In her debut graphic novel Est-ce qu’un artiste peut être heureux? ("Can an Artist Be Happy?"; Revue Zinc, 2022, French-language only), multi-disciplinary artist Arizona O’Neill illustrated 12 interviews she conducted with Québécois artists. Featuring dialogues with the cartoonists Julie Doucet, Pascal Girard, Mirion Malle and Walter Scott, along with musicians and artists like Hubert Lenoir, Klô Pelgag, Laurence Philomene, MissMe and others, the book surveyed the ways that a person’s conception of happiness shaped their artistic outlook. The responses from the assembled interview subjects are astoundingly frank discussions of success and failure, the changing cultural landscape of the city of Montreal, and the means to effect the “good life”. Taken in total, the vignettes offer persevering and dignified understandings of what it means to be a jobbing artist working in the 21st century.

Formerly a bookseller at Drawn & Quarterly, and now the resident mural artist of the publisher’s Mile End retail store location, O’Neill is also heavily active as a video artist. She has directed several music videos for the singer-songwriter Patrick Watson, and produces video essays for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation on topics ranging from the evolution of feminine hygiene products to the disappearance of seedy street signage in the urban landscape of Montreal. She collaborates frequently with her mother, the novelist Heather O’Neill, and together they run the popular Instagram book and comics review account oneillreads.

I corresponded with O'Neill to discuss the tormenting and elusive nature of happiness, the centrality of emotion in most art-making, and the growing irrelevance of review culture.

-Jean Marc Ah-Sen

JEAN MARC AH-SEN: Your book serves as a qualification on conventional understandings of happiness; in many ways, it asks readers to reassess their own conceptions of work, rest and productivity. Did you anticipate that your respondents would have ambivalent or in some cases adversarial relationships to these subjects, given their various vocations? Mirion Malle’s definition of happiness as the “power to feel a full range of emotions, not necessarily just joy,” stands out in particular to me.

ARIZONA O'NEILL: Before starting the interviews, I knew everyone’s answers would be different. Artists are able to articulate emotions well because they mostly work in a corner of a room analyzing them. As Paul Cézanne famously said, “A work of art which did not begin in emotion is not art.”

I was expecting more pessimistic answers, but every single artist had an uplifting view on happiness. Their unique takes fit in very nicely with their art practice. For example, [Malle] tackles depression in her work. Her characters enter that scary numb emotional space that some of us know too well, and her definition of happiness as the “power to feel a full range of emotions” is in response to that.

Another respondent in the book, the poet and translator Daphné B, espouses the belief that happiness is unattainable, and “made of frugality, of moments.” Julie Doucet echoes this sentiment to a degree when she calls happiness “bread crumbs that I drop around me.” Is this how you have come to understand happiness as well? Did the project arise out of a search for your own version of a complimentary, made-to-measure happiness?

I think the elusive nature of happiness is something that torments everyone. I have always believed that happiness was a social construct. It is an unobtainable goal that is dangled in front of us to keep us on track. We are led to believe that if you follow the steps of marriage, house, kids, [that] you can find happiness. After writing the book, I understood that being content is better than fleeting happiness. Sustained happiness is impossible - it is a euphoric high that only occurs every so often. But when you forget happiness exists—when you don’t focus on it as the end goal—you can find some form of contentedness.

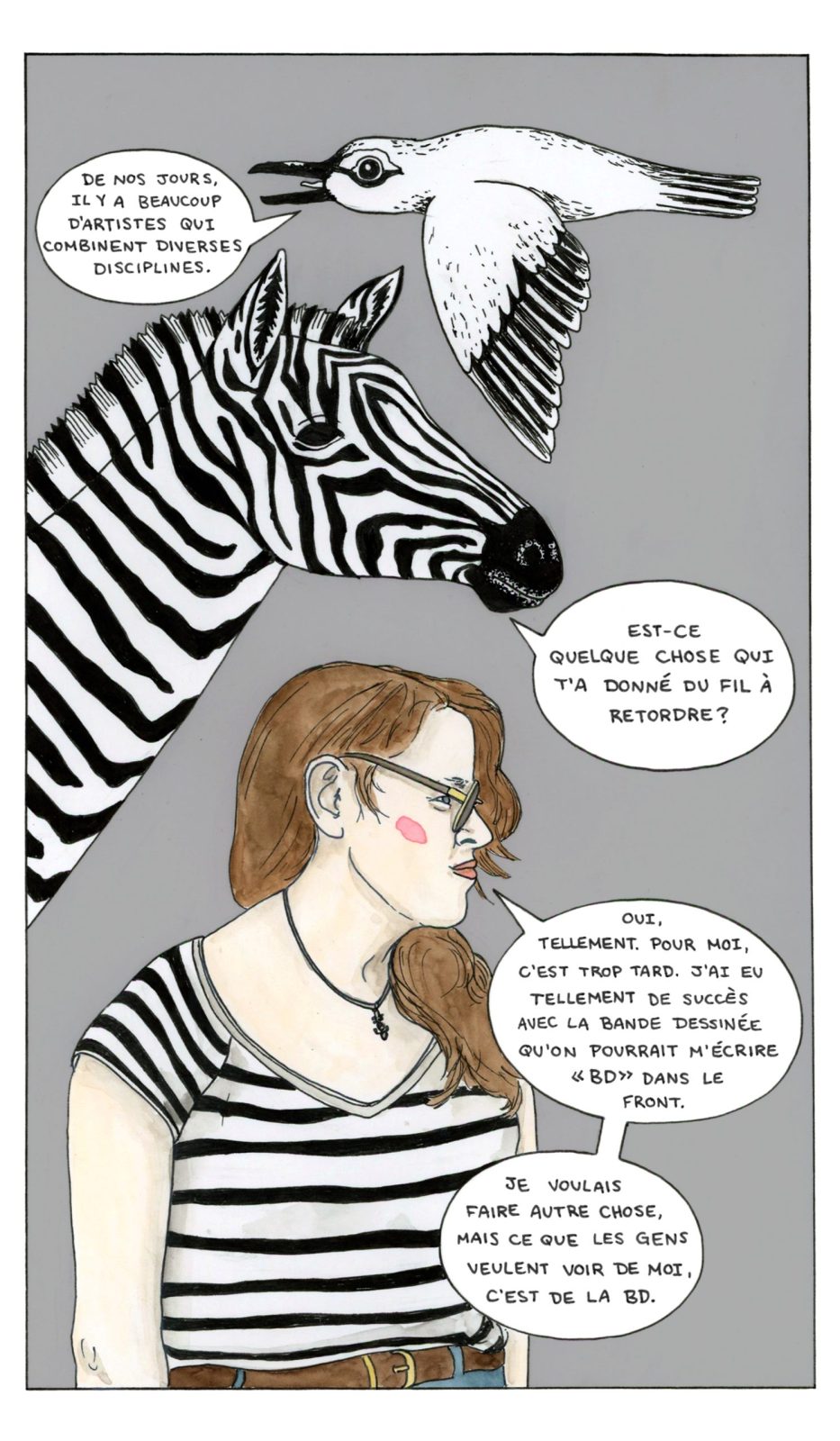

"Many artists these days blend many practices into one."

"Did you find this difficult when you were emerging on the scene?"

"Yes, so much. For me, it's too late. I've had so much success with comics that you could write 'Comics' on my forehead."

"I wanted to do something else, but all people want to see from me is comics."

Can you describe your decision to create a book that was dialogic in nature, abounding in multiple perspectives? Is the work that you seek to create resistant to the idea of the artist as a figure of unchallengeable artistic authority, or was the decision couched in another rationale entirely?

I have always loved works of art that interact with the audience and acknowledge the reader or viewer. Even though the book is a private conversation between two people, I wanted the reader to feel as though they were part of the dialogue as well. There are moments in the book where I break the fourth wall, and my character addresses the reader, and they were the most fun to write.

A recurring theme of the book is the changing cultural landscape of the city of Montreal; your latest CBC video, on the disappearing neon signs of Montreal’s Ste-Catherine Street, touches on this. Does the city still energize your work, or do you think that its economic frustrations are beginning to make it hostile to your ability to make art?

Cities are always evolving and changing, and I do not think this is a bad thing. Most cities put in the work to preserve their history throughout these changes, either with museums, heritage laws, or a simple plaque on a building. But since Montreal has a sleazy history that does not fit the Canadian aesthetic, there is not much effort to publicly display it, and that enrages me. It fuels me to keep including that history in my own work to keep it alive.

How did your interest in comics begin, both as an enthusiast and as a visual artist? Is there something about the comics form that makes it an exceptionally viable medium in which to develop your drawing skills?

I can’t remember a single moment in my life where I didn’t have a comic book in my bag. I had a lot of difficulty reading when I was a kid, as I am dyslexic. School was hard, and comics were my escape from academics. Their scope, visual beauty and tangential storytelling appealed to my neuro-divergent brain. My obsession never stopped, and I now have an amazing graphic novel, classic comic and manga collection at home. I eventually got a job at Drawn & Quarterly’s bookstore, where I worked for five years. It was spending time in a graphic novel bookstore that really pushed me to try it myself.

Compared to other forms, the graphic novel is still a young medium. That is not to say that comics don’t have a rich long history, but that the non-fiction graphic novel format is still fairly new. It is a perfect place to develop a drawing style. We celebrate experimenting with the form because it is still growing and evolving, creating endless possibilities for the genre.

"There is a running gag in the Montreal Queer community that everyone thinks Screamo is based on someone they know."

"Let’s put it to rest: is Screamo based on one person?"

"Haha! No, he is absolutely not based on one person. But if people think that, then I must be doing something right."

"He is based on my own queer anxieties. But it is nice to know that people share those anxieties and see themselves in the character. "

"Do people often ask you if the characters were based on them?"

"Yes, it is often a friend of theirs I have never met. It happens often, and I think it’s interesting."

"I’m a relatable character, ok?"

"What about me?"

What were the texts that were instrumental to your understanding of the scope of the comic book form?

Leanne Shapton's Was She Pretty? [Sarah Crichton Books, 2006; Drawn & Quarterly, 2016] was the first time I encountered such a feminine perspective [in comics]. I realize now it was the first graphic novel I owned written by a woman. I’ve reread it so many times, pages are falling out of my copy. She does not use speech bubbles, and she was truly doing it her own way. It was freeing to understand that graphic novels have no limitations, and here was a woman pushing away a boundary.

In addition to being a mural artist and illustrator, you are also known for your videography. Why does multi-disciplinary work interest you so much? Have you been able to translate work philosophies from one medium to the other, or do you believe that the inherent limitations of each form requires a kind of internal policing on your part?

I have dabbled in a lot, that is true. But I see all my practices as being linked, kind of like the MCU [Marvel Cinematic Universe] films. Each project I work on is part of my universe. There have been some stories I want to tell that only work in video form, and then some that I can only picture as a comic. I let the project guide me.

Cultivating what could be called, for lack of a better term, “an artistic temperament” is something creatives have to discover for themselves and learn how to hold on to. How have you navigated the relentless pressure to produce that every artist must inevitably push up against?

I was always going to be an artist. When I was a kid, I was always creating. Growing up, my mother was always good at fueling my artistic interests and making sure I found the joy in creating.

I don’t feel pressure to produce, because creating brings me joy and I love being productive. I have a pretty strict routine that keeps me going. However, I do spend one day a week sitting on the couch reading comics and watching TV to avoid burnout.

Sometimes artists are motivated entirely by creative decisions or in philosophies that will advance their work along aesthetic lines; publishers and booksellers can be cognizant of these incitements, but they are usually more preoccupied with the fastest path to market. Given your history as a bookseller, I am wondering if you reconcile these two elements in your work; if an understanding of what is selling at any given moment influences how you develop projects, whether by accepting or rejecting that data altogether?

Oh, I am always thinking about the market. I think when you’ve worked in sales as much as I have, you can’t turn that off. I think it’s invaluable knowledge to have, and I am very appreciative of my time as a bookseller. The sweet spot is finding something you find rewarding to create that will also sell. You need that balance. I don’t think there’s any problem with thinking about marketing while developing a piece.

You run the oneillreads Instagram account with your mother, the novelist Heather O’Neill. Where did your interest in book curation begin, and was there a reason why you chose that platform to promote contemporary literature you found exciting? Do you think that review culture, but review culture around books and comics specifically, is facing a crisis of relevance at this particular moment?

When we started the Instagram account in 2018, Bookstagram was just starting. I was really drawn to how positive of a platform it was. Mostly it was women posting beautiful photos of books they liked, and there were no negative reviews. Now, BookTok is on the rise and it is still incredibly positive. People never trash books on the platform. It’s all about recommending and promoting books you like.

So to answer your question, I think reviews are becoming more and more irrelevant with this new social media way of promoting literature. It seems like no one wants to read a negative review, or a long review anymore. They just want to be told what to read by people they have similar tastes to.

It’s unpredictable though, which publishers must find stressful. In the same way that random songs from history will go viral on TikTok, the same will happen to a book.

Through some corridors of publishing, there is an idea that the industry needs to undergo a period of calculated retrenchment in order to survive; that there are too many books on shelves and not enough marketing muscle to ensure visibility in a crowded ecosystem. Do you agree with this notion or do you believe that the advantages of maximizing things like bibliodiversity might outweigh the immediate drawbacks?

Readers are so diverse. There are so many different markets to tap into. If a book has a good plot and is well-written, it will find its people. Some books have short lives, and that’s okay. I don’t think there are enough graphic novels on the shelves, however. It is a genre that is still expanding.

Have you already begun the follow up to Est-ce qu’un artiste peut être heureux? Can you talk about what ground it will cover, and some of what its primary thematic concerns will be?

I am still doing graphic interviews for magazines, and I don’t think that will stop. I am working on a graphic novel right now in English. It is about my parents - my mother’s drifting, and my dad’s heroin addiction, and the way they were both these beautiful children who society threw away. I somehow came from that absurd pairing. It’s about the magic of survival, the opioid crisis, and the ways society profits off and exploits the bodies of the poor. It is very similar visually and thematically to Est-ce qu’un artiste peut être heureux? In it, I have a lot of conversations with my mom in the present day incorporated into the stories, and I am always breaking the fourth wall. I play a lot with humor and sweetness despite the heavy subject matter. It is definitely in the same universe.

You have edited two anthologies to date - a book of cat illustrations, and one on Victorian dating manuals. Are you planning on creating more projects in this vein? What is it about the anthology format specifically that engages you?

I like projects that include many artists because it widens the market. I started off with editing anthologies to help find a place within an existing community of artists. It was a way of getting to know people whose work I admired.

What are the largest obstacles that the publishing and comics industry are currently facing? Are there solutions available, but a lack of collective will is hindering its implementation? Or do you think that the problems are so multifaceted that progress can only be experienced generationally?

I think the role that social media is playing in promoting books is putting a lot of the marketing of a book on the author’s shoulders. We are living in a post-Rupi Kaur era where we understand that an online presence can really affect your publications. You are no longer selling just the piece of literature; you are also selling the author.

I think the literary landscape is always evolving and changing. It is not a bad thing.

How important is it to maintain the independent spirit of alternative comics, or of countercultural positions in the arts? Do you think that the transition of non-dominant forms into the mainstream is an inevitable trajectory, or something that must be avoided at all costs so that carefully curated alternative spaces can be preserved?

I think there will always be a market for weird and subversive comics. I worked at Drawn & Quarterly’s bookstore for five years, which carried the most amazing collection of independent graphic novels. That market will not go away, as long as we continue to support independent bookstores.

We are now seeing mainstream publishers putting out alternative twists to their classic characters. In 2016, Marvel had acclaimed author Ta-Nehisi Coates take on the Black Panther comics. Then DC had Mariko Tamaki write a fantastic Harley Quinn comic, and recently Jeff Lemire wrote a Joker story. I personally love this blend. There is no reason mainstream can’t be doing interesting and positive things.

I think independent and mainstream comics have been existing side by side for years, and I don’t see why they shouldn’t continue to live in harmony.