Liam Sharp has had a high profile few years after his acclaimed runs on Green Lantern with Grant Morrison, Wonder Woman with Greg Rucka, and Batman: Reptilian with Garth Ennis. Besides these big superhero projects, Sharp Kickstarted an art book and helped compile The Unseen Jack Katz, a collection of the legendary artist's previously uncollected work that Sharp and others worked on for free. These are just a few of the recent projects in a long career that began when a teenage Sharp turned down a spot at Oxford to work as an assistant to Don Lawrence. Since then Sharp has drawn hundreds of comics, including the acclaimed Vertigo series Testament, the bestselling Gears of War, and a Man-Thing series written by J.M. DeMatteis. He founded Mam Tor, a publisher that published two volumes of the Event Horizon anthology, wrote a couple novels, made a few films, and co-founded the publishing startup Madefire.

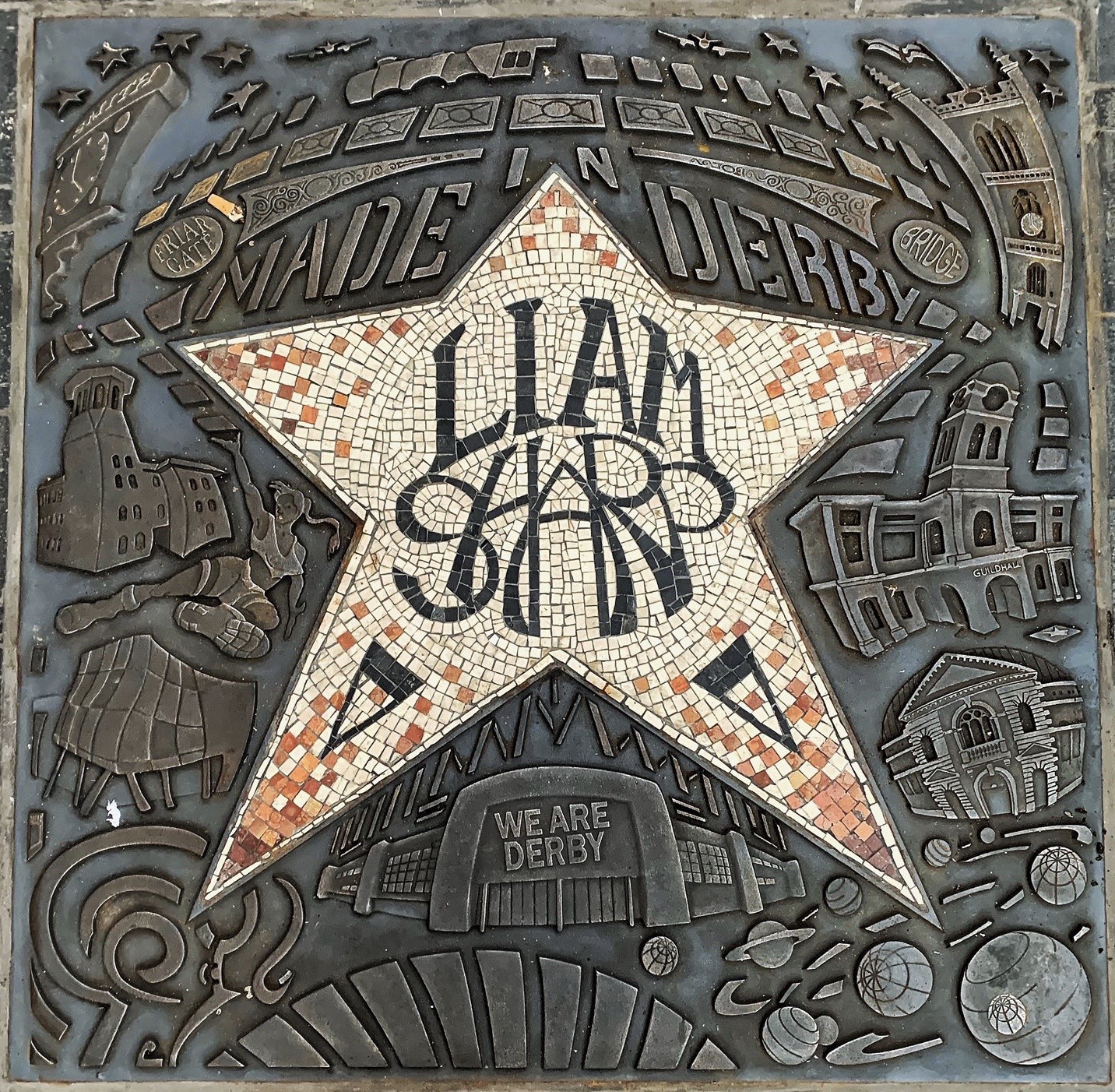

This summer Sharp is launching a new series, Starhenge, which he’s writing, drawing and painting. He’s also receiving an honorary doctorate from Derby University in his hometown. In recent months Sharp and I have had a lengthy series of conversations about his work and career. He worried how he came off, as he was honest about depression and setbacks, about luck and what it means to have a career. Not everyone wants to hear how hard a creative career can be, and Sharp is brutally honest about his own work, but I was struck by how passionate and excited he remains. He’s doing what he loves, and has never lost sight of that in a way that’s inspiring. - Alex Dueben

When you were young, what were the comics you read? I’m assuming you were an artistic kid who drew a lot, what made you interested in comics?

That is such a difficult question to answer in a linear way! In many ways my whole start in life was extremely unusual. I was born into a very working class family to parents who were themselves unusual. My mum grew up with little of anything. Her dad had been in the Navy in the Second World War and was quietly traumatized by it. Her mum had come from a more aspirational class and had wanted to be a window dresser or dancer, but ended up a mother in a two-up, two-down Victorian terrace. I still remember the rag and bone man with his horse pulling a flatbed cart up those narrow streets by the huge old mill. Somehow, though, in the ‘60s she had heard about a family in California looking for a nanny, and she applied. Whilst there she almost went to university in Washington State, but a phone call from her dad – really just the sound of his voice – brought her back home to Derby. That kind of thing was unheard of then.

My dad, on the other hand, pretty much left school at 12. He can turn his hand to anything – much like his dad – and could have been a great artist. His mum, my nan, had an incredibly vivid and lively imagination, and she took us round the world on her sofa. She had art all over the walls, cut from magazines. There were paintings of matadors and even a Pink Floyd poster in the kitchen. She dressed in wild colorful clothes and was quite the eccentric, but a fairly absent mother. My dad says it was his sister, my aunty Janet, that really raised him. In the end my dad became an apprentice mechanic, where he thrived, and eventually he also go a job that took him first to the US, then Nigeria. In the US he learnt all about these prefabricated flour mills, and in Nigeria he oversaw their erection and implementation. So my first three years were in Nigeria – which I have a few strong memories of.

We returned to the UK shortly before my 3rd birthday – a day I specifically remember. I woke up and proceeded to be sick everywhere. My mum cleaned me up and brought me down stairs. There had been a party and there were a lot of people in sleeping bags, and I remember on the hearth of the fireplace there was a row of matchbox cars and lorries – a present for me. And also a toy London cab, and LEGO – I loved my LEGO! My dad tells the story that I drew the taxi from every angle then never touched it again.

My uncle Ian – whose nickname was Chick, and who had a beard and long hair, listened to Hendrix and played the guitar – was my mum's younger brother. He was in the Merchant Navy and used to come and stay, bringing Mad Magazine with him. I'm pretty sure it was him that brought the first Marvel comic into the house that I can remember. It was a Daredevil comic featuring Gene Colon art and the Stiltman, along with Matt's supposed twin hipster brother, who was actually just Matt. It turns out to have been from 1967, a year before I was born. And again my dad says I drew, wrote and colored my first comic when I was six or seven. I recall it being about this lion-headed man and his eagle-headed winged friend.

But back then I remember loving many things – mostly fantastical. I love Harry Harryhausen movies, and sword and sandal epics. Friday night, when mum and dad went to the pub, I was allowed to stay up late and watch the horror double bill, which I also loved. The MGM monsters, and Hammer classics thrilled me. So it was never just comics informing my art, but it was always something in the realms of science-fiction, fantasy or horror. Mythic, magical, transporting material.

And of course there were the cartoons.

Somewhere along the way I really started to love comics though. I loved the UK reprints of Marvel material in black and white. And then Star Wars came along, and my grandma got me a subscription to Star Wars weekly, which had these fantastic back-up stories by amazing artists like Gray Morrow and Alex Nino. But also Starlin's Warlock and Byrne and Claremont's amazing Starlord. There was even a Starlord story by a young Bill Sienkiewicz featuring a Lion-headed character... These were all, it turned out, curated by Paul Neary, who would play a huge part in my early career later on. Also seminal at that time was The Trigan Empire by Don Lawrence, which I discovered in the small local library in Look and Learn Magazine. It was astonishing, beautiful stuff!

Me, my sister, and my cousin Dean formed what we called The Danger Club, and we all had to be superheroes. By the time I was around 8 or 9 I was drawing superheroes all the time.

Did you go to art school or study art?

By the time I was at primary school my art was really starting to be noticed. Two teachers in particular encouraged me and talked with my parents – Peter Rice and Eric Cohen. Both were very formative. Peter will forever be the voice of Gandalf, and he read us The Hobbit in year two of Lawn Junior School. Eric Cohen was only there for year three, but he made a huge impression on all of us in his class. He said to my parents, “you've really got to do something with this kid.” And they were very much “we know, but what?” My dad would have loved to have been an artist, so he was extremely supportive regarding that. My mum too. It was clear that was what I was going to be – that, or a writer – so there was never any question in their mind about that. Whatever it took, they would get behind it. I believe it was Eric Cohen that suggested the pretentiously named “Gifted Children's Society,” so off we went to visit that institution.

Once there they took me into another room and asked me to draw things – to make sure it was me doing it. And some time after that the chap who was running it had a suggestion. He had been the former headmaster of a private boarding school in Meads, Eastbourne, called St. Andrew's. They had had scholars of music, Latin, sport, you name it, but not art. So he thought it might be a good idea. My understanding was it was the first of its kind in the country, and it certainly opened the doors for many to follow. But yes, I ended up driving down to Eastbourne with my parents and being put through another set of drawing tests in a different room, and I won myself a 50% scholarship. The first in my family ever to go to such a school – which was a little frowned upon by some of my relatives, who were no doubt jealous. You didn't get above your station if you were in the working class, and that seemed to belong to another league of people altogether – which indeed it was! I was like Harry Potter at Hogwarts. This poor kid with a Northern accent, surrounded by princes and millionaires from all over the world.

From there I won a second scholarship to Eastbourne college aged 13, and at 17 I had the great fortune to meet the legendary Don Lawrence, who happened to live and work just outside of Eastbourne in Jevington! He had been looking for an assistant, and we met, and I was offered the job for the following year, after I left school at 18. Before that I had been offered at place at Ruskin College, Oxford, but here was the chance to do what I had always dreamed of doing, so I took it.

Tell me about Don Lawrence and being his assistant. What kind of work was he doing at this time and what were you doing?

Don Lawrence is one of the most legendary British comic artists of all time, though he was more famous, ultimately, in Holland, where he was eventually knighted – though sadly he died shortly before he could receive the honor. He was the first artist to draw Miracle Man (Marvel Man) and could have made a legitimate claim of ownership when it was all in dispute, but he just didn't want to be bothered with that. We did talk about it and I think it preyed on him a bit – mainly because nobody even thought to reach out to him about it! In that first issue Alan Moore wrote that was his art on the first few pages, reprinted. But it was his Trigan Empire work that most British creators remember him for, and his Storm work that made him a legend in Holland.

When I met him he was working on Storm: The Living Planet, and the next album Storm: The Twisted World. Both are extraordinary. He would spend up to two weeks painting a page. Just incredible. And he rarely used any reference. It was staggering to watch!

I spent weeks copying, pretty much brush-stroke for brush-stroke, his pages. The idea was that I would take over the title, and he would move on to something new. He had a dream of being a maritime painter. But over the year he just realized how much he loved Storm really. He wasn’t quite ready to pass the baton. I returned, many years later, to work with him on his last Storm album, The Von Neuman Machine. I co-painted the last ten pages with him. It was really tough for him knowing he was coming to the end of an epic run of seminal books. He had lost most of the sight in one eye to an infection after a cataract operation, and that was extremely tough to cope with – he was smoking a lot of weed then to help cope with it. I truly loved Don. He was my friend and mentor. I can still picture him perfectly and hear his voice and laugh. He was a tough taskmaster and likewise struggled with depressive periods, during which he could be quite tough company. But he was a giving, generous, brilliant man and I miss him enormously.

You said that your parents were always very supportive, but giving up a spot at Oxford to be an assistant to an artist, that must have been a heavy decision.

It was a very easy decision, and very much my own!

These were different times, and comics were terribly looked down upon by institutions. And my skill was an ability to either mimic styles or draw and paint very realistically. Our art department would annually be involved in a Barbican schools exhibit, which we would visit in London at the Barbican theatre. One one year I noticed this stunning art by a girl who was a year or two older than me. She painted like a Pre-Raphaelite – often self portraits at an easel. She had incredible long red hair, floral dresses, and would paint every detail of the William Morris wallpaper. It was captivating and brilliant, and impossibly accomplished. It turned out that she went to Ruskin ahead of me, so when I visited the college I sought out her work. What I saw was a room in which that natural skill and will towards realism was wrenched out of her. There were self-portraits round the room, one after another, becoming more and more devolved to the point that they just resembled the howling masks of the children in Pink Floyd's 'The Wall' movie.

Shortly after that one of the students from Ruskin visited our school, and I asked her what had happened to that girl whose art I so admired. And it turned out she had suffered a complete nervous breakdown. The school traumatized her, and stopped her following her own muse, her own vision, her own passion. And Ruskin was meant to be the college all about human figure work. Ruskin himself had championed the Pre-Raphaelites!

So I knew that if I went I would suffer the same indignity. My loves would be ridiculed. My passions would be looked down upon. What I wanted to do would be considered vulgar, and worthless. Frazetta and his ilk were to art schools in that era what Yes, Rush and Pink Floyd were to punks and music journalists – uncool, bloated, crap. Art schools hated everything I loved.

So no – the decision was very easy. One thing I knew with absolute certainty was – they were wrong. Any serious practitioner of comics knows this. And I was not going to let anybody tell me otherwise!

Was Tharg’s Future Shocks your first comics credit?

I can't recall if I was credited in Don's Storm: The Living Planet or not. I did a handful of panels in that. But yes, after a year Don decided he didn't want to pass on his character Storm yet, and I realized I didn't want to be a clone of Don, so he helped me get a portfolio together to show 2000 AD, and that led to a couple of pin-ups and that first Future Shocks story.

Was working at 2000 AD the goal or a goal when you were starting out?

Not really. I had gone through a bunch of different notions about what I wanted to do. I adore Roger Dean's Dragon's Dream and Paper Tiger books – showcases of fantasy and science fiction art and artists. For a long time I really thought I wanted to be an illustrator or book cover artist, like Boris Vallejo, Frank Frazetta, Jim Burns or Jeffrey Jones. I had also discovered Heavy Metal magazine, and the astonishing work of Richard Corben, Moebius, Liberatore, Bilal, and Druilet. Then meeting Don I felt like I had a straight line into European comics, which seemed more exotic and exploratory and adult. I was utterly captivated by that era, but by the time I was actually old enough that explosion of extraordinary work had largely come to an end, and it was the work being done in America that began to get really exciting. Miller and Sienkiewicz on Elektra: Assassin, and just Miller on Dark Knight. And of course there was Watchmen from Gibbons and Moore – both Brits, and Dave in particular being a stalwart of 2000 AD. It was an incredibly exciting time.

Were you a big Judge Dredd fan?

It was hard not to be a Dredd fan if you loved comics and worked in the UK. The world was a lot smaller then, and that was the primary venue to get seen in. I think as well that all of the influences of the seventies and early eighties were exploding in those pages. It wasn't just Dredd, it was Mills and Fabry – and later Bisley – on Slaine. It was the ABC Warriors, and Nemesis, and Bad Company, and Zenith. Amazing material! Back then 2000AD was selling 125,000 copies a week! And there was so much talent in there – John Higgins blowing our minds with his airbrush colors. Grant Morrison, Chris Weston, McCarthy, Hicklenton, Alan Davis, Steve Dillon, Phil Winslade, and on and on. Extraordinary times!

What was it like working with John Wagner and Alan Grant?

It was very hands-off back then! You were given the script by the editor and had no contact with the writer at all. But I got on with both of them, individually, at conventions later on. Alan in particular I became mates with – though sadly I've not seen him in way too long.

How did you start working at Marvel UK?

I had done bit and bobs for them when I first moved to London in '87. I had a studio in Islington with Andy Lanning and cartoonist Brian West. It was called The Cartoon Factory just off Upper Street. Andy was very good at selling himself. I wasn't. I was terribly shy back then and really struggled to find my voice, or the right words. Andy was hysterically funny and would have the staff in stitches. So he got The Sleeze Brothers off the ground there. I had inked a Count Duckula story that featured in an annual, and pencilled a Galaxy Rangers story, and an issue of the original Death's Head.

Around 1989 I moved to Derby, buying my grandparent's small cottage after my grandmother died, but it all went pretty badly wrong. I was only twenty-one and just had no idea how to run my finances or organize my work life. I craved attention as my school life had largely been very unhappy – lots of bullying, as happens a lot to those who largely stand on the outside of everything. So I would be in the pub every night enjoying my youth a little too heartily, and my work suffered. I got in a financial mess, lost the house, suffered a broken heart, and came very close to losing everything – so I moved back to London, and lodged with my great friend Brian West.

Brian really helped me get back on my feet. We would be up at 4.30 am in the morning to get a market stall at Campden Lock where we drew caricatures all day. I applied for a place at Bournemouth Film School – my comic experience was a shoe-in for storyboarding, but I fancied myself directing – and then I went to Dan Abnett's leaving party and everything changed.

Dan had been an editor – he did Strip Magazine, which I drew a story called Roark for, co-created and written by John Freeman. But he had decided to go freelance and concentrate on writing. He and Andy Lanning were starting to become quite a formidable team back then! And it was there I met Christina, who would eventually become my wife. I fell the second I laid eyes on her, and it turned out to be mutual – though I wouldn't see her again for months after that night.

Eventually I found myself having a meeting with Paul Neary – who had so profoundly instructed my early influences with his choices for Star Wars back-up stories – and he told me that he wanted to rethink and redesign Death's Head. He felt that there was an opportunity for Marvel UK to more closely emulate Marvel US and he had liked some art I had sent to John Freeman – for an unrealized Roark-Wolverine-Demon Hunter cross-over pitch. That night I faxed Paul a pencil sketch of a version of Death's Head, not really thinking anything of it. But that ended up the prototype for Death’s Head II.

Was Death’s Head the first longer extended run with a character you drew?

Absolutely. And it was insane how quickly that took off! Based on a black and white picture of that first four issue mini in Sales to Astonish the advance orders went from 30,000 copies – very respectable by today's standards – to a staggering 150,000. Paul quickly saw there was something there, so it was briefly delayed while they built more of a campaign around it. Dan Abnett writing. Top Marvel US characters guesting, and by the time we launched it got three reprints with silver and gold foil and sales of 350,000 copies. It was amazing, and changed my life as you'd imagine! By the time we launched the ongoing series featuring the X-Men, the comic had orders just shy of half a million – and it remains the biggest selling comic sold into the US market out of the UK of all time.

Was going from working at Marvel UK to Marvel US a big deal?

Everything seemed like a big deal at that time! Death's Head II was huge. We were on the Marvel stand in SDCC with an actor in a Death's Head II costume. Jim Lee invited me to join Image – which I declined because I thought Marvel UK would continue to be huge and Paul said Marvel would look after me. I was also now dating Christina (who as I mentioned earlier worked at Marvel UK, in the production department) and it was too soon to expect her to move to San Diego with me, and I really didn't want us to split up!

What was the first Marvel book you drew?

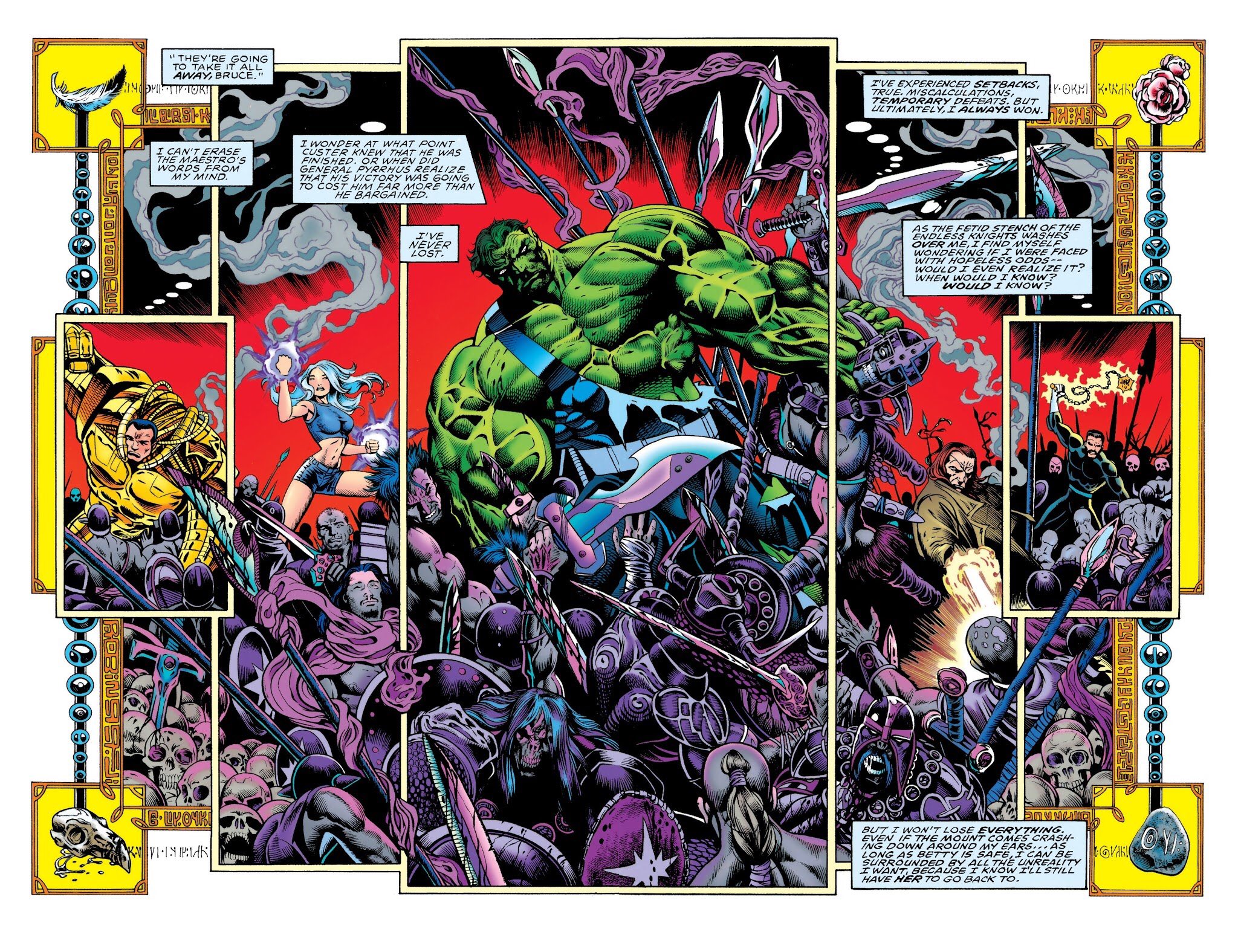

I think the first was a Venom gig, then a Spider-Man gig – thought it might have been the other way around! - and eventually The Incredible Hulk. It was all so much all at once, it seemed, and I was still so young really.

I wasn't, if I'm honest, quite ready for it all. I started to doubt myself quite a bit then, and lost faith in my work. It was incredibly overwhelming. I wasn't sure if I was doing the right thing, or if I was in fact any good, and I got really low at that time. It was the first tiny step towards understanding that I was actually clinically depressive – though it would be another five or six years before I realized I needed to actually do something about that! Back then people weren't really talking about depression, and there was still a lot of ignorance and stigma attached.

It was not a happy time working on that book, and sadly Peter didn't really like my work either, which cut the run short ultimately. I was casting about, desperately trying to find a style to define what I did. I was following this series of incredible runs by Todd McFarlane, Dale Keown, and Gary Frank, and I felt deeply inferior to them. I just didn't feel my work was anywhere near their caliber – which was frustrating, because I also thought it should be, and wasn’t sure why I couldn’t get it there - and I think Peter felt that too. We just didn't gel creatively – which was a great shame as I was a big fan of his writing back then. I desperately wanted to please him, but I couldn't, and I also had a sense I wasn't really drawing to my strengths. It was all a big muddle.

My inker at the time, Robin Riggs, used to try to help get me on the right track. He knew I was struggling and beating myself up. He even wrote to the editor suggesting that maybe they could steer the book towards something that suited me – something in a more sci-fi or fantasy vein – but nothing came of that. It all sort of fell apart and we eventually parted ways.

I wish I had understood what I was struggling with and been able to articulate it at the time – certainly now I would be much more communicative about my struggles and misgivings. I don’t think it would have taken much, really, to sort it out. But I needed to be able to voice that, and in those days I was – frankly – a bit intimidated by editors, and certainly by Peter! Throughout my life there have been periods when the shyness really kicked in, leaving me tongue-tied and feeling brow-beaten. And back then there was this sense that the right and only thing to do was to just knuckle-down and muscle through. That’s just what you did! It’s ironic that the art should be so vascular and imposing on that book – like the bottled-up frustrations and anger at myself were all exploding on the page!

The Hulk was one of my all-time favorite characters, so to get that book, and then to lose it was a tremendously heavy blow, and the start of a long spiral down towards a very tricky and bleak period for me.

Sometimes the lessons we learn are hard, and take a long time to land. I'm only now beginning to appreciate what happened then, and why. It's still sad because I don't think Peter or my editor had any real understanding at all of what I was going through, and I have no idea at all if it would have made a difference if they had.

You mentioned becoming friends with Alan Grant and you worked on some Batman stories together in this period.

The Batman stories were a blessing and a curse! They were offered under the condition that they be done in a preposterously short amount of time! I think I had two or three weeks maximum to pencil both issues, and I had to draft in help from Chris Weston and Edmund Bagwell for one of the two. The editor was in a bind, and, well, for me it was a case of do I not do it for fear of it turning out terribly, or do I take the chance for the opportunity of drawing the Batman? The artist, of course, wants to only leave great work behind, but the child wants to draw an actual Batman comic, and the pragmatist wants to keep a roof over his head and food on the table!

All in all it could have been worse, but they are certainly not masterpieces!

In that instance, too, Alan and I did not discuss it. It came directly from editorial in what now feels like another age.

You did some different projects with J.M. DeMatteis over the years starting with some Spider-Man and Strange Tales and a Man-Thing series.

Yes, Marc and I started on the Spidey story. There's a scene, actually, where the Peter clone is growing, and I had him emerge from that mechanical womb with long hair, and beard, and long fingernails – he had been grown in days, hours even! So that just seemed logical! But the editor was kind of horrified, and said no, you have to have him coming out looking like Peter! It's funny the things that people can get hung up on.

That aside, I really enjoyed working with Marc – whose Blood: A Tale and Moonshadow I deeply admired. We did Superman: Where is Thy Sting? too, which for me is not unlike the Magik story. There are bits I'm really proud of, but it's not terribly cohesive. Another of my frankenstein, cobbled-together monsters!

I look back at Man-Thing as one of the most creatively successful pairings I've had. That work stands up, and both me and Marc are very proud of it. Marc is a wonderful, poetic and intelligent writer with a big, compassionate soul. We had enormous fun on that series. And I was especially happy to have Christie Scheele coloring too. She had colored the peerless Bill Sienkiewicz on his Moon Knight run – which is and was a seminal, inspirational work for me, especially the single “Hit It” story, where Bill first became Bill. Just bloody amazing. You can see his influence in a lot of the Man-Thing work, along with Wrightson, and Jeffrey Catherine Jones. The “Atlantis” two-parter, from issues 7 and 8, remains some of my best work ever, I think. I would say that's the precursor to my Green Lantern run, even with a 20 year time gap between them.

Sadly Marvel was going through some upheavals at the time, and even though it launched better than expected – they predicted 20K orders but got 40K – when the sales halved they first folded the titles on that and Werewolf by Night into an anthology called Strange Tales, and then cancelled it after only two issues. Our editor Mark Bernardo, though, said at the time he thought our Man-Thing run was a future classic. There's still time for that to be born out!

How did you connect with Glenn Danzig and start working at Verotik?

He reached out to me. He was a fan of my Hulk work if I remember right.

I have not been able to find an issue so I have to ask, what was G.O.T.H.?

Government Operation Total Hate. The Hulk on steroids. It was a no-holds-barred brutal slugfest about supersoldiers gone wrong. I was trying to emulate Corben and Bisley and failing at both. It was drawn in a fog of self-doubt in a state of sadness – over losing the Hulk gig – and hope that it might somehow lead to something new, that was bolder and more mature. Something like the work I had loved in Heavy Metal magazine.

I remember going down to see Don Lawrence at that time, hoping he could help put me back on the right track. He was actually pretty kind about the G.O.T.H. work, but there wasn't really anything he could say about the inner demons I was fighting. It really felt like the world was falling apart at the seams. I didn't feel like I was in the right body, the right town, the right life. I didn't know what I wanted to do, where I wanted to go or how to get there.

I think that period was hugely damaging. I was making the very common mistake of judging myself against my peers. Trying to grow artistically through emulating others I perceived as better, greater and more successful than myself. It's the worst thing an artist can do, but it's an easy trap to fall into – especially if you have skills of emulation! You really have to put the success of others to the side and not worry about that. It's so important. But it's easier said than done, and there's no road map for this industry.

I was recently looking at Yesterday's Lily, the Jeff Jones art book published in 1980, and there's a bit from the introduction by Irma Kurtz that really struck a chord: “There is no requiem for artists presumed dead, it is one of the hazards of their vocation to be absolutely unknown as soon as they fail to be memorable.”

Death's Head II had been huge. The Hulk even moreso. Then there was G.O.T.H., and a slow slide away from the visible or memorable. I could feel my grasp slipping, and the clouds beginning to cover the sun again. And I was helpless to do anything about it.

You mentioned being a big fan of Frazetta, like so many, talk a little about working on Death Dealer.

It's difficult. As I’ve said, I was traumatized from my Hulk experience, and a little in awe of Simon [Bisley]. He burst onto the scene with such force and presence, and his work embodied everything I ever wanted to see in my own work – the power of Frazetta, the physicality and fearlessness of Corben, and the dramatic, inventive approaches to painting of Bill Sienkiewicz. In a strange way it felt like he had swept in and stolen a space in comics I was hoping to one day occupy! And he was so bloody good at it!

The net effect was to almost deprive me of a direction to head because anything I did was going to look like imitation. He got there first. I was not bold enough, fast enough, or fearless enough to do it before he did. Of course, being offered Death Dealer after Simon was something I couldn't turn down, and I really tried to capture something of Frazetta's work in my pages – at least for the first volume. I look back on those times with a very little fondness. The stories were mostly violence, gore and gratuitous nudity. There felt like very little nuance or subtlety or reason for being – beyond that gratuity! I know some people love those books precisely because of that, but I do like my work to have a little soul and a little heart! Simon was much better suited to that kind of mayhem!

I was in a complete state mentally, and sinking increasingly lower after my Hulk experience. And I was briefly enamored of the allure of false idols – of a rock and roll dream that truly never was. The shy, sullen kid with no friends was now a beefy 6’2” long-haired wannabe rocker hanging out with the real thing – but inside I was still the same timid kid that hated himself. No matter how much I pretended to embrace that material, and told myself that by daring to be so brash – to fearlessly draw work that might shock and awe the reader – it was not at all representative of who I ever was, or am, or will be. It was a sham. It was all bullshit. And it wasn’t – to my mind at least – true to Frazetta's vision either. Frazetta was much more sensitive in his work, for all the blood and thunder. It had romance, which in my work was completely lacking.

Later Frazetta was quite disparaging about my art in his book Icon, which was another moment that really broke my heart. I have never felt a more painful body-blow from an artistic hero. To my mind I had done precisely as I was asked. I drew the script (such that it was) I had been given, and as well as I could. I believed and had been told that Frazetta approved every page personally, and that he liked it. So reading his less than generous thoughts regarding my work was utterly, shatteringly disheartening. It took me a very long time to get over that. My dear friend, Joe Jusko, much later on told me Frazetta had really liked my work, so why the opposite was stated in his book I'll never know. I sadly never got to meet or talk to him. It can be rough working with your heroes!

You also drew a Magik miniseries at Marvel that Dan Abnett and Andy Lanning wrote.

That was an interesting one that doesn't quite hold together. I saw it recently and it's better than I thought, but it was very experimental in an uneven way. I like the energy there, and the covers hold up quite well, but it's not a patch on my Man-Thing work!

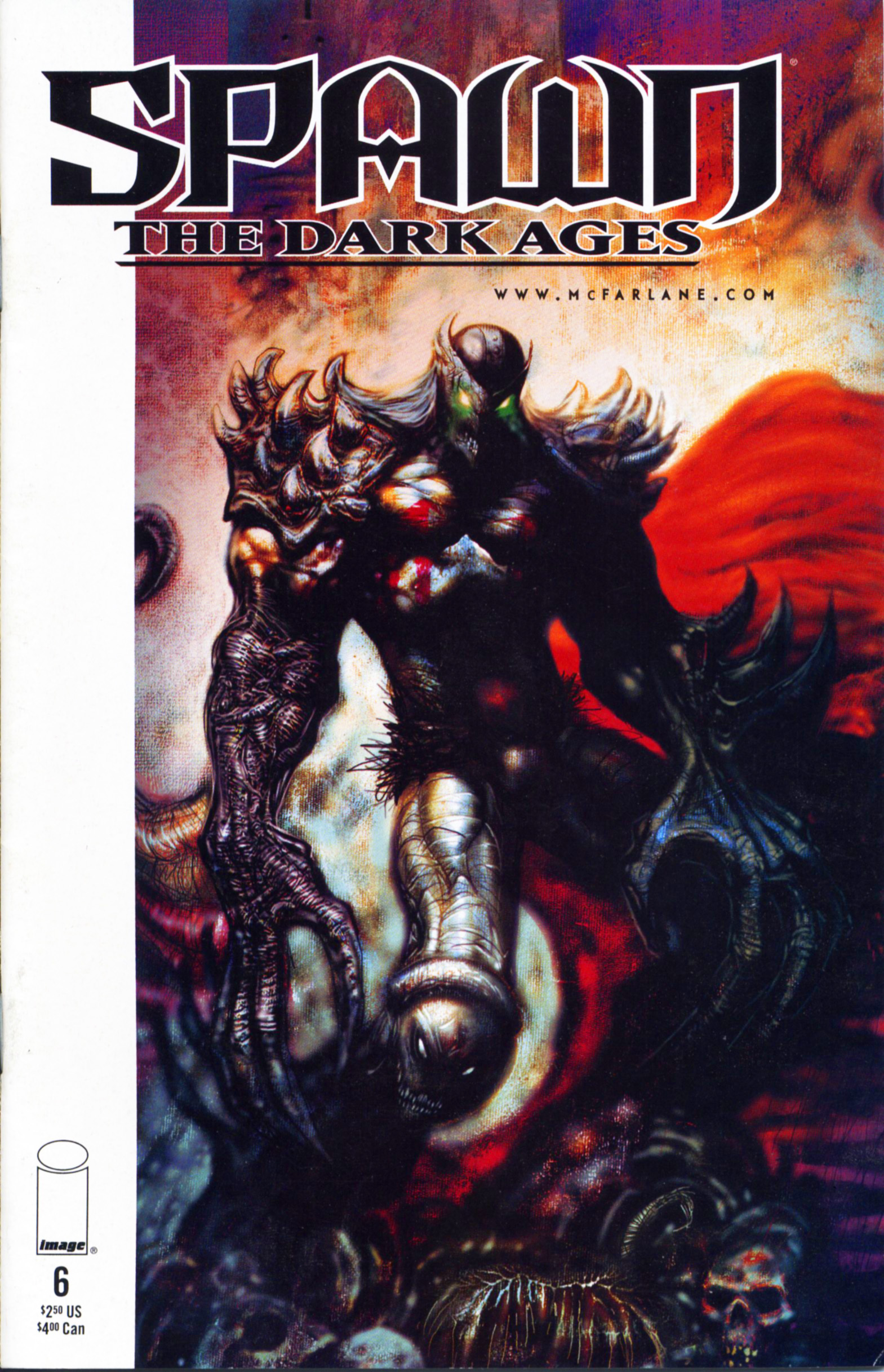

How did you end up drawing Spawn: The Dark Ages?

I'm pretty sure McFarlane saw my Man-Thing work and loved it, and they came to me.

That was yet another time I look back on with some mixed feelings. It started really well, and I hoped it would be a bit of a comeback. It was Spawn after all! And off the back of Man-Thing I was feeling that there was something coming together in my work, and the first issue has some strong drawing and nice set-ups. I was pencilling, inking and co-painting the covers with my friend, the astonishing Glenn Fabry – who lived not far from us at the time. I put so much effort into it, but there was very little guidance editorially, and a lot of mixed messaging.

Myself and Brian Holguin, the writer, conceived it as medieval tales, for which each story would have a slightly different vibe, as history and time changed the details. The idea being that creatively we could try different approaches – which was something I had really loved about working with Marc DeMatteis on Man-Thing. But in reality the monthly deadline meant I was always running to keep up, and I was having to let some of the work go that I wasn't satisfied with because I didn't really have enough time to rework things if and when they went wrong. Because of that the resultant series is very uneven – though there's still a lot I'm relatively pleased with, or certainly was at the time!

McFarlane, though, wanted a book without magic – he was obsessing over Braveheart – and that's hard for a book about a zombie from hell! The change didn't come quick enough for him, and I read they had replaced the writer online. When I inquired if that meant I was also replaced, I eventually got a call confirming it. It was just before Christmas, 2000, and my wife was about to have a baby, and all of that led into some of our most difficult times as a family ever. I thought I was finally coming out of that slide at the time – lots of Man-Thing had been great, and Spawn had started really well – and it turned out to just be a brief respite.

But you know what? Out of adversity, as they say! It's how you address these things, and where you go next, I think, that really tests who you are. Ultimately we sold up our house in Brighton, moved back to my old hometown, Derby – which was much cheaper – and we started anew.

Another book that I read when it was released was The Possessed. I was not impressed by the story but I did like the art.

I'm sorry the story didn't land with you. I actually really liked the characters – it was like a dark Ghostbusters premise, and full of homages to other stories. We had high hopes it might end up a film, and I believe there were significant bites, but unfortunately nothing was to become of it. Though Geoff Johns went on to bigger and greater things, I hear. [laughs]

You also drew an ABC Warriors story that Pat Mills wrote for 2000 AD around this time.

I adored those characters, and put a lot of work into the pages, and yet it looks like a terrible mess to my eyes now. I think you have to be disciplined in the layouts and storytelling to pull off that kind of explosive art. My early career is littered with great bold leaps of creative faith in the artwork that is unfortunately not backed up by good enough storytelling. To me the storytelling is – it took me a long time to realize – more important than the art. Great storytelling trumps great art every time. A book can be beautiful to look at, but if you can't read it then it fails as a comic, no matter how heroic the intent.

That ABC Warriors story falls into the category of “heroic failure” for me, I'm sad to say. Some of the original pages look really impressive – I genuinely was trying hard to make it great! – but on the printed page it just didn't come over well. It’s kind of a mess.

You also wrote and drew a Vampirella story and drew a Vampirella/Witchblade comic.

I did! It was post-Spawn, and I was clawing my way back into the industry. I met the editor in San Diego – my friend, the inker Michael Bair, was taking me around the con, introducing me to everybody. It was the first time I had hustled for a while. When you're on big books the work comes to you – more than you can generally handle actually, because you are visible! By then I was a long way under the radar, so I was having to pimp myself again, which frankly I'm not at all good at! But yes, I was invited to do that eight pager for the magazine, and I still think it stands up well!

I did absolutely everything on that one – wrote, drew and lettered it. I hoped it might lead to more work on the character, and I had a big pitch for a story on her planet, where pirates sailed on seas of blood in galleons made of bone with sails of flesh, but sadly the publisher, Harris, was somewhat embattled and soon after the Vampirella IP was sold on. So that was the end of that!

In this period you also inked Glenn Fabry in an issue of Global Frequency. Which is something you don’t often do.

Again, it was post-Spawn, and I hadn't been able to get any work. A trip to New York and the DC and Marvel offices had proven unfruitful. A big Conan pitch fell through. A Death's Head II reboot with Bryan Hitch co-writing had been nixed. A Wolverine story, in which his adamantium rib cage had been a prison for a demon – kind of an unofficial spin-off from Man-Thing using characters Marc and I created – also never happened. An illustrated book for ComX came to nothing after four months of working on it. A series for Wildstom called J.U.N:X, that Jim Lee loved, also got dropped. And I spent months talking to Don Lawrence and Dave Gibbons too, about taking over Storm, with Dave writing, but we couldn't make that work either. It would have been amazing based on the work we did for the pitch, and hugely ambitious.

I once worked out that the sum total of pitches I made in the year following the end of my Spawn: The Dark Ages run, in terms of the number of issues and time it would have taken me, was something like 135 years of consistent work that fell through my fingers! I made six thousand pounds in total that year, with a family of five to support. You don't get paid to pitch!

We had to sell our home, move to Derby – as I mentioned. It was the bleakest time of my life I think. Nothing landed. Everything failed. So I took anything I could get, and that ink job was one of them – offered by Glenn out of kindness, because he knew what we were going through. All of it off the back of things going wrong on The Hulk. So it was then that I finally went and got some actual help, and started working on getting myself well again. My friends from that time will tell you how down on myself and my work I was. I still fight a tendency to do that, but it’s less all-consuming now. I tended to put all of my failures on myself, and there were long stretches of time I never wanted to draw again. I even went as far as to say I hated it! The pencil felt like a dead weight in my hand.

And yet I knew I had a family to support, and after all – what else was I going to do? In the face of adversity you either give up and go under, or you put others first and you find a way to rally. Of course, when you suffer with a deep depression you’re not seeing anything clearly, and the gap between what you feel in your heart and what you know to be fact is huge. You can be presented evidence of your worth and still not believe it. But I loved my family, and that was the galvanizing factor. I had to go on because I had to go on. They were more important than me. And in many ways that knowledge saved me.

There are a fair number of comics people who have played in bands, but tell me about this band with Charlie Adlard and Phil Winslade. Was it an all comics band?

It's true! I've been in a few!

Dutch Sugar was our late ‘90s crossover-neo-prog pop-rock group featuring an amazing didgeridoo player. In that band I wrote half the songs for and played acoustic 12 string, as well as being the singer.

Then I spent a year as the singer for Made in Japan, which was mostly Deep Purple covers, with some Floyd, Queen and Led Zep thrown in. That band was truly epic!

The one with Charlie, Phil and Paul Birch was created in haste to play at the opening night of a Birmingham comic convention drink-up. It was called Giant-Sized Band-Thing. We had about two rehearsals in less-than-ideal venues, so it was very seat of the pants! But after the con we started convening in Birmingham where Phil lives, and working on more material – some of it our own. We only did two more gigs – one at Charlie's local comic shop, and one in Derby, which was a sort of send-off for me as I was moving to the US. The last one was great. We had a huge turnout and a support act, and the sound was the best we'd had.

That's ten years ago now! Madness. I miss gigging, but it's hard work when you're dragging your kit around and setting up yourselves! I still have a dream to record an album one day. I miss song-writing a lot. It's the main thing I had to give up when we moved because I just no longer had the time it requires. I'm working on changing that.

You spent some time working in Hollywood. What kind of work were you doing?

Concept design mostly. I had some fun on the Lost in Space movie painting cityscapes and early production designs for the robot. For Small Soldiers I designed the main hero toy, Archer, and his assorted band of Gorgonites. (I'm frustratingly credited as “Laim Sharp” on that, which reads as "Lame Sharp”! You have to laugh!) I also designed a bunch of alien-style costumes for Tim Burton's unmade Superman Lives that would replicate Clark Kent's super powers after he lost them. I featured briefly in the documentary about it by my late great friend Jon Schepp, The Death of "Superman Lives": What Happened?

It's fun work at the early stages, when there's a blank canvas and you can basically do whatever you like until it strikes a chord with the director! That happened on Batman Beyond. My first sketch of a Batman with a full-face mask and bat wings was pretty much what ended up on the screen. It can be a lot of fun, but you have to be prepared to let your work vanish into film lore, the wider collective of creators, and sometimes never be seen. I have no idea what happened to any of my Lost in Space paintings to this day.

You’ve also made some short films and wrote a few scripts. And I have to ask about adapting A Fistful of Blood and the animated series Ring of Fire.

My friend Digger Mesch had purchased the rights for A Fistful of Blood and wanted to shoot in China – which presented a bunch of problems as you can imagine! Fistful is very graphic, with a lot of nudity, and there's no way that was going to fly with Chinese funding. So it was constantly under development. I pulled a great team of creators together to contribute to the mood book, and there was a screenplay by Kevin Eastman that was a huge 200 pages long – really wild, midnight movie stuff in the vein of Jodorowsky's El Topo – but Digger knew he couldn’t shoot that one; it was way too long. The new screenwriter Digger had lined up had delivered nothing and went AWOL about a week before a big finance meeting, leaving Digger – who was going to direct it – with nothing to show beside the mood book. So, being a writer, and having had endless conversations with Digger about the look, feel and characters, I said I would write one for him – in a week! Which was nuts.

And it was not easy, because of the stipulations imposed. They needed a Chinese male hero – which was nowhere in Kevin and Simon Bisley's story – and Digger had this great idea for a circus troupe of freaks and performers that has become a renegade band of hired killers. This was 15 years ago now, so it's been interesting seeing some of these things kind of manifest in various different ways. We kept the lead female, but made her much more of a Clint Eastwood woman-with-no-name character. Very much NOT a victim. There was a role for a gun-fighting preacher written for Kevin Grevioux, and there was still a big alien element. Given the time I had, I still think it worked and would have been an entertaining action horror comedy.

The whole thing fell apart though, sadly. I know Kevin Eastman did not like my script at all – though I’m not sure he got past the first ten pages, and that bit hadn’t been written by me! Simon Bisley said Kevin thought it was “shit.” I was pretty pissed off, because I put about two to three months work into the art, the book, the script, all for free – mostly because they were my friends! I remember saying to Simon – well thanks for that, mate, because I know you would work for two months free for me, right? Because you admire me the same way I admire you? Which, of course, he never would have!

So it was a bit of a lesson learned. I used to do a LOT of work for nothing for friends – a lot of artists do! – but you can't sustain it, and you get seriously taken for granted after a while. I won't do that any more.

Ring of Fire was pitched to channel 4, if I remember right, with my great friend Brian West producing. He had a TV series called Pets running, which was an adult puppet show. Ring of Fire was Lord of the Rings via South Park. I had learned to animate on my computer, and figured out how to do very simple cut-out style animations, but with epic rendered backgrounds. It was all going very well, but the TV company suddenly replaced their head of comedy, and it was all change. Ring of Fire was one of the casualties.

If any of these things had taken off it's hard to imagine what I'd be doing now! I think my biggest regret was Planers not taking off. That was an original screenplay I co-created with my wife Christina, and Phylis Carlyle – who produced Se7en and Accidental Tourist – really loved it. She encouraged me to write about 14 drafts over the period of a year. It was really Ready Player One with a psychedelic aspect – to do with a game that actually pulled you into the astral plane, not an online world. We were way ahead of the curve on that. Huge shame. We got so close!

There is this decade, between the Hulk into the mid-‘00s where you were working – though I know freelancing “steadily” is a complicated thing – and you were doing different things and adjusting your style, but I feel like it wasn’t until the 2000s that I started to see “your” style. I don’t know if you agree, but I’m curious what that period felt like for you.

No, you're bang on! Because of everything I just mentioned we were broke and desperate – and there is literally nothing that will send people running faster than a faint whiff of despair! You end up in this horrible catch-22, where – due to circumstances – you are literally desperate, and literally depressed to your core and worried sick. I couldn't even get an art agency to take me on because I was too “comics-y.”

The industry starts to think there must be something wrong with you because nobody is hiring, so it spirals very quickly, and yet you have to put yourself out there as though everything is fine - stand tall, appear to believe in yourself. It is very, VERY hard! And I'm hugely thankful to my friends that genuinely helped, because there's also a tendency for people to close ranks. Previously successful people not getting work is not easy to witness, so people start to look for reasons where often there are none. It can be purely circumstantial.

So what we did – myself and my wife – we thought "sod it. If nobody will hire me, then maybe we should become publishers ourselves!” That led to Mam Tor, and the two Event Horizon anthologies. A wonderful, terrifying illustrated book by Matt Coyle called Worry Doll, which is truly incredible. And also three novels, including my first well-received novel, God Killers: Machivarious Point and Other Tales – which is getting published again, along with a sequel and collected short stories of related material, in three separate volumes next year by Reuts Publishing here in the US.

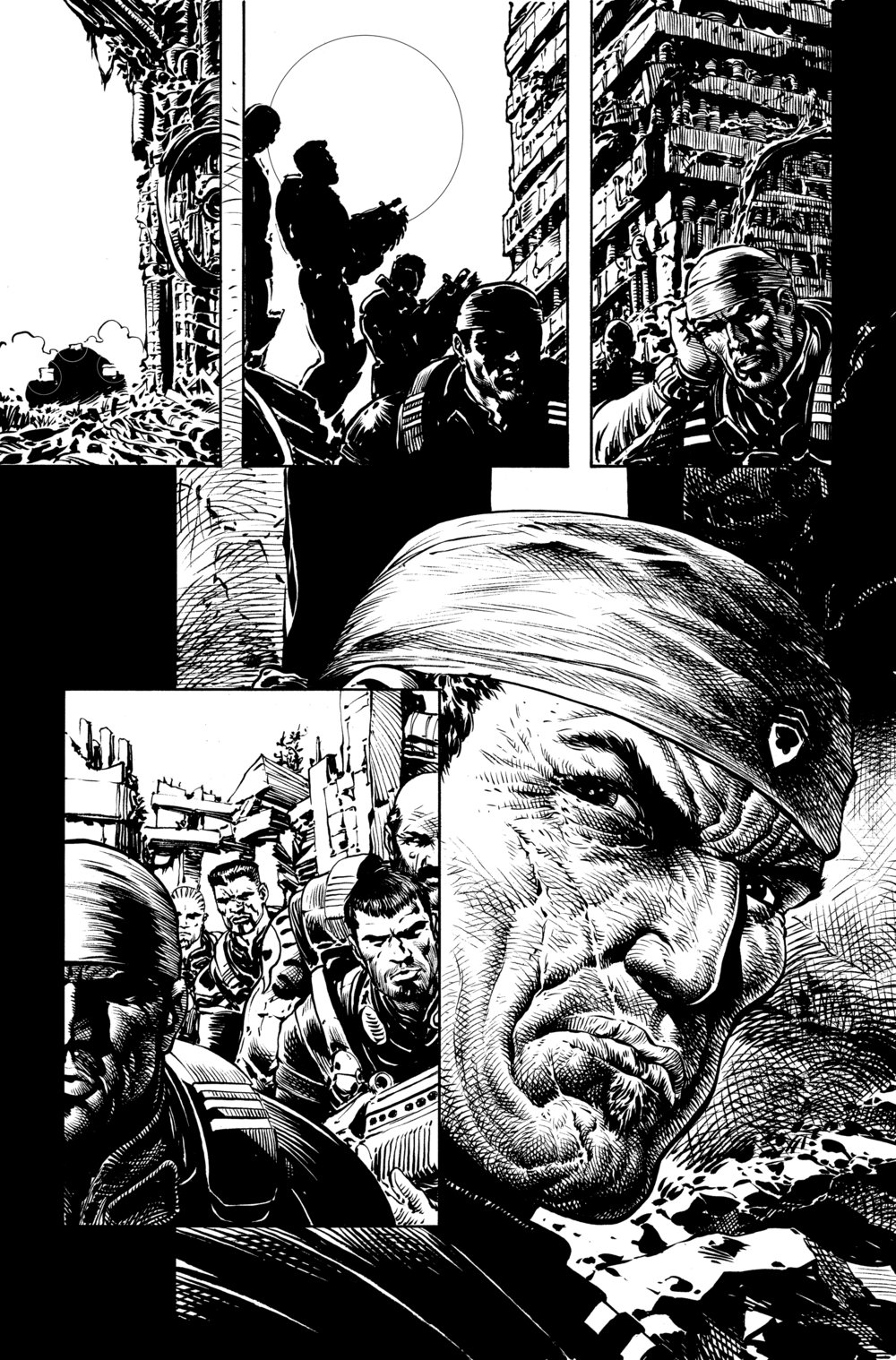

The long and short is that Mam Tor led to some huge advertising campaigns – for Coke, and Time Out and working in conjunction with the Mother London agency. It put to bed any notions there might have been around why I had not been getting work. And it recast me as somebody of significance – certainly within the UK comic scene. That led to Testament, and eventually to Gears of War, which was the biggest selling comic of 2008, and I think it is the most solid piece of work I had ever done up until that point in terms of clarity of storytelling and a very disciplined approach to the material. To my eyes that's the work that set the template for how I would handle Wonder Woman a few years later.

I know how hard it can be to get work and how desperation seems to make people want to hire you less. But as far as coming into your own, was some of it finding the right project, was some of it coming to an understanding about how to balance storytelling and art and how you thought and worked? Was it just finding the projects that clicked in a certain way?

I think it's a combination. I'm aware it all sounds like a bit of a hard-knock story, but I sincerely hope I'm not coming across as either somebody inclined to blame others for their perceived failures, or somebody perpetually unhappy in their work! It is a beautiful medium, but I'm keen I don't sugarcoat it or present something that isn't true – either from a personal or industry perspective.

As to when I came into my own – that's quite a hard thing to pin-point as there were times in other decades that my work tapped the zeitgeist a little, and when I felt that I already had. Death's Head II was huge, so in that moment I felt very much that I had come into my own, only to lose that sense later on. Again, on Man-Thing, I truly believed I had found my voice, and tried to carry that through to Spawn: The Dark Ages – but somehow lost that impetus and certainty. Then again on Gears of War, which was a stylistic precursor to Wonder Woman, and from Wonder Woman onwards I've felt more comfortably me being me.

I'm perpetually fascinated by the possibilities inherent in the medium though, so I can't imagine ever completely settling into one technique, but people tell me they can see what they regard as my style now – be it in a traditional brush or pen and ink approach, or the more fully painted material. That's good to know. And certainly, working on projects that excite you is a big part of what makes any work land.

Looking back on all those failed pitches from that period, are there any you really wish you’d gotten to do? Or has time just moved on?

Some come back around. The illustrated book for ComX became my first novel, God Killers. J.U.N:X was state of the art for the time, but would feel behind the times now as so much has been subsequently done with the concept of nanotech. The Wolverine story was too weird – very much inspired by the new weird movement in literature in the ‘90s. I don't know how that would be regarded these days! I’m working on something related to it with another artist though, for possible release in 2023.

One story did eventually became my The Brave and The Bold series. Things are always getting recycled!

So what made you want to write a novel?

I have always written. It's something I truly love. As much as making art. I used to write short plays, poetry, tons of songs, and stories. God Killers started as a comic when I was 12, inspired by a James Cawthorne adaptation of a Michael Morcock book, The Jewel in the Skull. Later on, when I was around 19, I started an epic fantasy prose version, but only got about four chapters in. Then I pitched it as a comic, to no avail. Then an illustrated epic poem. Then finally I came back around to the idea of just writing a novel again.

I've had two novels published – God Killers, which Mam Tor published, and Andrew Wilmingot's Paradise Rex, Inc. from PS Publishing – which is a very different, extremely personal book, and more or less a meta self-portrait – very experimental and postmodern. I've also written a sequel, of sorts, to God Killers called Caged Aurora, and a volume of related short stories. These will be coming out as three new volumes from Reuts Publishing in the near future, which I'm delighted about.

For the two Event Horizon anthologies, the first especially, was a lot of it reaching out to people you knew and saying, let’s do something for ourselves and go crazy?

There had been a lot of chatter at conventions about the way the industry was going – less work, less opportunities. I was meeting some wonderful creatives at shows and on my old message board, Sharpenings, and it just felt like we had some real impetus. Established creators longed for a venue to cut loose and have fun doing something short form that they owned. Unknown talents needed a platform to show their wares. The concept of a combination of both seemed to make sense. It was really exciting at the time, and the kind of concentrated distraction I needed to lift me out of what had been a very dark, desperate place. The whole Mam Tor experience was very joyful and brought a ton of people together from all sorts of spheres. We made a music CD, two films of Zombie Elvis – our mascot – and became a bit of a creative family for a few years. I made friends for life during that time – Dave Kendall, Emily Hare, Emma Tooth, Ali Powers, Kevin Crossley, Lee Carter – all brilliant people who have gone on to have wonderful careers. Very special times, and they opened all sorts of doors.

Right now I have volumes of Event Horizon and Testament on my desk and I think of these projects as when you hit that next level as an artist. Both because they came out in a similar period and because one is more painted art and one pencils-inks.

Very kind of you to say! It was the first time that I can remember that I got to publish something where the chains were off and I could try anything.

How did you end up drawing Testament?

I actually can't fully remember! I suspect I was pitching myself to the editors at DC and Vertigo and finally got a bite!

In a lot of ways the book required you to do many things as an artist, which I’m sure was the appeal. I mean broadly speaking you drew the Biblical stories in one style and the main story set in the near future in another style. Very detailed backgrounds with lots of gutters and design work.

There was lots of appeal there. I'm a bit of an armchair anthropologist. I went through a a Christian phase at school, before I became a de facto atheist after drifting through Buddhism and new age hippy stuff, but I always loved the stories, and the speculation of what lay behind them – the mix of archeology, history and anthropology which is constantly being rewritten. So I was delighted to get to work on a book that wore it's intellectual credentials on its sleeve, and wasn't just blood and thunder – though of course it was a bit of that too! I wish I had been a bit bolder and utilized more of what I had learned on Man-Thing. To my eyes the art is a little timid, and leaning into the mainstream – which was entirely a conscious decision as I was thinking about my future beyond the title, and what might come next. I was terribly afraid that if I didn't do that I would draw myself back out of the industry again, and I have to confess that I had a strong desire to at least try and get on a book that actually enjoyed a substantial readership!

Douglas Rushkoff is this fascinating character. How did the two of you work together? Because Testament is a book that is very high concept, very much writer and plot driven, but it’s also a showcase for an artist, in a way that a lot of comics are not.

Yeah, he's great. I have read a few of his books, and I still follow his posts on Medium. There wasn't a huge amount of interaction, and we have so far failed to meet in person – though we tried a few times. I adored his thinking and outlook. It was a book of futurist punk anthropology drawing on history and mythology to imagine a mythic utopia. What's not to love?

So after Testament was canceled, how did you end up drawing Gears of War? I think a lot of people ignored the book, as tie-in books are generally ignored, but it was also huge among gamers. You took it very seriously and before you described it as the precursor to Wonder Woman. What does that mean?

Well I think it was the first time I truly stopped worrying about style, and put the storytelling first. I tried to draw it as well as I could, in a realistic, illustrative way – as much as giant, muscular guys with vast chain-saw guns in suits no real human could ever move in can be considered realistic! I was actually quite resistant to doing the book as I felt like I really wanted to do a classic superhero title again, but it was on the table, they really wanted me for it, and while I'm not a gamer my wife said “look, you could have easily done all these designs yourself!" So I reframed it in my head as a sort of Conan, barbarians-with-guns, comic. I treated it with respect – not as a licensed title, but original IP – and put everything I had into making it as good as I could. And that's similar to the approach I had on Wonder Woman – story and storytelling first, which I just tried to draw it as well as I possibly could, and not just go for stylistic flourishes.

You're right though. While it was the biggest seller of the year with 450,000 sales, that was mostly the gamers. The comic press and fandom barely registered it, sadly. I had secret hopes it would cross over.

Around this time you also wrote and drew Aliens: Fast Track to Heaven. Admittedly I'm much more of a fan of Alien than Aliens, so I enjoyed it.

I'd been on and off talking to Dark Horse for a while, since I'd pitched a Conan story that sadly I never got to do – one more of those many pitches that never saw the light. As I remember it, Chris Warner and I talked at San Diego Comic Con, and he mentioned the idea he had for a line of “graphic novellas”, starting with Alien as the test bed. I immediately said how much I loved that franchise, particularly the first movie and the wonderful Walt Simonson adaptation it spawned, and I pitched a few ideas. One was a barbarian planet, the other was what became Fast Track. It kind of went under the radar, but I think it's a solid little short story very much in the universe of the first movie, and I still think it holds up as a good concept.

Tell me about Madefire. Where did this endeavor start?

That's a big, difficult one!

After the third volume of Event Horizon failed to get enough orders to be viable – way before Gears of War happened – I kind of accepted that the troubles the print world was enduring were getting very real, and it became a question of how you address that - particularly as comic writers and artists. It was clear that the internet was showing signs of being the obvious next place to publish, but there was a question of how you avoid the work being copied and pirated. The upside, though, was that there could be a massive reduction in costs for up-and-coming talent to produce work, but that it also presented some interesting opportunities in terms of how a medium might evolve.

I started talking to my fellow pros at shows, and that revealed who was prepared to try these things, who was on the fence, and who was completely against the idea. For many it seemed like a threat, but I saw it as potentially a new gateway for young readers who no longer saw comics on spin racks in every major store or news vendor. And I also guessed that it was going to happen regardless of whether or not we – as an industry – got involved or not. It was very contentious back then, in the same way NFTs are currently, so it was a little daunting taking that fight out into the world, but as a creator I felt I didn't have much choice if I wanted to get my own creator-owned work seen. I didn't have the cache, or a big enough loyal audience at that point, to sustain a printed creator-owned series, so going digital, at least conceptually, made sense. I also thought there might be a way to really grow a big, new audience online. And the more I thought about it the more it seemed viable.

Around this time I reconnected with Ben Wolstenholme, who I had given drawing tips to when he was a kid. He'd become the next art scholar at St. Andrew's and had gone on to form a successful branding agency. I pitched the concept to him and he loved it, so the two of us then developed and pitched the idea around London. At that time I wanted it to remain Mam Tor, but Ben wanted it to be Madefire, which was a company he'd created and kept in stasis. We got a lot of interest, but ultimately nobody took the plunge. Ben then moved out to the US to set up a branch of his agency in San Francisco, and about a year after that he unexpectedly got some interest in Madefire from True Ventures, a venture capitalist outfit in the area. They wanted us to bring a tech founder in, which is how Eugene Walden became involved via their recommendations, but basically said they would lead the first funding round. It was incredibly exciting at the time!

So that was why we moved out to the US from the UK. I had suggested to Ben that he and I should both be CEOs, but that was shot down quickly, and rather painfully for me it has to be said. We both started with equal shares, but he brought money to the table from friends and family, whereas I brought all the IP and talent – sweat equity, which does not equal share value – and that meant he could award himself an extra 20% of the shares. After some heated wrangling I became the CCO. Ben the CEO. And Eugene joined us as the CTO.

I had thought I was the de facto leader up until then, but from that point on I wasn't really leading the company any more – not even co-leading as an equal partner – though I did lead the content and the development of the platform. I was the first to use the proprietary tool Eugene developed, making the first so-called “Motion Book.” (I wanted to keep the term “comics" personally, but was over-ruled.) We really were the first to widely develop and establish the grammar and timing around the kind of moving comics you see all the time now, promoting new titles, or in TV show opening credit sequences and so on. We were the gold standard for quite a while.

We had recruited Ben Abernathy – my former editor on Gears of War and The Possessed, and now the Batman group editor. A lovely bloke, and a great friend. Joe Elardy was my right-hand man running the teams that built the motion books, with Kevin Buckley doing assistant edits and in-house writing, before eventually running content after I left. There were some amazing, talented people working there. Friends for life. We could animate faster, cheaper and better than anybody else in the world – no matter who we outsourced to in moments of need – and the ability to respond to the multiple challenges we were consistently posed was legendary. The production team was the unsung heart and brilliance behind the endeavor and I have nothing but respect for them. I'm very proud of how I ran my team, and of what we were able to do against the odds at the drop of a hat.

My original intention had been to create a weekly anthology. Being digital I thought it didn't matter if the comics were 2 pages or 100 long. There weren't the same restrictions as print. I wanted to call the app “Page 1” – as though it was the first of a new kind of delivery system for the medium, literally starting at page one. The thought I had was to have a free – freemium – version supported with ads. The thinking being we could bury the ads amongst the stories, or even in the stories themselves, like product placement, or on huge screens if the story had a kind of Blade Runner-esque setting. These, being digital, could be rented spaces, and the ads could be switched out for new ones. But we could, I thought, also do a paid-for subscription version without ads. I coined the term “the astonishing story engine”, which was the idea – to build a place where creators could share their IP in an environment with ties to movie studios, etc.

Sadly most of that wasn't how it played out. The problem with start-ups, where investors have the majority shares, is that you are at the whim of the board - which I wasn't officially on either, though I attended the meetings. Madefire became less about developing IP, and more about being a service – creating Motion Book apps for other publishers, or as a lab developing 3D storytelling concepts for third parties. I got hugely depressed and disheartened, and felt everything from my original dream had been lost, so I eventually left around 2014 – which is when I got the Wonder Woman opportunity.

Well because it needs to be said, you made some gorgeous work at Madefire like Cap Stone and Sherlock Holmes. Besides working with Bill Sienkiewicz, why did you want to make a Holmes story?

I'm definitely proud of that work. I was pushing myself hard there. The Holmes story came about because I wanted to demonstrate that we could do illustrated prose on the app too, which I thought might broaden its appeal and bring in a different audience. The material had moved into public domain, and Bill seemed – and indeed, was – a perfect collaborator. Working with him is what dreams are made of. It was a complete joy.

Cap Stone was a great book, and this was a book that you and your wife made together. How did the two of you collaborate?

My wife, Christina, has always been a great test-bed for new ideas, and she's amazing at helping me form concepts and stories. For Cap, though, we worked to develop it together. I'm still incredibly proud of it. Artistically I wanted to do the kind of book I've always dreamed of – something more like an Alan Moore, Bill Sienkiewicz project, that paid homage to the comics I loved from the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. It was created to work digital-first in the Madefire app. I had to reconstruct it for print later, for the Titan series and collected edition.

On the one hand Cap Stone is crazy and it's this very expansive story, and it really feels like a book that had been percolating and building over years. It’s hard to sum up easily, but it was a really impressive comic.

Thank you! It's a slow burn, but it covers the kind of territory that those great deconstructive titles did a few decades ago – the notion of what a real hero might look like, and how that might play out in the media, etc. It's as much a sci-fi story as anything else behind the pink mask though. And it's also a mystery – Charlie Chance, Cap's sister, is trying to find out where Cap has gone, and what happened. Lots of very flawed characters, and – I hope – human reactions to extraordinary events. There’s also a lot of allegory in there too. It comments on mass media, fear and paranoia.

I just wish more people had read it!

When Madefire dissolved we lost our ownership of the title, which is heartbreaking. I hope in time we can find a way to get it back somehow.

Cap Stone definitely fits in with a lot of rethinking superhero stories of the 80s and 90s, and makes me think of a lot of writers and painters and clearly that period and a lot of those works have continued to inspire you.

They have, yes. I think they always will!

Now in hunting around the internet to learn more about you, I came across something called Beardism, which despite being a bearded man, I know nothing about. What is it and how are you associated with it?

Ha! Beardism as an art movement was coined by an artist friend called Beth Heany, who was curating shows around Derby. The idea kind of lodged with me, and I started producing work that presented itself as a lost art movement born in Derbyshire back in the 60's, along with other local creators like tattooist Adam Dutton, and local renaissance man, Ali Powers. I wrote a series of poems, missives, and faux-histories, and eventually I found I had – without even really realizing it – written a novel, Andrew Wilmingot's Paradise Rex Press, Inc. I sent it to my friend, the incredible China Mieville – an astonishing writer of science fiction and fantasy, and one of the great “new weird” writers, alongside M. John Harrison, Neil Gaiman and others. I had no idea what it was, other than a postmodernist, experimental, deeply personal, meta-self-portrait in word form. China wrote back saying "I love, love, love this!", and called me down to London to talk about it.

For some reason that day I became incredibly sick, running a crazy temperature and feeling horribly nauseous, but I wasn't going to miss meeting up with one of my all-time favorite authors to talk about my own book! I managed to keep it together over the two or three hours where he went through the entire thing with me, sharing notes and thoughts. The train ride home was hell, and the second I got inside our house I exploded! It was messy! I was in bed the next few days, but I was also elated. China agreed to write me an afterword, which he did – and it's amazing. The book was published by PS Publishing around six years ago, and China honored me even more by picking it as one of his five recommended books when he was asked to guest curate the reading group list for the Royal Society of Literature. That's as high an accolade as I think I've ever had in many ways. Humbling and still incredible.

What was it about Wonder Woman that appealed to you?

I'd heard through a mutual friend that Frank Cho had turned Wonder Woman down, which surprised me. I later asked Frank if that had been true, and he said no, but either way – that was what put Diana in my head! When I got home that night I went to turn off my computer, which at the time had a very elaborate Red Sonja piece I had done as the screensaver. It's a really Barry Windsor Smith homage, and I suddenly thought – hang on. You could do Wonder Woman like that! Lean into the fantasy, and the symbolism, and detail. That night I had a massive Wonder Woman dream – which I later kind of drew in my short Wonder Woman story “The Prophet” – and I woke up thinking I need to pitch this. I never have dreams like that, so something is telling me to do it!

I sent Jim Lee the Red Sonja piece, saying “Hey, Jim. You could do Wonder Woman like this.” He immediately texted me back, saying – hell, yes you could! And he asked if I'd ever drawn her before. I replied that I hadn't, but would do a test piece right away – and that became the tryptic that ended up in “Love is Love,” and that ultimately got me the job. I was tied to the title before Greg [Rucka] was even involved, and initially started developing it as the lead artist with a completely different writer and editorial team. It took quite a few months before Greg came onboard, but I think it worked out well for all of us in the end!

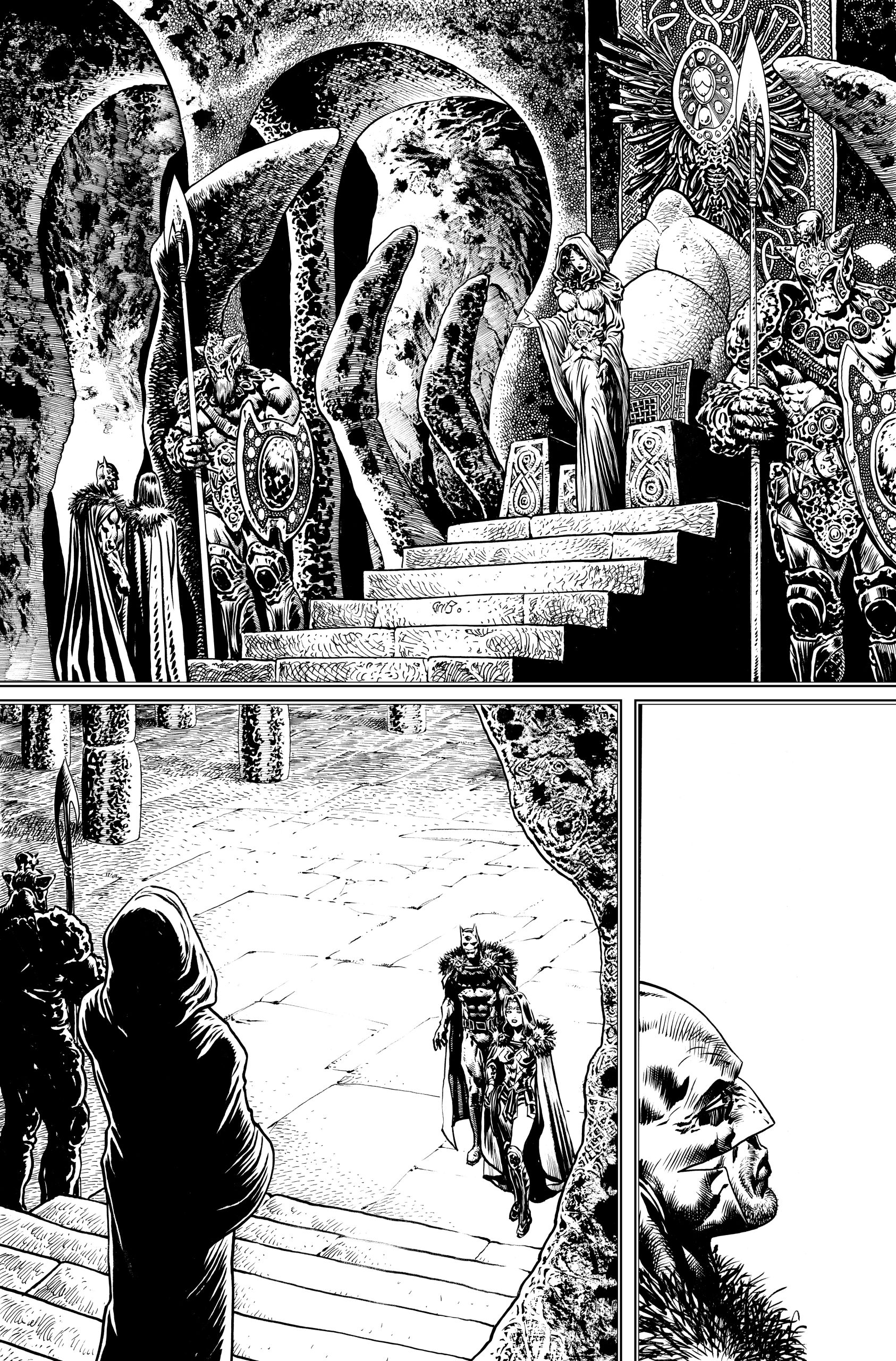

After your run on Wonder Woman wrapped, did it take a lot of work to get to write and draw The Brave and the Bold?

Not really. Greg was beat after writing 25 issues in a year, and he wanted to concentrate on his creator-owned work – which obviously proved a good decision for him! I wasn't quite ready to say goodbye to Diana yet, so the editor encouraged me to pitch a story.

I wrote it to directly follow-on from our series, and I tried to make it very much the same Diana that Greg, Nicola, Bilquis and I had developed. I wanted her to have the same “voice” and spirit, you know? That was the Diana I'd grown to love. And amazingly DC went for it – Irish and Celtic mythology and all! It was amazing! That material was a long time coming from me – very much a dream project. I've always loved that subject matter.

The Brave and The Bold feels of a piece with your run with Greg Rucka, but talk a little about the art, especially the creatures and backgrounds, because it does have its own approach. And making it look/feel Celtic and differentiating it from the Greco-Roman myth that Diana is associated with.

I definitely leaned into the Celtic folklore and design aesthetic! But I think I was also wanting to try and capture something I loved in the work of Barry Windsor Smith - the way he will move a character through a scene using the panels borders, and certainly his detailed rendering of mythic landscapes. And I loved the idea of playing with folk traditions – for instance, the faeries were meant to have become smaller and smaller as Christianity took hold in the 5th Century, eventually choosing to disappear into Tir Na Nog. I loved the idea that this was just period propaganda, and that the old gods were in fact STILL giants in stature. The same with Balor of The Evil Eye, who is usually portrayed as monstrous looking.

It came together so organically. And it was a proper detective story too. Batman can't fight these magical giants, but he can figure out what actually happened - which is very much not what it appears to be. It was great fun creating this mystery based on ancient myths. I owe a lot to Jim Fitzpatrick, whose book The Silver Arm heavily informed and inspired my story. I was delighted that he wrote an introduction for the hard back! I did also want to try something I had dreamed of doing forever, and make a section of a comic a travelog – literally a journey around the world you've created. And I loved it! I wish I could have expanded that and made it even more of a voyage of discovery around all the wonderful magic realm that these legendary beings inhabited. I tried to give the characters a much more earthy vernacular too, as Greek, Roman and Amazonian can be rather lofty!

Diana is able to be part superhero, part myth, and cross into a few different genres, and Green Lantern similarly can play around with a lot of ideas and approaches.

I think you're spot on. It's one of the things that makes Diana such a fascinating character. She's part goddess, part ambassador, part superhero. She's not, however, a detective – which is why she needed Bruce. And that's definitely part of the appeal of Green Lantern – as Grant [Morrison] said, he's not really a superhero. He's a policeman. He works within a system, but he's a maverick, and the system is galaxy-size – and bigger even. There's a lot of room for out-of-the-box thinking!

After writing and drawing a book, why did you want to draw Green Lantern? Were you a fan? Was it working with Grant Morrison?

Grant and I had been increasingly drawn into each other's orbits, and we kept meeting at events at greater and greater frequency. Of course I was a huge fan from way back, and we started talking about doing something together. When Dan Didio phoned and asked it I wanted to do Green Lantern with them, it was a complete no-brainer. The fight I had was convincing them I could do two straight seasons of 12 issues each with no fill-ins. They really didn't believe anybody could do that any more, especially not in the timeframe! But I said that was a deal-breaker if not, so they relented and we went for it. It proved to be a truly wonderful experience. We were kind of made for each other it turned out.

Why was drawing the book solo such a dealbreaker for you?

It was really to do with keeping a sustained, unique vision from two creators. We wanted it to be “our” book.

With the best will in the world, when another creator comes in they generally have very little intention of trying to stay true to the look and feel of what has gone before - understandably they want to impose their own imagination on the book, their own creative sense of what it should be. Grant and I wanted to make it consistent, so you knew you were coming back to the same two creators every month.

But I also knew I could do it, and wanted to prove that. It was a bit of a pride thing – and if I’m honest, there was a little bit of me still trying to show any ancient naysayers (and also myself) that they were wrong to doubt me. It was, I think, something I HAD to do, as an act of catharsis.

And also, people crave the consistency of a tight, dedicated and singular team in comics – which is harder now because comic art has become a lot more complex generally. I say it often, but comics are extreme-art – the hardest form of art to produce that I know.

It’s a marathon that can last years.

I think I've written this before, but I find Green Lantern a deeply goofy concept, but I've read a lot of Green Lantern comics because it's a book that is so defined by its artists. Rereading yours and Grant's run, I kept thinking about how it really can be a showcase for artists to have fun. As you did in many different ways throughout the run.

It IS goofy, but that's the fun of it! There's nothing else really like it. I did always love the costume, and I'm a big sci-fi and fantasy fan. I adored Starlord back in the day, by Claremont and Byrne, and we saw it as a chance to explore all our childhood nerdiness – from 2000 AD, through Heavy Metal Magazine, to the general goofiness that is a lot of mainstream US comics. It was a curious hybrid of everything, and each issue presented fantastic opportunities to explore not just space and time, but the medium of comics itself. I think I'm still in denial that it's all over!

You really went all out in different ways. Those first few issues I know blew away a lot of people with all the characters and details you drew and then you were coloring and painting later issues. The two of you were always playing with what you could do, story wise and design wise.

Part of the notion was to take readers not just through time and space, but also through the medium of comics. If you could have F Sharp Bell in a lightless universe, and Green Lantern viruses, Green Lantern planets, or robot suns, then you could also have the Green Lanterns of comics, and explore that as a 2D space of great richness and variety. And it's also a journey through the second great phase of Green Lantern lore, from John Broome onwards. The first issue is very traditional in approach. The final issues were intentionally done as a kind of homage to Grant's book with Dave McKean, Arkham Asylum, and then – as Grant noted – beyond into something uniquely our own. It tied a knot in their legendary time in mainstream comics, which – currently, and pointedly – ended with our run.

You and Grant seemed to work together very closely and really trust each other. More so than a lot of collaborations.