Nine Antico's Paris studio sits off rue Saint Denis which, for centuries, has been a red-light district. Its rag-trade sweatshops alternate with peep shows and the corners are punctuated by women in towering heels. To reach Antico's workplace you travel down a dim passage, cross a tiny court, and take five flights of stairs. On the way, you pass a giant sign that reads "POURQUOI PAS NOUS"…WHY NOT US?

Nine Antico's Paris studio sits off rue Saint Denis which, for centuries, has been a red-light district. Its rag-trade sweatshops alternate with peep shows and the corners are punctuated by women in towering heels. To reach Antico's workplace you travel down a dim passage, cross a tiny court, and take five flights of stairs. On the way, you pass a giant sign that reads "POURQUOI PAS NOUS"…WHY NOT US?

Although it's just the name of a ground floor garment factory, this could well serve as the motto for all Antico's heroines. Some of them are preteens who struggle with family expectations and some are coming of age in estates on the edge of Paris. But others are erotic icons plucked from American culture, such as the 1940s fetish pinup Bettie Page, the porno film pioneer Linda "Deep Throat" Lovelace or the told-it-all Sixties groupie Pamela Des Barres.

Working with a novel-like accumulation of detail, Antico tells their stories using cinematic ploys. Her books move via close-ups and long shots, establishing frames and jump cuts. She also plays with narrative structures and often shifts our point of view, pulling back in order to reveal that things were not what they seemed. Although her characters are drawn realistically, sections of their faces, figures or surroundings are missing. She handles everything to do with her art, including the colour, herself.

Antico's Glénat books – which have the pop-tune titles Girls Don't Cry and Tonight – owe a surprising debt to early Disney animation. In visual opposition to her books in black-and-white, these albums privilege colour and contour over psychology. Antico says she likes how the Disney artists "detached" their figures, placing clean depictions against highly rendered backgrounds. "What grabs me is their naïveté. It's a style that reminds you of your fantasies as a little kid".

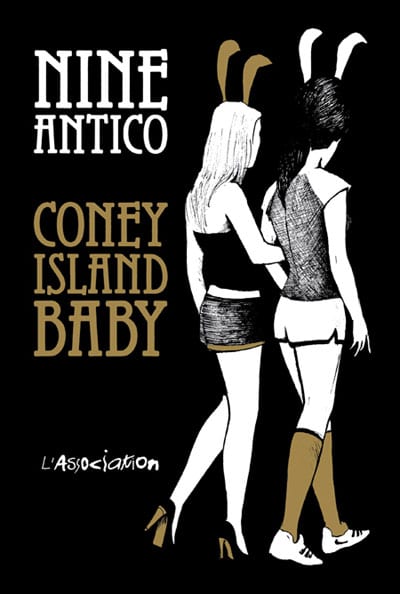

When it comes to Antico's Coney Island Baby, however, little involved in her work is kid-like. Coney Island follows two modern Playboy Bunnies as they try to discover the lives of Bettie Page and Linda Lovelace. While these three sets of destinies collide, the book's monochromatic balance tilts slowly towards the black. Brought out by L'Association in 2010, Blank Slate Books is now issuing an English version.

This month, Antico debuts another ambitious tome, once again published by L'Association. It's called Treat Me Nice and comprises "Side One" of the two-part Autel California. Taking place in the Sixties musical heart of LA, its title (in French, autel means altar) refers to the heroine. A groupie who worships both rock and rock musicians, she is known as "Bouclette" or "Ringlet". Her inspiration was Pamela "I'm With the Band" Des Barres.

This month, Antico debuts another ambitious tome, once again published by L'Association. It's called Treat Me Nice and comprises "Side One" of the two-part Autel California. Taking place in the Sixties musical heart of LA, its title (in French, autel means altar) refers to the heroine. A groupie who worships both rock and rock musicians, she is known as "Bouclette" or "Ringlet". Her inspiration was Pamela "I'm With the Band" Des Barres.

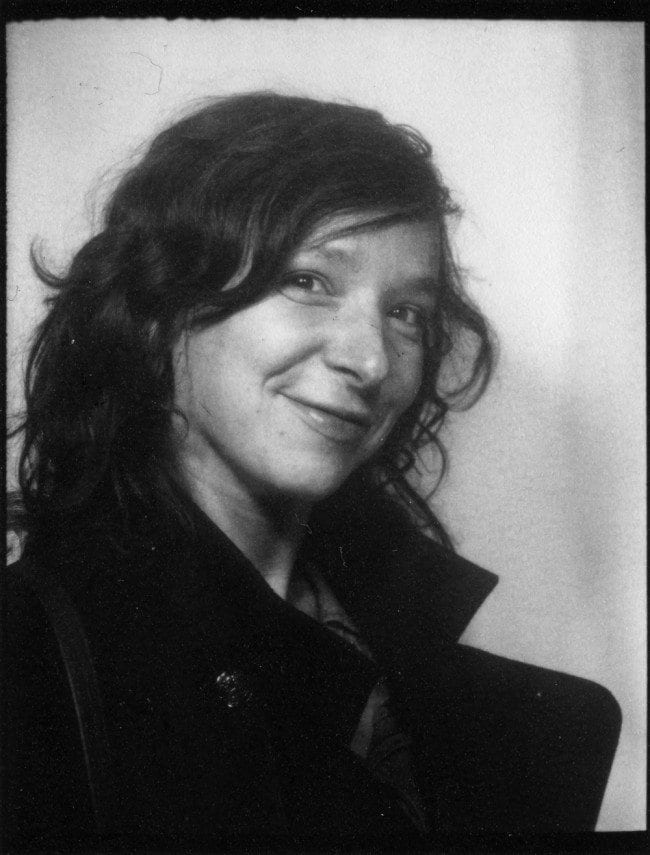

Nine Antico was born in 1981 and she grew up in Aubervilliers, Seine-Saint-Denis. Located north of Paris, this suburb is home to numerous immigrants, government housing projects and the national football stadium. Especially in hip-hop, for which it is also known, the area is frequently called "93" – after the number of its postal suffix.

Seine-Saint-Denis is the banlieue, a very different universe from that of touristic Paris. Although she is far from an ideological artist, its realities have been important to Antico's work. Given its contrast with the bande dessinée's "girly" genre, her feminine universe appears even more singular.

That "girly" universe is a French publishing phenomenon. Its surfeit of cute characters – wry yet always essentially upbeat – first appeared in the country's blogs and women's magazines. Savvy editors turned their arch and lightweight conversations (which centre around relationships, shopping and staying skinny) into a rich new market. It now reaches well beyond the bande dessinée and can be seen in everything from advertising to school supplies.

The founding inspiration for these "girly" girls was Penelope Bagieu. She was the illustrator whose blog – Ma vie est tout à fait fascinante (My Life is Completely Fascinating) – led the way into different media. But Bagieu also created the best-selling Joséphine series. In fact, she followed a shrewd path towards her métier: after the Ecole nationale supérieure des arts décoratifs, Bagieu added time at London's influential Central Saint Martin's.

Nine Antico was rejected three times by art schools. She credits music – not art – for changing her world. "It was thanks to music that I really discovered myself. Not only did it open my mind; it opened doors for me. Music led me into meeting people I would never have known. It was part of my waking up to the world, part of leaving my banlieue."

She ended up by studying, then briefly working in, cinema. But Antico spent more of her young energy trying to learn about music. She devoured Michka Assayas' Dictionnaire du Rock, awed by the "fascinating, troubled lives" in its 3,000 pages. She haunted concerts, started a fanzine and traded her drawings for entry into clubs. Then, in 2009, one of her sketches became a comic.

Called Le Goût de paradis, the book depicts a sentimental education banlieue-style. Drawn with an almost apoplectic expressionism, its characters' conversations reveal an honest and funny ear. At Angoulême, it was a finalist for the Prix de Meilleur Premier Album.

Antico says her attraction to the form came naturally. "From the beginning, it's always been a drawing, a thought and then a phrase. Plus I've always had a thing about cutting out images. At home they cover my walls, because I like their coincidences. Putting them up there just makes things happen between them." For her, juxtaposition is a part of balance… and balance matters a lot. After she finishes every page, Antico holds it up for scrutiny. Before she adds colour, she always checks for equilibrium.

When it comes to storylines, her impulse is similar. "How I work is very precise. When I read about someone's life, I note the decisive moments, all those times it seems like something important is happening. I'll create a chronology of 'importance'. But, when a situation makes me ask myself something, that's where I zero in. Because it's really about some emotion linking me to that person. If you're going to talk about another human, speak as them, you need to understand why they have touched you."

She was struck, for instance, when Bettie Page described her screen test. "Because, in my own life, the same kind of thing has happened. I think it happens to everyone, that moment when you feel everything is about to change. You think, 'OK, after this, doors will open for me'. Then it turns out to be nothing of the sort."

The culture she portrays in Coney Island is American (she took the Lou Reed title to honor the beach where Page was "discovered"). But, although Antico spent four years on research, in the end the work was guided by her instincts. "You don't need to search for some epic way to tell these histories. Because you’re going to there via these tiny things; it's an accumulation of detail which will set the tone. When I'm sensitive to a detail, I always know that there's a reason."

However, there is also a more personal side. "I'm attracted to that whole American thing of je veux, je peux. I want to, I can: that corresponds with my own background and my mentality. It was really American culture which first made me dream."

Even her Glénat books display a female determination. Their characters Julie, Pauline and Marie offer a mordant contrast to all the "girlier" girls. Antico's portrayal of these friends is also less than flattering. But, says the artist, there are important reasons. "I reflect really hard before I try to express those stories. Because there's a certain sadness in what I relate about girls, a certain melancholy inside them that is present in all my stories. The era or the place – even love – can't change that sadness. It's a form of interior struggle, one in which gaiety and melancholy co-exist. What interests me about that are the ambiguities."

Not only has she found the tools to articulate them. As critic Jean-Claude Loiseau has noted, Antico knows how to "separate the light touch from one that is merely superficial." A French blogeuse from Retard magazine puts it differently: "She draws girls like us, superficial and romantic, funny and vulgar, but with strong characters".

All of Antico's art is serious about gender. Yet as a child of the Nineties, she's used to sexual liberation. Like AIDS or contraception, it's just a given. "Of course it's great if now we can sleep with someone we like. But, out of all that individual liberty, what have we made? It opened the doors to good experiences but also to hard ones. How a woman finds her place among all that, it touches me."

Thus her lives of Bettie Page, Pauline and Bouclette pose similar questions. Many of these concern reconciling dreams with independence. "Once you've fallen in love, what really happens to your autonomy? How do you conserve your freedom, how can you preserve your esprit? Take Simone de Beauvoir, when she fell for Nelson Algren, when she was finally face-to-face with love. The pillar of feminism was as weak as anyone else!"

But is Nine Antico more than a comic book Kathy Acker – and do her groupies and bondage queens have anything new to say?

Like Acker, she's fascinated by transgressive icons; their appeal is the same as the "crazy, prolific" lives she loved in the Dictionnaire du Rock. But even as Antico presents their excesses, the real shock comes from her characters' basic normality. Coney Island's fetish photo session takes a break for cookies and Linda Lovelace has fantasies about a microwave. Both as Antico researched it and as she imagines it, life as an icon is frequently mundane.

Her pulp fiction sources yield more than just lewdness or craziness. One of the questions in Autel California, for instance, concerns the things – and people – art always excludes. What happens to the person who is obsessed with music, yet who lacks musical talent? What about those girls the camera doesn't love? Researching in LA, says Antico, helped illuminate that. There, she hung out with numerous Sixties scenesters: all still attending concerts, still saluting the ghost of Gram Parsons, still going to spiritual advisors with names like "Light".

She even attended the writing workshops held by "Miss Pamela". ("That was ten women with nothing in common but music and boys. You're at her house, it's very relaxed, you can ask her anything. It's like a Tupperware party. But then she says, OK, you have fifteen minutes to write a piece on your father!"). In addition to all the concerts and ateliers, however, Antico took note of the day jobs at Goodwill and the AA meetings.

The music, she decided, had papered over enduring disparities. "Pamela has been able to guard her openness. From the very beginning, she had this kind of artless character – and she has it still. But her thing is not at all to look on the dark side, so her books have nothing to say about Manson or Vietnam. I'm different; I want to find my way to the sadder subtexts."

One of the keys to these was Des Barres' lifelong pal "Miss Mercy". A former drug user and upfront bisexual, Mercy's less conventional character had a big effect on the book.

"Unlike Pamela, she was ravaged by that life. Partly, I think, because she’s not from that blonde milieu. The privileges of beauty – they just open so many doors. Yet that's something pretty women never like to talk about. So I'm also trying to speak for those who have passion and personality and feel involved. Yet – maybe they lack attractiveness, maybe they have no creativity."

Both Coney Island Baby and Autel California take place during brief moments of euphoria. Each captures a small world as it passes from amateur status over to something more professional. In the case of Bettie Page, this is photography; for Lovelace, it's underground cinema; for Bouclette, the post-Elvis, post-Beatles music business.

The choices were not accidental. "What intrigues me is how, at moments like those, everything can seem possible. Things start out on this almost familial basis, even things like Bettie's photographic sessions. But, eventually, there's a junction with it becoming an industry. So something that could have stayed small forfeits all its spontaneity and, eventually, it has to become polluted.

Each book charts this territory through its heroines. But the curiosity and the perspective belong to Antico. "I wanted to know how something positive gets infiltrated by its opposite. How the evil – in French, of course that's masculine! – inserts itself. Take the boys who made that Sixties music, the source of so many fantasies. Once Bouclette is really tied to them, what does the story become? Just in terms of 'celebrity', that can still speak to us."

Eighteen months ago Nine Antico made her first short film, a wistful adaptation of a sequence from Tonight. Now, she is shooting a feature film entitled Playlist. Its music – which she describes as "an interior voice" – helps her paint a portrait of Sophie, a thirtyish woman initially from the banlieue. The film follows Sophie as she negotiates two worlds. One is the universe of love, the other, Parisian culture. At the same time, the artist is filming Hit Girls. This is a documentary on female boxing, something the artist has practiced for two years.

None of this means Antico is quitting the bande dessinée. On the contrary, she loves the medium more than ever. "What I relish are all the different kinds of ellipses and movements. There's something about its rhythmic side which also really pleases me; I even love the white space passing between those frames. The image which shows one thing while the text reveals another…For me, all this is what the bédé has to offer."

So it's a form that lets her say anything? "No – you can never say quite what you intend to. There are too many choices to make plus there are always surprises. But, along the way, you find out new things that matter. So you start by saying, 'This is what I'm going to do'. Yet, in the end, you're dealing with something else."

"It's like everything else in life: you're always going to lose something. So the key is learning how to stay very vigilant."

• Autel California will be published 22 October 2014 by L'Association. Translated by Jane Huxtable for Blank Slate Books, the English version of Coney Island Baby will be available in early December.