RoboCop moved from film to comics with an almost pre-programmed inevitability. A more-than-human crime-fighter with an instantly recognizable look, introduced the same year Mike Baron and Klaus Janson launched the Punisher’s first ongoing series and Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons concluded Watchmen, the character allowed for a blend of anti-heroics and heightened violence common to the most popular genre comics of the era. And sure enough, since RoboCop premiered in 1987, not one but several publishers have released comics spin-offs: Marvel, Dark Horse, Avatar, Dynamite, Boom! But while this may have been a near certainty, there’s still a measure of irony in it. The first film, from director Paul Verhoeven and screenwriters Edward Neumeier and Michael Miner, doesn’t just debut a new action hero; it also suggests other iterations may be clumsy, cynically produced, and prone to misfiring.

Early in Verhoeven’s film, Alex Murphy (played by Peter Weller), a police officer in a Detroit overrun by crime and capitalist excess, nearly dies after an encounter with a violent gang. Omni Consumer Products (OCP), a corporation with a contract to fund and run the Detroit Police Department, revives Murphy, giving him new life through cybernetic enhancements. But when Murphy learns of a criminal element within OCP, he must see justice served and maintain his grasp on humanity in the process. He’s also forced to contend with ED-209, another attempt at robotic policing.

ED-209 is blunter, less agile, and less inventive in its design (which helps Murphy avoid destruction by its hand). Years removed from the first film, it’s tempting to look at ED-209 and see Verhoeven anticipating the franchising of RoboCop—the separation of RoboCop the intellectual property from the voice and style of the original film—as a malign act. The film’s hostile and often hilarious anti-capitalism makes such a reading easy too. But even if a viewer doesn’t grant Verhoeven, Neumeier, or Miner that foresight, ED-209 still plays like a warning: look closely for defects.

Numerous iterations of RoboCop after 1987 exist outside of comics: two film sequels, a reboot, and multiple television series, none of which benefited from Verhoeven’s black humor or the push into the grotesque he gives eighties action-violence. Even a couple of the non-comics spin-offs have a notable sequential connection: Frank Miller. Coming off the success of The Dark Knight Returns (1986), Miller turned to Hollywood, with mixed results. Although he received a story and a co-screenwriting credit for RoboCop 2 (1990), the final film is far afield from Miller’s vision for the sequel. Miller returned to work on RoboCop 3 (1993), again receiving a story and a co-screenwriting credit, with the finished movie again disappointing him. “Don’t be the writer,” Miller later said of the experience. “The director’s got the power. The screenplay is a fire hydrant, and there’s a row of dogs around the block waiting for it.”

The experience may have slowed Miller’s cinematic rise, but it did not mean a break with the RoboCop character. Before the release of the third film, Miller scripted perhaps RoboCop’s best-known comics appearance, the RoboCop Versus the Terminator mini-series (Dark Horse, 1992). At this stage, Miller maintained much of his deftness as a comics writer. He neatly combined the two franchises through the premise that RoboCop’s merger of human and machine supplied the self-awareness necessary for the eventual robot takeover of the Terminator films. (At first, the story’s Terminator machines seek not to destroy RoboCop but to defend him from a time-traveling revolutionary.) Miller also writes for his artist, Walter Simonson, a heavy hitter in his own right.

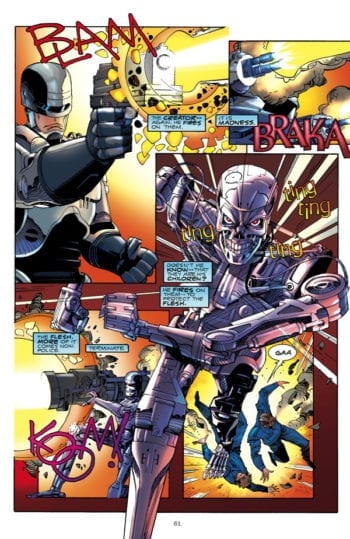

RoboCop Versus the Terminator has an endearing spirit of excess, with Miller conceiving, and Simonson rendering scenarios that would have broken the budget and effects technology of the era’s biggest films. There’s an outer space Skynet armada, a fleet of airborne RoboCops, and a battle scene resembling a robotic Ragnarok, with Miller and Simonson seizing the opportunity to tell an action story on the largest possible scale. Other standout images include a battle-damaged RoboCop holding up a severed Terminator head, an animal-like Terminator holding up a severed RoboCop head, RoboCop helmets lowered assembly-line style onto Terminator heads . . . Simonson lends them all characteristic weight and intensity, although he’s somewhat at odds with technology himself here.

RoboCop Versus the Terminator has an endearing spirit of excess, with Miller conceiving, and Simonson rendering scenarios that would have broken the budget and effects technology of the era’s biggest films. There’s an outer space Skynet armada, a fleet of airborne RoboCops, and a battle scene resembling a robotic Ragnarok, with Miller and Simonson seizing the opportunity to tell an action story on the largest possible scale. Other standout images include a battle-damaged RoboCop holding up a severed Terminator head, an animal-like Terminator holding up a severed RoboCop head, RoboCop helmets lowered assembly-line style onto Terminator heads . . . Simonson lends them all characteristic weight and intensity, although he’s somewhat at odds with technology himself here.

RoboCop Versus the Terminator came at a transitional stage for genre floppies, and Steve Oliff’s very 1992 computer coloring doesn’t always suit the linework. Even so, Simonson’s never less than a match for the mini-series’ scope. It is about as a satisfying as a RoboCop story can be without privileging humor. In other words, a reader’s mileage will vary.

Whatever the source of Miller’s frustration with his collaborators on the second and third RoboCop films, it was not his devotion to Paul Verhoeven’s tone in the first. RoboCop Versus the Terminator contains a few solid throwaway gags—every passer-by on the street is armed; an ED-209 unit attempts to direct traffic in a junkyard—but Miller is not an ironist in the manner of Verhoeven. Even his extravagant robot-warfare crossover treats the pathos of RoboCop more earnestly than the first film. Take this series of lines, typical of the first issue:

Rain falls, driving the humans to seek shelter. Striking his helmet, his chest. He listens to it. It seems so far away. Far away as a woman’s touch. Far away as everything—except the call of duty.

This is a comic that, despite its excesses, invites readers to take its hero’s suspension between human and machine quite seriously. The prose that results, though purple, at least pairs with the story’s Terminator dogs and exploding spacecraft. It’s also an example of the problems the RoboCop character poses to its adaptors. The 1987 film is both an origin story and the end of a story. Murphy’s transformation into a robotic cop threatens to override his humanity, but after defeating his enemies, he achieves a kind of congruence, even reclaiming his human name. Miller’s story—like most subsequent RoboCop stories—depends on reintroducing Murphy’s displacement, on the partial erasure of its source material.

Miller’s selective consultation of the original film manifests in other ways too. RoboCop Versus the Terminator’s principal anti-Skynet revolutionary must whip off her clothes before traveling back in time; she arrives in RoboCop’s Detroit prone and nude in front of a taxicab. It’s a piece of cheesecake that’s rare in Simonson’s body of work—not quite so rare for Miller—but it’s also a departure from Verhoeven’s film, which has in the notorious Bixby Snyder (the “I’d by that for a dollar” guy) a leering creep who revels in the commoditization of sexuality.

Figures like Snyder make it tempting to measure any RoboCop spin-off by its level of anti-capitalist bile. Verhoeven, Neumeier, and Miner envision a world in which unchecked free enterprise has hastened the decay of society. Smiling grotesques dominate TV, sharks and sycophants populate boardrooms, and whenever violence breaks out, Verhoeven depicts it with an ethic of excess distinct from Miller’s. The shooting of Murphy, for instance, plays like a burlesque of standard blood-squib gun-downs, as if Verhoeven—in his second English-language film after leaving the Netherlands for the US—means to confirm or even challenge American appetites for this sort of carnage.

Violence—of an industrial variety—was a feature of Verhoeven’s formative years, with World War II bombings sometimes disrupting his childhood in the Hague. The manner in which his film approaches human carnage is still more remarkable for that. There’s a kind of clowning at work—sometimes outright slapstick, sometimes an embrace of violence that lasts long enough to provoke discomfort. And so it’s tempting also to take a work like RoboCop Versus the Terminator, which is considerably less ambivalent, as a betrayal of the 1987 film. Of course, the ease with which RoboCop Versus the Terminator distances itself from the first movie’s politics might suggest flaws in Verhoeven’s approach too.

In The Art of Cruelty, Maggie Nelson writes, “I believe that the obsessive contemplation of our inhumanities can end up convincing us of the inevitability of our badness,” and later, quoting Walter Benjamin, identifies the risk of floating into “an alienation that has reached such a degree that [humankind] can experience its own destruction as aesthetic pleasure of the first order.” An argument like this—Nelson’s whole book, really—is worth considering for anyone who wants to examine further the meanings of scenes like Murphy’s near-execution, and especially for a viewer who might take the scene’s radical effects for granted. It’s not a given that Verhoeven’s choices in RoboCop benefit viewers. Even a fan of the director’s work might simplify matters too much by framing his film as the great Trojan horse of eighties blockbusters.

Most of the character’s comics appearances seem to confirm that the film’s critiques often failed to reach people. But there’s nonetheless a rare tension in the film that’s still compelling more than thirty years later, with Verhoeven simultaneously embracing and attacking the very systems that provide for a mass-marked, multi-million-dollar action film. The presence of a similar tension is one metric we can count on in deciding how well a comic, or any spin-off, follows this first movie.

* * *

Dark Horse would publish a few more mini-series during the mid-nineties, Prime Suspect, Mortal Coils, and Roulette, before RoboCop’s comics appearances receded along with the franchise’s larger cultural cachet. There’s not much tension in these stories. Mortal Coils (1993), from writer Steven Grant and penciller Nick Gnazzo, introduces a couple of promising premises but doesn’t make much out of either one. Acting as a federal marshal, RoboCop arrives in snowy Colorado, looking for a black-hatted, Danzig-mulleted criminal named Coffin. Coffin’s aging benefactor, Mr. Agincourt, sees an opportunity in the conflict: to achieve immortality by having his brain placed in a RoboCop body. Mortal Coils never completely commits to being either a winter western or an EC-style reversal-of-fortune horror story. Although Agincourt gets what he wants, after a fashion, he’s only able to inhabit an ED-209, which quickly makes him wish for his own death. It’s a turn too awkwardly paced to be much fun.

Dark Horse would publish a few more mini-series during the mid-nineties, Prime Suspect, Mortal Coils, and Roulette, before RoboCop’s comics appearances receded along with the franchise’s larger cultural cachet. There’s not much tension in these stories. Mortal Coils (1993), from writer Steven Grant and penciller Nick Gnazzo, introduces a couple of promising premises but doesn’t make much out of either one. Acting as a federal marshal, RoboCop arrives in snowy Colorado, looking for a black-hatted, Danzig-mulleted criminal named Coffin. Coffin’s aging benefactor, Mr. Agincourt, sees an opportunity in the conflict: to achieve immortality by having his brain placed in a RoboCop body. Mortal Coils never completely commits to being either a winter western or an EC-style reversal-of-fortune horror story. Although Agincourt gets what he wants, after a fashion, he’s only able to inhabit an ED-209, which quickly makes him wish for his own death. It’s a turn too awkwardly paced to be much fun.

The one curiosity of Mortal Coils is Gnazzo. His approach on many pages looks something like Keith Giffen trying out a Sam Kieth impression, functional but not boring. Like the start of a shift, even; Gnazzo’s panels suggest an artist whose best work was still to come. (In actual fact, his comics contributions seem limited to the mid-nineties.) Naturally it’s Grant who stuck around, becoming a steward of the RoboCop franchise at a time when it served as an outlet for professional Frank Miller fandom.

A decade after Dark Horse’s RoboCop comics, Avatar acquired the rights to the character. The publisher also licensed Frank Miller’s original screenplay for RoboCop 2, which Grant then re-scripted for a print mini-series. Frank Miller’s RoboCop (2003) differs greatly from Miller’s depoliticized take on the character in RoboCop Versus the Terminator. Building on a plot point from the original film, the story finds Detroit’s police department on strike, with the members of “Rehabilitation Concepts,” a private security group, acting as strikebreakers and killing with impunity.

RoboCop has continued to patrol the streets—not because he opposes the strike, because he can bear burdens his colleagues can’t—but his programming is on the fritz. When he’s tasked with cleaning out low-income housing for demolition and leaving the buildings’ inhabitants homeless, one of his directives (protect the innocent) interferes with another (uphold the law). With RoboCop faltering, Dr. Margaret Love—a psychologist in the employ of OCP—devises an alternative. We learn that Murphy’s underlying morality has become a liability, and the ideal candidate for the next human-robot hybrid will be a “value-neutral subject.”

In addition to its ideal officer for a corporatized state, Miller’s script also recaptures some of the dark humor of the first film. Newscasters mention the slaughter of Mexican nationals by US satellite cannons and add, with a smile, “As soon as the oil fields stop burning, Texas will be American again.” The broadcast proceeds one panel later with a commercial for “Behemoth Foods,” a company that modifies produce to be larger than people. This world is, like Verhoeven’s, a horrific and stupid place.

In addition to its ideal officer for a corporatized state, Miller’s script also recaptures some of the dark humor of the first film. Newscasters mention the slaughter of Mexican nationals by US satellite cannons and add, with a smile, “As soon as the oil fields stop burning, Texas will be American again.” The broadcast proceeds one panel later with a commercial for “Behemoth Foods,” a company that modifies produce to be larger than people. This world is, like Verhoeven’s, a horrific and stupid place.

And yet Frank Miller’s RoboCop is an Avatar comic as much as anything else. From artist Juan Jose Ryp’s first elaborately rendered sex robot in one of Miller’s mock TV ads, the distance between the story’s exploitation elements and the impulse to satirize them quickly begins to contract. Ryp might be called the Geof Darrow of sleaze: from the grit of a floor tile to the suds of an exploding beer bottle to the pockmarked skin of a criminal, Ryp endows nearly everything he draws with a striking level of detail. There’s an elaborate car crash in issue one, for instance, and although a later test-run for a replacement RoboCop plays almost exactly like an ED-209 scene from Verhoeven’s film (complete with an onlooker’s accidental execution), the visual hyperbole of Ryp’s linework makes for a compelling spectacle.

The depiction of violence is nothing like Verhoeven’s, without the same complex power to invite and repel. The mini-series makes more aesthetic (and commercial) sense as a companion piece to something like Hard Boiled, as an appeal to Miller completists. Although this mercenary logic still gives way to some strong pages, Ryp’s action sequences also sometimes lack coherence. It’s difficult to discern who’s at fault: the artist, Miller, or Grant. But what compromises the story further is the lack of irony behind its lowest-common-denominator approach.

Ryp draws RoboCop’s adversary Margaret Love in an outdated, unreconstructed nineties-bad-girl-comics style, with extreme cleavage and skintight party dresses. Whenever Love is trying to dehumanize RoboCop on a plot level, urging him to lose touch with his inner person, this kind of lazy objectification creates dissonance across the panels. Meanwhile, RoboCop’s partner Lewis—a punchy foil for Murphy in the film—can’t go one page without getting her clothes torn to ribbons, as if a hypersexual makeover was a prerequisite for her inclusion.

Ryp draws RoboCop’s adversary Margaret Love in an outdated, unreconstructed nineties-bad-girl-comics style, with extreme cleavage and skintight party dresses. Whenever Love is trying to dehumanize RoboCop on a plot level, urging him to lose touch with his inner person, this kind of lazy objectification creates dissonance across the panels. Meanwhile, RoboCop’s partner Lewis—a punchy foil for Murphy in the film—can’t go one page without getting her clothes torn to ribbons, as if a hypersexual makeover was a prerequisite for her inclusion.

These are obvious critiques of what we could justifiably call goofy junk, but when the junk in question foregrounds at story level the act of recognizing a person’s humanity, its lack of conviction still stands out. Also worth noting: only Miller’s name is on the covers of these comics. Whatever the quality of Grant and Ryp’s efforts, a gesture like this still downplays the work involved, and it no doubt misled numerous readers upon the comics’ release. In a more or less holistic way, this is not a project that walks the walk.

It is difficult to recommend Frank Miller’s RoboCop—more like a reader might approach it with caution and encounter a few pleasant surprises. Certainly these comics aren’t better than the original film. But they do present again the question of whether a work’s critique means anything or does anything when conveyed through this kind of enterprise. In a way, Frank Miller’s RoboCop even intensifies the question. The stakes are lower with the release of an Avatar comic than with a Hollywood film, but the shamelessness with which Avatar and these comics’ creators operate creates its own friction with the story’s anti-authoritarian politics. If the people involved were looking to see how far they could push a trash aesthetic and still maintain a kind of credible social comment, well, they found the line and tripped over it.

* * *

After adapting Miller’s screenplay, Steven Grant scripted a pair of RoboCop one-shots for Avatar, Killing Machine and Wild Child, before the RoboCop license made its way to Dynamite Entertainment. Dynamite published three mini-series in total, written by Rob Williams and drawn first by Fabiano Neves (RoboCop: Revolution, 2010), then P.J. Holden (Terminator/RoboCop: Kill Human, 2011), and finally Unai Dezarate (RoboCop: Road Trip, 2011). The most notable, almost by default, is Kill Human. The series invites comparisons to the Miller-Simonson double act of RoboCop Versus the Terminator, with doesn’t greatly benefit Williams and Holden, but the team still deserves credit for upsetting anyone who might treat a crossover between two massive entertainment properties as a sacred cow. (There are a dozen different iterations of Alien vs. Predator, someone must have thought, so why not?)

Kill Human is not a sequel to that earlier RoboCop Versus the Terminator mini-series and shares no continuity with it, though it does play with readers’ awareness of the previous crossover. The story begins in the same manner as Miller and Simonson’s, with most of humankind eradicated by Terminator robots and a human revolutionary on the run. In RoboCop Versus the Terminator, the character travels back through time, intent on destroying RoboCop and preventing Skynet’s takeover of Earth. In Kill Human, the revolutionary activates a long-dormant RoboCop and they form a brief alliance—before Skynet takes control of him and uses him to kill the freedom fighter, ending humanity in the process. Distraught, RoboCop travels back in time himself, committed to stopping Skynet’s rise (unrelated to OCP in this crossover) before it starts. His mission plants him in the middle of Terminator 2: Judgment Day.

Kill Human is not a sequel to that earlier RoboCop Versus the Terminator mini-series and shares no continuity with it, though it does play with readers’ awareness of the previous crossover. The story begins in the same manner as Miller and Simonson’s, with most of humankind eradicated by Terminator robots and a human revolutionary on the run. In RoboCop Versus the Terminator, the character travels back through time, intent on destroying RoboCop and preventing Skynet’s takeover of Earth. In Kill Human, the revolutionary activates a long-dormant RoboCop and they form a brief alliance—before Skynet takes control of him and uses him to kill the freedom fighter, ending humanity in the process. Distraught, RoboCop travels back in time himself, committed to stopping Skynet’s rise (unrelated to OCP in this crossover) before it starts. His mission plants him in the middle of Terminator 2: Judgment Day.

In some ways, these are not very good comics. Holden is an inelegant inker of his own pencils, leading to figures that are blocky and yet rubbery. Rainer Petter’s coloring doesn’t help; it’s the kind of gradient-intensive genre-floppy coloring that gives every object a metallic sheen, whether the item’s metal or not. No one action sequence stands out either, which by some measures is enough for a failing grade. (When RoboCop gathers an army’s worth of ED units to combat the T-1000, for example, it plays like a diminished version of Walt Simonson’s infinity-scale robot warfare.) It may be, then, that reading Kill Human after a few dozen issues of other RoboCop comics leads a person to appreciate out of proportion the ways in which the mini-series outdoes the works surrounding it. Nevertheless, there’s fun to be had here—possibly for the casual reader but at least for the critic suffering from a kind of RoboCop-comic-induced Stockholm syndrome.

Kill Human plays with the RoboCop character’s inner divide in a novel fashion. Murphy’s guilt over killing the future’s last human leads to a machine-like focus, so much so that he doesn’t really care whether John Connor, Sarah Connor, and their ally, the T-800, become collateral damage in his crusade against Skynet. RoboCop’s own actions—his willingness to endanger the Connors—become the primary threat to his own humanity. RoboCop’s strategy is also charmingly convoluted in places. Readers learn that he actually traveled back five years before the events of Terminator 2, for the sake of founding OCP himself and creating his fleet of anti-Terminator ED-209s. Although the reveal underwhelms on a visual level, the plot’s determination to account for stuff like this, to convey through painstaking story logic how RoboCop might arrive at an army of EDs, makes for a fine balance between smart and dumb.

Coming in Part Two: