I blame The Comics Journal. And you, its readers.

What started out as a pop culture detour turned into a rabbit hole, as I was doing research for my 2016 book Hidden Hemingway. As part of that project, I began collecting Hemingway references in pop culture, including a growing list of appearances in comic books. That research turned into several articles for The Comics Journal and reader feedback helped me find even more Hemingway guest spots in comics.

That detective work is now the 300-page book Hemingway in Comics, out this month, in which I’ve explored more than 120 Hemingway appearances, adaptations, homages, and doppelgängers from across the 18 countries. In the last 100 years of comic art, Hemingway has appeared alongside Wolverine, Superman, Mickey Mouse, Lobo, Jenny Sparks and Captain Marvel, just to name a few. The book features the work of creators such as Charles Schulz, Garry Trudeau, Colleen Doran, Cliff Chiang, Paul Pope, Sophie Campbell, Frank Miller and dozens more.

And it makes sense.

Comic book creators and Hemingway share a natural kinship. The comic book page demands an economy of words, and—for multi-panel stories— a lot of the action takes place between the panels. It’s an interactive reading experience, much like Hemingway’s work. It demands that you interpret and bring yourself to the text.

As Brian Azzarello wrote in his foreword for Hemingway in Comics, “You, the reader, are part of the language of comics. You have to fill in a lot of blanks, and the space between panels. These are static images that really move when you’re inside the story and things start to pick up speed. Through Hemingway, I learned to celebrate weakness in my characters...Hemingway’s characters have rich inner lives, so their actions have meaning. Even if you’re not getting into their heads, their words and actions tell you who they are.”

I found a curiosity among comic creators about Hemingway and how his legend gets recorded, distorted, parodied, and boiled down to its essential parts. Hemingway has turned out to be the perfect avatar for comic book artists and writers wanting to tell history-rich stories. He passed through the most beautiful places during the most chaotic times: Paris in the 1920s, Spain during the Spanish Civil War, Cuba on the brink of revolution, France in World War I and in World War II just after the Allies landed in Normandy. He is a fixed point and iconic touchstone that comic book creators love to invent stories around. Even when he’s not the center of the book, a cameo appearance injects the story with energy and pathos.

Below, just few brief excerpts from Hemingway in Comics:

Superman #277 (1974)

Writer Elliot S! Maggin has fun with a Norman Mailer / Ernest Hemingway mash-up character dubbed Ted “Pappy” Mailerway, a reporter-turned-hunter and a temperamental man of adventure.

“At the time I wrote that story I was going through a long-term Hemingway jag. And my friend Denny O’Neil was doing a similar Mailer binge. I had always thought of Mailer as a kind of rogue not quite worthy of Hemingway-esque hero worship. I thought of Hemingway as a more productive rogue,” Maggin said.

He continued: “I had a professor who was a friend of Mailer and that made him seem a much smaller figure to me, I guess. But I had a lot of respect for Denny’s perceptiveness, so I was re-evaluating Mailer in my mind and ended up merging him with Hemingway for that character. Maybe I was just sucking up to Denny. Who knows?”

In the story, Mailerway is a reporter at the Daily Planet, before the arrival of Clark Kent. He also put the moves on Lois Lane, and in one flashback panel, he embraces her from behind and suggests they cover a story together abroad. “N-no, thanks, Mr. Mailerway! I’m just a city girl!” she tells him.

Curt Swan provided pencils on “The Biggest Game in Town!” in which Mailerway hunts the biggest game in Metropolis: Superman. He doesn’t want to kill the Man of Steel, mind you, just prove that he’s Clark Kent. In the end, Superman outwits Mailerway, who still has his doubts about the last son of Krypton’s secret identity.

Hemingway Comix (2008)

At one point in his life, benjamin sTone couldn’t get enough Hemingway.

“I devoured everything I could in junior high, although I enjoyed reading about war and picnics more than bullfights. My grandmother assured me it was ‘a phase’ that every man who reads goes through,” sTone remembers.

“While not entirely without merit, she chased her comment with a crack about no matter how much ‘pain’ he was in, ‘He took the coward’s way out.’ As a kid already struggling with mental health issues, it oddly made me read more deeply into it,” he says.

In college, sTone majored in English “and took a solid 300-level course about his work, which helped me decide which bits of his work to take and which to leave. The Sun Also Rises was beautifully written, yet stirred me little, whereas I’ve probably read A Moveable Feast four times, at least. I liked For Whom the Bell Tolls but took a pass on The Old Man and the Sea.”

“I’m an emotion-based person, and never identified as particularly masculine—these days I get to use the word genderqueer—and looking back, that definitely colored which of his works I still recall fondly and will occasionally reread,” sTone says.

He explains: “He was a macho motherfucker who was somehow startlingly in touch with his emotions. I just sobbed for ages when I finished A Farewell to Arms, and wondered how somebody who could write about sadness so beautifully would want to go out and do something like shoot a goddamn elephant,” sTone says. “I have a bit of a complex response to him.”

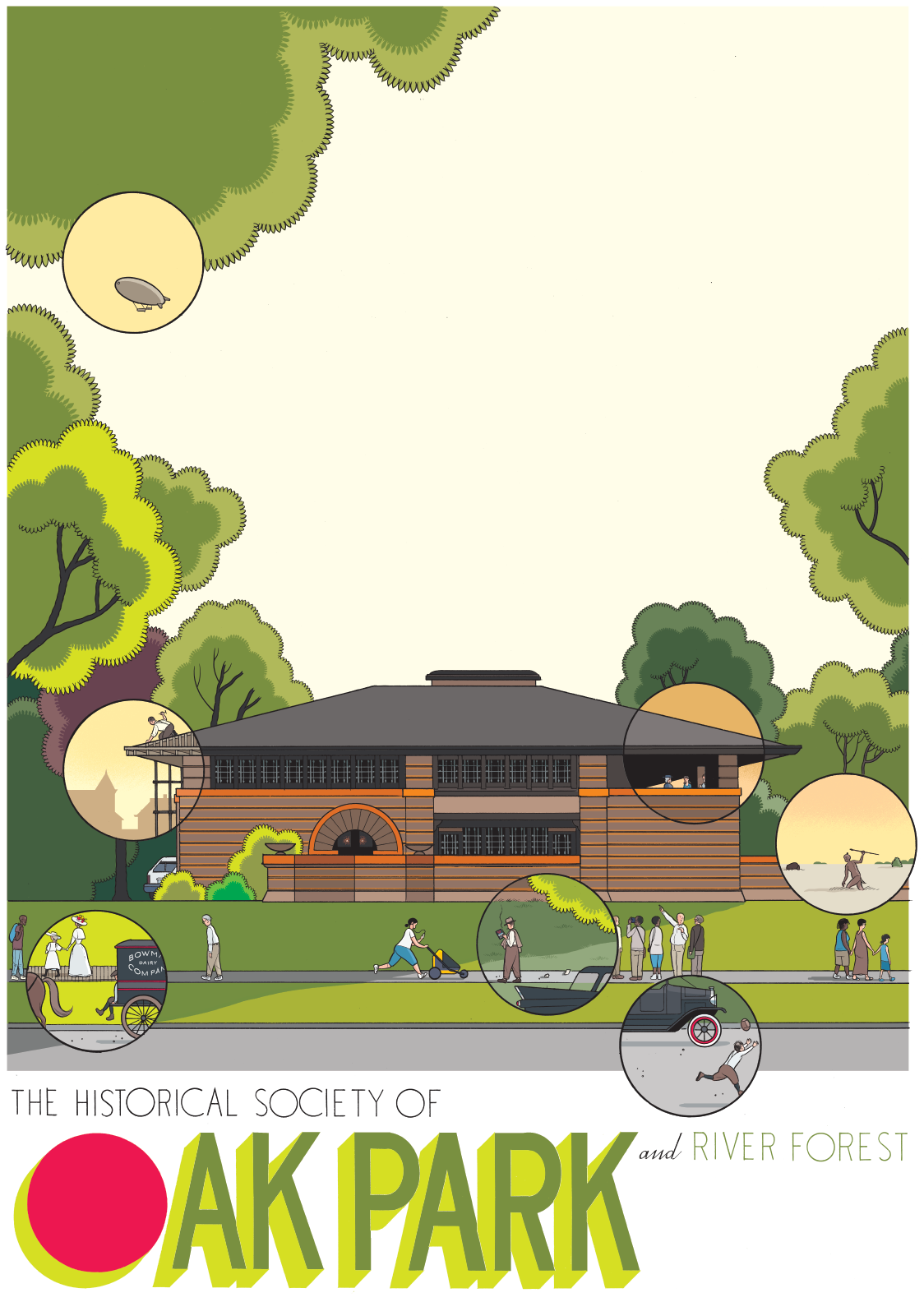

Historical Society of Oak Park and River Forest prints by Chris Ware (2012)

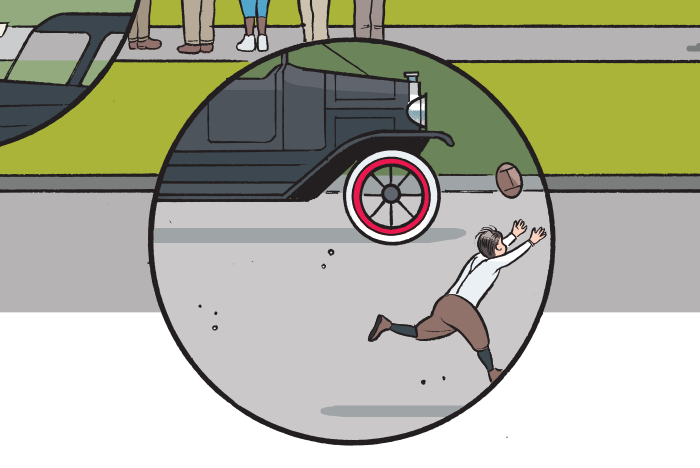

If you blink, you’ll miss him. But the young Hemingway is there, in his hometown of Oak Park, playing football in the street in front of the Frank Lloyd Wright–designed Arthur B. Heurtley House (1902).

Ware, best known for his New Yorker covers and books such as Building Stories (2012) and Rusty Brown (2019), also lives in Hemingway’s hometown of Oak Park, Illinois. Ware designed this print and two others for the Oak Park River Forest Museum, as part of a fundraiser.

“I included Hemingway because he’s, needless to say, an important figure in the town’s history, and, well—how couldn’t I?” says Ware. “I read For Whom the Bell Tolls and The Sun Also Rises in high school and it was the first time I realized that writing could be writing and not just storytelling; I was struck even then at how Hemingway carefully tuned the order of sense perceptions and experiences directly to how one would experience them. If that makes any sense. In other words, it felt real.”

Inspired by Richard McGuire’s comic strip Here—which uses embedded frames as windows into other time periods, Ware’s prints also capitalize on his love of architecture and his layered, Easter egg–filled storytelling. In another image for this series (not included here), an unidentified pedestrian is reading For Whom the Bell Tolls.

***

Robert K. Elder is the award-winning author of 13 books and the Chief Digital Officer at the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Elder’s work has appeared in The New York Times, The Paris Review, MSNBC.com, The Los Angeles Times, The Boston Globe, Salon.com, The Oregonian and many other publications. You can find him online at robertkelder.com and on Twitter at @hiddenhemingway and @robertkelder.

For more about Hemingway in Comics, visit hemingwayincomics.com or buy it here.