In this sample from a feature article in The Comics Journal #309, Helen Chazan reconsiders Kim Thompson’s landmark 1999 essay “A Modest Proposal: More Crap is What We Need” by way of Brian K. Vaughan’s and Fiona Staples’ enormously popular Image SF series Saga. All excerpts from Saga in this piece were drawn and colored by Fiona Staples, written by Brian K. Vaughan and lettered by Fonografiks.

When people in Saga have sex, they often cum, but as a reader I found it hard to say what their orgasms felt like, if they felt them at all. In space, it seems, no one can hear the female orgasm. Sexual violence and sexual trauma are handled even more awkwardly - a plot line involving the rescue of a child sex slave in the fourth issue jars with the montage of liberated play parties that introduce the brothel planet of Sextillion. That it’s difficult to truly address the trauma and violence of child sex abuse in the pages of a mass audience space opera is understandable, but just as Vaughan et al. have little to say about sex other than that it is fine and maybe funny, they have little to say about rape other than that it is really bad. With these themes jammed together the shallow callousness of this messaging is hard to ignore. When it comes to depicting something like sexual experiences, be they joyous or traumatic, one has to speak a little more honestly than slogans of allyship. Unfortunately, that’s all that Vaughan and Staples have to share about just about anything, even about the vast mysteries of space and the wonders of imaginary worlds. It’s perfunctory.

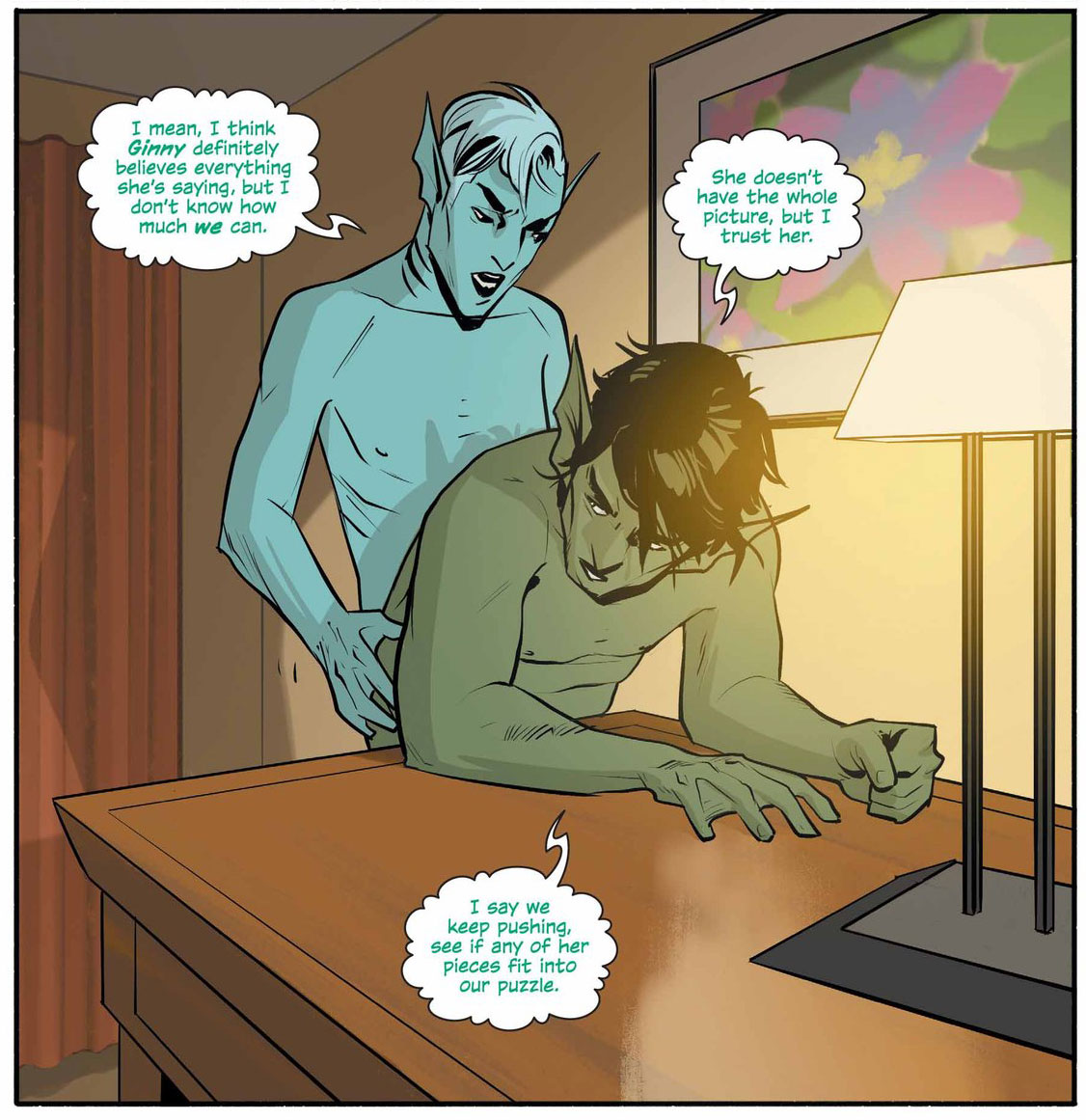

Bodies themselves are also perfunctory in Saga. Alien people tend to be a standard set of human male and female forms with a default, slim musculature and the addition of one or two distinct elaborations - horns, wings, elf ears, more or less eyes, an odd shade of skin, a TV set for a head. Occasionally, mildly compelling oddities appear like an anthropomorphic seal in overalls, two women who are literally all legs, a spider with boobs, or an ogre with huge testicles, but these are mostly sight gags and tertiary characters whose appearance is meant to shock and amuse the reader - the universe of Saga can be carved up neatly into what is easy to cosplay and what isn’t. Outfits trend towards the American Apparel knitwear basics end of the style spectrum, with a dash of Spirit Halloween costume and the odd military uniform. Minimal, hardly even aesthetic fast fashion rules this galaxy. Given that comics have infinite potential for depiction that has indeed been plumbed for possibility by countless illustrators, isn’t this a tad boring? Like the “allegories” pasted together to resemble a plot, Saga’s horizons present a world reminiscent of this one through a frustrating, drab lens, with all the magic of an Apple default screensaver.

This is indicative of Saga’s structure and nature as pop fiction. Throughout the work, many important messages are strung about as pithy punctuation marks without much consideration to their meaning. No central fixation or preoccupation dominates the work consistently. The comic can’t imagine a better future, a worse future or a compellingly different society, because that might involve constructing an allegory that is complicated, or that could be misread or one that might exist only for itself, which would leave audiences with something to ponder and discuss, or simply enjoy, that can’t be put on a T-shirt or in a 200-word viral article by an unpaid intern. The morals break apart like Play-Doh if you tear at them long enough and leave nothing of value except for the liberal assumptions of what sounds progressive enough to work.

The experience of reading Saga is, for better or worse, a lot like scrolling a social media timeline. Traveling down an endless corridor of snarky snippets and pointy retorts, accompanied by Digipaint renderings of science fiction folks with their titties and nipples happily freed, the occasional monster and galaxy, peppered with stark anti-war messages and pro-sex-worker feminist solidarity delivered sharply and with no context. Get a little riled up; get a little entertained; engage, chill, then put down the comic, or the phone or the comic that’s read on the phone: then forget about it. Time wasted, but well-spent. Not needed for anything better. And some of it was very good.

Saga is, in many ways, exemplary crap. It is artfully executed; it is exactly what it says it is on the tin but provides enough flavor for the open-minded reader to provide the extra meaning they might need. What is unfortunate about Saga is that it is outstanding, and it should not be. In the year of our lord 2022, when I am writing this, I should not be impressed to read a popular comic that is coherent, accessible, entertaining enough to be absorbing and just barely interesting enough to solicit an actual conversation with fellow readers. It should not be extraordinary to read a comic for adults in which sex and violence are major elements of the story, and it should not be rare for a work of popular culture to be explicitly anti-war even in a vague way. In a better creative moment this comic would still be a good bit better than average, but right now, it’s exceptional. It demands celebration. This is a sad and sorry state.

And so, we arrive at this larger cultural moment where Big Mouse is actively shuttering opportunities for any manner of artistic expression save the most cynically corporatist. In this world where the Intellectual is made Property, prestige crap abounds, the little pieces of crap left to get squished out, lauded as singular because there is so little left - the Game of Throneses, the Lady Birds, the John Wickses, the Euphorias. Beneath this strata, real pulp has gone underground, and this too is a shame - there will never be another Richard Corben who traverses counterculture and mass culture freely, nor another Jeffrey Catherine Jones bringing the strange and intimate to the covers of hackwork. Most people will never see the great trash, and the good crap stakes out a lonely, cold outpost. Kim Thompson’s picture of crap was from a time when crap meant reruns of Columbo and Kolchak. Nothing on television today is nearly as profound or beautiful as reruns of Columbo and Kolchak.

Saga is but one lonesome piece of isolated crap. Will any reader of Saga read more comics? Maybe they will if they are friends with someone like the author of this essay. Otherwise, they may read another Brian K. Vaughan comic, or another Image hit. They’ll do this for a while, get bored, drop it. The likes of Paper Girls and Sex Criminals roll off the mind like so many streaming TV serials. They even get adapted into so many streaming TV serials, but unlike a Netflix series, they often lack the reach and hyper-moneyed apparatus to be forcibly crammed down audiences’ mind holes. Saga will be a comic many people have read, and liked, but not enough to take them on the kinds of wonderful and personal reading journeys that lets one declare it their favorite comic. Does that mean Saga didn’t do enough? Aren’t there other crap comics out there good enough for readers? Are publishers to blame? Critics? Retailers? The Direct Market? The boogeyman? Maybe everything in comics is wrong and only the brave readers of The Comics Journal can fix the course. Maybe it’s time to see how, nearly a quarter century later, culture answered Thompson’s demand: crap was, and is, indeed what comics needed all along, and crap has made comics better, but the market today is not built for crap but instead for industrial waste, a facsimile of proper rubbish from bygone days. Comics like Saga laid the groundwork for today’s industrial waste, too embarrassed by the scent of shit to see its value. Comics like Saga have themselves become antiquated; Image hasn’t had a new series hit at that scale since the halcyon days of 2011–2014, with titles’ sales consistently dwindling after their first issue - Image’s biggest seller in recent years was Saga’s return from hiatus. Saga did not do for Image what Sandman did for Vertigo. No imprint with a recognizable impression of quality was left in Saga’s wake. Maybe there is something to the nature of Saga itself that produces an indifference to encountering any other crap of its ilk. After all, Saga is at its core a comic that reminds audiences that it is very important to keep reading Saga. No other message is felt so profoundly among its pages.

* * *

Read the full essay in The Comics Journal #309.