The finest combination of words and pictures I have seen in some time is Ivana Filipovich’s Where have you been? (Toxic Ink, 2022). Filipovich is both a skilled artist and a talented writer. Her work rewards the eye and enriches the mind. You will not be sorry.

Her comics career comes, intriguingly, in two parts, nearly 20 years and 5,000 miles apart.

Filipovich was born in 1965 in Jagodina, a town of 50,000, whose name loosely translates as “Strawberry Fields”, in what is now Serbia. Her mother taught high school geography and her father served as an official in the ruling Communist Party of Josip Broz Tito. In a relatively classless society, Filipovich’s family was “upper class”, meaning she might have one more pair of jeans or better sneakers than her classmates. Pre-breakup Yugoslavia was an open society compared to the Eastern Bloc of communist countries. There was a lively arts scene. People could travel abroad and were exposed at home to the best of culture: Tolstoy and Kafka, Bunuel and Tarkovsky, BBC dramatizations, American punk and post-punk music. Her taste in comics ran toward Hugo Pratt, Sergio Toppi, and José Muñoz & Carlos Sampayo.

While studying for an MS in Architecture at the University of Belgrade, Filipovich began working, at age 22, as an architect, city planner, and illustrator. Her illustrations and comics were exhibited in Serbia, Greece, Macedonia, Slovenia, and throughout western Europe. She became the first cartoonist to be published in a Serbian literary magazine, the first Serbian female cartoonist to be published abroad, and “most likely” the first cartoonist in Serbia–and “maybe” all of the former Yugoslavia–with an LBGTQ+ lead character. (Jagodina, she says, was known as Serbia’s “queer capital.”) In 1995, KvadART magazine named her one of Yugoslavia’s most influential artists.

But by 1999, following the country’s disintegration, war had made life in Serbia precarious. Though both her parents, her younger sister, and she worked, the family often could not afford food, and Filipovich decided to leave. But since much of the world considered Serbia an aggressor nation, even skilled immigrants like herself had limited options. Australia, New Zealand, and Canada needed professionals though, and she selected the latter.

Filipovich had already become frustrated with architecture because only those at the top had the opportunity for creative work. (Plus, Canada required an adjustment for Europeans accustomed to working on family dwellings of brick and concrete, not wood.) So not long after her arrival, she decided to shift her career to web design. “After 10 years being hungry,” she says, “I thought, ‘Screw this. I don’t want to be hungry again.’” She put art aside. “I worked. I traveled. I shopped. I enjoyed myself.”

After being hired as a designer at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver in 2002, she rose to become a unit manager, executive producer, and art director. Her educational media team’s work garnered awards from the UN, UNESCO, and the Advertising and Design Club of Canada. At present, she is SFU’s analytics specialist for communications and marketing.

Since returning to comics in 2017/18, Filipovich has been published in a Slovenian philosophy magazine, a Serbian literary magazine, and anthologies in Serbia and Sweden. Her work has been exhibited in Canada, Serbia, Slovenia, Croatia, and France. She lives outside Vancouver with her husband, a fine artist, and their cat. Her sister moved nearby in 2001. “She came for a visit but fell in love with a friend of mine and is now happily married... [with] two sons.”

Whyb?, a collection of black-and-white stories, is Filipovich’s first book. Ten of the stories were created between 1995 and 2000, and six between 2017 and 2020. (The two sections are separated by portraits, drawn in 2018, of 13 female artists Filipovich admires, including Elaine de Kooning, Georgia O'Keeffe, Julia Cameron, Joy Williams, and Vivienne Westwood.) The shortest story runs for one page, though two of the longer ones, “Maurice in the Middle” (2020) and “My Neighbourhood” (1995, 1999), consist of linked one-pagers. The longest, “What Does Fear Have to Do With It?” (30 pages, 1999), has been developed into a graphic novel which will be published this September by Conundrum Press.

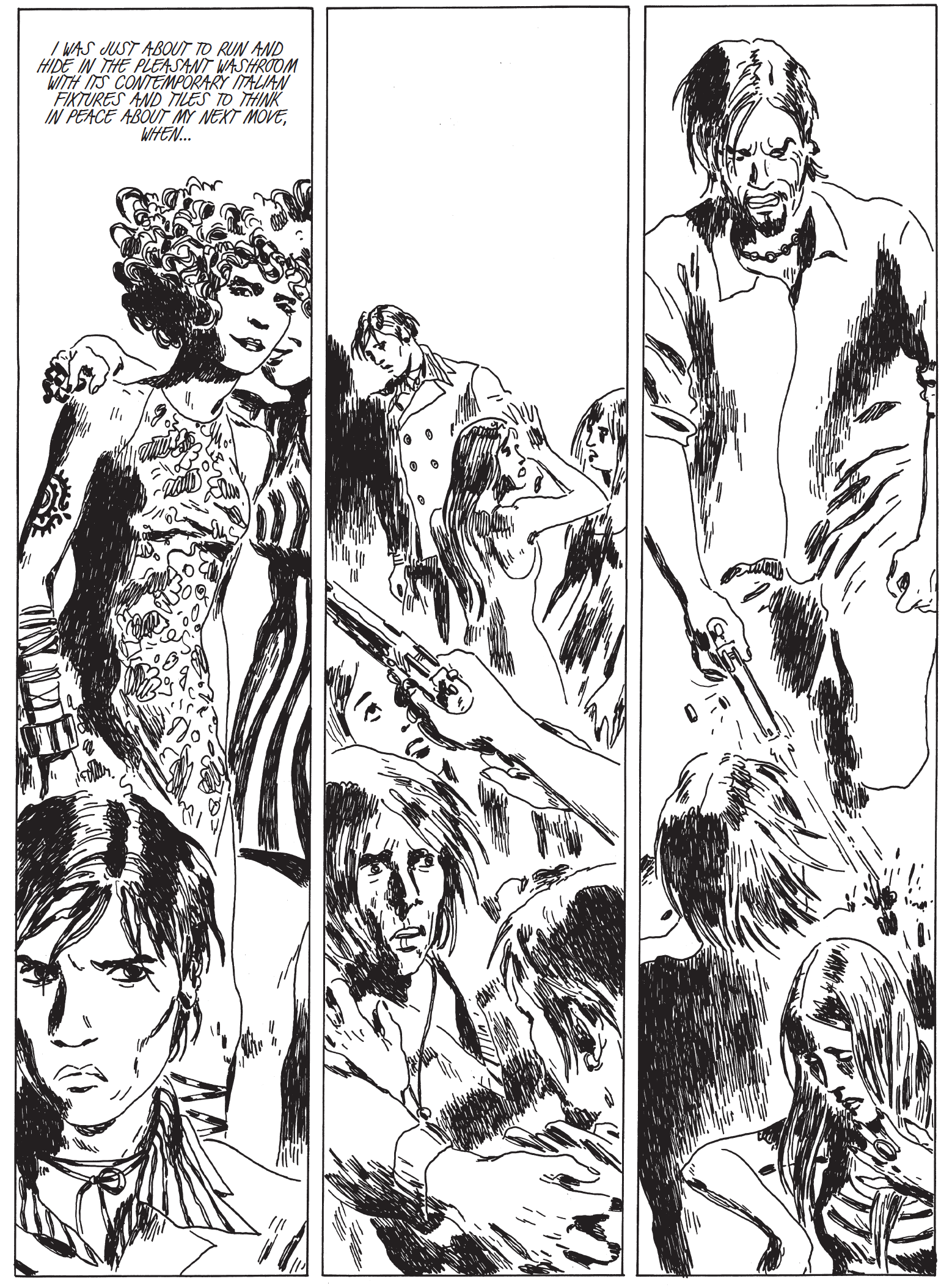

In the stories from her first period, while there are diversions into dream, fantasy, sci-fi, and one multi-character romp set in and about a turn-of-the 20th century opera house, most center in the Belgrade club scene of the 1990s - or concern people who could find themselves in a club later in the day, after completing the activities Filipovich has depicted. “Fear” is one of these. (The “Zu-Zu” is its club.) Its featured players are Eva, Mia, Max, Martin, and Sandra. All are 20- (or early 30-)something. All except Max, a loan shark, are unemployed. Scenes occur in and outside the Zu-Zu, in apartments of those who frequent it, on the balcony of one of these apartments, in a boutique. There is a knife fight, fist fights (man-on-man, woman-on-woman, man-on-woman). A Dolce & Gabbana coat figures prominently in the storyline. The proposition is promulgated that almost all of life is performance art.

Max and Martin are friends. Eva has betrayed Max with Martin. Sandra has a relationship with Martin and with Mia, and has an eye on Eva. The story confuses. Not only are characters similarly-named, they are not always rendered so as to be easily distinguishable. Close attention to dress and hairstyle may not be enough. (“Fear” is not a Russian novel where keeping a list of characters handy is necessary, but taking notes can help.) To add to the confusion, time and place can shift abruptly, from panel to panel or with the flip of a page. The vibe is of jealousy, betrayal, and people with empty lives hurting other people with empty lives, with no one at story’s end more damaged–or headed for a better future–than they had been before the story began.

It is a tolerant, if critical, look. It suggests that, given this world–young people, Belgrade, the ‘90s–what do you expect? What else is possible? Cynicism and make-the-best-of-it resignation abound. If nothing else is of value, why not a designer coat?

With “My Neighborhood”, Filipov’s final work of this period, things change. In three-to six-panel vignettes, she penetrates and probes the lives of residents in (or near) a lower-middle (or upper-lower) class apartment building. Mental illness, prostitution, infidelity, child abuse, and aberrant sexuality cross her page, but not for shock value or sensationalism. Meanness and tragedy are present, but also humor and poignancy. She presents characters to be weighed, moved by, pondered, and, perhaps, respected.

They live in a country cursed with chaos. Basic services, from the mundane to the horrific, are denied them. A fellow is trapped for hours in an elevator. A man, who died while off fishing to feed his family, has his body dumped outside the building’s front door. But both episodes conclude with a page-wide panel in which other residents convene to complain, socialize, and drink.

Whether for joy or oblivion is unclear.

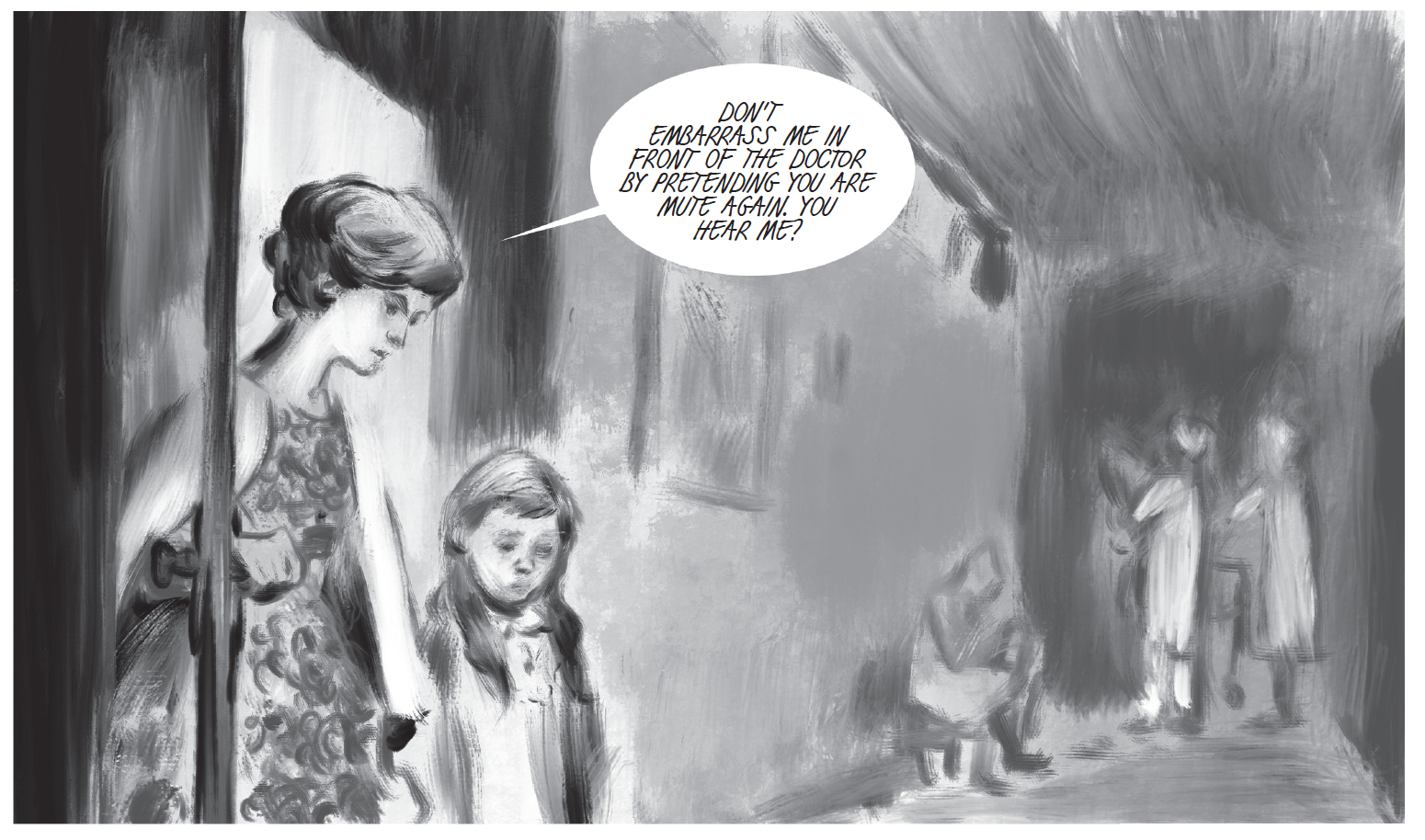

With Filipovich’s return to comics, her interest in and attention to people seemed to deepen and broaden. The type of person she portrayed and the situations in which she engaged them expanded, but she remained respectful and empathetic. Her narratives are understated and her judgments well-considered.

A young woman reflects with muted–but all the more effective–affect upon a former boyfriend’s destruction by a dictatorship’s brutality. A Haitian adrift in Vancouver finds solace in memory. Another young woman explores her homeland’s bloody ancient past to comment on its bloody present. A middle-aged woman is crushed–literally diminishing panel-by-panel–by recalling a lost potential chance for love. A kindly doctor uncovers a little girl’s secret. In the concluding story, a tour de force of three equally-dimensioned panels per page, a separate conversation occurs between an unnamed, unseen woman on the left of each panel, and an unnamed, unseen man on the right, with a cat between them, always visible and always indifferent. The man and woman bicker, joke, discuss literature and politics.

Life flows.

Filipovich’s visuals are secondary to her words. Her backgrounds are rarely detailed. In the early stories, when she worked with Rapidograph, pen, and brush, they are often blank (white) or opaque (black). In her later period, where the art is primarily digital, they tend toward swatches of grey. (The shift, I think, may represent a shift in her views on the nature of existence. Things may no longer be as clear-cut as they once seemed.)

Filipovich’s emphasis throughout is on her characters. Their garments and coiffures, especially in the earlier stories, receive her keen attention. (In the later stories–again, perhaps a statement of philosophy–they become sketchier as though to blend people into a commonality.) Throughout, her emphasis is on the emotions that cross faces and register in eyes as time and events impact them. Her visuals play like a pianist accompanying a jazz vocalist. They do not command the stage but emphasize and augment what is more central. Her goal, she says, is the “accurate depiction of psychological states of characters, often missing from comics and graphic novels.”

The literary quality of Filipovich’s book is striking.

So is its maturity. It is rare in my experience to open a “comic” and meet such a fully-formed and rounded adult creative consciousness, one neither confined to the autobiographical (though much of what she writes derives from the personally experienced), nor blinkered by the political (though politics is often a weighty influence), nor eroded to a narrow whrill and grating nub by bitterness and cynicism. (Maybe I don’t read enough comics. Maybe my previous writings influences the ones I naturally attract.) Filipovich stands back, looks upon the observable with interest, bemusement, and sympathy. She recognizes that life can be hard without being pointless. She understands succor can be found in the darkest shadows.

Her major influence, she told me, is Chekhov. She rereads his collected stories every year, “Mining everything, the realism, the humor, the level of human understanding, the mastery of character and conversation and situation. He gives you just enough to form your own conclusions. I want readers to have their minds open and have their own experience, even if its different than what I intended.”

Or as Chekhov wrote to the publisher Aleksey Suvorin, it is not “the solving of the question... [but] the correct putting of the question... which is obligatory upon the artist.”

Answering them is each of our responsibility. And if enough right answers can be found, a course-correction may be reached.

Isn’t it nice to think so?

* * *

Subsequent to this piece's submission, but prior to its publication, Where have you been? received the Doug Wright Award for best small press book at the Toronto Comics Arts Festival. Our reviewers are nothing if not prescient.