with “aspect-to-aspect” referring to breakdowns that function to shift attention from one aspect (character, detail, space) of a scene to another rather than presenting linearly segmented movement and time. McCloud states that this transition type has been “an integral part of Japanese mainstream comics almost from the very beginning,” though, in fact, their pervasiveness only dates to the advent of gekiga and the cinematic language it adopted in the mid-late ‘50s. They were the product of a process of technological remediation at a particular juncture in the history of manga.

That aside, McCloud says some useful things about this transition type’s aesthetic effects. To begin with: “Most often used to establish a mood or a sense of place, time seems to stand still in these quiet contemplative combinations.” After explaining that longer page-counts in manga publishing make a high ratio of such sequences materially possible, McCloud proposes that their predominance reflects a cultural emphasis on “being there over getting there.” Western culture is “goal-oriented,” he says, while Oriental culture appreciates wandering and getting lost. Oriental culture appreciates silence, intervals, and fragments, for they allow the reader/viewer/listener to appreciate elements in themselves and in relationship to other elements independent of their narrative context. Amongst McCloud’s examples are a Japanese garden, Hokusai’s wave, a shakuhachi player, and the impact of Japanese musical structure on modern music in the West. Note that, though McCloud’s cataloguing of panel breakdowns relates only to the visual, and that aspect-to-aspect breakdowns are premised on “quiet contemplation” of purely visual images, he includes examples from music and sound to explain this breakdown type’s aesthetics.

Now, while Outdoors is not dominated by aspect-to-aspect transitions – the difference between such transitions and others involving visual leaps (basically the whole range of cinematic cutting and then some) is notoriously ambiguous anyway – most of the manga’s second segment foregrounds the kind of aesthetic appreciation that, according to McCloud, characterizes Japanese comics in general. The rain sequence of Outdoors demonstrates how, in order to produce the kind of meditative experience in question, a variety of breakdown types can be used; a sequence of wordless “aspects” is not the only way. What is necessary is not so much a certain type of panel transition as a foregrounding of the phenomenological aspects of comics reading over and above narrative context. When panels assert themselves as supports for attentive looking and hearing, as is frequently the case in Yokoyama’s work, reading becomes an activity focused on the appreciation of the layers of sensation that accrue through exposure to a succession of visual and sound elements. Of course, this is not just limited to comics; as an example of the Orient’s “wandering” aesthetic, McCloud offers a tall panel of a Japanese garden. But as any student of Japanese haiku or garden design knows, aesthetic experience in the Japanese garden is not just about meandering pathways and the changing vistas they offer. The garden is also equipped with seats and verandas for visitors to stop and listen to the natural, animal, and insect sounds that seasonal changes bring into the garden’s highly manicured setting. What is the second part of Outdoors but a manga of seats and verandas?

By saying that Yokoyama is interested in this sort of paradigm, I am not calling him a Zen aesthete. After all, the majority of Yokoyama’s soundscapes are characterized by a noise music aesthetic of aural assault, rather than one of quiet listening. Furthermore, quiet listening within modern Japanese aesthetics is hardly limited to Zen. For example, in the years just before Yokoyama started publishing manga, there emerged a whole genre of avant-garde music in Japan, known as onkyō (simply “sound,” or literally “sound reverberation”), organized around attentive listening to soft electronic sounds. What ethnomusicologist Lorraine Plourde has said about onkyō – that its tropes of quietness and stillness are more a response to modern urban cacophony and avant-garde modernism than they are to classical Japanese aesthetics – also applies to Yokoyama’s manga. (See Plourde, "Disciplined Listening in Tokyo," Ethnomusicology, Spring/Summer 2008.) At the most basic level, by attending to sound in different ways, Yokoyama is simply pursuing abstraction within the wider field of avant-garde aesthetics, unswayed by the ocularcentric bias of Western formalism in the visual arts.

While onkȳo performances typically dictate what Plourde calls “disciplined listening” on the part of the audience – involving stringent restrictions against bodily movement and a total ban on the human voice (talking, coughing, or clearing the throat is not allowed, even thinking to oneself is a no-no) – Yokoyama’s comics liberally engage the human body through sound. At first glance, they seem to do just the opposite. Like good disciplined listeners and lookers, Yokoyama’s characters in Outdoors do not speak. Judging from their deadpan expressions, we have no reason to think that their thoughts wander to other images and sounds. Not just outwardly, but also inwardly, the human voice is suppressed. However, while in onkyō appreciating sounds means attending to how they reverberate in the listener’s ear, in comics there is no actual sound to hear. The sound must be read, and to appreciate read sounds means attending to how those sounds reverberate in the reader’s throat. In a way, Yokoyama touches on a longstanding problem in avant-garde music premised on attentive listening: the ineradicable presence of the body across which all heard sounds reverberate. Because he works with written sound effects and thus with phonetic writing, this ever-resonant body is localized, not in the ear, but rather in the organs of human speech.

To get at this situation, let us consider the nature of comic book sound effects more closely. Above I wrote that Yokoyama is a sound engineer. Since he is so only as a paper architect, he is therefore only a paper sound engineer. Most people have enjoyed, at some point in their lives, listening to rain fall on actual surfaces. But what if these materials and surfaces were merely drawn in ink on paper and thus their sonority and timbre had to be notated and imagined? This came home to me while translating the rain segment of Outdoors – where “translating” means deciding what alphabetic combinations to ascribe to each Japanese katakana sound effect. What does light versus heavy rain sound like when it falls on hard versus soft surfaces? How does that sound change for an ear outside versus inside a structure?

For the original Japanese, these questions are less urgent. Because of the limited phonetic range of Japanese kana, onomatopoeia tends to be fairly broad in the range of sounds it can encompass. The actual sound that Japanese readers imagine and vocalize to themselves depends a lot on what object or action the onomatopoeia is coupled with. They sound out the image, so to speak, and image out the sound. In contrast, with English and other languages based on alphabets, due not only to their wider phonetic range but also to the loose combinatory nature of alphabets, onomatopoeia must generally be more specific. Hence, as a translator, it is not enough to read katakana and think about legible correlates for a non-Japanese speaker. One also needs to consider the visual materials to which those sound effects are appended, and consider them in a tactile way. Far more than the average reader, the translator has to sound out the drawing.

For example, is that roof on page 65-66 of Outdoors made out of metal or synthetic plastic, and is that metal/plastic thick or thin? While katakana PA-RA, PA-TA, BA-RA, and BA-TA may suffice to cover the entire range of materials without sounding flat and limited, alphabetic notation requires more variety. Furthermore, whether TONG or TONK is better also depends on how your mother tongue is shaped. Do you read the Roman alphabet through English, Italian, or French, and which English, which French? This is an issue not only for the translator, but also for the reader. How one reads a sound effect is highly dependent on how one speaks. There is no written sound that is not a human sound, and that holds true for both the artist fashioning the sound effects and the reader who reads them. For the translator, this means that sound effects have to be approached less like standard textual translation and more like vocal notation. Since every sound effect, even when its source is non-human, must be translated into human phonemes, translating sound effects is an exercise in trying to properly shape the reader’s tongue and lips through the right concatenation of alphabetic letters. What this also means is that even an aural world as non-human as Yokoyama’s – dominated by zooming machines, assaulted objects, and torrential weather – is a concert of human voices.

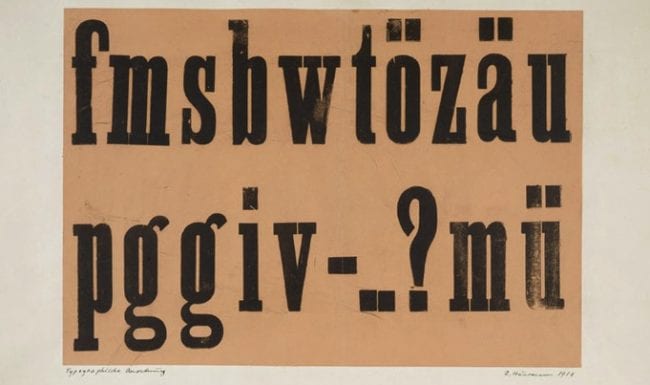

When thinking of Yokoyama’s soundful manga and the history of aesthetics to which they belong, one might go back to Luigi Russolo’s Futurist art of noise, since Yokoyama is an artist who has filled whole sequences gleefully with sounds of industrial and electric modernity. In contrast, the rain passage of Outdoors could be compared to John Cage’s appreciation of non-musical sound extracted from daily appliances in Water Walk (1959). But considering the inescapable vocal underpinnings of comic book sound effects, Futurist parole in libertà (words-in-freedom) and Dadaist bruitism (noise poetry) provide more apt reference points. Imagine Marinetti belligerently barking ZANG TUMB TUUMB in London or Hugo Ball spluttering ZOKE ZOKE at the Cabaret Voltaire, with the artist in each case trying to overcome the parochialism of human language and standards of vocal propriety by mimicking the cacophony of a world overtaken by mechanized work, transport, and warfare. Transposed to the Zen garden, imagine a garden full of voice actors hiding in the hedges and behind stone lanterns, hollering out phony bird call, cricket chirps, flapping carp splashes, and the bamboo deer scarer’s periodic clacks – not so meditative after all.

In Dumbstruck: A Cultural History of Ventriloquism (2001), Steven Connor offers some ideas that are helpful in thinking about what is going on here beyond the usual machine-man discourse of modernism. He writes, “Children develop very early on a pleasure in vocally reproducing the sounds of the world – the creaking of doors, the wailing of sirens, the pattering of rain. This is more than onomatopoeia, which is to say, more than mere imitation. When one vocalizes a sound, one gives to it one’s own voice, in order to give it its own voice.” This leads to an “animation” of the inanimate and non-human worlds, “an enactment of the possibility that things in the world might be capable of and characterized by speech,” and therefore an imparting to those things with “the same kind of interior self-relation as is possessed by all entities that have a voice.”

For Connor, the animating power of onomatopoeia has profound existential ramifications, and is central to how the human relationship to the world is defined by our capacity to speak. As both playing children and avant-garde poets know well, this process is also inherently comical. The funniness of humans acting like objects or machines has served as a baseline of the modern philosophy of humor since at least Bergson. No art history book fails to describe how mechanomorphic imagery was a core part of Dada humor. Why shouldn’t the same also apply to sound? Are not Futurist and Dadaist sound poems basically mechanomorphic sound performances, and their written version mechanomorphic sound images? They play on the absurdity of humans endeavoring to sound like machines. They make a ridiculous show of the flesh-and-bone limits of the human vocal apparatus, thus downgrading the elevated arts of song to vulgar oral nonsense.

Comics with sound effects operate in a similar way, and demonstrate that this comedy need not be limited to industrial and war sounds. “Listening outside a cartoonist’s studio,” writes Mort Walker in The Lexicon of Comicana (1980), “you would constantly hear him vocalizing the piece of action at hand . . . a bat hitting a ball, FWAT! . . . a foot kicking a garbage pail, K-CHUNKKK! He will try many sounds before he settles on the one that satisfies him. Then he will add more meaning to the sound by animating the lettering.” This is elementary comics language stuff, of course. All the more odd, therefore, that comics theory rarely goes even this far in acknowledging the vocal dynamics of comic book sound.

This vocal performance doesn’t end in the studio. Through an act of ventriloquism, it is also reproduced in the reader. While the person making the vocal sounds is hidden unseen off-page, their voice is everywhere perceptible in the sound effects and everywhere heard in the act of writing and reading. Not that the actual grain of the author’s voice is perceived, but rather the general fact that he or she has a human voice, which thus elicits enactment through our own. Most cartoonists perform this ventriloquism through human dummies: the BIF BAM BOOM of men fighting is classic in American superhero comics, as is the scream in horror comics and the gun fire and explosions in war comics; most sound effects have a human agent attached to them. Yokoyama is special in that many of his panels absent the human altogether. Machines and objects seem to speak on their own, making the mechanomorphic juxtaposition of voice and machine all the more obvious and comical. It is like a ventriloquist making a coffee pot or vacuum cleaner speak, rather than an anthropomorphic doll. This is the “animation” which Connor writes about, but without a human face or body to personify the vocalizing objects and naturalize the performance.

Many of Yokoyama’s pages are rough scores for human beatboxing. If you doubt this, I invite you to read New Engineering or Outdoors out loud. The performance should be crude, to reflect the fact that most readers don’t have beatbox talents. The human body below the sound effects should be as obvious as a bald pate beneath a bad toupee. Actually, “out loud” is probably going too far; it is a misrepresentation of what comics reading really involves on an aural plane, since most of us read comics like we do other books, which is to say silently. We read the sound effects subvocally, with no more than a light vibration in our throats, around our tongues, and across our lips. Yokoyama, by employing sound effects so “loud” that they oftentimes obscure the image, invites the reader to go further – to open their mouths and let the phonemes fly, and let the Dadasitic absurdity at the heart of the comic medium’s audiovisuality flourish in full bloom. As the artist ventriloquizes the comics page – “throwing” the human voice into a drawing, thereby animating it, while keeping the human body which provides that voice off-stage – so the comics page in turn ventriloquizes us, the readers. We come to hoot and blurt a mutilated form of Yokoyama’s own ZANG TUMB TUUMB. Through the proxy of the written sound effect, Yokoyama wages war games and calls forth rainstorms inside your mouth.

Which reminds me: Yokoyama is an exact contemporary of Tōhō Rikimaru, a self-described mandokuka, “manga reader/reciter.” Rikimaru, whose professional name is a pseudonym that means something like Strong Man of the Orient, aspired to be an animation voice actor. He went to school for it in the ‘90s, but failed to find a job. In need of a living, he took his vocal skills to the street, or more accurately to the park. Inside Inokashira Park, in the hip neighborhood of Kichijōji in western Tokyo, set up a few plastic stools (the kind made for sitting and washing yourself before getting in the bath) and laid out a dozen or so manga volumes on a plastic sheet. For a few hundred yen, Rikimaru reads to you the manga of your choosing – not as a relaxing bedtime story or poetry recital, but as if the manga was a script for animation voice acting. He not only reads the speech balloons dramatically with mock hyper-masculine and feminine voices. He also performs the screams and cries and pants and grunts, as well as the non-human and non-animal sound effects, as well as the crashes and crunches and screeches and explosions, all at full volume. In animation, these latter noises would be produced with machines and objects. Rikimaru, a one-man manga sound effect machine, does them instead with his voice.

The performance in person (or on video) is as ridiculous as it sounds, especially because Rikimaru makes no attempt to naturalize the speech or vocal outburst or make the non-human sounds sound less human. The performance is particularly ridiculous when Rikimaru is asked to do manga in the legacy of gekiga. No one would call Dragon Ball a work of gekiga, given its humor and cartoony characters and squash-and-stretch action. Nonetheless, the manga’s obsessive focus on martial arts showdowns, crunching fists, speed lines, and ripping explosions clearly derives from sports and martial arts gekiga and their shōnen manga offshoots in the ‘70s. Fist of the North Star (go to 2:58 in this video) is more solidly in the gekiga tradition, with its realistically proportioned characters (I am not talking about their bulbous musculature), its unadulterated violence, and its hyper-masculinity. Rikimaru’s performance of both is superb. He brings out not only the ridiculousness of the manga’s bombastic action and dialogue, but also the ubiquitous and absurd vocality of a manga genre dominated by overblown sound effects.

The animated versions of either manga are themselves entertaining and extreme affairs. But there the bombast is naturalized by being presented through a medium where over-the-top voiceover is the norm and where non-human sounds are produced by machines. By relying only on his voice and hands, Rikimaru essentially “de-animates” animation. Trained as a voice actor, he is able to simulate animation’s voice track, yet does so without the visual screen behind which the voice actor usually hides. Instead of a moving drawing talking ridiculously, you have a ridiculous man talking like a moving drawing. In order to simulate zooms and reverberating impacts, he rushes the book at the viewer’s face and shakes it about. Ten or twenty years after gekiga’s demise, Rikimaru revives the medium in loving parody, physically foregrounding its cinematics and its vocality through his own hands and voice. Though coming from animation, he has tapped into the audiovisual ventriloquism that shapes writing and reading in all but the most rigorously non-aural of comics.

Comics are a strange form of audiovisual entertainment indeed. Next time we will consider the third term of my proposal at the beginning of this essay: that comics, and especially Yokoyama’s comics, are a form of portable audiovisual entertainment. We have established that Yokoyama is into mobile eyes and mobile ears. How about mobile books and mobile devices?

(Go to Part 2).

Acknowledgements: This essay and its sequel were written with the generous support of a Postdoctoral Teaching Fellowship in the Department of Art, Art History, and Visual Studies at Duke University.